In Brazil in 2012, on an early tour with his new band the Sensational Space Shifters, Robert Plant spotted some downtime in the schedule. He immediately led them on an intrepid train ride over a mountain range to an utterly isolated town, its houses painted in a patchwork of colours. Huge Brazilian stews were served to them as they sat in blazing midday heat by the massive river running through the town’s heart. “My God,” Plant’s frequent guitarist and travelling companion Justin Adams remembers thinking, “we’re very far from anywhere.”

Like other old hands in Plant’s 21st-century bands, though, Adams wasn’t exactly surprised. There was that time when a Russian gig inspired a detour to a studio Plant suddenly recalled in Tallinn, Estonia. “I think they’d been informed we were coming,” says keyboardist John Baggott, laughing, “but they looked just as surprised that we actually turned up.” Local papers would be flicked through, on tour with the Space Shifters or their predecessors Strange Sensation, and expeditions launched to see gigs by surf guitarist Dick Dale, jazz giant John Coltrane’s great drummer Elvin Jones, or traditional musicians in Morocco.

“If you were to say why has his music stayed fresh, and his band feel like a real band rather than a bunch of hired hands,” Adams considers, “it’s that he’s kept himself uninsulated. He actually gets out there and he does things. He came to Mali with me soon after we met in 2003. Our car broke down in the sand and he was out there pushing, and sleeping with all of us in a tent on the ground. And then in the middle of a tour he drove me down Highway 61 to juke joints he knew in Clarksdale, Mississippi. He showed me amazing things. And all the time we’ve carried that on.

“We’re so lucky, and so stimulated, and that comes into the music. It’s shocking to me that some ‘rock stars’ live the life of hotel rooms and backstage, and they don’t want to go anywhere. It’s just having a curious mind.”

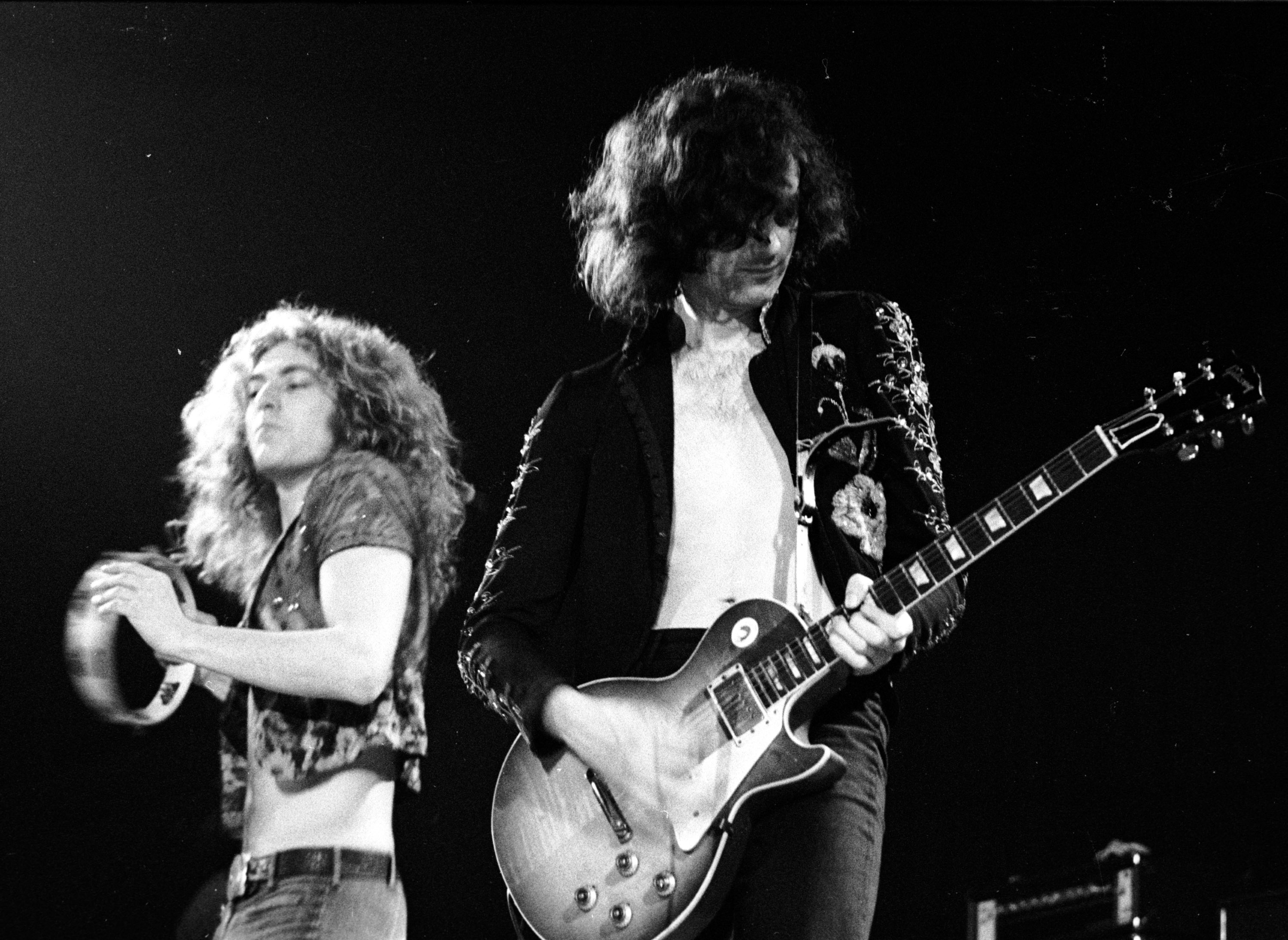

When I suggest to Plant later that his class of rock star usually leads a more protected life, he reacts with distaste. “Well, that’s an affliction,” he says. “I mean, life doesn’t stop because you have a purple patch. The only reason that anything ever happened for me in the first place was because I was in good company. And then, more so or probably equally as much, we adventured, Page and I, with a couple of roadies. We just kept on going and looking. And in the pre-Sahara, or Aberystwyth or Tunis, people don’t care who you are. And I need to be around that feeling. So that I can be counted for my moment in anybody’s life just like anybody else. So I don’t feast with the gods.”

Plant’s wanderlust has today taken him only as far as Whitstable, Kent. He’s driven down from the Black Country to take the sea air with his new girlfriend, in between rehearsals for Later… With Jools Holland at the BBC’s Maidstone studios. Classic Rock finds Plant in a loose casual shirt, leading the Sensational Space Shifters through songs from their new album, Lullaby…And The Ceaseless Roar. They finish with a version of Kashmir very much in that record’s mercurial style, mixing North African and American blues and early rock’n’roll. “Ah, Classic Rock!” Plant booms, bounding over to shake hands.

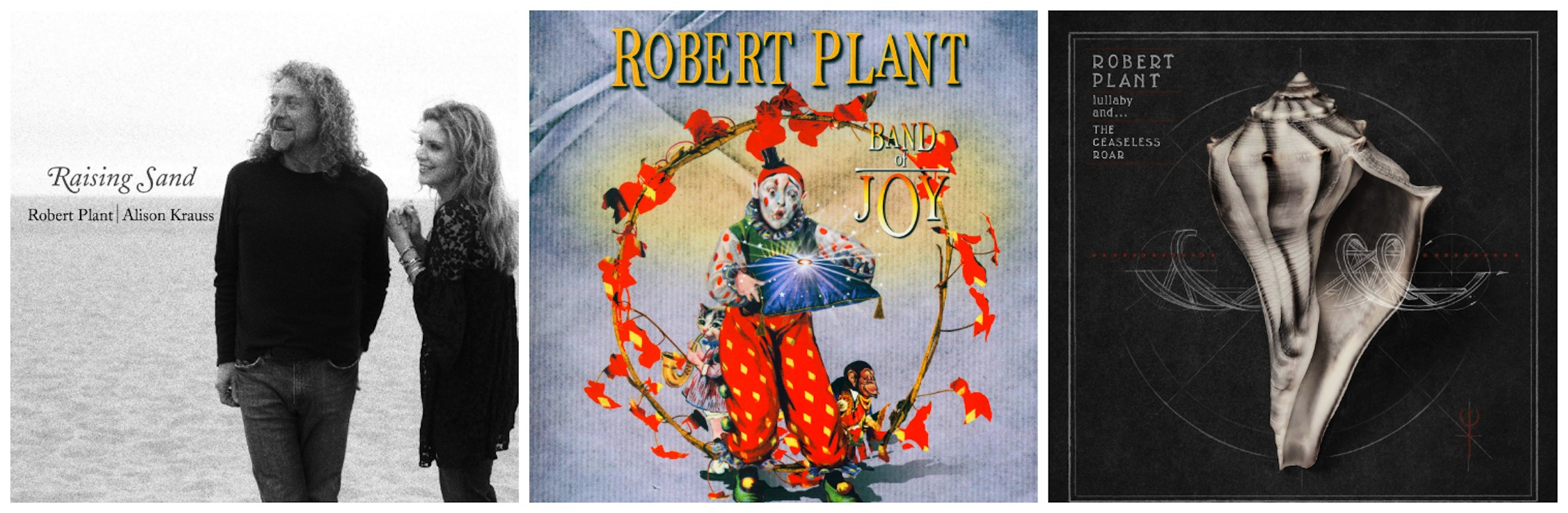

Ever since he passed on the opportunity to repeat old glories after Led Zeppelin’s O2 Arena triumph in 2007, instead pursuing the new ones suggested by Raising Sand, that year’s Grammy-winning album with Alison Krauss, Plant has challenged what ‘classic rock’ can mean. He seemed then to be facing down the myth of his past, preferring a more interesting, wide-open future. As he explains, sitting in a quiet back room, that decision was taken much earlier.

“In the year 2000 I was really looking for clues,” he explains. “Jimmy and I had come to the end of Walking Into Clarksdale’s prolonged exercise of examining the dark interiors of different European basketball stadiums, and the game was up. I couldn’t face it. I didn’t know where I was, who I was or what I was supposed to be. Because we were only giving half of what everybody wanted, and trying to stride forward with new stuff. So I made my farewells and left in peace, and said: now what can I do? And I formed this group called the Priory Of Brion, which was basically going out into the wilderness and jettisoning whatever credibility as a careerist I ever had – with joy. Because finally I had something to do where people would flatly ignore it. I was doing Billy Fury covers in a restaurant in Wales, and my manager at the time kindly said that he would expect no commission, because he was appalled at what I was doing.”

Plant began following a musical trail away from hard rock, focusing instead on the links between his long-time passions of psychedelic and Moroccan music. “I was looking for a guitarist who is not really over-impressed with the work of Otis Rush, because there’s only one Otis Rush – and only one Jimmy Page,” he remembers. “And I was pointed to Justin.”

Justin Adams, who would effectively replace Page at Plant’s side, had just returned from Mali when he got the call. “Previously at sessions, people would be saying: ‘Why are you playing that bloody kebab riff in the middle?’ So I’d pull my North African influences back,” he remembers. “But Robert said: ‘Make it more Shleuh!’ – a Berber tribe from South Morocco. And we had this weird thing where somehow it would make sense to be listening to Howlin’ Wolf or Son House, and to music from Morocco and Northern Mali with the same feeling, and to be equally at home with trip-hop or dub. Which I think was the original approach from Brian Jones and George Harrison when they were hearing things from the Master Musicians of Joujouka or Ravi Shankar – this is just music that takes me somewhere.”

Dreamland (2002), an album of blues and rock covers spiced with pounding, trancy North African rhythms, began Plant and Adams’s collaboration. John Baggott, a keyboard player more used to working with Bristol trip-hop bands, also came on board then. Like Adams, he barely knew who Led Zeppelin were. “Portishead and Massive Attack was more my world. I wasn’t that familiar with what Robert did, so I wasn’t overwhelmed with his status.”

Mighty ReArranger (2005) and Band Of Joy (2010) refined and reworked Plant’s new musical landscape, which is heard at its richest on Lullaby… And The Ceaseless Roar. But it was the huge public acceptance of another covers album, Raising Sand, its quiet Americana songs with Alison Krauss (pictured below with Plant) so different from what Plant was known for, that seemed to be the real watershed in his solo career. Finally he had pulled free of Zeppelin’s gravity.

“That’s your perception of it,” he sniffs. “I mean, The Honeydrippers [a covers project with Page and Jeff Beck], if you go back to 1984, was another huge record. And now I listen to it and I’m not particularly enamoured, because I’ve learned so much more about how to do what I do, and the choice of songs was quite obvious. But I can do that shit. So I was surprised with how Raising Sand was embraced, yes. But it was a very good job done. Mighty ReArranger was for me the first album that I’d written since leaving the 20th century behind. It was Mighty ReArranger that gave me a voice again; Raising Sand was more of a vacation.”

Still, his musical wanderlust this century, splitting bands and moving on after each of his last four albums, gives the perception that Plant is musically fearless. But is that true?

“Oh, I don’t think any of it matters now, does it? Because I’m already typecast in many respects. So if anybody asks you about me, they will go to the immediate Cassell’s Book Of Knowledge or Wikipedia response, which will be: ‘Oh, that’s what he did.’ So no matter what I do, it doesn’t make a blind bit of difference to most people.”

Does having that knowledge cushion him from potential falls?

“No. It doesn’t matter.”

So there’s nothing to fear?

“Well, there should never have been. But success and continuum is a hell of a drug. So some people live and die by it. But I was always looking around. When I was in Morocco in the seventies I was knocking down doors. I just didn’t bring that to the table.”

These days he does. “I’m free to fail,” he says. “I have to make sure I’m a dignified sexagenarian, and carry myself well, but at the same time have a hoot.”

“You stand on the tightrope and you can fall either side,” Baggott says, remembering the Sensational Space Shifters’ first, ragged gigs in 2012. “The fact that you get on the tightrope is what matters. Robert’s not afraid of failure, and he believes in what he does. That comes through on the new album. It’s a true representation of his life, the lyrics are spontaneous and honest. This album’s quite closely related to Mighty ReArranger, but I think this one was much more personal for Robert. It was much more heartfelt.”

“We’ve known each other a long time,” Adams says of the place Plant’s band and its earlier, Strange Sensation version, has in the singer’s life. “Been with each other as parents have died, relationships have succeeded or failed, children been born. That all informs the music. And I think that’s important to Robert. Because it can all turn into an industry, and a job, especially for somebody like Robert, whose name can mean money. And that must feel a bit weird, if you’re him. ‘How can we be anything if every middle-man’s wanting a percentage?’ So it’s probably a challenge for him to create something that’s genuine.”

Plant’s previous album, Band Of Joy, saw him collaborating with a second female country-folk singer, Patti Griffin, whom he tried living with for 18 months in Austin, Texas. That relationship’s collapse is commemorated in several Lullaby tracks. ‘Your heart could not foresee the tangle that I became/That brings me home again,’ he sings in pained apology on Embrace Another Fall.

And now he’s home, back in a Worcestershire village where people know his name very differently from how they do elsewhere. “I was a family man,” he remembers of how he kept these roots even in Zeppelin’s pomp. “I was touring, and then I could come back and have these amazing times, where it wasn’t just my progress that was important, it was the progress of the people that I loved. And one or two of those people stack shelves in Marks and Sparks, and I’ve known those people for a long time. And so why would I ever want not to know them? There’s nothing that changes, really, from the perception that you have when you’re fourteen and you buy your first obscure bit of vinyl from some import shop in Birmingham, and you go to your friend: ‘Wow! Listen to that…’ You join in this communion with people then. And once you’ve cast that die, these times are important forever. So why would you leave them behind?”

He has even broken through the barrier of his stardom to make new friends.

“I didn’t think it was likely,” he says. “You know, you’re very cautious with new people, checking them out, not sure. And then you find, hey, this is great. Somebody’s offering me some new information, some new detail. It’s just carrying on living. I’ve joined the Civic Society near me, too. There’s lots of consciousness that exists just below the high street, down there in the ground, where things still pulse.”

After the great odyssey of his life, starting with Zeppelin’s Viking voyages to America, does he feel like he’s home now?

“I do. We’ve just come back from New York, and in this age of instant gratification, with selfies, and [he makes the chittering sound of the endless clicking mobiles he found pointed at him]… It’s horrific. But of course it’s bound to happen, because I’m quite a well-known guy. But in Worcestershire everybody has humour and a turn of phrase, and because I’ve been around there a long time, there’s no homage. And that’s crucial. Because it means you can’t fuck up. And I can’t keep quiet, but if I start going off the track a bit, somebody goes: ‘Hey! I’m stacking shelves in Marks and Sparks…’”

Plant is still restless, of course. On a recent stopover in Texas he found himself in very rum company when he bumped into the reclusive, visionary film director Terrence Malick (maker of Badlands and The Thin Red Line). Malick invited him on to the set of his latest secretive project.

“What’s his name, Ryan Gosling, was acting with the girl with the dragon tattoo,” Plant recalls airily. “It was about a guy who’s hell-bent on being a hero in entertainment. And Malick said: ‘How’d you feel about him just seeing you, and responding?’ So I ended up in this movie, making my own shit up as I went along. It was so funny. And the next week he asks if he could borrow this old Texas cop car I’d bought, and they lent it to that Welsh guy [Christian Bale]. When the fucking thing came back, to me in my Hippieville world, the rear fender had been cracked. And inside the crack was human hair! He’d driven backwards into one of the fucking film guys!” Plant chortles, delighted. “That was life in Texas: ‘Oh, here’s the car – never mind the human hair…’”

It’s not your usual rock star life. And Plant’s recent run of albums haven’t been the usual music of a coasting veteran from rock’s founding elite. So who does he think his peers are now? Which musicians does he still feel connected to?

“People who push,” he says after a long, thoughtful pause. “If they push with real largesse, and real intent, to me that’s what it’s all about. Somebody like Scott Walker, when he did Tilt [a musically forbidding, semi-industrial album from 1995], I thought it was such an amazing departure from doing the songs of Jacques Brel, or his stuff with the Walker Brothers in the sixties. And Mark Hollis from Talk Talk. And in my spirit I carry a light for Peter Gabriel. He represents our illness very well. I’m not tottering towards people who stay in the same mould. But at the same time, quality is quality. So I’m very interested in seeing what happened to some of those great British singers.

“I know Eric Burdon appears every now and again, and he’s still got the light. And I feel that somebody like McCartney, he’s always trying new shit. And he’s strong and committed about it. But, whether people like it or not, we all get pushed into the funnel and surrounded in crazy foam, and come out into the fucking pool from Cocoon 3. And that is something that none of us want.

“I’d love to go and see The Who,” Plant continues. “I’d love to go and see Roger. I always feel affinity for singers; how are they getting on? You know, when we [Zeppelin] played the O2, it was a tough call to sing those songs. And I think about singers being left with something that they did in their youth, to trade on it most of the time… I hope to see Roger on this current tour.”

Plant has been talking about how he’s free to fail these days, how nothing he does really matters that much in the shadow of Zeppelin. Is singing with Zeppelin, then, the one time when he is afraid to fail?

“Well, yeah. But it would have been right whichever way it went. And we did some fucking horrendous reunions before that. Live Aid was dreadful. And the Atlantic fortieth was no better. It’s just these moments where you don’t have the gift. Like Live Aid – I’d done four or five shows before that. But to go out there and be everything everybody wants for that period of time. I knew that… there was no way of making it any different to what it was.”

Is the relief of his musical life away from Zeppelin that he can be who he wants to be, away from everyone’s expectations?

“No. I can be whoever I am, wherever I am, anyway. Like, my voice is fucked now from rehearsing, but it’ll be alright tomorrow. And if it ain’t, it ain’t.”

The interview is just about over. In a few minutes I’ll see Robert Plant outside, his long curls hidden in a ponytail, suede jacket on against the cold air. Before that, his manager, Nicola, enters the room. I knew her a dozen years ago, when she managed Kelly Joe Phelps, an obscure but grittily fine blues singer-songwriter. The sort of person, maybe, who Robert Plant would sometimes like to be.

“I used to have big-time management,” he reminisces, greeting Nicola fondly. “But they want you to do obvious things. And when you do obvious things, that’s when the illness starts. You start doing obvious things and people around you start smelling opportunities for other things. That’s the distortion.

“So by being here,” he says, looking around with relief, “in this cute little moment, we’re safe. It’s not even the eye of the storm, really. Perhaps the storm’s long gone, and we’re just the bric-a-brac, left hanging on the tree.”

He wanders over to laugh with his driver about Wolves, the team he supports, and disappears.