Even the biggest bands in the world have to start something – and for the Rolling Stones it was in the smoky blues clubs of London in the early 1960s. In 2007, Classic Rock rolled back the years to look at the birth of the legend – and the people who fell by the wayside

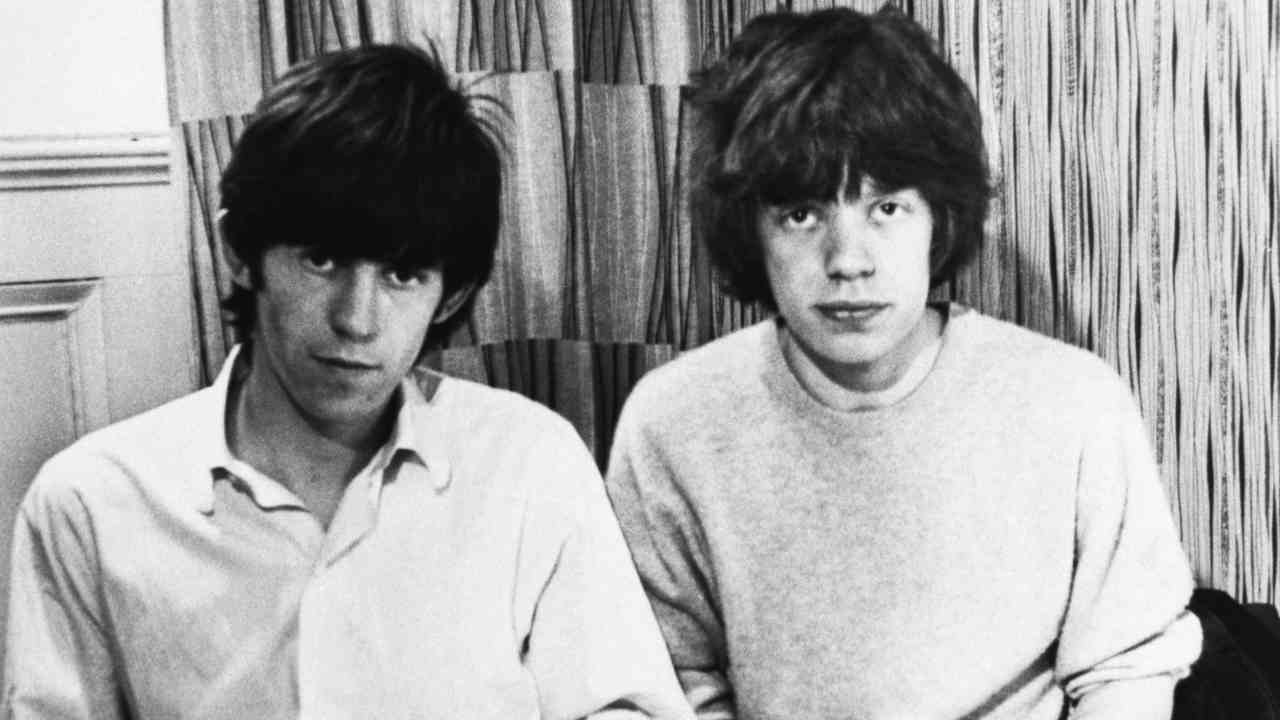

It was somewhere towards the end of 1961, sitting together in a railway carriage, that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards made a deal. It was unspoken but undeniable and almost spiritual. Richards later likened it to “Robert Johnson at the crossroads”. Jagger and Richards, complete opposites in every other way, had bonded at once and forever over music.

They weren’t exactly strangers on a train. Both were born in Livingstone Hospital in Dartford, Kent, in 1943: Jagger on July 26 and Richards on December 18. As children, they were neighbours and playmates, together attending Wentworth Junior County Primary School, with Mick in the year above. They remained friends until Jagger passed his 11-plus exam and moved up to grammar school. Richards entered the local tech a year later, and they lost touch. By now, their families had moved, the Jaggers to Wilmington and the Richards to another part of Dartford.

Through their teens, their interests diverged. Mick was confident, organised, keen on basketball, cricket and football, and bright at school, where he was a prefect. Keith was shy, sensitive, unconventional, alienated by sport and bored by his education.

Jagger won a scholarship to the London School of Economics in 1961. Richards, a bit of a scruff, had already been kicked out of tech after too many days bunking off to play snooker, and had enrolled at Sidcup Art School.

That’s where he was going when he bumped into Mick Jagger at Dartford station. And what he noticed – and coveted – was the bunch of American albums Jagger was carrying under his arm: blues by Muddy Waters, R&B by Chuck Berry. Keith couldn’t afford the price of these expensive imports, although he had a few singles. This was the music he loved; it was a cult interest in the UK.

He said to Mick: “I can play that shit. I didn’t know you were into that.”

Jagger responded: “I’ve even got a little band.”

Both had started playing guitar. They talked excitedly about the great American gods of blues and R&B, and by the time the train stopped at Sidcup, they had already forged one of the world’s greatest musical alliances, one that would survive huge differences and hostilities as together they fronted more than 40 years of The Rolling Stones.

But it wasn’t their band to begin with: it was Brian Jones’s. Brian was a blues fanatic. Born in the Park Nursing Home in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, on February 28, 1942, he was a natural musician who had easily mastered the piano, recorder, clarinet and washboard by the age of 15. He then progressed to playing sax and guitar with various local jazz outfits.

Jones was a clever but lazy and rebellious scholar at Cheltenham Grammar. He left with a raft of qualifications and no intention of using them. Determined to make music his life, he drifted in and out of various unskilled jobs and travelled to London for weekends. There, he became besotted by the sound of the blues, but his moment of epiphany happened closer to home – at Cheltenham Town Hall – when he first heard Alexis Korner play an electric blues set.

Bursting with excitement, he introduced himself to Korner, who gave Brian his address in London and became his mentor. Now Jones bought an electric guitar and practised feverishly, working for untold hours on his slide technique and soaking up records by Elmore James, Robert Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf.

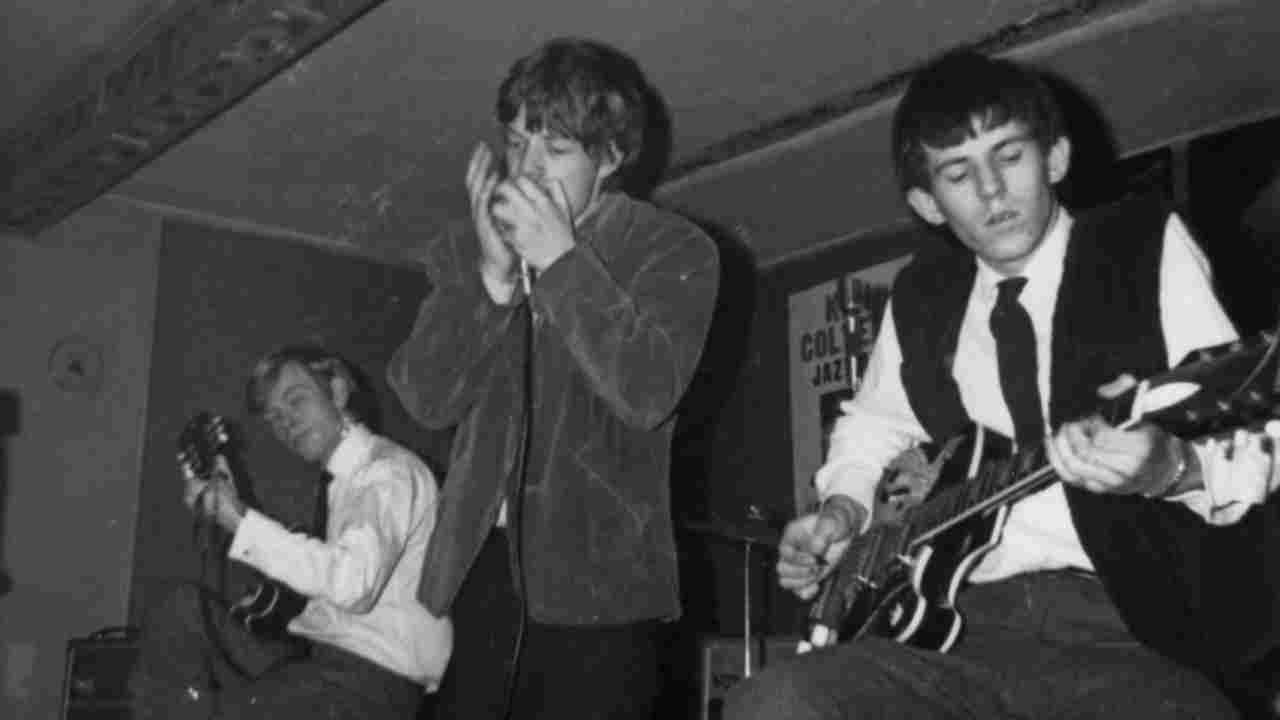

In March 1962, Alexis Korner opened a weekly R&B night at the Ealing Jazz Club in west London for his own band, Blues Incorporated. Brian Jones was among the sardines squashed into the room that first night. And when he returned the next week, he was invited onstage to play with Korner, whose line-up included harmonica legend Cyril Davies, saxophonist Dick Heckstall Smith – and drummer Charlie Watts.

On April 7, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were in the audience at Ealing to see Brian Jones once again sitting in with the band. Both were astonished by his performance of Elmore James’s Dust My Broom: it was the first time Keith had heard anyone playing electric slide guitar. Chatting later to Mick and Keith, Jones mentioned that he was putting a band together.

Jagger and Richards had already formed a group called Little Boy Blue And The Blue Boys, inspired by Jimmy Reed, Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. After their fateful meeting on the train, they’d started rehearsing upstairs at Jagger’s family home with a mutual friend, Dick Taylor. Taylor (who would come to prominence as lead guitarist with the Pretty Things) played drums. Jagger gave up the guitar to sing and play harmonica, leaving Keith to the fretboard. Other friends dropped in and out, and Dick Taylor eventually moved to bass.

Mick and Keith had each, separately, been in bands with Taylor. Jagger had met him at Dartford Grammar, and they’d formed an R&B group that rehearsed for two years but never played a gig. Jagger’s only public performance was at a church hall in 1960, singing a Buddy Holly song. Reportedly, it was completely dreadful.

Taylor next befriended Keith at the Sidcup Art School where they and another friend, Mike Ross, formed a country and western combo. They managed one gig. Richards and Ross missed the last train home and spent the night in a bus shelter.

Little Boy Blue And The Blue Boys never made it on to a stage at all, although they did make some recordings, which Jagger sent to Alexis Korner. As a result, he was invited to join Blues Incorporated in May, sharing vocals with guests including Long John Baldry and Paul Pond, later known as Paul Jones in Manfred Mann.

Brian Jones’s band, meanwhile, was coming together slowly. He recruited Ian “Stu” Stewart, a pianist from Cheam, Surrey, through an ad in Jazz News, and the pair began hiring rooms in pubs around the West End for rehearsals and auditions. They recruited a widely respected guitarist, Geoff Bradford, and singer/harmonica player Brian Knight.

Knight lasted only a few weeks before leaving to form his own band, Blues By Six. Bradford followed him into that group shortly afterwards.

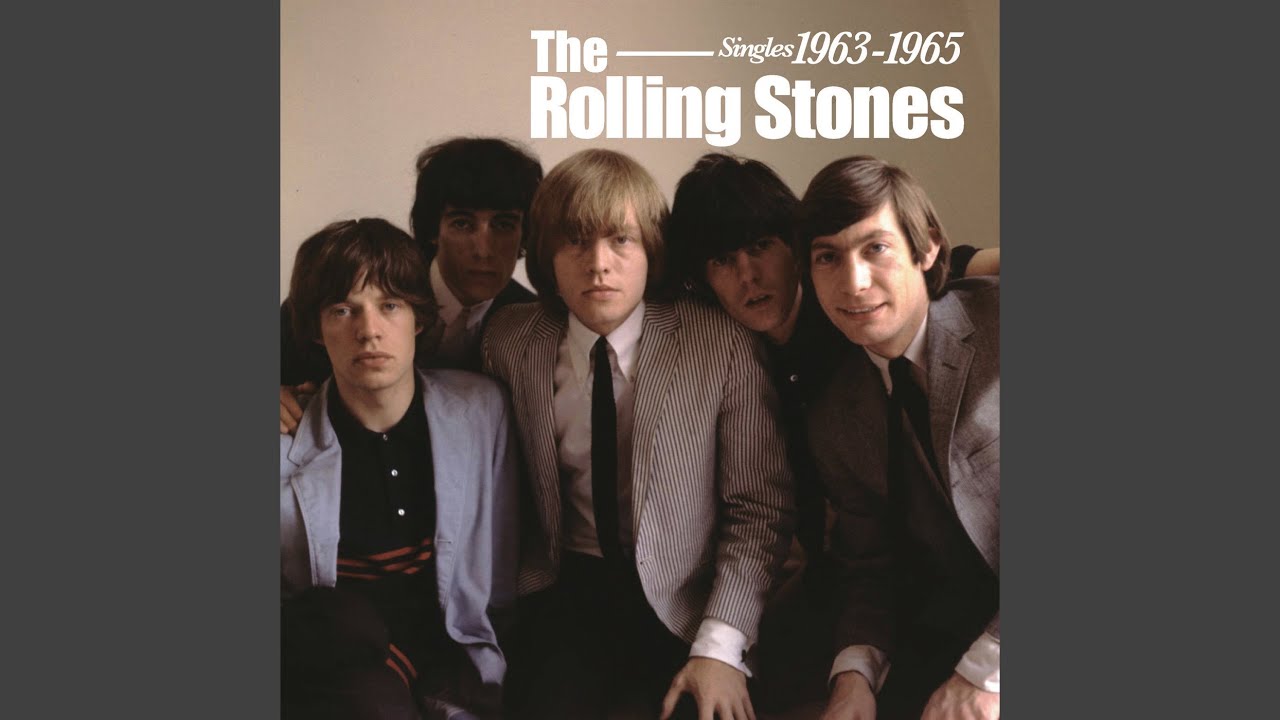

Back to square one, Brian and Stu immediately needed a rhythm section and a singer. And it was Stu who invited Mick Jagger to try out. Jones not only hired Jagger – he also took on his friends Keith Richards and Dick Taylor. Now all they needed was a drummer. They were still relying on temporary help by the time they played their first gig. Mick Avory, soon to join The Kinks, sat in on drums at the London Marquee club on July 12, 1962, where the band appeared under a name hastily coined by Brian: the Rollin’ Stones.

The drummer they all really wanted was Charlie Watts, although he was in a different league. Certainly, he expected to be paid for his services, or to be guaranteed regular work. The fledgling Stones decided to struggle on until they could afford to make him a realistic offer, and so they advertised for a drummer in Melody Maker. The winning candidate was Tony Chapman. He’d been playing in a London rock’n’roll band called The Cliftons alongside bassist Bill Perks, the future Bill Wyman.

The Rollin’ Stones – Brian, Mick, Keith, Stu, Dick and Tony – played once a week at the Ealing Jazz Club in a residency that stretched through to December, taking over from Alexis Korner who’d switched his operation to the Marquee. Other gigs were few and far between. They ventured out to north Cheam for a booking at the Woodstock Hotel on October 5 where, legend has it, they played to two paying punters. In November, they travelled to Sutton, Surrey, for a one-off at the Red Lion pub.

In the early 60s, the live music scene was run sternly by the jazz establishment, which disapproved of the untidy-looking blues and R&B upstarts banging at the doors. Things would change, but for now, it was impossible to find enough gigs to make a living. Come the autumn, Brian Jones made a concerted effort to drum up a decent itinerary.

Brian, Mick and Keith had moved into a £16-a-week first floor flat at 102 Edith Grove, Chelsea. They and various friends occupied two rooms that soon became almost uninhabitable. They were so poor they rarely had any shillings to feed the meter that powered the hot water and the single-bar electric heater. Keith’s mother sent emergency cash and food parcels. It was an icy winter. Sometimes Brian and Keith – both unemployed – stayed in bed all day to beat the freeze, playing guitars under the blankets or listening over and over again to albums by Elmore James, Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and Chuck Berry, at Brian’s insistence.

Jones took his responsibilities as band leader very seriously. He wrote endless letters, promoting the Stones to anyone he thought might be able to help their career. He took charge of the money, such as it was. He was their spokesman and their negotiator. He organised regular rehearsals at the Wetherby Arms, a nearby pub in the King’s Road. And, against the odds, he succeeded in setting up an unprecedented gigging schedule for November and December, booking the band back into the Marquee and into London jazz clubs such as The Flamingo and the Piccadilly as well as out-of-town venues in Hertfordshire, Windsor and Richmond.

October wasn’t the perfect time, then, for Dick Taylor to decide that he wanted to quit music to sit his art exams.

The Rollin’ Stones carried on with a succession of temporary bass players, at the same time auditioning for a new member. Tony Chapman recommended his old Cliftons buddy, Bill Perks, who met Stu first, early in December, and was then invited to audition at the Wetherby Arms.

Bill recalled: “I met Stu again and Mick, who was quite friendly. I was then introduced to Brian and Keith, who were at the bar… they were very cool and distant, showing little interest in knowing me. We brought my equipment in and set it up. Suddenly everyone was interested.”

Perks had a huge bass cabinet and a Vox AC 30 amp. He also had the price of a round, and he had cigarettes to share. After a rehearsal consisting of blues songs by Jimmy Reed and others, Bill played his debut gig with the Stones at the Ricky Tick Club at Windsor’s Star And Garter Hotel on December 14, changing his name to Wyman in January 1963.

This was the month that they again invited Charlie Watts to join the band, and finally got the answer they wanted. By now Watts had left Blues Incorporated to join Blues By Six with Brian Knight and Geoff Bradford – the musicians who’d abandoned Brian Jones’s first line-up of the Stones.

Watts was an accomplished jazz drummer who knew that his musical earnings would plummet by joining this band who were fighting for every gig they could get. But: “I liked their spirit and I was getting very involved with R&B. So I said okay.”

Brian Jones immediately fired Tony Chapman, and Charlie debuted with the Rollin’ Stones on January 12 at the Ealing Jazz Club. At around the same time, Stu bought a van for the band. Now they no longer had to drag their gear around town on buses.

Things were beginning to change on the live circuit. Cyril Davies had taken over Alexis Korner’s Marquee residency, with Korner moving to the Flamingo, and the Stones had started supporting Davies. At the end of January, he sacked them, explaining that, “they are not very authentic and not very good”.

Jazzman Chris Barber told Bill Wyman years later: “We were all a bit highbrow at that time, and the Stones’ attitude to R&B was to us rather poppy. We were a bit snooty about it.”

Wyman later reflected that the “jazz mafia” had it in for the band. But although they lost their Marquee and Flamingo residencies, they hustled extra gigs at the Ealing Jazz Club, they continued at the Ricky Tick and the Red Lion, and they found new venues at the Haringay Jazz Club and the Wooden Bridge Hotel in Guildford, Surrey. But even more exciting opportunities were just around the corner, largely thanks to Brian’s incessant networking.

One night at the Marquee, he was introduced to promoter Giorgio Gomelsky, who ran his own club in the Station Hotel, Richmond. He arranged gigs for the Stones – now spelling Rolling with a “g” – at the hotel (February 24), Studio 51, Ken Colyer’s Soho jazz club (March 3) and Twickenham Eel Pie Island (April 24). These were the places where the Stones began to build both their audiences and their legend.

“You could boil an egg in the atmosphere,” said The Daily Mirror, reporting on one Stones gig at the Richmond club, now named the Crawdaddy, in June, where 500 people were packed into the 100-capacity room to hear the band play Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry and Elmore James.

“The combination of music and sex was something I had never encountered in any other group,” said Andrew Loog Oldham upon seeing the Stones for the first time, at the Crawdaddy. In those days, Brian Jones was the band’s sex symbol, the showman with the shiny blond hair and mysterious glamour.

At the beginning of May 1963, Jones signed the Stones to management and recording deals with Oldham and his partner Eric Easton. Within days, the pair’s Impact Sound had contracted the band to Decca.

Oldham made his presence felt immediately. He announced that Stu didn’t look like a Rolling Stone and must therefore stand down from live performance. Brian proposed an arrangement by which Stewart would continue as the Stones’ roadie and also play on studio recordings, a deal the keyboardist accepted.

Image was very important to Oldham, who also set about switching the focus from Jones to Mick Jagger and building a media profile in which the Stones were pitched as the “bad boy” alternative to The Beatles. Much was made of their rebelliousness, their “ugliness” and long hair.

Their debut single, a cover of Chuck Berry’s Come On, was released in June 1963. It eventually reached Number 21. But the Stones didn’t like it. Mick Jagger called it “shit” and “a hype”. Bill Wyman explained that compared to earlier material they’d recorded, Come On was “pure pop. In truth we would not have got a recording deal if we had carried on with the blues material. We still wanted to play the blues: they were our roots, so we played them live.”

Record Mirror said of the single: “It’s good, catchy, punchy and commercial but it’s not the fanatical R&B sound that their audiences wait hours to hear.”

The Stones had reached the point where they could no longer have it all their own way. Their hearts were in their live shows, and for some time they refused to play Come On. They were, however, thrilled with their next single, the Lennon/McCartney composition I Wanna Be Your Man, a No. 12 hit.

Come On had hurled the band into a whole new world overnight. Their Crawdaddy days were over. In the second half of 1963, they toured theatres and ballrooms the length and breadth of Britain, both headlining and supporting, in Stu’s van. Accordingly, the nature of their material changed. Ditching the deep blues which had been their trademark in the clubs, they developed a vigorous R&B sound that better filled the halls.

In the autumn, the Stones participated in a quaint old 60s institution: the package tour. This couldn’t have been more exciting, because their co-stars were Bo Diddley, Little Richard and the Everly Brothers, whom they regularly upstaged.

Keith later enthused: “What an education – like going to rock’n’roll university.”

And then they were back on the road in their own right until the end of the year and beyond, trying to come to terms with the hysteria of their fans. There were those who simply screamed, fainted and jostled for autographs. There were others who would steal instruments, number plates, anything they could lay their hands on. The Stones got mobbed. Girls ripped at their hair, their clothes, their buttons. Keith Richards soon learned not to wear anything round his neck.

The mania was fanned not only by the band’s primitively exciting and sexual live shows but by their TV appearances. They’d already become regulars on Thank Your Lucky Stars and the endlessly cool Ready Steady Go! The Stones had not set out to be pop stars. They were a rhythm and blues band, whose only mission had been to bring that music to a wider audience and get paid for doing it.

The balance of power was changing. Brian Jones was being sidelined by his own group – and, gallingly, by the managers he’d himself appointed. Andrew Loog Oldham had removed his authority as a decision-maker, and Eric Easton had taken over the finances and the bookings. Jones was now rarely consulted about anything. At the same time, Oldham, Jagger and Richards were forming an increasingly tight alliance, having all moved together into a flat at 33 Mapesbury Road, West Hampstead. They were taking charge.

Oldham saw obvious limitations in the Stones’ policy of playing only covers, and he ordered Mick and Keith to start writing their own songs. Jones, isolated in Windsor with a girlfriend, could only sneer from the sidelines at their earliest efforts.

Throughout 1964, however, The Rolling Stones clung on to their roots. They toured briefly with The Ronettes and extensively with leading lights from the British pop scene, also appearing many times on Top Of The Pops.

Not Fade Away – a Top 3 single in the UK and a breaker in the States at No. 48 in February that year – was an urgently exciting recording, with Jagger’s arrogant vocal riding a sparse but insistent Bo Diddley rhythm, nodding to Buddy Holly along the way. An album followed in April: with breathtaking audacity, The Rolling Stones was released with no name or title on the front sleeve, and it rushed to UK No.1.

Produced by Oldham, it includes a Jagger/Richards song, Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) and two group compositions, Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) and Little By Little, as well as a selection of songs by Willie Dixon, Jimmy Reed, Slim Harpo, Chuck Berry, Rufus Thomas and, of course, Diddley. Route 66, with which they usually opened their live show, and Carol later became set staples for any self-respecting R&B band.

The Stones were satisfied they’d captured their essential sound on the album. Rolling Stone magazine drooled: “This is the hardest rhythm and blues the Stones (or anyone) ever recorded.”

They were met by 500 rabid fans at Kennedy Airport in June 1964, arriving in America for the first time. There they enjoyed the luxury of limos and posh hotels, but other than in New York and San Antonio, Texas, they faced endless rows of empty seats. The highlight of the trip was the chance to record in Chicago’s legendary Chess Studios where they were visited by their own heroes: Willie Dixon, guitarist Buddy Guy, Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters, who said of Brian: “That guitar player ain’t bad.”

It’s All Over Now, a track from the Chess sessions, was released as a single that same month. A UK No.1, it reached No. 26 in the US, and found the Stones exhibiting country qualities in the 12-string guitar and harmonies. All of the band loved it, except for Brian, a strict hardliner.

Back home, touring Britain and Europe, the Stones were playing to crowds of up to 3,000, and there were full-scale riots at tour dates in Blackpool and Le Hague in Holland, with the audiences wrecking the venues. The Daily Mirror fumed: “These performers are a menace to law and order.” From now on, squads of cops were on hand at every gig to protect the band from marauding fans.

After another, better-organised American tour in the autumn, during which they appeared on the renowned Ed Sullivan Show, also recording at LA’s RCA Studios and again at Chess, The Rolling Stones released a cover of Willie Dixon’s Little Red Rooster. It was their purest blues single to date, with Jagger’s sensual drawl and Jones’s exquisite slide guitar creating a lazy, lascivious atmosphere that propelled it to No.1 in November.

They followed that with a chart-topping album, The Rolling Stones No 2, in January 1965. Including tracks recorded in Hollywood and Chicago, it captures an authenticity rare in white bands of the time. Mersey Beat magazine said the Stones were “well into their rootsy, true R&B style, with no concessions made to commercialism or the hit parade”.

In this, it was something of a “last hurrah”. As they toured Australia, New Zealand and Singapore in January and February 1965, Mick and Keith were about to give the band a No.1 single with one of their own compositions. The Last Time was poppier, rockier than anything the Stones had done before. With Satisfaction and Get Off Of My Cloud bringing up the rear, and the Stones investing their R&B blueprint with influences from soul and pop, they were well on the way to rock’n’roll world domination.

Jagger & Richards were making good their silent pledge on the train to Sidcup. For blues angel Brian Jones, disappearing into a drink and drugs-induced oblivion, the dream was over, bar the shouting.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Cream And The Story Of British Blues Rock, April 2007