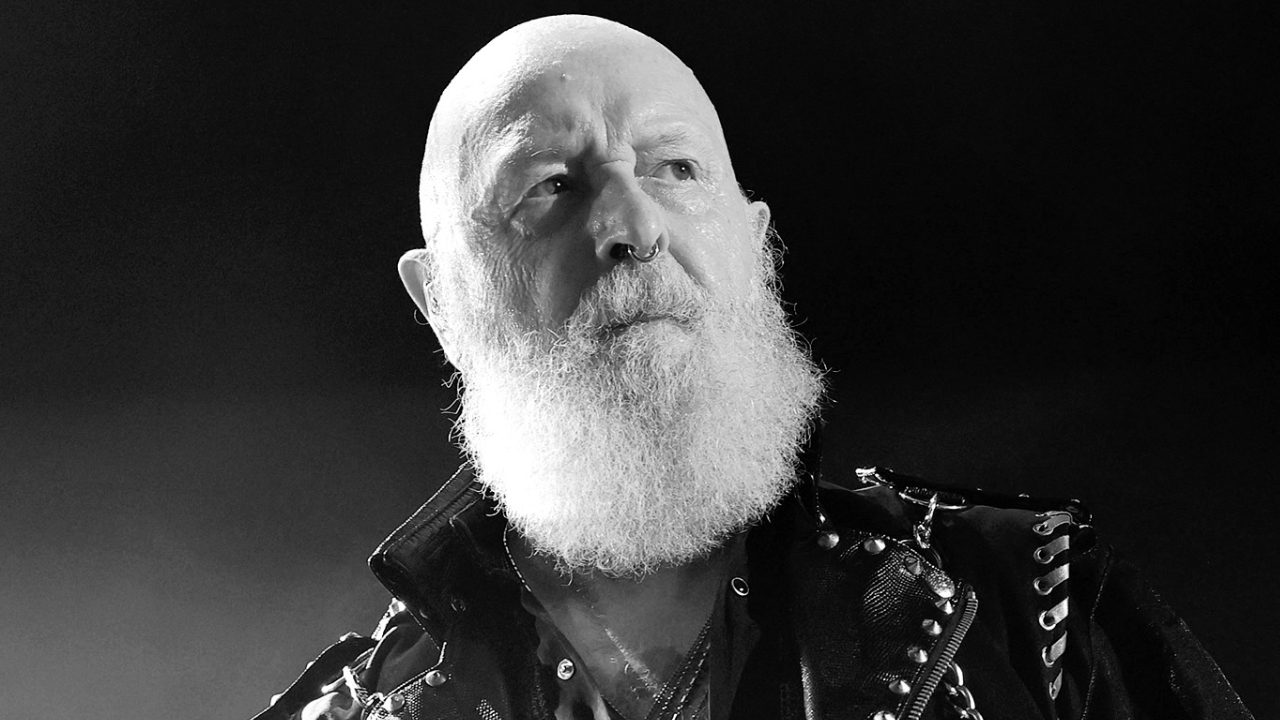

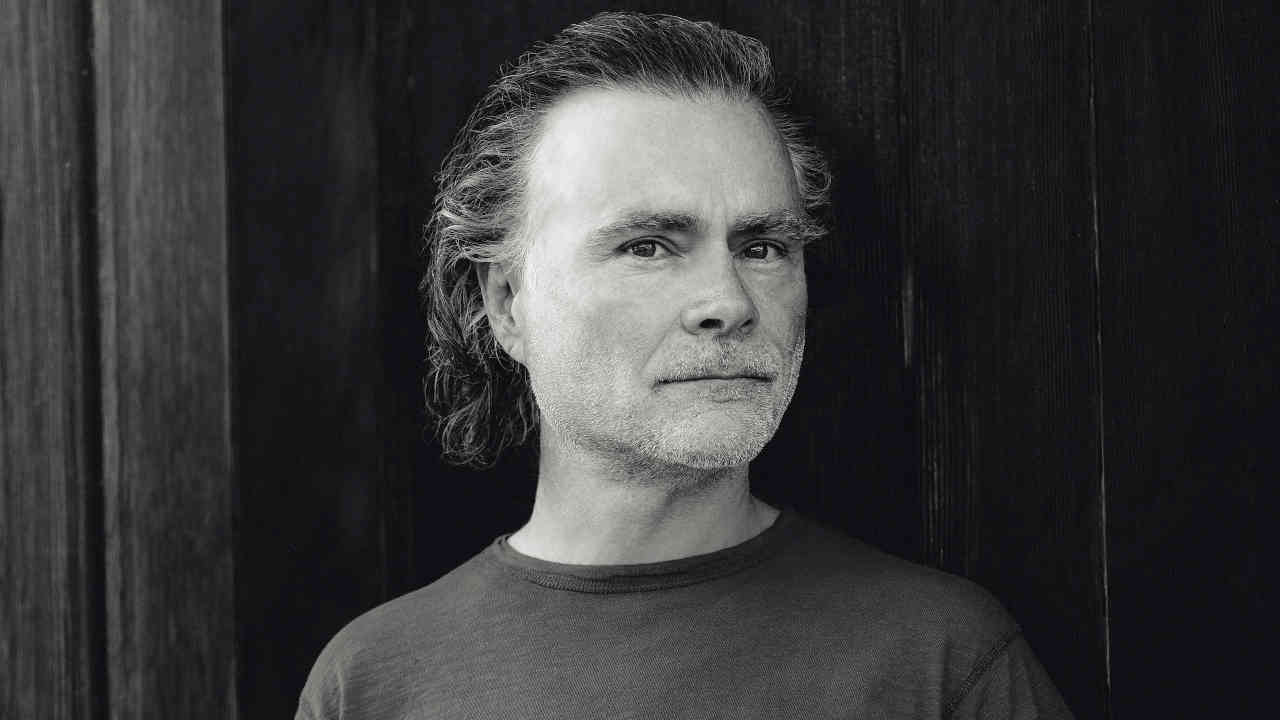

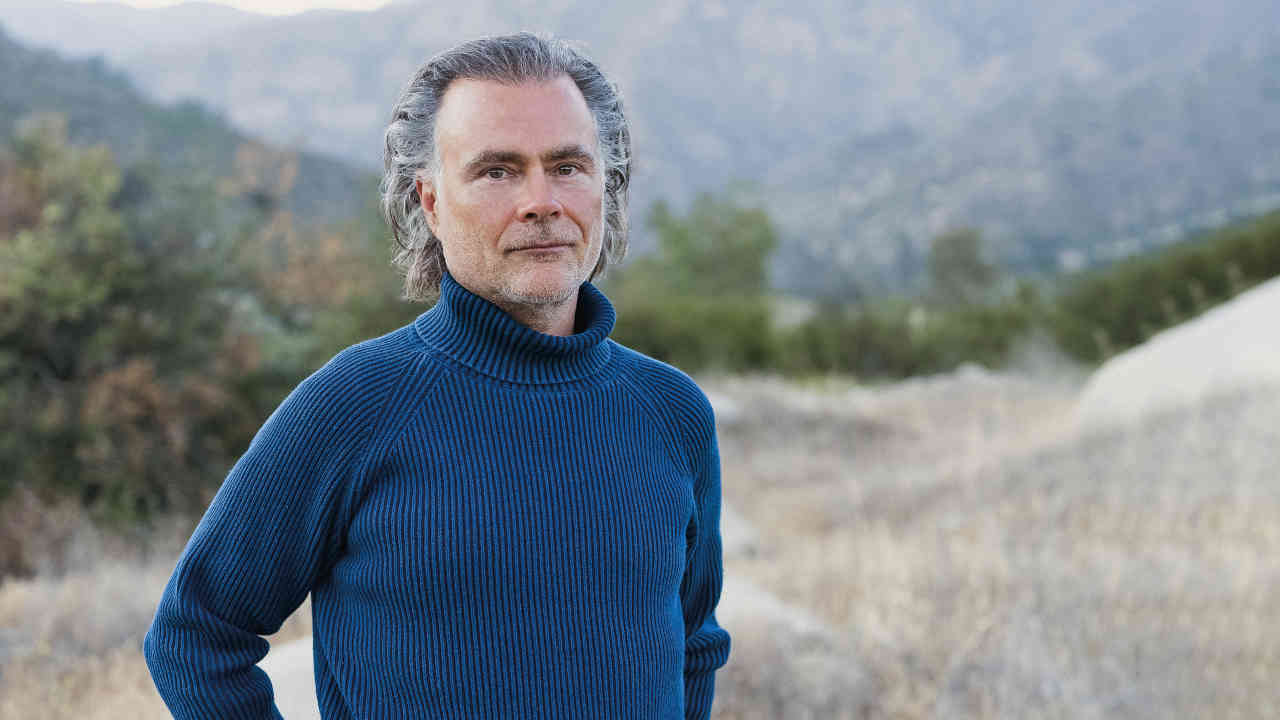

“Fred Durst is the most charming person I know”: how super-producer Ross Robinson defined an era

From pushing Korn and Slipknot to the edge to his turbulent relationship with the nu metal scene he helped create, this is producer Ross Robinson’s rollercoaster life story

As the producer of Korn, Limp Bizkit and Slipknot’s debut albums, Ross Robinson defined what would come to be known as nu metal, wringing emotionally and sonically heavy performances out of the bands. He had discovered music at age six, and says he and his younger sister would sit around drinking wine and listening to his uncle’s Led Zeppelin record.

“We’d play Black Dog over and over and over. I remember doing this a lot – the same record, wine and feeling this insane, incredible, mystic thing of partying with my sister, ha ha ha!” he recalls. “Where were our parents? It was the 70s, do I have to say more?”

That interest snowballed, leading to his bands Détente and Murdercar, and a stint working at the studio of W.A.S.P.’s Blackie Lawless. But it was Korn’s 1994 self-titled first record that lit the fuse on his career. Using skills learned from workshops run by his mother, Byron Katie, who devised a method of therapy called ‘The Work’, he helped them access their deepest feelings. He’s produced Machine Head, Sepultura, Glassjaw, At The Drive-In, Suicide Silence and more, and still works with heavy bands today. This is his story. Are… you… ready?

You were born in 1967. What’s your earliest memory?

“Looking in the mirror, and seeing my face for the first time, and just staring at it and thinking, ‘I’m not supposed to look like that, not me.’ Ha ha ha! Everybody thought I was the cutest kid ever, but it didn’t make sense, so that was pretty heavy.”

Yeah, why did you feel that way?

“I think because when you’re attaching yourself, your memory has to start somewhere. There was no prior story to what I looked like, so it was a brand new experience that I couldn’t attach to. So the first time I saw my face, it had no reference.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What was your home life like in Needles, California?

“Around age seven, I got a dirt bike, and I was allowed to take off into the open desert. My mom used to hand me a book of matches and say, ‘If you get hurt, or need help, light a fire and we’ll find you,’ ha ha ha! So, I’d just take off, and I’d run out of gas out there and struggle pushing my bike back home.

“On the Colorado River, there were boats and frogs and fish and wildlife and the smell of the water, and my parents started a contracting business the year I was born, and it was thriving. So, there was this thing where we were semi-big fish in a pond, and I had this really amazing sense of self- worth and wellbeing and connection to nature and all of that; it was spectacular. But my parents fought, and my mom took us away, and I didn’t like that. We moved to Vegas when I was in the third grade, and I was super-, super-resistant. Our dog disappeared and died in the desert somewhere.”

How did you cope in the long run?

“Basically, my ‘ism’ is an eating disorder and self-image, and that relates back to the mirror thing. So it is a good drug of choice, because I chose sprouts and wheatgrass and health and, ‘Don’t I look great? Aren’t I a great person because of what I eat?’ – a vegan in the late 80s, early 90s, it was really extreme. The eating disorder took over my life, and during Korn rehearsals, through all the demos, auditioning Jonathan, and that whole thing right before they were signed, was when I had my deep, deep spiritual awakening.”

When did you start playing music?

“My mum married and my stepdad was a construction worker, and he was retired and he loved taking us to the races. So my whole identity was all motocross, motocross, motocross – it was all I cared about, it was all I thought about, and I got hurt really bad, gashed out my leg, and they said it was 400 stitches to repair it. Then I started racing again and I broke my leg, and my mom was like, ‘That’s it!’ Ha ha! The doctor told me my leg wasn’t gonna grow, but luckily it did.

“Missing my dirtbike, I had a dream about a guitar. It was just as cool, and I became obsessed with it, and started taking lessons. I was going to go to an Ozzy concert, and Randy Rhoads died [in March 1982] two weeks before I was gonna see him.”

You used to play in the bands Détente and Murdercar. What made you realise that production was for you instead of playing?

“In Détente, we had a record producer, Dana Strum. He was the bass player and producer of Slaughter, and he was my next-door neighbour’s boyfriend. Détente got a record deal with Roadrunner, who were only in Europe at the time, and they licensed us to Metal Blade in the US. So, Dana produced the record [1986’s Recognize No Authority]. I started working for him after, and I fell in love with the studio; it was like, ‘Oh my God.’ Not only do you get to be in the band you’re in, you get to be in all these other bands.”

The first record you produced was Fear Factory’s Concrete in 1991, but then they re-recorded it. Was that disappointing for you?

“It was absolutely crushing, and it was probably one of the catalysts for falling into the depths of the eating disorder, because I had so much hatred inside of me for those guys. It was absolutely ‘How could they?’”

Your mum, Byron Katie, referred herself to a counselling centre when you were 19, and then became a self-help author. What impact did that have on you?

“Well, before we did the first Korn record, to survive, I would go help her with her early workshops, and I was in charge of the cleanses. So I would give people psyllium and bentonite and their herbs, green algae, and she did ‘The Work’ with them. And that was in a place called Tecopa, California, near Death Valley. It’s a hot spring that they say is the third most healing waters on the planet.”

How have her motivational teachings impacted you?

“I was one person before doing these workshops with her, and we were doing Korn rehearsals – it was the demo stage, where they were on to people coming to the shows, and things were heating up a little bit – and I remember [guitarist] Brian ‘Head’ Welch from Korn told me this awesome line. I said, ‘OK, I gotta go do a nine-day workshop,’ and he goes, ‘Oh, man, don’t come back all weird again!’ Ha ha ha! I kept coming back all weird, so it allowed me to see my character defects and allowed me to see where I’m in the wrong, and it allowed me to become a record producer that goes for the heart.”

What happened to you at the workshops?

“One example was this person was honking and honking and honking, and I was getting cash out of a cash machine, and I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s interesting.’ And I’m feeling connected, and really aware, and this guy gets out of the truck, and he’s like, ‘Who’s the fucking asshole who parked here like that?’ And I turned around, and I go, ‘Oh, that was me.’ He goes, ‘Well, you’re an asshole.’ He thought I was gonna fight him, and I go, ‘I care about you so much and I want you to have a great day’, and gave him this massive hug. That’s the difference between before the workshops and after. It gave me a true courage to be able to face the heart rather than the obvious war.”

What state of mind were you in when you were working on that first Korn record in 1994?

“My tool was to go into the bathroom at Indigo Ranch [Studios in Malibu], put my head on the floor and ask nothingness for help, and I didn’t know what God was or anything like that. ‘I don’t know what I’m doing, whatever it is, I’m here for whatever’s supposed to be, please help.’ And then I would stay until my body was overwhelmed with those chills, and it’d be like [sharply inhales]. I’d walk out and answers came. It gave me a sense of eternal knowing that wasn’t tapped into before. The main thing was love; love for them, love for myself, self-nurturing.”

The song Daddy is so emotional. How did you get Jonathan to deliver that performance?

“I just went up to him and held his arms, looked straight in his eyes and said, ‘You need to do it,’ and he goes, ‘I know,’ and that was it. And I still, to this day, haven’t been able to get that deep of a performance from anybody. His heart was exploding, and I think we made musical history.”

Did it feel groundbreaking to have that kind of raw emotion in metal?

“Yeah, and you have to remember, too, I was in these workshops where the norm was people talking about losing their children, divorce, cancer, death. I was in that forbidden zone space with people that were in their 40s and 50s, cleaning out their garbage and their lives and their heads and their souls, so it was like, ‘Yes.’ Sometimes, my mom will play that song in her workshops. It blows people’s heads off, crazy.”

You also worked with Limp Bizkit. What was Fred Durst like in 1997?

“He’s probably the most charming person I’ve ever met. When Korn went through Jacksonville, Fred got my number, my address, and he sent me a cassette. I called up Fieldy, like, ‘Dude, why’d you give that guy my number? He keeps leaving me messages.’ I was really annoyed with it, and then my girlfriend listened to it and she goes, ‘This is really good.’ And I listen to it, and I remember like, ‘Oh my God, this is really good.’ And so I gave it to my manager, and we got it a record deal instantly.

“Fred, being the entrepreneur, convinced us it wasn’t good enough yet, got out of that record deal, and got another record deal. And then during the album, he wanted to be on Interscope, so the guy who did the deal before Interscope had to do a deal with Interscope. So he’s like a mega-businessman and just a kid.”

You were with Slipknot from the first record in 1999. How did you react when you heard them for the first time?

“The first demo I didn’t really like and it kind of sat there. Then, their acting manager, at the time, worked at a radio station in Iowa. She was a programmer, and she only knew one person in LA to try to get it signed, and she goes, ‘Do you know how to get a hold of Ross Robinson?’ And he goes, ‘I do, because I manage him.’

“We flew out to Iowa straight away and we go to Clown’s house. They’re rehearsing and they didn’t have masks on. I remember Corey’s face, so fucking animated and awesome.

“They played the next night, and [at first] I was like, ‘Oh, man, the mask is not relating like it was in the rehearsal room. His eyes and his face were so cool, this isn’t as good.’ [But] with the masks, the performance was fucking insane; people were just killin’ each other inside the club, and the smile on my face was indescribable. I think the masks allowed ’em to become something other than their egoic self; they were able to let all of their identity go and become something else that they couldn’t be otherwise.”

How integrated into Slipknot were you back then? Did they see you as a friend or as an outsider?

“Well, after that show, we all hung out and fell in love and were inseparable. They were my response to everything that was just blowing up. I think [Limp Bizkit’s] Nookie was out and Korn had massive success without me, and I wasn’t a part of that; I was kind of pushed out, for some reason. So, I was like, ‘This is what I feel like,’ and they were like, ‘That’s what we feel like, too.’ They knew what they were, and I knew what they were, and it was something to wipe the slate clean and start over, and ‘Here it comes, here comes the pain’, ha ha ha!”

On tour, people talked about how Clown liked shitting onstage, and they had a jar for vomiting – did any of that make it into the studio?

“No, zero. That’s a lot of free time on your hands, on the road, and boredom. For us, we were slamming, slamming, slamming. There was a time where skunks were coming around Indigo, ’cos it was up in the mountains in Malibu, and I told Mick [Thomson, guitar], ‘Dude, if you catch one of those skunks, and give it a death growl right in its face, I’ll give you two hundred bucks.’ He stripped all the way down to his black bikini briefs, he looked like [something out of] Metalocalypse, looking for this skunk underneath a trailer that they’d hang out in, but he never got it. He turned out OK, he got plenty of money! Ha ha ha!”

You do have a reputation for pushing people’s emotional buttons. Have you ever worried that you’ve gone too far?

“Yeah – there’s that record, Korn III [Remember Who You Are, 2010]. I was pushing way too far, and it had the opposite effect, and I learned so much what not to do. Jonathan’s done interviews about, ‘I’ll never work with Ross again. I love him, but, you know…’ and I was like, ‘Oh, man, what did I do?’

“Basically, I know what I did, and I kind of did it on The Cure [their 2004 self-titled] record as well, where I wanted The Cure to be in the 70s or 1982’s Pornography, and Robert Smith’s in his mid-to-late 40s, and then there’s me pushing this sub-personality on him, like [makes loud roaring sound] not letting anything go by, and I feel like he’s saying, ‘Too loud’ on that record.

“I want you to be you today, and not try to repeat some fantasy of the past that I have in my frickin’ head, like, ‘This is what I crave, I know these guys better than they do.’ No, I don’t, I don’t know anything. But I do deeply, deeply know to absolutely respect the artist and what they are now. It’s funny, ’cos the album’s called Remember Who You Are, ha ha ha! And I had no fucking idea, Jesus, God.”

Eric Whitney, aka Ghostmane, told us that you made him cry because he was doing a song about his father…

“Ha ha ha! See, that’s the thing, I allowed him, and was there for that sweetheart to come through and not be held back. When somebody lets themselves be authentic all the way to the core, the body can’t handle it and it comes out as tears and love. Everybody says, ‘Ross made you cry’ – no, man, it’s not that at all, it’s not violent, it’s the absolute opposite. It’s violent to hold back. Let’s fucking go there, do it, just once, and it’ll last forever and ever and ever, it’ll keep playing at that same level of intensity. It won’t stop giving.”

How do you feel about being called ‘The Godfather Of Nu Metal’?

“I was extremely resistant to it when they started doing it during the Glassjaw days. I didn’t wanna be lumped in with all of the followers and the scene of silliness that happened afterwards, and I had a problem with that. Now, I think it’s sweet. If people wanna call me that, good.”

Eleanor was promoted to the role of Editor at Metal Hammer magazine after over seven years with the company, having previously served as Deputy Editor and Features Editor. Prior to joining Metal Hammer, El spent three years as Production Editor at Kerrang! and four years as Production Editor and Deputy Editor at Bizarre. She has also written for the likes of Classic Rock, Prog, Rock Sound and Visit London amongst others, and was a regular presenter on the Metal Hammer Podcast.