My ultimate rock icon? Jimi Hendrix. Band of Gypsys was the cornerstone of me making the decision to become a musician. I was eight-years-old living in Washington, D.C. with my mother. We had this little apartment over the southwest and my cousin Donald moved in with us. He was living in a different part of the city and he was trying to escape a bad home life, and he brought his record collection with him under his arm. He was ten years older than me, so he was 18 and I was eight, and he didn’t bring many records but the ones he did bring were all these titanic releases. And the one that ended up being the pivotal one for me was Band of Gypsys.

His albums were very much misused and abused, so the cover was long gone, but Donald had taken a piece of paper and hand drawn this really cool psychedelic picture. The record itself was warped as hell and you had to set a coin on the needle in order to play it on my little Sears stereo system. But that was the one, man. We played that record nonstop for about two years straight.

- How Black Flag changed my life, by William DuVall

- Inside Jimi Hendrix’s first ever live gig

- Hendrix: The Gigs That Changed History – #8 Woodstock

- Objects Of Desire: The Fender Jimi Hendrix Stratocaster

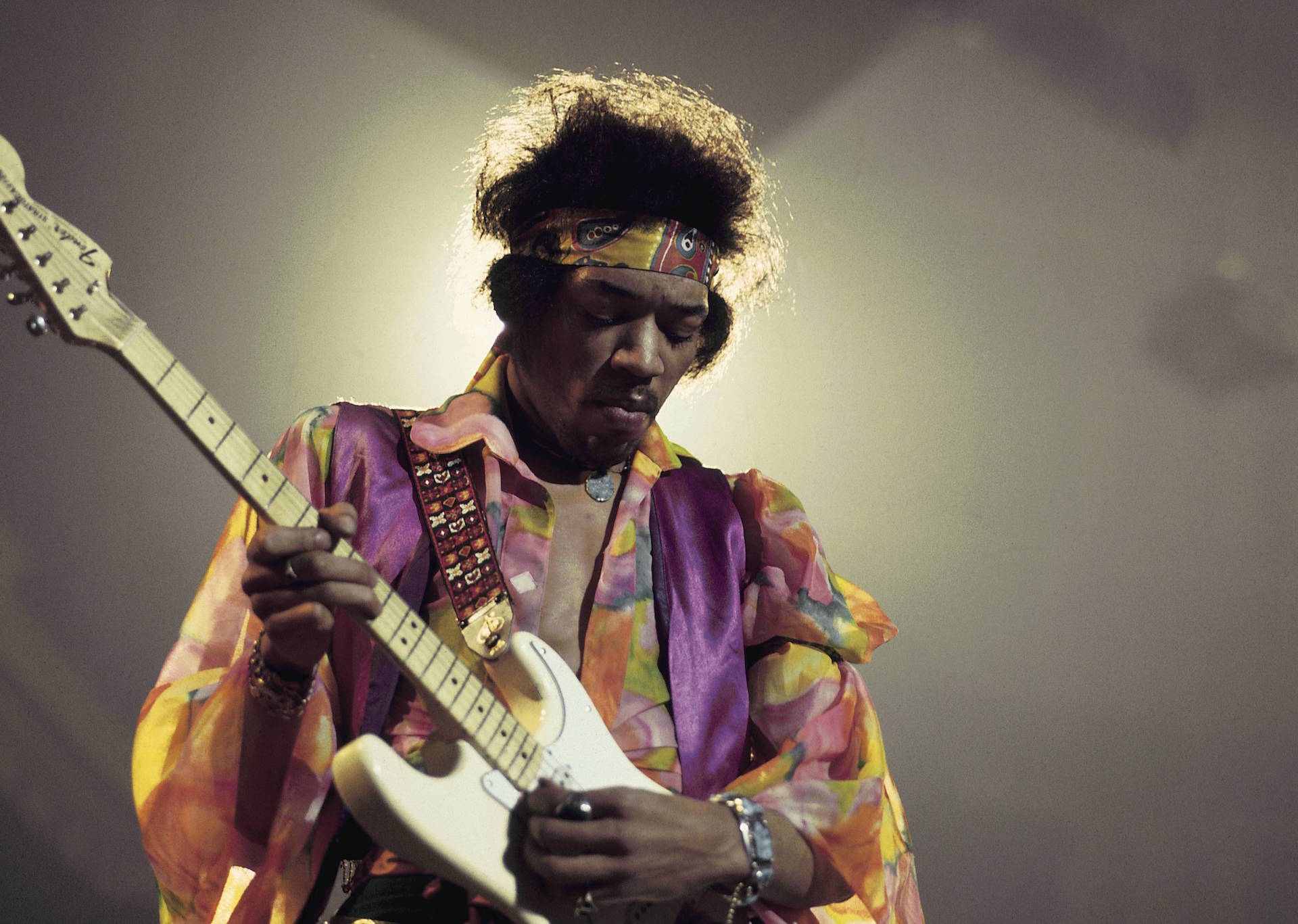

The more I became intrigued by the album the more I wanted to know who was making all that noise. My cousin explained to me that it was this guy Jimi Hendrix, that he’d died a few years ago, and that he made all those noises with a guitar. I was like, “a guitar?” I had no idea what he looked like or anything, so Donald went to the library – because this was 1976 – and photocopied some issues of Rolling Stone with Hendrix in so that he could bring them home to show me. And then I was like, “he looks like us.” It was one huge epiphany after another.

Like I said, I listened to the album every day for about two years. I can still scat sing all the solos on it. Now I can actually play some of them, too. The other thing that was really good, and I consider myself really fortunate in that sense, was my cousin Donald was a great listener. He was really good at pointing out certain phrases and playing them again. So I got to hear all the messages in the notes. It wasn’t anybody singing anything; there were no lyrics or words involved.

I still think Machine Gun is the greatest example ever of improvisation on the guitar. I don’t think there’s ever going to be anybody better than Jimi Hendrix. He completely creates the war in Vietnam right there on stage and in the grooves of the record, and you get it all: you get the napalm bombings and the screaming of the villages, you get the machine gun fire and the grief of the families, you get the whole thing. You also get the conflict of the American soldiers sent over there to fight.

It’s one thing when you’re eight-years-old and you’re just listening to it as music, especially on this warped record, which meant that I couldn’t really understand the introductions between songs. But it’s also a record that can grow with you throughout your life because it’s so high level musically, and yet so basic as well. The humanity of it is so basic. But then there’s also all this really complex noise. He takes it into the avant-garde. There’s a lot of soul on the record, and a lot of touchstones that are both down to earth and out of space, at the same time.

I can’t think of another musician – let alone a popular musician – who’s been able to create that level of range whilst being so cutting edge. There have been a lot of great entertainers who had great range and did a lot of great things to pull people together, like Ray Charles and Sammy Davis Jr. But Hendrix was like an alien. Part of his timeless appeal is that he almost still sounds from the future, even 40 years after his death. His music reflects that. I can’t think of anybody else where it’s quite like that. Even Prince, and him dying was a huge loss for me, was a little different. He had a long and storied career; it was the greatest career I’ve witnessed in my lifetime. But what Hendrix did in just four years, from when he landed in London in September ’66 to when he died in London in September 1970, was on another level.

As great as the studio albums are – and they are great and totally important to me – Band of Gypsys was my whole way in, and I still haven’t heard anything like it in terms of improvisation on the guitar, or even any instrument. You’d be hard pressed to find any instrumentalist who hit it that hard out of the park. And later as I got older and I got cleaner copies of the record I started to hear stuff that I’d never heard before, including the bits in between the songs, like when he dedicates Machine Gun to all the soldiers fighting in Vietnam and Chicago. He was talking about the Chicago Seven, and that made me read up on my history about what was going on with the Black Panthers, anti-war activists and the student movement. Hendrix was a lightning rod for so many things that were going on in his time, and the struggles of what he was dealing with are still so prevalent today.

To think that he could channel the huge dimensions of those struggles through his instrument and through primitive equipment is unbelievable. It’s unbelievable. I’m still spellbound by that record, especially Machine Gun. I still listen to that song and go, “How the hell is he doing that?” There’s footage of him playing the song and he’s standing stock-still. He finds the perfect spot on the stage to stand – because you’re dealing with overtone and acoustics – and he doesn’t move an inch. If you watch him whilst he’s playing that solo, it’s ninja level guitar playing. There’s not one wasted bit of motion, not one false eye blink. He just controls his breathing and rides the wave. It’s unbelievable. There’ll never be another Jimi Hendrix.

Giraffe Tongue Orchestra’s Broken Lines will be released on September 23 through Party Smasher Inc.