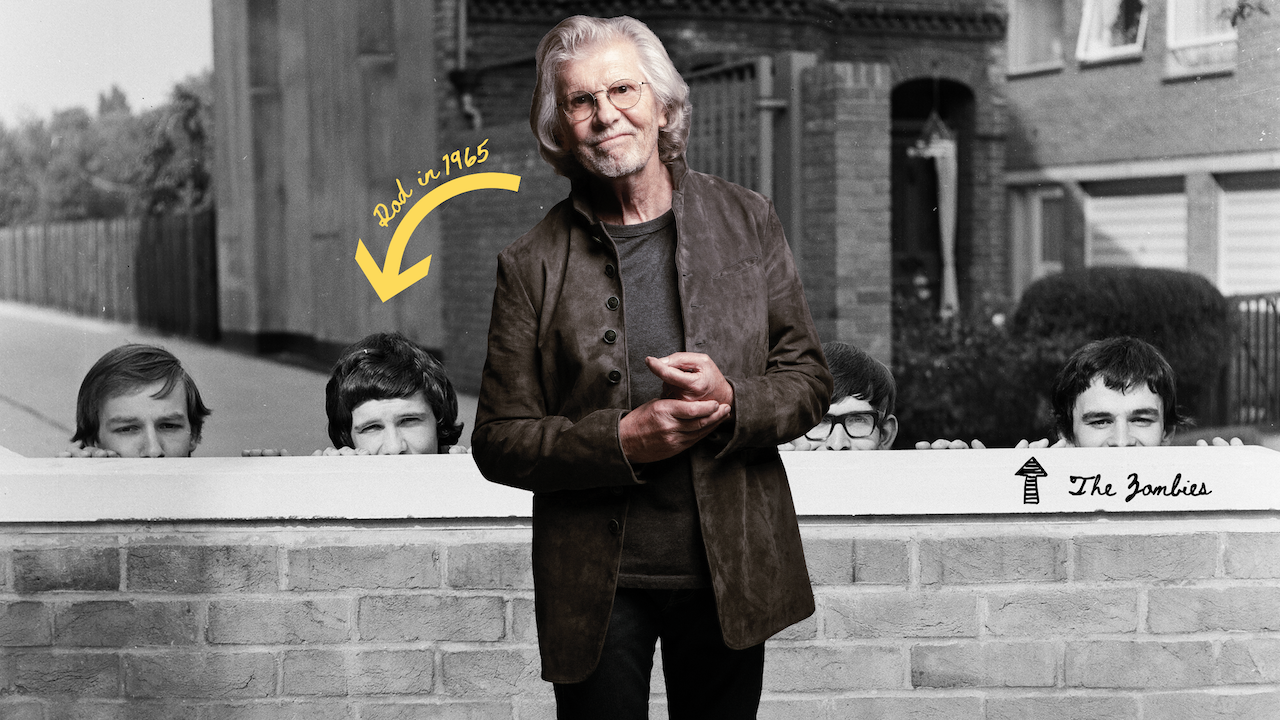

Rod Argent is a pretty satisfied man these days. The Zombies, the band he co-founded as a teenager in 1961, have recently returned from a sell-out tour of the UK, promoting their best album for decades. Different Game finds The Zombies doing what they’ve always done best: deftly orchestrated pop songs with exquisite harmonies, great melodies and heaps of musical invention.

Almost exclusively written by Argent, and voiced by Colin Blunstone (the other mainstay of the original lineup), it’s better than anyone has any right to expect from a band whose core duo are now deep into their 70s.

It’s hardly been straightforward getting here though. Having started out by gigging locally around St Albans in south-east England, The Zombies won a competition to find the “top beat group in the country” in May 1964, after which they were ushered into the studio by Decca. Written by Argent, debut single She’s Not There was an instant classic, hitting big both at home and in the US.

It also established the band’s sound, largely based around Argent’s dextrous keyboard-playing, informed by rock’n’roll, jazz and classical music. George Harrison gave it the thumbs up on BBC TV show Juke Box Jury, which delighted Argent no end. “He said, ‘Oh, well done Zombies. And if that’s actually their real piano player then he’s really good,’” Argent recalls. “I can feel my excitement even now. It was like having word from Mount Olympus.”

But a mixture of bad luck and mismanagement meant that The Zombies could never quite build momentum, despite the Billboard success of another Argent hit, Tell Her No. By the time they recorded their psych-pop masterpiece – 1968’s Odessey And Oracle – the band had more or less decided to split. They landed a posthumous North American hit with Argent’s majestic Time Of The Season, though its creator had already moved on. “We’ve never been musicians that would want to capitalise on things, we always wanted to look forward,” he explains. “When I first formed Argent I just wanted to explore a few boundaries and see where it took me.”

Argent were an altogether heavier, more prog-centric outfit, with the keyboardist sharing lead vocal duties with guitarist Russ Ballard. They enjoyed a decent run through the early 70s, scoring a signature hit with Hold Your Head Up, before calling time after 1975’s Counterpoints.

Rod spent much of the following decades switching between solo artist, producer or hired help, collaborating with such diverse names as The Who, Barbara Thompson, Nanci Griffith and Andrew Lloyd Webber. He finally reunited with Blunstone at the turn of the millennium. The pair tentatively cut an album under their own names (2001’s Out Of The Shadows) prior to reviving The Zombies in earnest three years later for As Far As I Can See…

The group have since become the primary focus of Argent’s creative life, releasing three more albums and spending much of the time on the road. “You’ve only got one life and when you get to the end of it, you’ve got to look back and say, ‘Well, I gave it my best shot. And I did things for the right reasons,’” he maintains. “Because when you start out playing, you do it through a huge feeling of excitement. And it’s still such a joy, playing with this band.”

Was it always going to be a musician’s life for you?

Yeah, I desperately wanted to be in music. When The Zombies started out, we were all at the stage where we were leaving school or, in [bassist and co-writer] Chris White’s case, leaving art college. That’s when we won the beat group competition and [Decca’s then head of A&R] Dick Rowe walked into our dressing room: “I’d like to give you a contract to make a session and a couple of singles with Decca.” We were over the moon. My headmaster had wanted me to apply to university, but I didn’t. I left it too late, deliberately. Everyone at that time thought being in a band was something which would only last for two or three years.

You were into Elvis Presley and rock’n’roll, but there’s always been a jazz component to your playing as well. You can really hear it, even in the very early Zombies songs…

We didn’t do it consciously. When I first heard Elvis, to my parents’ horror I didn’t want to hear anything else but the rawest rock’n’roll I could lay my hands on. And that led me to hear, by proxy, all the Black music that inspired it. It was just a wonderful time for music. When I was about 14 or 15, Miles Davis’ Milestones [1958] was the first record that I bought. I can still sing you the solos on that. A wonderful band with John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley. But it didn’t stop me loving Elvis and rock’n’roll as well. And I still love the classical music I was hearing, too, so it was all in there.

When we made She’s Not There I thought, “Okay, we’re being The Beatles in a funny sort of way.” I didn’t think of any other influences being there. But when I first met Pat Metheny, in America, he said: “Rod Argent, you wrote She’s Not There. That song made me feel I had a way ahead in this sort of jazz fusion that I wanted to do. All that modal stuff!” I wasn’t even conscious of that at the time, but now I know it came from just loving Milestones so much. So it did find its way through. Later on, Roger McGuinn from The Byrds said that Eight Miles High would never have been written without hearing The Zombies record and the improvisation on it.

After you’d written She’s Not There, did you realise you’d done something exceptional?

I’d only written one song before She’s Not There. I thought, “Yeah, I can write something that’s as good as The Beatles.” We were all very excited. I expected it to be a big hit and it was. It sounds ridiculous. And then when other things didn’t happen like that, I thought, “Hang on a minute…” I had no idea of any of the pitfalls that can affect every stage of what you do.

What kind of pitfalls?

I came to the realisation that everything has to be working for something to really come together and happen. We had management and an agency in the early days that weren’t good and I think we suffered very much from that. Our rivals at that early time were people like The Who – who had fantastic management from people that knew exactly what they were about – and the Stones with Loog Oldham and, of course, The Beatles with Epstein. But we didn’t have any of that, so that was a real disadvantage.

Was that essentially why you broke up The Zombies after 1968’s Odessey And Oracle?

We felt frustrated, for many reasons. There were two writers in the band – myself and Chris White – and we were both fine, because we had honest publishers, which meant I had a terrific income right from the start. But the other guys in the band were only breaking even, which was crazy, considering all the touring we were doing. On top of that, we were really downhearted with how our recent singles had been produced. The songs weren’t turning out how we imagined them. So Chris and I thought that if the band will break up, we have to try and produce an album ourselves. To at least show our own ideas of how we imagined the songs.

We managed to record Odessey And Oracle at Abbey Road and had a real ball. I think the Mellotron I used was John Lennon’s. I’ve always assumed it was because The Beatles had just walked out, having finished Sgt. Pepper. With the Mellotron I thought, “We can’t afford an orchestra, so we can use this for all these tone colours. It’s wonderful.”

What happened?

At the end of the sessions we thought we’d made something that was really good. But nothing was happening for us in the UK, so we thought we’d give it one last single. And if it wasn’t a hit, then we’d break up. So we put out Care Of Cell 44 and the only guy that played it was Kenny Everett. I remember Chris and I doing a show with him. He played the single then put on an album track too – I think it was A Rose For Emily. Cat Stevens, who was also on the show, came over afterwards and said, “Oh, man, I love that song. It’s beautiful.”

But no one else wanted to know, so we broke up. And then, of course, a year-and-a-half later, Time Of The Season went to No.1 in [American music industry trade magazine] Cashbox and No.3 in the Billboard charts. But I didn’t want to capitalise on that, because it didn’t feel like the right thing to do. I just thought,

“Okay, let’s move on to the next thing.” Chris White and I wanted to form a new band, Chris didn’t want to play anymore, but he wanted to be involved in the project and do some writing for it. And that’s how Argent started.

There’s a story about John Lennon offering to manage The Zombies if it meant keeping you together. Was that ever a thing?

Years ago, someone told Chris White that John Lennon had said, “I really wish I could produce The Zombies.” That’s the story I’ve heard. And that was a lovely thing to hear, because The Beatles were gods to us.

Was Argent a case of unleashing your inner rock beast?

I’d always loved the excitement in rock’n’roll, things with a real energy and drive. That’s why I loved the early Beatles records, because they had this soaring feeling. I actually think The Beatles were the first really progressive band, because they were always expanding what they were doing.

The first Argent album [1970’s Argent] is not that far away from what The Zombies were doing, but we started to expand the improvisation afterwards. And you write for the people around you. Bob Henrit, Russ Ballard and Jim [Rodford] all coloured what was possible and where we were going. We still loved melody and harmony, but if we discovered other things that felt exciting, we wanted to follow that as well.

You seemed to embrace more prog on the later Argent albums, didn’t you? From 1972’s All Together Now onwards…

Strangely enough, I only recently heard an EMI acetate of the very first thing that Argent ever worked up, from around 1970. It was a version of Aquarius, from Hair, but it’s unbelievably prog: 16-and-a-half minutes long.

Because obviously nothing’s written down with that, we just worked and worked at it. And we had it so that we knew it like the back of our hands. I didn’t even know a live recording of it existed. But someone brought it along to a Zombies gig and Jim Rodford’s phone number and name was on the acetate.

We’re currently in the process of trying to get it copied the best way possible. It’s extraordinary. That’s what we were doing back then, but that never made its way onto the first two Argent albums. I was really excited by some of the things I was hearing at that time.

I went to see Janis Joplin at the Royal Albert Hall [April 21, 1969] and Yes were the support band. I seem to remember they played Starship Trooper and Yours Is No Disgrace, which weren’t on record yet, and we were blown away. We thought they were absolutely fantastic. To me, Janis paled against what Yes were doing. I felt some pull within me that wanted to expand into those areas and see where it went – to use the keyboard and my own feelings of harmony that I’d heard in classical music and jazz. And for a couple of years I think we were all on that page.

So, what went wrong later on?

I think it got to a point where Russ wanted to go back to a more standard sort of song idea. It was never personal – I still love the guy – but musically there was a bit of tension within the band. And sometimes it didn’t feel like we were going in the same direction. So eventually it did apart. But when I hear the odd track from some of those prog albums – like Music From The Spheres from the Nexus album [1974], which I listened to about a week ago, for the first time in years – I think they sound fantastic.

Didn’t Rick Wakeman once say that the organ solo on Hold Your Head Up was the best thing he’d ever heard?

Yeah, I heard him say it! I think it was one Christmas two or three years ago, on Johnnie Walker’s radio show. The original Hold Your Head Up was six minutes long, but nobody would play it, except for Alan Freeman, who played it once a week on his show. Despite that, the single wouldn’t stop tickling just under the Top 50, so without asking us, the record company cut all my organ solo out of it and of course it became an immediate hit.

Anyway, Johnnie Walker played the long version and Rick Wakeman said something like, “In my opinion, that’s the greatest organ solo that there’s ever been on a record.” It absolutely made my Christmas.

What’s next for you?

We’re still trying to get the most out of this album at the moment. Getting played on radio is still difficult, but people who hear Different Game are giving it a terrific response. Management even told us that the average age of people that stream The Zombies is between 22 and 34. And I find that aspect of it beautiful, that we’re still able to relate to a young generation. That’s not something we ever expected to happen. It feels like a privilege to be at this stage in our careers and still be able to fulfil what we want to do. It’s just so exciting to play with this band. It’s very musical, but it really kicks arse.

How did you approach making Different Game?

I really wanted to go back to a very old-fashioned way of recording, in the sense of everybody being in the same room at the same time. The possibilities are endless with modern production, but there’s something about capturing a performance that goes slightly above what you would expect.

That’s what it was all about in the old days, because you had four tracks and had to play live together, so everybody responds minutely to how everybody else is playing. And it was great to get back to that. We were full of optimism and energy when it came to recording Different Game.

It felt really enlightening. I’ve been writing for Colin’s voice for so many years now, so I know it well. I know exactly where he likes to sing and how certain phrases will sound at a certain level. And I refuse to write anything that’s any lower than the originals, I won’t make any concessions to that at all. We do all the old stuff in the original keys and we do the new stuff in just as high keys too.

Why do you think that dynamic works so well between the two of you?

Colin still wants to do things for the same reason as I do: to make the best record he possibly can. We’ve made this last album and we’ve gone back to Odessey And Oracle in a strange sort of way, in the sense that we’ve completely produced it ourselves.

And Colin’s got the same feeling. In some ways, I think he sounds better now than he ever did. His voice has changed a little, as it will over the years, but I think it’s stronger than ever. Colin feels that he learned to sing by doing my songs, going right back to 1962. And I learned to write songs, in a way, by basically writing for Colin’s lead voice and what he could bring to everything. So that’s always been a really enjoyable dynamic. We’ve stayed friends over the years, even though we haven’t always seen a huge amount of each other, because we’ve been on different paths. But nevertheless, we’ve maintained that relationship.

What initially brought the two of you back together for 2001’s Out Of The Shadows?

I was living near Milton Keynes and had become very friendly with John Dankworth, who was developing his theatre there, The Stables. John believed in all music. So he’d have concert pianists, jazz groups and anything else that he thought was interesting. I saw a great concert there, where Keith Emerson played Tarkus on piano, with a big band. It was fantastic.

Anyway, John asked me to do a charity concert. I played a couple of classical pieces with a string quartet and I had a little jazz group, then I got the original Argent back together for about 10 minutes. Colin was in the audience and on the spur of the moment I asked, “Do you fancy getting up and doing She’s Not There with me?” We followed that up with Time Of The Season and it went down a complete storm.

A few weeks later he asked if I wanted to go out on the road with him, for just six gigs. I wasn’t sure I wanted to get back into all that again, because my memories of breaking up with Argent weren’t good. You’d travel in a huge lorry, with PA systems and all the old vintage instruments that would break down every day. And you’d have to have someone mend all the problems in the afternoon before you could actually go onto the stage. It seemed to get to the point where the actual playing was the last consideration. But in the end he persuaded me and I had an absolute ball. We gradually started doing a few more, and that’s now turned into 22-and-a-half years travelling around the world.

Different Game is out now via Cooking Vinyl. See the Zombies' official site for more information.