Ronald Frederick Lane was a star but he never took his stardom that seriously. “I like showing off, doing a song and shaking a leg on stage, but I don’t want to play all those silly games that go on, any more,” he said in 1975. Sixties rock icons, of which he was one, didn’t float his boat: “As far as I’m concerned, if half of them had never been stars they would have done something better; it’s totally stardom that’s fucked them up. Or this illusion of stardom – it’s not even real. Alright, let the little girls’ magazines say it’s glamorous and all that, but Christ, we’re grown men aren’t we? We should know better. But no. All the ‘stars’ think it’s glamorous too…”

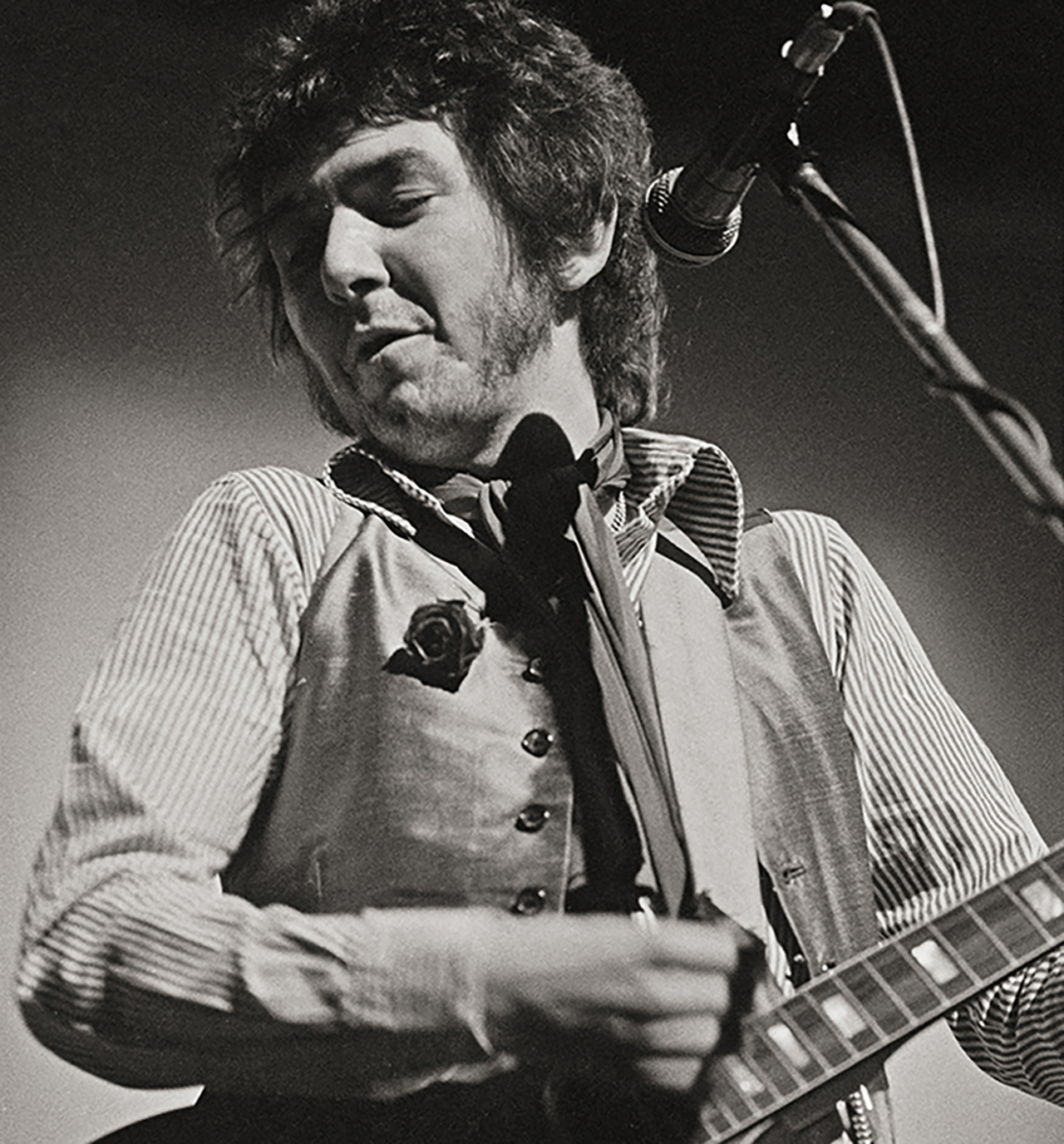

He was a man of his word. Two years earlier, Ronnie had walked away from his gig as the bassist with The Faces, the boozin’, carousin’ reprobates who had risen from the ashes of his earlier band, the Small Faces. But the man who his old muckers called both ‘Plonk’ and ‘Three-Piece’ didn’t just quit his band – he quit the rock’n’roll world, upping sticks and moving to a rundown farmhouse on the Welsh borders, where he put together a new band, Slim Chance, and lived out his gypsy dreams.

“Ronnie really dropped out,” says bassist Steve Bingham, who played in the original Slim Chance and is part of the line-up that re-formed in 2010 and still plays today. “Him and his wife, Kate, embraced the whole cosmic gypsy look. What a mischievous geezer and wind-up merchant he was.”

It was his old mate, Ian McLagan who nailed Ronnie Lane. “Short and sweet was our Ron,” said McLagan, who played with Lane in the Small Faces/Faces. “He loved a joke. He used to cry with laughter. He had that real cockney knees-up attitude. He didn’t know the meaning of ‘pretentious’.”

But Lane had raised eyebrows in the Small Faces when he developed a voguish interest in Eastern religion. Funny, weird little Ronnie set up a shrine in his dressing room, complete with a hippie scroll and a peach cut into quarters, around which he burned incense. The others weren’t impressed. “When we saw him, we ate the peach and burnt the scroll,” said Small Faces singer Steve Marriott. ‘Cor blimey, Mrs Jones, ’ow’s your Bert’s lumbago’ was what the Small Faces wanted. Not this oddness. Ronnie bit his lip but he didn’t button his attitude. He marched to his own beat and no one else’s.

He was still marching to his own beat on June 6, 1973, when The Faces played the Sundown Theatre in Edmonton, North London. As their customary encore of We’ll Meet Again drew to a close, few outside the band and their nearest’n’dearest knew it was Ronnie Lane’s last show with the old gang. Watching footage of the show now, everything seems hunky dory until you notice the if-looks-could-kill glances aimed at Rod Stewart’s back by the embittered bass player during Jealous Guy.

Ronnie’s hostility towards the singer had been building until it reached boiling point. Stewart – or “that c**t Rod”, as he habitually called his bandmate – had not only usurped the rest of the group and turned them into his glorified backing band, but he’d also bad-mouthed their most recent album, Ooh La La, in the press. “A stinking rotten album,” was Rod’s assessment, though his absence from half the sessions hardly gave him much authority. The bassist, who had written the entire second side of the record (including the title track, which had only been green-lit by Stewart after insisting guitarist Ronnie Wood sing it, as Rod couldn’t find the key and didn’t like Lane’s rendition), was livid. He couldn’t wait, he said, “to fuck off”.

Matters came to a head during the Faces’ 1973 US tour. On May 10, after a gig in Nassau County, Ronnie told the others he was leaving. The tour ended the following night with an onstage riot after Lane swore viciously at Ian McLagan, who responded by throwing a drink at his bandmate’s head and aiming a kick at his nuts. A month later, after the gig in Edmonton, Ronnie was gone. No tears were shed, no party was thrown for ‘Three-Piece’. More a case of goodbye and good riddance.

“Ronnie had it with all the cocaine, champagne and the private jets,” says the Faces’ tour manager Russell Schlagbaum, who was on the road with them in the States when it all fell apart. “He started travelling with his wife, Kate, and he brought the family, which was a no-no. The rule of the road was ‘no girlfriends’. Do all the drugs and fuck all the groupies you like, then get back to normal in England. Here were Ron and Kate carrying a child in a wicker basket, making no eye contact with the others. Everyone’s thinking: ‘What’s happened to Ronnie Lane?’ He was dressed like a gypsy with earrings and shabby clothes.”

At the time, Faces drummer Kenney Jones recalled Ronnie and Kate as “this grubby, dirty-looking couple. And we started seeing a lot of Kate. Too much.”

The Small Faces’ mod gear had long been confined to the wardrobe, replaced by tweeds and battered boots. Modernist chic became Celtic hillbilly. But Ronnie always had a tinker’s soul. His folksy, vulnerable side showed in songs such as Devotion, Stone and Flags And Banners. Although his undeniable masterpiece was Debris, from the Faces’ A Nod’s As Good As A Wink… To A Blind Horse. Sung in Plaistow vernacular, it was a portrait of his dad, Stan Lane, laid off from his job as a long‑distance lorry driver, sifting through the ‘odds and ends’ at an East End Sunday market.

“Debris is about my old man,” Ronnie explained. “The Debris was down… not Petticoat Lane, which is famous, everybody knows about it, but an adjoining market called Club Row. People came out there with all their chuck-outs and flotsam and jetsam and spread it out on the Debris. Every Sunday morning, he’d take me down there and he’d root around for hours in all this shit. It wasn’t until I was in New York that I realised I missed it. I was feeling homesick at the time.”

By the time Ronnie was back in Blighty and out of the Faces, he made up his mind: fuck ’em all. In the summer of 1973, he and Kate – his second wife, whom he’d met in 1972 while she was married to Mike McInnerney, sleeve artist for The Who’s Tommy – bought a 110-acre farm, Fishpool, near Hyssington on the border of Shropshire and Montgomeryshire.

The couple renovated the derelict cottage and turned the barn into a rehearsal space. The East End it was not, yet Ronnie felt at home. For one thing, it was miles from the nearest coke dealer. For another, Ronnie and his friends could smoke dope with impunity before moseying into the village to pick up crates of Barley Wine from the boozer. Parked outside the main cottage was his Airstream trailer, which he turned into a 16-track mobile studio – a cash cow when leased to the likes of The Who, Eric Clapton and Bad Company.

The move to this rural idyll was Kate’s idea. She kept a cauldron of soup going on the stove and washed Ronnie’s favourite silk suits in boiling water before, literally, mangling them. “Ronnie followed me to Wales after we sold Wick Cottage [in Richmond] back to Ron Wood,” Kate says today, from her home in Wales. “We did a runner because the shit hit the fan when he left The Faces. We wanted to live on the road and we’d already travelled around Ireland in a Land Rover with [singer-songwriter] Billy Nicholls, singing in pubs. The farm was a different way of life.

“Was Ronnie hands-on? Ha ha! When he remembered. He liked the concept, but doing a hard day’s labour was a little exhausting for the poor love, though later he went to Newtown and did some classes at agricultural college.” (“I dunno if I can hack this, Kate. I got 15-year-old farm boys flicking rubbers at me,” was her husband’s assessment of his time at college.)

Ronnie had worked with other musicians during his time in The Faces, contributing to Pete Townshend solo album, 1970’s Happy Birthday, and the 1972 Townshend collaboration I Am (the two shared an interest in Eastern religion, and both albums were dedicated to Townshend’s spiritual guru, Meher Baba). He’d also worked with Ronnie Wood and producer Glyn Johns on the soundtrack album Mahoney’s Last Stand in Ooh La La downtime (the record would eventually emerge in 1976, four years after the film itself).

But now it was time to put together his own thing. Lane invited a raggle-taggle bunch of musicians to the farm: Irish guitarist Kevin Westlake, guitar/mandolin player Steve Simpson, bassist Steve Bingham and the Scottish duo Benny Gallagher and Graham Lyle, formerly of pub-folk outfit McGuinness Flint.

“‘Bring your mandolin,’ he told me on the phone,” recalls Gallagher. “Staying in Fishpool was lairy because I had two sets of twins – the caravans all leaked but it was great to wake up and go to the barn for recording.”

Lane called the group Slim Chance, a name had that been knocking around since the Small Faces split (Lane suggested that The Faces’ debut album First Step be credited to Fat Chance or No Chance, both of which were deemed too negative). Their magnificent first step was the Dylan-meets-George Harrison-esque single How Come. It made No.11 in the UK charts in January 1974. Not Maggie May, but good enough.

“There was a sort of formal democracy but Ronnie was in charge,” says Steve Simpson now. “Organic but with direction. He’d come into the barn with his lyric books, which he kept very private – we weren’t allowed near them – and we created the songs in a lateral fashion. It was completely rustic. Locals and friends would wander in and it felt more like a gypsy camp than a hippie commune.”This air of anything goes fed into their debut album, Anymore For Anymore (credited as a Ronnie Lane LP, though he was backed by Slim Chance). Ronnie had recorded a version of the title track with The Faces in 1972; when Rod Stewart heard it, he’d sniffed: “Who wrote this tripe?” Elsewhere, the album conjured up a transcendental image of the English countryside. On the single The Poacher violinist Ken Slaven and saxophonist Jimmy Jewell melted into Jimmy Horowitz’s glorious string arrangement. It was British pastoralism taken to another dimension.

“Ronnie’s strength was putting human melody and storyline together,” says Benny Gallagher. “His phrasing was unique; he was one of the most underrated singers in the UK. The scene was quietly crazy. He even had his builders, the Tanner brothers, and their families singing on the album. You can hear the chickens in the background and the noise of children.”

Not everyone was so enamoured with the set‑up. Jimmy Jewell played on both How Come and Anymore For Anymore. “The farm had a swamp at the back that was being excavated,” says Jewell. “I think he’d been ripped off by the vendors cos he was pleading poverty, but there were piles of cash lying around, US and Aussie dollars and yen.” Nor was Jewell enamoured of Lane’s new lifestyle: “I thought Lane was playing at being a gypsy which was most odd, and I also don’t think he respected me as a musician.” (In fact Ronnie described Jimmy as a magnificent saxophonist – they fell out later).

Anymore For Anymore was released in July 1974. The sleeve featured an atmospheric silhouette of a pair of travellers on a horse and cart against a golden sunset. Ronnie wanted to advertise the album in Exchange And Mart. If anyone was still unsure as to where Ronnie’s head was at, here was all you needed to know.

But while the bonhomie might have been tangible, the public weren’t buying it. Anymore For Anymore bombed, scraping into the Top 50 for one week. But that was the least of their worries.

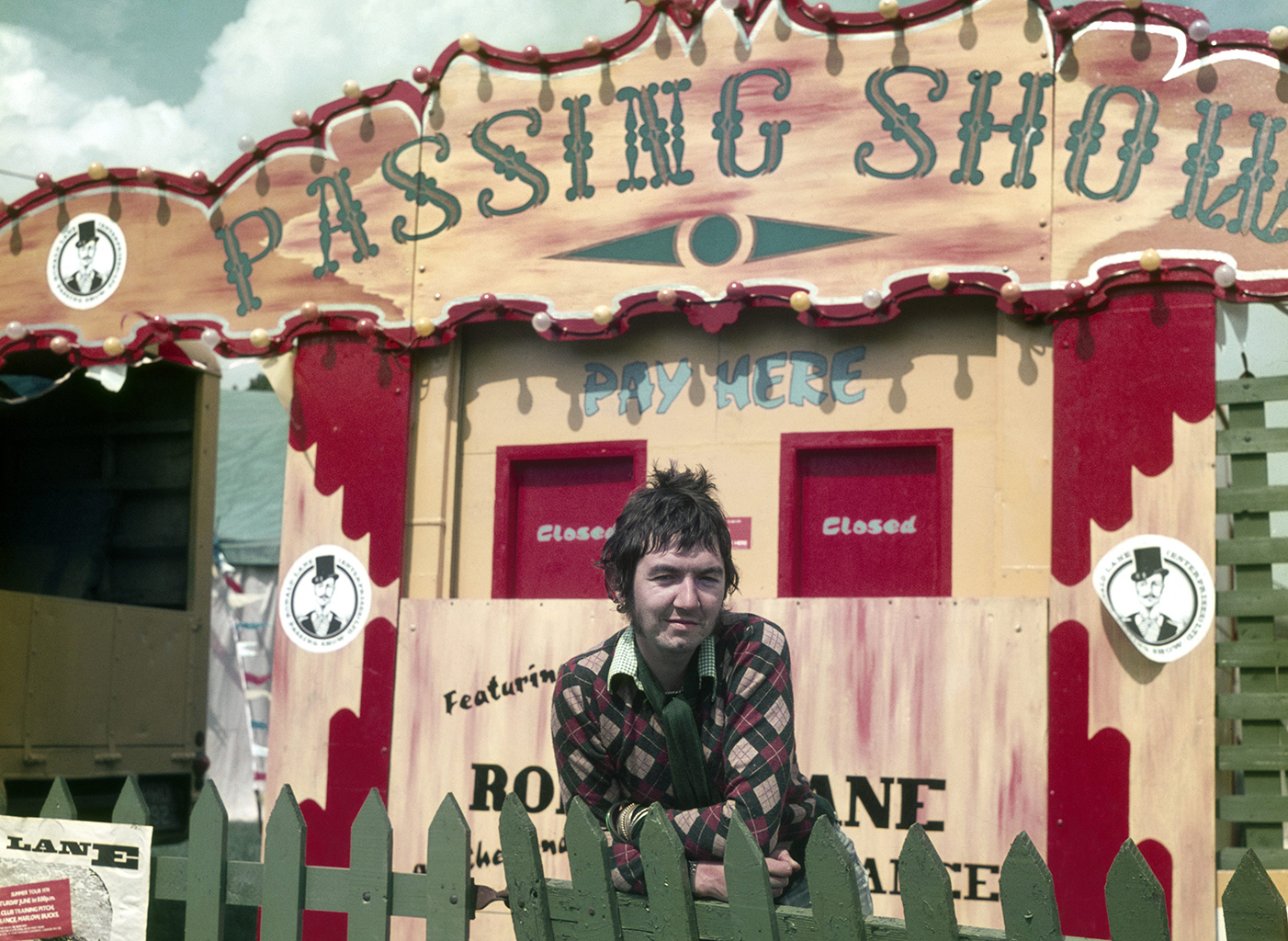

Lane had publicly unveiled Slim Chance on November 11, 1973 – Armistice Day – on Clapham Common, South London, in a Chipperfield’s Circus tent. Enthused by the chaos, he decided to take his own version on the road. It would be called The Passing Show. Ronnie was euphoric. “It’ll be more carnival than circus,” he enthused. “The audience will come because it’s music, and there won’t be any animals or trapeze acts. But we’ll have dancing girls and a good comedian/compere. We’re now in the process of buying a load of old single-decker London Transport buses, cos they’re in good nick. We’ll put bunks in and turn them into box offices.”

It was a grand idea that fitted in with Ronnie’s Romany-esque vision of life. But while it looked good on paper, the reality was very different.

The Passing Show premiered in Marlow, Buckinghamshire in June 1974, on the local football team’s training pitch. The show went well, but there were complaints from local residents. The buses Russell Schlagbaum had bought from London Transport for the tour turned out to have been stored behind the sheds at their Acton depot. Far from being “in good nick”, they could barely negotiate Britain’s rural byways, and most of them fell apart on the motorway.

This travelling circus had the gypsy spirit. Its caravans and rickety buses were home to the band and assorted professional circus performers, as well as Captain Peter Hill, an authentic traveller hired by Ronnie.

“He knew everything about the circus so he was in charge of the clowns – whom the band hated because they were so useless – the fire-eaters and the dancing girls,” says bassist Steve Bingham. “On the road most of the vehicles broke down. The caravans were so rickety we only travelled at 20mph and we were constantly pulled over by the police and harassed by the council. But Ronnie would produce a bottle, fill ’em up and it would eventually be fine.”

Ronnie and Kate were in their element. “We were on the Chicken Shit Express, all very nostalgic. I organised the can-can girls – me, Russell [Schlagbaum]’s girlfriend Barbara and Josie Livsey, the wife of our American keyboard player Billy. I got us costumes from Sotheby’s so we looked like a cross between those girls in Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec paintings: the card up the sleeve. The audiences loved us and the level went up once we arrived for Ooh La La and Ain’t No Lady.”

Some people got into the spirit of things a bit too much. Former Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band leader Viv Stanshall was hired as master of ceremonies, but was asked to leave after drunkenly pouring drinks into the amplifiers and breaking Ken Slaven’s violin at the first show. The final straw came when Stanshall was found in guitarist Kevin Westlake’s caravan, glass in hand, trousers round ankles, asking: “Got any toilet paper, old bean?”

But the high jinks masked the fact that The Passing Show was losing money hand over fist. A stop-off in Newcastle drew barely 50 people across three shows. At Chester Racecourse, there were more people in the circus than in the crowd.

Jimmy Jewell has less-than-rose tinted memories of the tour. “It was a great idea but the figures didn’t add up,” he says. “We got pissed a lot. He’d buy us bottles of Blue Nun – horrible stuff – where it was Guinness, Barley Wine and a bottle of Courvoisier for Ronnie. I got fed up because I was dragging my wife and child in a broken-down caravan and getting paid thirty quid a week. Nuts. Cost me more in petrol. I asked for a pay rise. He said no. So I said, ‘Enough.’ I left a note on his door – ‘Goodbye cruel circus, I am off to join the world.’”

“Of course it went tits up, but I was glad it did,” says Kate now. “Added to the fun. It lost a lot of money though, which scarred Ronnie cos this was his dream.”

For Lane, The Passing Show was a success purely because it happened. “Some people didn’t like The Passing Show because it just wasn’t heavy enough for them – but I’m not into that anyway,” he said. “I’ve been all through that heavy stuff. It just doesn’t exist. It’s a total illusion that some people live under. What I can do is for people. That might sound incredibly pretentious and it does, but I happen to mean it. I don’t want anything. All I want out of it is a life. Something well spent. That’s all I want.”

After The Passing Show limped to a halt, Ronnie retreated back to Fishpool, where he bought sheep and planted barley. Slim Chance made two more albums, 1975’s Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance and the following year’s One For The Road.

“Slim Chance didn’t even get reviewed and One For The Road did terribly,” says multi-instrumentalist Charlie Hart, who played on both records and lived at Fishpool for two years.“But that wasn’t the point. Ronnie was ahead of his time. Unplugged before anyone else. And he kept that Small Faces’ sense of humour and knew how to harness creative energies.”

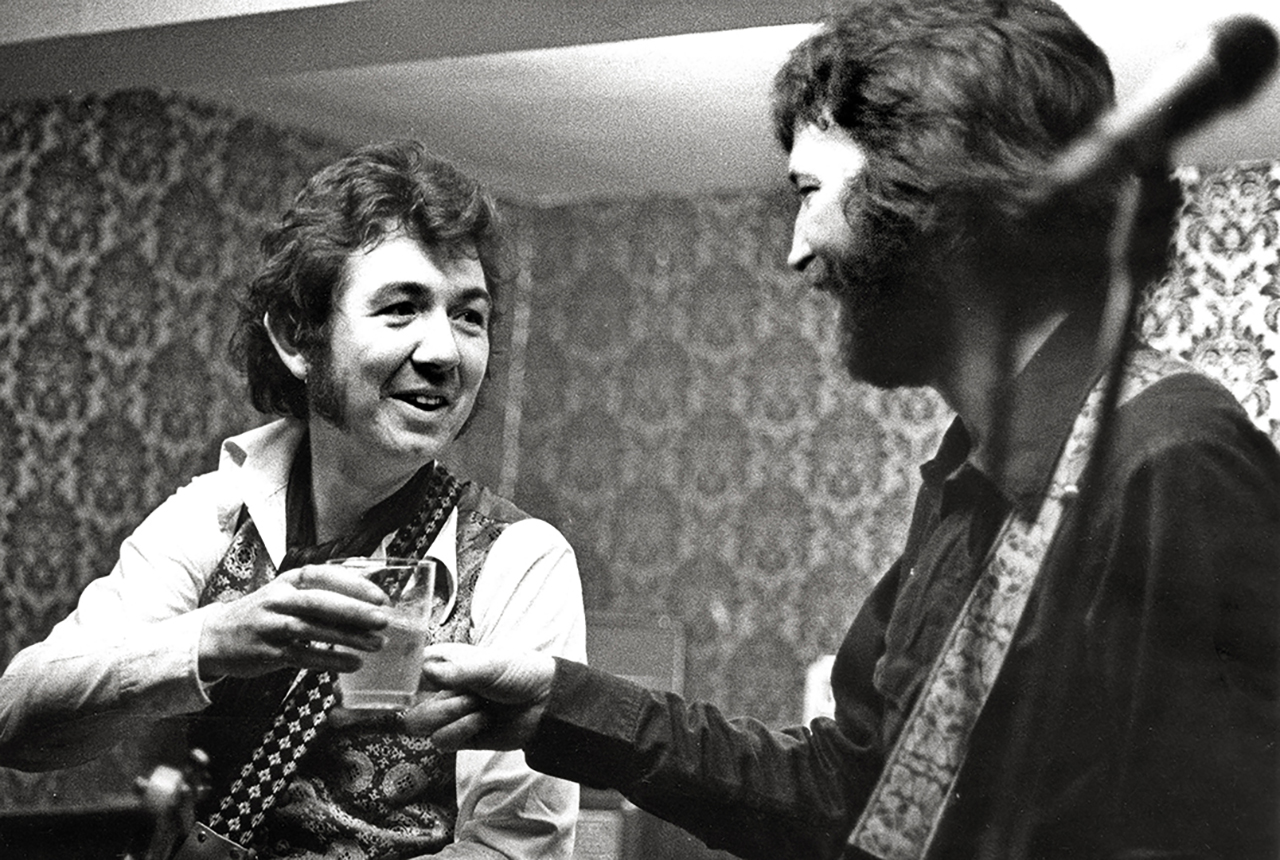

There were impromptu gigs in local pubs such as The More Arms, The Drum And Monkey and The Miner’s Arms. Old pals such as Alexis Korner and Eric Clapton would drop by. “Eric wrote Wonderful Tonight at ours, sitting on a wheelbarrow,” says Kate. Clapton recorded the song on the spot in Ronnie’s Airstream trailer studio.

Lane’s spirits were high, but his finances were in disarray. “His books were a shambles,” says Russell Schlagbaum. “There was money, he was far from broke. But nobody knew where it was. Some of it was in Jersey, but not even Barclays [Bank] in Montgomery could make sense of his accounts.”

With creditors knocking on the door, Lane reluctantly agreed to a Small Faces reunion in 1977, after Ian McLagan and Kenney Jones visited him in Wales. Ronnie attended one rehearsal, got horribly drunk and abusive, and stormed off.

What no one knew was that he was starting to show symptoms of multiple sclerosis. His mother Elsie had suffered from the disease, and Ronnie still remembered how he and Kenney Jones used to carry her down the stairs of their flat in Plaistow. It was a painful memory, and Lane feared he would inherit the illness.

His friends, meanwhile, had no idea what was going on. Pete Townshend, who collaborated with Ronnie on 1977’s ambitious Rough Mix album, was baffled by his friend’s behaviour. “I thought he was drunk,” said the Who guitarist. “He was slurring his words, yet he hadn’t had a drink.”

Russell Schlagbaum had noticed a change a year earlier. “Ronnie couldn’t always hold a plectrum,” he says. “I thought it was the after-effects of too much Barley Wine or cocaine. It wasn’t. It was the onset of MS. He refused to admit it because his mother had the disease and he was petrified.”

One For The Road was the end of Slim Chance, although Ronnie did make a final album, 1979’s See Me, with some of the old crew. By that point he’d gone public with his MS diagnosis (he lived with it until he died in 1997). He’d also left Kate.

“You can’t keep a horse locked up,” she says. “When he left he told me, ‘I loved you cos you’re all woman, but you think like a man.’”

Oh, that restless spirit. With the smell of The Passing Show still in his nostrils, Ronnie Lane gazed into his crystal ball and told his own fortune two years earlier. “I can’t see me settling down to living in a house. Nah, I like to be a stranger. It’s easier, see. You pass through things… there’s this cluttering up business whenever you settle.”

He wouldn’t be doing that. No chance.