For the last twelve years of her life, Tina Bell lived in a low-income apartment in Las Vegas. By then she was effectively a hermit. A church singer who became a rock star, before turning her back on the world.

The apartment was a compact one-bed with a radio, an old sofa and a TV, through which she played music via a DVD player. One wall was decorated year-round with holiday cards. By the kitchen stood a small platform full of Barbie dolls, one with a tiny leather jacket, beer and cigarette: a punk-rock Barbie.

At the centre of it all sat Bell herself, cigarette in hand, nursing “some shitty alcohol” and poring over astrology charts, perhaps trying to find her place in a universe that had all but spat her out. Her son came to visit. Her former bassist brought groceries. Her relationship with her ex-husband – Tommy Martin, Bam Bam’s co-founder/guitarist and father of her child – remained complicated.

It was estimated that she’d been dead for a couple of weeks by the time she was found. The building’s management promptly threw out her belongings, her writings, her music. Her last traces vanished. Even her Wikipedia page was deleted due to a reported “lack of resources”.

In recent years, fuelled at least in part by the Black Lives Matter movement, Bell’s name began to resurface. Online articles were published, shining a spotlight on Bam Bam – these hugely overlooked grunge predecessors, and their singer who looked so unlike other punk and rock singers.

“To the credit of this younger generation, there’s a desire to see people of colour in non-stereotypical spaces,” says Bell and Martin’s son, Oscar-winning filmmaker TJ Martin. “But the reality is there are multiple artists that are navigating spaces that are dominated by an ethnicity not like their own, or that are dominated by men, and as a result you slip through the cracks.”

Tina Bell has been called ‘the queen of grunge’. It’s a catchy, well-meaning tagline, albeit a slightly reductive one, confining a life and its ripples to a soundbite. It’s also rather glib from a musical standpoint. True, a spin of Free Fall From Space (a digital collection of Bam Bam’s 1984 recordings, released in 2019) does reveal something of the dark, sludgy-but-smoky ambience that later typified the likes of Alice In Chains and Soundgarden. ‘Proto-grunge’ would be a fair descriptor.

But that’s not where it ends. Blending moody atmosphere with raw energy, these tracks reflect influences that span the Dead Kennedys, The Doors, Patti Smith, Bad Brains, Aretha Franklin, early Blue Öyster Cult, Johnny Cash and even Frank Sinatra. Not to mention Bell’s early training as a church singer, which enabled her to project soulfully through the noise that rained over her. And she channelled her experience into her lyrics, unafraid to go to some gnarly places. For the jagged, haunting Ground Zero, the band snuck onto a military base to shoot the video (armed guards chased them out).

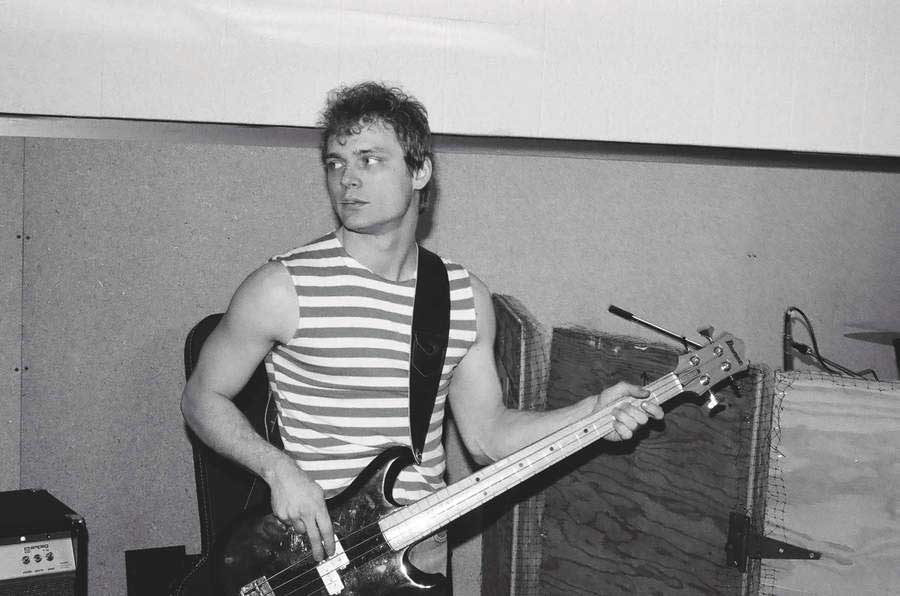

“Bam Bam was schizophrenic, music-wise,” their bassist Scotty Ledgerwood says. “We used to joke that we were the only people who liked Black Flag and Black Sabbath, and we borrowed from them all. It was like: ‘We don’t like arena rock, and punk rock is too limited.’”

The story of Tina Bell and Bam Bam goes way beyond that ‘queen of grunge’ label. It’s about the diverse, tearaway roots of rock’s last truly game-changing scene. It’s about a young, bi-polar couple in early-80s Seattle, who started a band against pernicious odds. It’s about the pervasive roots of racial prejudice that have been so easily, consistently denied. Through a contemporary lens it seems absurd that Bell – a sharp, mesmerising but extremely warm presence, as remembered by those who knew her – stayed off the radar for so long.

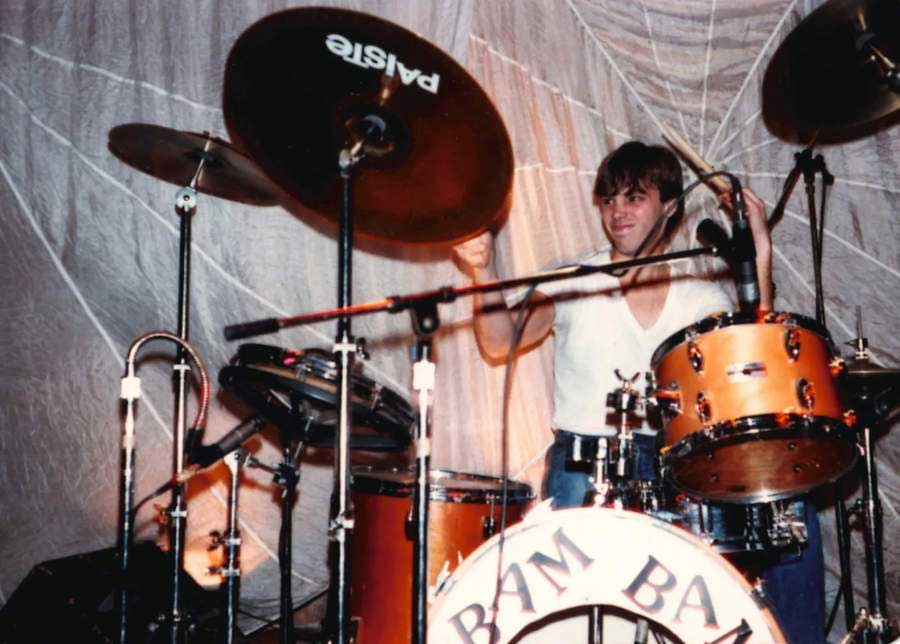

“Tina was one of those charismatic, gorgeous frontwomen,” Matt Cameron, Bam Bam’s original drummer (now in Pearl Jam), told the KEXP podcast. “She just had it.”

“It was this regal aura,” says Ledgerwood. “It was sort of a presence of grandeur, but it didn’t have the arrogance. When we met, she didn’t ask me a single thing about music, it was about family. She mostly asked about my wife and my boy.”

Scotty Ledgerwood lives in Ephrata, a semi-arid territory on the edge of the desert, about 175 miles from Seattle. Behind his house is a worn, scrubby road that seems to stretch into oblivion. When the wind blows, sand blasts. It suits Ledgerwood and his wife of over 40 years, Sandy ‘Scandals’.

“It’s bush and ’yotes and snakes,” he says with a chuckle, a little spaced out after a round of chemotherapy but in good spirits. “I had a four-foot bull [snake] on the porch a week ago, but they’re cool cos they keep the rodents out. We don’t have a rat problem here like we did in Seattle with the bullsnakes.”

Much of Bam Bam’s resurgence is down to Ledgerwood. Chatty and good-naturedly weird, he’s remained the band’s principal archivist and torch carrier, sharing photos, stories and updates – alongside animated videos via his eccentrically named company Buttocks Productions. He is still close with TJ and his family.

The story of Bam Bam officially began in 1983 when Ledgerwood, then an unemployed newlywed, answered Tommy Martin’s ad for a bassist in local free music paper The Rocket. Bus driver Martin and CheckMart worker Bell had fallen in love at Seattle’s Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, where Bell gave a performance of Eartha Kitt’s C’est Si Bon. Martin, partially raised in the Lyon area, was hired as her French tutor. By the time they met Ledgerwood, the couple were married with a young son.

Quickly, Martin, Bell and Ledgerwood formed a tight unit. Young, ambitious parents (all in their early twenties), their days were filled with songwriting, in between running after their offspring. Sometimes the three of them lay on the floor, their heads together, like children gazing up at clouds.

“The first six months of Bam Bam was my concept of what a band was my whole life,” Ledgerwood enthuses. “Kids getting together, almost instant pals. When I first met Bell, it was like that intimidation factor, and then, in a day, it was like we were best friends. And literally all day, four, five hours a day, five, six days a week, all we did was write. We didn’t have a social life, we didn’t go out, we didn’t do shit. All we did was write, write, write.”

“A lot of the Seattle scene at the time, this blue-collar town, the youth created their own scene because there was nothing else going on,” TJ adds. “A lot of them didn’t even know how to play their instruments, but they liked to make noise. Bam Bam was just very into music. My dad rehearsed all the time, they took their songwriting very seriously and they fancied themselves as proper musicians. And they were."

But they needed a drummer. Enter Matt Cameron, a teenager from San Diego, who answered their ad in The Rocket. Bam Bam became his first ‘proper band’ out of high school.

“When I took my drums over there and I set up and I met Tommy and Tina and Scott, Tommy and Tina had this beautiful, happy family,” Cameron told KEXP.

At the time, Seattle wasn’t on the rock map in the way it is today. Somewhat out of the way and not blessed with good weather, it was a territory ripe for a curious, open-minded assortment of acts in the early 80s.

“Seattle in the eighties was really in a flux,” Ledgerwood says, agreeing. “It was a very wiggly period. We had goths, we had punks, we had rockabillies, we had metal kids, and there was a strange melting of borders and barriers.”

Diving into this odd, free-spirited but unpretentious music scene, Bam Bam began to play local joints like The Metropolis, Gorilla Gardens, The Central and others that mostly no longer exist. For about a year there was also Behind The Grey Door, a subterranean club in the depths of an old warehouse. Misfits of all ages gravitated there; local punk band Cannibal squatted under the stairs.

“You’d have to come down these stinking, old…” Ledgerwood says, laughing at the memory. “Oh, man, ducking under pipes and shit, and all of a sudden a door opened up and you’d be on a big wooden dance floor. The first time I went there, guys were on a motorcycle in the middle of the dance floor, spinning round and round and round, and a skateboard ramp on the side, kids out doing their drinking or whatever. And all of a sudden a little trapdoor popped open and a huge cloud of marijuana smoke came out and a couple of guys were coming out, and I thought: ‘I like this place.’”

Bam Bam played there a number of times, delighting mixed audiences with their woozy, metal-edged fusion of punk, rock and soul. In many ways it was typical of this quietly fertile time for music in Seattle – far removed from the deeprooted, fashionable scenes elsewhere in the States. Ledgerwood recalls a young Duff McKagan playing at Behind The Grey Door in various lineups, allegedly including a short stint in Bam Bam. When he left town to audition for Guns N’ Roses, Ledgerwood adds, his leaving party was at the Bam Bam house.

Other stars-to-be entered the Bam Bam orbit too. The Melvins opened for them. Briefly, Kurt Cobain was their roadie. Shards of magic, in a haze of weed smoke, innovation and chaos that would ultimately see the likes of Nirvana, Alice In Chains, Soundgarden, Green River and Pearl Jam rise above their ‘proto-grunge’ predecessors.

“I played in tons of bands,” said Cameron, who was replaced by Tom Hendrickson. “But then when I would meet these people in Seattle that were just these kinda unicorn people, like Chris and Kurt, Tina, [Mark] Lanegan, Layne Staley. Just all these incredible singers. I think Tina is part of that generation that I came up with that had some of the best rock lead singers… I’m gonna say ever!”

Often, the lines between ‘forgotten cult band’ and ‘superstardom’ are extremely thin. There’s a sense of what might have been, had attitudes and timing been different.

In 1984 Bam Bam cut their debut EP at Reciprocal Recording, working with producers/engineers Chris Hanzsek and Jack Endino. This was before Nirvana and Endino were in the same studio in 1988 to record Bleach; before numerous others followed in their footsteps (Soundgarden, Screaming Trees, Mudhoney, Green River, Mark Lanegan…); before the Sub Pop label had turned Seattle into a world-famous indie hotbed.

At the same time, rock’n’roll was still an overwhelmingly white, male world. Women, and especially women of colour, were repeatedly sidelined. It’s an uncomfortable truth to acknowledge.

“Especially in the context of grunge, there were tons of women at the centre of that movement that are not celebrated today,” TJ Martin says, exasperated. “No one knows who the fuck Susan Silver is. Mia Zapata. Women who were behind the scenes. Megan Jasper at Sub Pop. There’s a ton. This idea that ‘we don’t see colour, we don’t see gender’ is just bullshit.”

If the aforementioned women were pushed under the rug, then Tina Bell was effectively erased. People expected Black women to be soul singers and hip-hop artists, not rock musicians. Doors remained closed, consigning Bam Bam to a small footnote that, overtime, grew easy to ignore. In 2011, noted grunge retrospective Everybody Loves Our Town referred to Bam Bam as a three-piece, not mentioning Bell at all.

Local musician Om Johari remembers seeing Bam Bam live as a teenager. For the young, aspiring Black punk rocker, the sight of Bell at the front was a turning point. “It definitely meant empowerment,” she told the Chicago Reader. “It also gave me a feeling of older-sister solidarity… We were persons who, because of our being, quote-unquote, ‘different’, had to accept that we were going to have to take considerable flak coming in and out of both communities.

"So you’re too weird to be Black, but you’re too Black to be weird in the white community. She represented somebody who was quintessentially punk, because she was definitely one of a kind.”

For someone as serious and open-minded about music as Bell, it was frustrating to have her skin colour and gender pose such obstacles. As Ledgerwood suggests, this frustration ate away at her throughout her life. “Years later we spoke of it,” he recalls, “and she wasn’t upset like, ‘Poor, pitiful me.’ She wasn’t seeking pity. She wanted a pragmatic understanding as to why people were so obsessed with colour.”

By and large, though, the audiences adored her. Ledgerwood still receives their letters. And as TJ tells us, there’s been a wave of appreciation from people who simply didn’t know that Bam Bam ever existed. Black, female rock and punk fans who didn’t realise they had a role model.

“That’s the thing that I’ve probably appreciated the most,” he says. “Meeting women of colour who have said: ‘I’ve always felt like I was a total weirdo and an outcast. If I would have only known someone like your mom existed, that would have brought me so much solace and peace within myself.’”

But prejudice and bad timing weren’t Bam Bam’s only obstacles. A more hidden factor in their early implosion lies in Tina Bell and Tommy Martin: two complicated, compelling characters, consigned to rock’s margins. In Bell’s case, her childhood provides clues as to the warm, sweet but extremely tough person she became.

“I can tell CBS: ‘Oh, I’m so proud, this is crazy,’ but the real story is so much darker,” TJ says with a laugh. “Their relationship when they were in the band together was super-volatile. Probably not as gnarly as the quintessential Sid and Nancy, but it definitely shares DNA with the classic sex, cheating on each other, drugs, power dynamics in the band…”

Tina Bell’s roots go back to Monroe, Louisiana. In the mid-1940s her mother’s family migrated north to find work, settling in Seattle’s Rainier Valley area. Born in 1957, Bell was the eldest daughter of 10 siblings – with three fathers between them. She learned to be indestructible early on, looking after her brothers and sisters when their parents weren’t around.

Musical at heart, the family made up songs as they did the dishes. Their mother played records by lounge singers, sparking Tina’s lifelong love of Frank Sinatra. They sang in the choir at Seattle’s Mount Zion Baptist Church (Bell herself wasn’t a religious person, which later created a rift between her and her mother).

“That’s where Bell got her chops,” Ledgerwood tells us. “Mount Zion is probably one of the most prestigious and beloved African American centres in Seattle; it’s a treasured site, it really is. White folks mourn Jesus, Black folks celebrate Him. I never felt such joy as when I was in there and they started singing.”

Her biological father, meanwhile, remained a mystery.

“What I’ve been told is that he was a race-car driver,” TJ says, “and he was mixed with Native-American, and that’s the extent of what I know bout him. My grandmother doesn’t disclose much about any of the other men in her life outside of Pa, who’s the one who basically raised the family.”

In high school, Bell was a cheerleader. From there she majored in drama at Washington State University. She stayed for a year, and wound up back in Seattle for a joint production between her old church and a theatre troupe linked to the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute.

It was Tommy Martin who turned her on to rock’n’roll. Through him she fell in love with Jim Morrison, adding him to her existing heroes like Nina Simone and Sinatra. They had TJ in 1979 and began to fill the house with lounge music, The Doors, Peter Gabriel, X, The Pretenders, early Metallica… These worlds came together, blurring into Bam Bam.

“[In] those early days I think there was legitimately an energy and a focus and a desire to be a recognised band,” TJ reasons, “and everyone was excited about that.”

But a dark side was beginning to grow. Both diagnosed with bi-polar disorder, Tina and Tommy had a marriage of joyous highs and deep, even violent lows. There were shouting matches. Physical fights. Guitars thrown out of windows.

With bills to pay and a son to support, Tina made ends meet as a hairdresser and a stripper. In the latter half of the 80s they moved to Europe for two years, hoping to find success for Bam Bam where Seattle had ultimately failed. It was the beginning of the end for the band, and their marriage. By 1990 they’d returned to the US and broken up, leaving TJ with Tommy as his primary caregiver. In practice, he spent a lot of time on his relatives’ sofas.

Today an articulate, good-looking 42-year-old, speaking from Los Angeles – fresh from the success of his Tina Turner documentary Tina – TJ Martin betrays little of the dysfunctionality he grew up with.

“People always ask me how I turned out so normal,” he says, laughing, “and I think later in life I got really angry, in my twenties.”

By that point, his father Tommy was taking cocaine and heroin. He admitted himself to a psychiatric hospital and began waves of self-medication. Through it all, he and Tina retained a difficult, strained kind of relationship.

“I think they loved each other a lot,” TJ says. “I don’t know if ‘friends’ is the right word, but there was such a deep history there that, later in life, I think my dad still admired and loved my mom and my mom tolerated my dad [laughs].”

As TJ suggests, their closeness took them to an unhealthy place. Most of grunge’s mainstays moved between groups before finding their ideal matches (Matt Cameron, for one, moved from Bam Bam to Skin Yard, to Soundgarden and, lastly, Pearl Jam). For Bell, Bam Bam was her rock and, arguably, a cage of sorts.

“It was the only band she was ever in,” TJ says, “so she could never escape her deep-rooted emotional and historical connection to my dad and the band itself. And every time my dad tried to start something new, his point of comparison for vocalists was my mom, always. There was so much love and so much friction.”

After Bam Bam folded, Tommy Martin remained in the Seattle scene for a while, trying to get new projects off the ground. TJ believes he had a mental breakdown, “coming to terms that his time was never gonna come”. Along period of depression followed, after which he returned to the scene as a sound man. Scotty Ledgerwood formed Called In Sic, which Martin joined in 2010.

As for Tina Bell, she withdrew from music – writing lyrics, studying astral charts and rarely leaving her house. Contact with her was sporadic. After TJ graduated high school she moved to St Paul, Minnesota for two years and volunteered at a church.

She eventually settled in the Las Vegas apartment where she lived out her final days. In 2006 TJ moved to LA and saw her more regularly. When he won his Oscar in 2012, for high-school football documentary Undefeated, she was there to see it. Later that year, she died of liver cirrhosis, following a long struggle with alcoholism and depression. She was 55.

“Everybody remembers her as someone who would flash you a big smile,” TJ tells us, “give you a big hug and genuinely want the best for you, and kind of hide her own demons. She always tried to show her best self when I was around and protect me from whatever kind of stuff she was battling inside. So an amazingly loving and warm person, [but] totally absent parent. My dad, a very present parent but the opposite. He vents. He brings you into his whirlwind of chaos.”

Ledgerwood had got back in touch with both of them, helping rebuild some old bridges. Both insomniacs, he and Bell had long phone conversations that rolled into the small hours. They reflected on past trials, and made plans for a Bam Bam reunion. Her death hit him hard.

“I feel like I let her down,” he says, sadly. “I don’t know what the hell I could have done, more than I’d done already. I was ordering her groceries and shit to make sure she gets what she needs, something she’ll eat to get her off the hard liquor. I’d get her these little bottles of champagne instead, and she loved those; that was one of my few tricks that worked [laughs]. But I knew something was wrong because I hadn’t heard from her, and then Tommy called and that’s when I knew…”

Tommy Martin died in 2019 following a lengthy battle with pain control and self-medication. Doctors, believing he was an addict, had refused him painkillers. After his death it was discovered that, in desperation, he’d been drinking three bottles of hard liquor a day and buying meds on the black market, and fell victim to a bad batch.

Today, TJ’s memory of his parents is of their best days. The giddiness of their twenties, when anything seemed possible. The capacity of love, perhaps, to mask red flags.

“Even though they were a pain in the ass, the thing that comes to mind is how fucking cool they were,” he says with a laugh. “Obviously there’s a rush of things that come to mind, but the image I have is [of] them in their youth and what their dreams were. So there’s a tinge of sadness, because I don’t know if they were ever fully fulfilled.”

Even with Bam Bam’s resurgence, it would be foolish to suggest that the balance of rock history has been redressed – that unsavoury biases, subconscious and otherwise, are now a thing of the past. Just as the likes of Poly Styrene, Neneh Cherry and Pauline Black still aren’t spoken of in the same breath as their male counterparts, the same is true of Tina Bell.

And yet her impact is resonating. Last year Om Johari, who became the singer with Bad Brains tribute band Re-Ignition (she has also fronted AC/DC homagers Helles Belles), led a tribute concert that included appearances from Seattle artists Ayron Jones, Eva Walker, Shaina Shepherd, Matt Cameron and many more.

Not long after, American station CBS aired a short documentary about Bam Bam. In spring this year their 1984 EP

\was released. Ideas for a film, and further live projects – featuring women of colour from outside Seattle – have been hinted at, while a physical reissue of Free Fall From Space (remastered by Jack Endino) is in the works.

“You’ve got these white, angst-filled guys, trying to find some kind of persona or aura to put forth, but Bell didn’t do that, because she already had that aura in her life,” Ledgerwood remembers today. “She suffered and found eloquent ways to share that suffering. She didn’t have to pretend; she was more pure rock’n’roll than any guy on that whole scene.”

The face of rock’n’roll won’t transform overnight. As with so many other cultural and social fields, the shift to a more diverse landscape involves rewriting decades of very white, very male dominance. A story like this one is another step towards achieving this. Another pebble thrown, with ripples spreading from it.

And perhaps this is Tina Bell and Bam Bam’s real legacy, more so than the music they created: laying a path for a new kind of rock age, colouring outside the lines of what people think rock stars ‘should’ look like.

“It’s stupid to think that this is an anomaly,” TJ says, affirmatively. “If you find yourself wanting to be a vocalist for a punk band but you’re a Black woman, you can fucking be a vocalist for a punk band.”

Bam Bam's Villains (Also Wear White) EP is available from Bandcamp.