"The single Maggie May is a freak. A million-to-one chance. But the album has permanence and a lasting value. I still can’t see how the single is such a big hit cos it’s got no melody! Plenty of character and nice chords, yeah, but no melody.”

When Rod Stewart utters these words in October 1971 Maggie May, the hit he cannot understand and which a friend will tell him to leave off the album (“because it’s not commercial”) is stuck to the top spot on the British and US charts. Every Picture Tells A Story will match that feat at the same time – elevating Stewart from a respected journeyman into rock’s new superstar elite.

In a year dominated by George Harrison’s My Sweet Lord, John Lennon’s Imagine and Middle Of The Road’s bubblegum Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep, Rod Stewart becomes a household name.

With the Faces he notches up over 120 dates on the road in ’71, including four separate American tours. Two Faces albums are released – Long Player and A Nod Is As Good As A Wink… To A Blind Horse, spawning the boozy hit Stay With Me.

Suddenly Rod and the group are taken seriously – almost. Critics herald them as the new Rolling Stones – a funnier, more ramshackle model than the Glimmer Twins’ mob. Twanging the national nerve, by the end of ’71 Rod will be a millionaire, living in a 38-room mansion surrounded by 17 acres of Berkshire real estate with the Queen for a neighbour.

His fame and wealth will overshadow the Faces. The days when Ian McLagan recalled, “we were five blokes who shared the same haircut but only one hairdryer” won’t return. But the meteoric rise of Rod Stewart involves a great deal of luck.

Consider that when Archway Road-born Roderick David Stewart turned 26 in January ’71 he had very vague ideas about his future. “I’m looking for a song that’s probably been forgotten, that no one’s done for a time. Something that can fit my voice so I can sing it right, and something with a particularly strong melody.”

He felt confident about that soon to be famous throat. “It’s become more sandpapery, that’s an improvement in itself. I learned a lot from playing with Jeff Beck, which really helped a lot. I learned how to fit in with a guitar – how to be a lead vocalist. I think I phrase very well.”

Having produced half of old pal and mentor Long John Baldry’s It Ain’t Easy album (Elton John did second-side honours) Stewart used many of that album’s motley cast of characters for his own, Every Picture and the same Morgan Sound Studios in Willesden, complete with trusted engineer Mike Bobak.

Morgan was favoured because it boasted a mock pub, an establishment that saw major action when Rod’s merry men were around. Also part of the team was Rod’s Faces/Jeff Beck Group buddy Ron Wood. “I turned up promptly at each session with my guitars, a shoelace and a small wireless,” recalled reliable Ronald.

Despite a friendship that began in the Jeff Beck Group, they were chalk and cheese. Wood noted, “Rod’s the last person I thought I’d end up sharing a career with. We lead completely different lives,” while Rod commented, “I write lyrics best. Woody and I have got a really good combination, because he writes beautiful melodies, but can’t write words. I can’t write melodies at all, but I can words.”

Stewart was happy in charge. If the other Faces were irresponsible rogues Rod was a stickler for appearances, and keeping up to speed with the ledger. “I don’t get so much freedom with Rod as with the Faces,” Ron mused. “He’s made up his mind what he wants when we get into the studio. He moulds the musicians.”

Ian McLagan contributed significantly to the Every Picture album. In his mind’s eye the Rod-the-Mod concept was over. “The Faces are a rock’n’roll band but Rod’s a bit of a folkie at heart.”

Rod saw it differently: “Me and Woody are from the so-called underground. The Faces are more pop.”

Maybe the truth lay elsewhere. Bob Dylan’s Band albums were an inspiration for Stewart’s solo discs. He liked Neil Young and claimed to have been enthused by Van Morrison’s 1968 album Astral Weeks. (‘Claimed’ because Rod’s actual Van knowledge was sketchy: “Van doesn’t write his own songs, so he can’t conquer them.”)

Rod was ruthless when wearing his producer’s hat. The Faces rhythm section, Ronnie Lane and Kenney Jones, would appear on one Every Picture cut only, a version of The Temptations’ (I Know) I’m Losing You. Later chosen as a single, it was released with no group credit – for contractual reasons. Rod liked the number because he thought David Ruffin was the best singer in the world. But the Faces weren’t interested in recording it, so he took it instead.

According to Jones, “Rod used the Faces as a springboard. He kept the commercial stuff for himself. Rod was no fool. The Temptations song was easy. I was watching Sink the Bismarck! one afternoon at home when I got the call. I didn’t even take my drums; I used his regular drummer Mickey Waller’s [not even Waller’s but half-Status Quo’s and half-Free’s]. I got home in time to see the Bismarck sink.”

Mickey Waller had played with Stewart and Wood in the Jeff Beck Group two years earlier and had since appeared on Rod’s debut solo album An Old Raincoat Won’t Ever You Let You Down – known as ‘Thin’ to the cognoscenti, and The Rod Stewart Album to the Americans. Prized for his ‘Waller Wallop’, his other affectionate nickname being ‘Wanker Waller’, little Mickey didn’t own his own drum kit. He hated cymbals but always hit the snare’s sweet spot. If he had to play a solo he’d demand more money.

Many of the other players emerged from the fringes of the British music scene. Raffish mustachio’d violinist Dick ‘Tricky’ Powell, a trained architect and jazzman, played gigs in a local Italian restaurant in Willesden Green for wine and pasta payment. Scouser Sam Mitchell was a Dobro/bottleneck player with a reputation for licks and liquor.

Baldry thought Sam the greatest exponent of the National steel stringed guitar. Rod liked him enormously, especially his sense of humour. Twenty-year-old Sam’s opening gambit was usually, “How’s your wife, and my kids?” When he left he’d say, “It was a business doing pleasure with you.”

Rod’s regular pianist Pete Sears is not alone in recollecting, “The Every Picture period was the funniest time I’ve ever had in music.” But Powell and Mitchell returned to the anonymity from which Stewart found them and would later die of alcohol-related deaths.

Another Every Picture victim was Stewart’s co-writer on Maggie May, painfully shy classical guitarist Martin Quittenton. Waller introduced Rod to Quittenton when the latter was playing with Steamhammer at the 100 Club on Oxford Street, London.

Stewart befriended the jumpy guitarist, offering him a room in his Highgate home – later rented out to Baldry. “Rod found me and gave me work,” Quittenton remembered. “He was very kind. Rod and his girlfriend Sarah were hospitable. A lovely couple.”

The in-demand Sears flew in from San Francisco. Sears knew of Quittenton’s prowess, and had also played with Mickey ‘Finn’ Waller in Sam Gopal’s Dream, on London’s psychedelic rock circuit, and in ex-Blue Cheer man Leigh Stephens’s West Coast group Silver Metre.

As sessions took shape in January, Stewart had gathered an extraordinary line-up of mods, musos, hippies and be-bop beatniks. More oddballs were to arrive. His team falling into place, Stewart was stalling as he considered his follow up to Gasoline Alley. More drinker than druggy, he rubbished the idea that his last album had been made with psychedelic stimulation (“Funny, I made the album on a bottle of brandy a day”).

He had no grandiose ideas when it came to writing: “I pretend to be a songwriter. I try really hard, but it takes me three weeks to write one song. If I’m pressurised I can write lots of songs. I gotta do it, so I do.”

He needed to. Stewart had a five-album deal with Mercury-Phillips, brokered by A&R man and nominal producer Lou Reizner, as well as his Faces contract with Warner’s. He was adamant that the two should be distinct.

I made the album on a bottle of brandy a day

Rod Stewart

“I won’t use the Faces at all on my next record,” he said. “I might use Ronnie Wood a bit but we really must separate the two issues. Put the band over there, and my albums over here, and keep the music as far away from each other as you can. We can make nice heavy albums with the band – and I can do a bit of smooth stuff on the quiet.”

His yardstick was “make a solo album of really slow things, like a nice midnight-type album. There’s a wealth of musicians in England. I want to make a whole album like Bob Dylan’s Only A Hobo [a song he had recorded for his previous LP]. If I can sell an album like that I’d be more pleased than with Gasoline Alley.”

True to his word the very first track on the Every Picture sessions was yet another arcane Dylan song, recorded at Morgan during a break from the Baldry project. Tomorrow Is A Long Time was, as McLagan had noted, a folky choice with Quittenton on acoustic guitar, Powell’s old time fiddle and Ronnie Wood playing his new fixation, the steel guitar.

Stewart liked the results but had little idea where to go next. The working title for his imminent third album was – bizarrely – Amazing Grace, which would appear as a song, though not with the Scottish bagpipe arrangement he envisaged.

A raw version of this most traditional of ditties (folk singer Judy Collins’ interpretation was charting at the time) was knocked out with Sam Mitchell after Baldry’s album ended on a three-day furlough that necessitated the cancellation of the Faces’ first three gigs for 1971.

Back at work Stewart embraced a Ted Anderson song, Seems Like A Long Time, with Baldry and Madeline Bell from Blue Mink adding “vocal abrasives”. Rod had heard the song on Brewer & Shipley’s Tarkio LP. So easy on the ear it was practically MOR, this was standard hippy songwriter fare.

Taken in isolation, these three opening tracks were hardly earth shattering. By February, Stewart was struggling for direction. His deadline set for late May, he looked over his shoulder at whippersnappers like Free. “They’re knocking me out. What a tight band!”

His possible repertoire for the projected album was haywire. He seriously considered tackling I’d Rather Go Blind, a hit for Chicken Shack in 1969. He toyed with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ Out Of Time, surely the solo property of Chris Farlowe. He was even planning on covering Pete Townshend’s The Seeker, a hit for The Who in recent memory.

Sessions shelved, Rod embarked on the Faces’ third US tour that spring. There was now a buzz around the group. They climaxed at New York’s Capitol Theatre in Port Chester (billed as Rod Stewart and The Small Faces) with a decadent end of tour party on April 4, at which pharmaceutical cocaine was consumed for the first time, according to Wood.

The provider was a notorious concentration camp survivor Freddie Sessler, later to be Wood (and Keith Richards’) partner in crime. Sessler, who was independently wealthy, came armed with limos full of New York’s most ferocious groupies. He also had pockets stuffed with vials of pure Merck – 98 per cent proof medicinal cocaine. Rod was soon expressing concern for Woody’s welfare.

Yet while other chaps snorted, smoked and guzzled across America, screwing anything that moved and destroying anything else that wasn’t nailed to the floor, Stewart – though no angel – resisted the excesses. He didn’t smoke, and only ate the occasional lump of hash for a dare, making the others laugh to hear his stoned nonsense.

A la Jeff Beck days, Ron and Rod were still sharing a room. They pretended to be gynaecologists, dressing in white coats with stethoscopes and inviting groupies to be examined in their ‘clinic’, decorated with underwear the road crew rescued on stage.

If consultancy got boring, a favoured pastime was demolishing the room and sending the contents to the lobby by lift. Or drawing cocks on Holiday Inn paintings. Debagging their manager, a fragrant Irishman from the Curragh called Billy Gaff, then pushing him into the corridor alongside girls queuing outside their waiting room, was another regular jape. It was Gaff’s job to placate the management at sundry Howard Johnsons and Holiday Inns. And then dock the band’s wages.

Luckily Rod also brought along a notebook. In America he scribbled down a couple of songs. Every Picture Tells A Story was a more or less accurate account of his teenage years as a beatnik travelling round Mediterranean Europe in the early 1960s, getting moved on by cops (“French police wouldn’t give me no peace. They claimed I was a nasty person”), neglecting his personal hygiene “My body stunk but I kept my funk”) and eventually being deported, thanks to the British Embassy agreeing to front his BOAC fare.

The other song, named Maggie May after a notorious Liverpool docks prostitute, found Rod recalling “my first shag” at the Beaulieu Jazz Festival in 1961. “It was in a tent,” he mused. “I was 16 and it lasted precisely 28 seconds. She was older and bigger than me. I don’t think her name was Margaret.” Intriguing documentary footage exists of Stewart outside a Beaulieu newsagent. He’s wearing an army jacket festooned with Ban The Bomb badges and a broad smile.

The Faces returned to play at the Orchid Ballroom in Purley – not much Merck in Purley – then Stewart was back in Morgan with Waller, Wood, Sears and bass player Andy Pyle, who’d shared the Faces recent road trip as a member of Savoy Brown. Ostensibly the headliners, Savoy Brown were blown off stage so many times the Faces usurped them.

Pyle remembers: “The song Every Picture was recorded immediately after that eventful tour. The atmosphere in the studio was the same good-natured party vibe. It was over in two hours with no rehearsal and no repairs.” Maintaining this buoyancy, Stewart chucked Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup’s rock’n’roll standard That’s All Right into the Morgan pot.

Pete Sears: “As usual we went over the basics at Rod’s house and tried to make it our own. We knocked off something raw and spontaneous… Sophisticated in a subtle way. That summed up the album. Rod and his cast fused folk, blues rock and soul, even Martin’s classical leanings, into one fresh sound.”

Sears describes Rod’s approach as “the antithesis of sterile production line. The method was go over to Rod’s place in the afternoon where he sang at his grand piano. We whipped up a quick arrangement, went back to Morgan, hit the downstairs pub, made the recording, went back to the pub. It was his idea for me to come in half-way though on the song Every Picture Tells A Story, to add impact.”

It was also Stewart who coached Wood into arriving at the line “I was accused…” building his guitar solo to a place that made Jagger and Richards sit up when they heard it. Wood, who was listening to a lot of Duane Allman, and the Flying Burrito Brothers’ pedal steel player ‘Sneaky’ Pete Kleinow, came of age here, dubbing 12-string to electric and then adding slide guitar.

Wood’s confident musicianship allowed Rod to blossom, a fact not unnoticed by Ian McLagan. “The sessions were a lovely piece of work. Rod was interesting as a solo artist. Away from the Faces he was very confident. There wasn’t much talk. Just play. He didn’t waste studio time because time was money. He was a good producer but he was lucky to have Mike Bobak as his engineer. Mike was a quiet chap. He needed to be, because we were all terribly noisy.”

Without Bobak’s input Every Picture was a nonstarter. Credited as engineer, his role was vital – not even Rod Stewart could sing, dance and operate a 16-track mixing desk at the same time. Bobak has vivid memories of life inside Studio One.

“Rod wasn’t in the studio when I was mixing. He was in the bar. Rod was the producer in that I didn’t tell the musicians what to do. He’d say if he didn’t like something, but I didn’t tell him if I didn’t like what he was playing. Despite our long relationship I was a hired hand. He was the artist and I wasn’t. I got no royalties. Rod worked everything out at home and put it together in Morgan. ‘This needs violin – where’s Powell? This wants Dobro. Where’s Mitchell?’

“It was fun and games for them but with serious work between 7pm and 10pm. Never later. They’d go to the bar, I’d knock off a mix cassette, give it to Rod, and he took it home for perusal. He had a routine. Two hours were allotted to each track. He didn’t want to spend a lot of money because studios were expensive. The musicians were collaborators. He conducted on the shop floor. He was quite old school in his attitude. He only played a bit of acoustic guitar on the album. He wasn’t very good. Bit of a strummer.”

It was in a tent. I was 16 and it lasted precisely 28 seconds. She was older and bigger than me

Rod Stewart

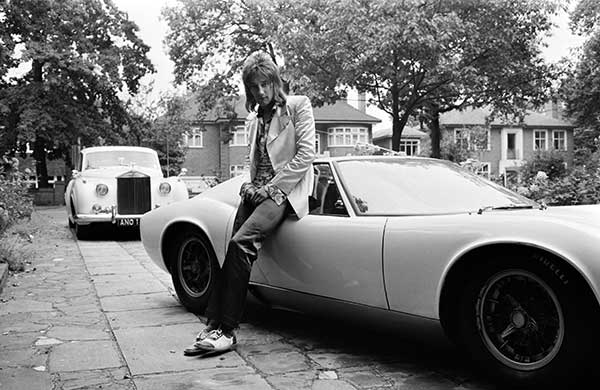

Bobak worked with Stewart throughout his Mercury career and started noticing a change. “He was alright during Every Picture. Then stardust bit him. He thought he was the bee’s knees. Always preening himself, fiddling with his hair, trousers. He loved his motors. Every night you’d hear his wheels screech off.”

Occasionally Rod lost his temper. “He was quite moody if things weren’t going well,” says Bobak. “I remember him shouting at me and the tape op Phil. I don’t know why. I wasn’t playing the songs. If he got tense he could be very rude.”

During an attempt at Maggie May, Ron Wood realised he’d played a blinding solo that the engineers hadn’t tracked. A furious Stewart threw a glass of wine over young Phil and stormed off to the bar, effing and blinding.

Stone The Crows vocalist Maggie Bell saw a sweeter side. Maggie was living with Alex Harvey’s brother Les in Highgate when she got Rod’s call. “I thought he was an absolute gentleman. Very professional. He arrived in his yellow Lamborghini. Smartly dressed, everything matching and expensive. He was wearing a pink jacket, pink satin trousers and a white silk scarf. What a dandy! I was in patched denims. In the car we talked about Scotland.

"I told Rod he reminded me of Denis Law. I was just down from Glasgow, so I was nervous. He gave me the lyrics for the song Every Picture Tells A Story. ‘See what you think.’ We did it in two takes. Years later people thought I was the Maggie in Maggie May,” Bell laughs. “Rod wasn’t my type.”

Bell was paid £30 for her work. Her arrival during the line ‘Shanghai Lil never used the pill/ She claimed that it just ain’t natural’ is among the album’s most priceless moments.

Stewart, who’d loved singing with Julie Driscoll in his mid-60s group The Steampacket, and with Toxteth lass Beryl Marsden in Shotgun Express (they included Mick Fleetwood and Peter Green), was ecstatic.

“It’s one of the two best songs I’ve ever written,” he gushed, perhaps forgetting that Wood actually wrote the music. His other favourite was Mandolin Wind, which Rod was solely responsible for composing. It needed pepping up. He’d demo’d it for the Faces but they didn’t rate the song.

Martin Quittenton recalls the original: “Rod played it to me on the acoustic guitar. I don’t know where the song came from. We never talked like that. We just did it.”

With Quittenton and Wood’s guitars underscoring Stewart’s plush ballad what the song lacked was… a mandolin! Enter Wallsend musician Raymond Jackson from Lindisfarne who, like both Bell girls, had played on the Baldry album three months earlier.

“I drove down from Newcastle to add a mandolin overdub. The song was very country-ish. I remember Rod and his girlfriend were watching me play through the glass. I finished and he seemed pleased. Then he said, ‘I’ve got this other song called Maggie May. I don’t know what to do with it. I might not even use it and it probably won’t even go on the album but I’ve got nothing to put on the end so can you put some mandolin down?

"I had two minutes to improvise around the chords, then I was playing, and they double tracked it until it was almost orchestral. Suddenly they liked the song! I’d got the impression it wasn’t going to be used at all. Now the people at the mixing desk were looking at each other in delight. They were applauding.

“That night Rod invited me home. I followed his white Rolls-Royce in my little Bedford HA van and ran out of petrol. I had to get Rod to pull over at Child’s Hill and wait for me, because he wasn’t holding back.”

Chez Stewart the young Jackson was treated to Sarah’s warmed-up shepherd’s pie and a few beers. “We watched football. Rod had one of the first portable Sony black-and-white video machines in his lounge. Then I drove home and kipped on a mate’s floor in Olympia.”

Jackson’s contribution to Maggie May became controversial later when he asked for more than the £15 he was paid as a session man.

“It was annoying that Rod left my name off the credits [‘The mandolin was played by the mandolin player in Lindisfarne. The name slips my mind’ according to the sleeve]. I asked him later: ‘Surely you could have got the information from the company?’ But he didn’t apologise. My mandolin made it whole, if you like, glued it all together. The song didn’t have a definitive chorus or middle eight. It was unusual.”

Some said a mess. And yet now it was good enough for a single’s B-side, at least. Rod still wouldn’t have put it on the album – except that Mercury told him ever so politely that the album was way too short by at least six minutes, and since half of it was other people’s material, could Mr. Stewart kindly get off his arse…

Maggie wasn’t all Rod’s work. He’d first attempted it with Ron Wood in an American hotel room in March, the guitarist vamping around the opening to Dylan’s It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue. Now Martin Quittenton shaped the chord sequence in Rod’s shag-piled lounge and composed the acoustic intro, christened ‘Henry’, on the Piccadilly Line Tube a few days later. A pretty little madrigal, ‘Henry’ was really conceived as a time-filler. It would appear on some versions of the single, but not all.

According to Quittenton, Rod finished the Maggie lyrics in a desperate hurry. “We didn’t think it was very good,” he recalled. “Never in anyone’s wildest dreams was it a pop standard.”

Evidently Stewart thought the song had something, since he asked Ian McLagan to overdub a Celeste part. “I did what he asked and it was rubbish. I’d also cocked up the piano intro to I’m Losing You, but it worked, so I cocked it up every time we did it live for good measure."

Rod was OK during Every Picture. Then stardust bit him. He thought he was the bee’s knees

Engineer Mike Bobak

One other song required a tinker – Rod’s version of Tim Hardin’s classic Reason To Believe. Rod rated the doomed genius Hardin highly and expressed a desire to produce him. Enter burly South Londoner Danny Thompson from folk group Pentangle, accompanied by his 19th-century double bass ‘Victoria’.

“I knew Rod from Marquee days when he used to see me with Alexis Korner and from meets on the road, when Pentangle and the Faces shared ahotel,” says Danny. “He wanted me to replace Ron Wood’s electric bass part with my acoustic. I doubt it took 20 minutes. After the playback, I’m off. Rod and his girlfriend, who was wearing thigh-length leather boots, saw me to the door and he held my bass while I got my car, an S1 Bentley.

"Rod’s jaw dropped. ‘I’ve always wanted one of those!’ He was an endearing bloke, a proper geezer. I did it because I thought Tim Hardin – who was huge on the folk circuit – would get a load of money. I didn’t even get paid. He still owes me 20 quid. He said, ‘I’ll make it up next time.’ But he never did.” Billy Gaff would soon manage Hardin who was in the grip of heroin addiction. He was a hopeless case, but thanks to Stewart most Hardin compilations are called Reason To Believe.

In early May, Bobak had the album ready to send to New York for mastering by Mercury’s production boss Len Dimond. The sleeve was given to American artist John Craig who came up with a 1920s Art Deco look.

“The front image with the ‘Classic Edition’ typography was borrowed from a piece of old RCA sheet music. The illustrations on the back were Edwardian postcards, nostalgic 1910 images that seemed to fit the songs – which I hadn’t heard!” says Craig today. “Rod had no input. I guess he liked it because I did his next album, Never A Dull Moment. If people like the cover it’s serendipity. In the age of the gatefold sleeve you could have a lot of fun.”

The cover photos and an inner poster were taken at a Faces gig in the Fillmore East on February 17. Craig hand-tinted Lisa Margolis’s photograph, accentuating Rod’s cockerel barnet (he was born in the year of the Rooster), painting his lips red and his microphone gold. The package, more lavish in America than Britain, was now ready. Anyone want to hear it then?

Expectations were moderate. There were no full-page adverts. The music press carried two teasers for the album: one featuring tongue-in cheek text from Rod himself: “Like all great art, great wine, great craft, and great sex, Rod Stewart’s third album took a long time in coming….”

Before packing his bags for the next American tour Rod sent old mate John Peel an advance tape of the album. Only a year earlier the agreeable DJ had been lending Stewart and David Bowie the odd half a ton: “They said it was for art labs but they spent it all on velvet trousers, and nights at the Speakeasy.”

Intrigued by what looked like a haphazard selection, Peel started playing Mandolin Wind on his show and announced: “D’you know, I think that may be the best thing young Rodders has ever done.”

The ball was rolling. The band left for America as local heroes but Rod returned to the UK a superstar. On July 9 Every Picture was released and the Faces blitzed the Philadelphia Spectrum. A local DJ, given a pressing of Reason To Believe/Maggie May, was inundated by requests for the B-side.

The tour took off. There were riots in Dayton, crowd invasions in Chicago and all-night parties everywhere else as the Faces – assisted by pharmaceutical cocaine that blew up into a cloud when it reacted with air – were blown across the USA.

Kenney Jones remembers: “Mayhem. There was lots of drinking and cocaine and girls in every corridor. I never took drugs because they messed up my timing, but I was surrounded by it all. Drinking was rife. Horrible stone bottles of some muck we called Stanley Mateus and plenty of brandy.”

After they’d played Long Beach California, Apple Records executive Jack Good threw a party at which Rod met his soon to be new girlfriend, 18-year-old Dee Harrington, an aspiring model and glamour girl. He came back to England with her as his first trophy blonde and they set up home in Rod’s mock-Tudor spread in Winchmore Hill. Sarah returned to her flat in Notting Hill Gate and never uttered a word about Rod again in public.

Reason To Believe was released in early August but was soon listed as a double-A side once Maggie May saturated the airwaves. By October the single was number one in America and Britain, and so was the album. First performed on Top Of The Pops on the 19th the single became a permanent fixture on the programme that autumn, featuring eight times; one that included Peel pretending to play Ray Jackson’s mandolin part.

“I remember Rod wore a crushed velvet purple suit, and he fell off the stage. We had to restart the whole show,” said Peel.

The Faces were triumphant when they kicked butts and footballs at the August Bank Holiday Weeley Festival on the 28th. Resplendent in a pink satin suit designed by Rod’s man Andreas (“he makes me look tarty”), his feet platform boot shod by Bowie’s cobbler, a bare-chested Stewart brought the Clacton crowd to its feet as he introduced Maggie May: “Here’s a song about a schoolboy what falls in love with a dirty old prostitute.”

By the time they encored with Every Picture Tells A Story, Essex blood was so inflamed that when T. Rex headlined they were roundly booed, while the onsite caterers staged a pitched battle with several chapters of the Hells Angels. The Faces were paid £4,000 and departed as heroes. Magic stuff.

Similar pandemonium followed on September 18 at the Oval Cricket Ground’s Goodbye Summer Show – A Concert In Aid of the Famine Relief for the People of Bangladesh, featuring The Who, Mott The Hoople, America and Lindisfarne. By now sessions for the Faces third album, A Nod Is As Good As A Wink… To A Blind Horse were underway and the crowd was treated to an early version of the band’s one and only US Top 40 hit, Rod and Ron’s Stay With Me. In Britain that reached number six. The ackers were rolling in.

Martin Quittenton was on an open-top 31 bus on Worthing sea front when he heard Maggie May for the first time outside of the studio. “I was on my way to work in a music shop and I heard it coming from a juke box in a pub that had its doors open. Someone told me it was number one. I flinched every time I heard it. I didn’t feel proud, I felt vaguely satisfied.”

Sadly, a few years later Quittenton fell foul of the music business and suffered a severe breakdown. By his own admission Martin could have cashed in with Rod. “He asked me to go to America, but I was well on the way to a breakdown and it was impossible for me to go,” he told Smiler magazine in 1992. He retired on modest royalties, sold his guitars and moved to Anglesey to open an animal sanctuary.

As the year ended Stewart was wealthy and famous. These were blissful times. “When Maggie May went to number one we all went out and got drunk. The whole Stewart clan. The drinking went on for a long time, and why not?” he asked. It was a proud day when he gave his parents – Scottish Bob and Cockney Elsie – his first Gold Record.

“That was more gratifying than any big cheque or new car. My whole family had stood by me. They never said, ‘Get yourself a day job.’”

But big cracks had appeared in the Faces happy-golucky façade. During their sixth US tour – November and December – with Maggie-mania sweeping the States – they were still billed as ‘Rod Stewart and…’ “That was really heartbreaking for me,” Rod reckoned. “The boys all went, ‘Fuck it, don’t worry’, but I could tell Ronnie Lane and Ian McLagan were hurt, because they’d got away from a somewhat egotistical singer in Steve Marriott and they didn’t want that again.”

That December Stewart was presented with five Gold Discs at the Amsterdam Hilton for sales in various countries. Despite the success of A Nod Is… the Faces won nothing. Ronnie Lane wasn’t surprised. “Rod’s records have been better than the band’s. He works in a weird way. He does an album in a week. He goes in and crash, bang, wallop it’s finished. Everyone just strolls in, doesn’t give a shit and it comes out great.”

By way of justification, Stewart let rip three years later: “The looseness that the Faces were known for just became too loose. It was such an unprofessional band. How many times can you get away with being an hour and a half late at a gig for $15,000? You can’t go on doing that, year in and year out.”

Looking back, it’s obvious that Every Picture Tells A Story was Rod’s defining moment. It is one of the greatest albums made in the early 70s. Even old mate David Bowie was impressed enough to copy Rod’s hair-do for his album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, where he also covered It Ain’t Easy, the Ron Davies song Rod suggested to Baldry.

Rolling Stone magazine voted Rod rock singer of the year in their end of 1971 poll. NME readers elected him ‘Best New Disc and TV Singer Of The Year.’ Melody Maker gave him their Pop Star of the Year gong. Yet Stewart never matched Every Picture again. His next recordings were fine, but they were inferior carbon copies.

In a reflective moment Stewart acknowledged, “Every Picture was a great album to make. I wasn’t living up to anything. No one told me to make a single; I just bunged Maggie May on because that was all I had left to give the company. After that? I just hoped for the best. I really miss that spontaneity.”

As for the woman who inspired Maggie May: “If she’s still alive she’s in her late 60s now,” recalled Rod in 2007. “Cor… what a dreadful thought.”

Thanks to Pete Sears, Mike Walton, Tim Ewbank & Nico Zentgraf. This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 164, published in November 2011

![Rod Stewart - Maggie May - TOTP -1971 [Remastered] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/W49ltVJ-Gnc/maxresdefault.jpg)