Rush’s sound had evolved and transformed over the course of the eight albums they made between their self-titled debut and Moving Pictures. But 1982’s Signals was a clean break with the past, pivoting away from the great guitar epics of the 70s towards a state-of-the-art keyboard-oriented sound – to the chagrin of some of their hardcore fans.

Not that Rush themselves were concerned. Rather than retreat to familiar ground, the trio instead opted to double down on their controversial new approach and fully embrace new sounds and technologies. Beginning with 1984’s Grace Under Pressure, their journey through the rest of the decade would take them far from their roots – something not every band member was comfortable with.

Signals was a pivotal album for Rush in many respects. As well as kicking off the third chapter of their career, it marked the point where they parted company with longtime producer and mentor Terry Brown. “We had to start right from the ground up in making things as different as we could,” said drummer Neil Peart of the decision.

To find a new producer for the follow-up to Signals, Rush began scouring the credits of albums they liked, drawing up a list of potential candidates. With studio time booked for November 1983 at Le Studio in Quebec, the band found themselves demoing new material and searching for a new producer simultaneously.

“Our method was to talk in general ways to each of the ‘candidates’ until we began to feel a bit more comfortable with each other, and then at some point play all of these songs – and expect them to offer intelligent criticism and suggestions,” said Peart of their recruitment modus operandi.

One person they considered was Steve Lillywhite, who had made his name working with Peter Gabriel and U2. Lillywhite signed up to produce, only to back shortly before work was due to begin. The band then tapped up Trevor Horn, who had helped Yes radically reinvent themselves on their 90125 album. That didn’t pan out either.

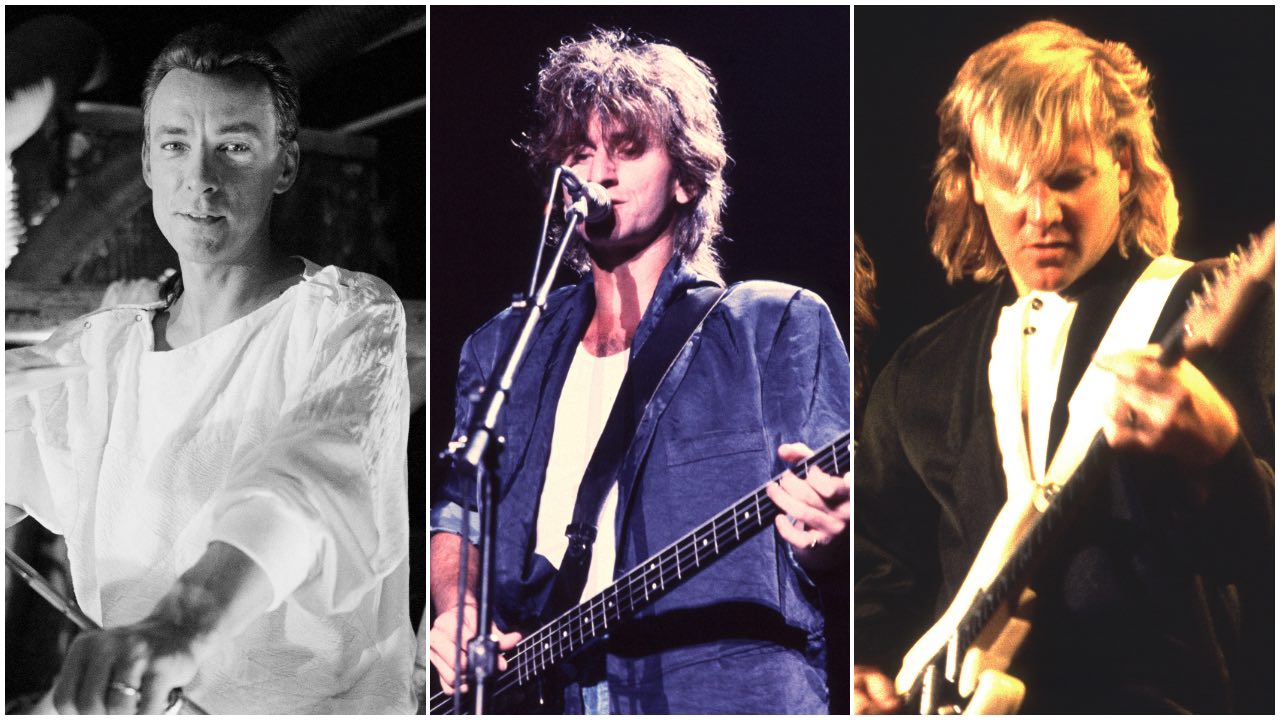

Eventually, someone did agree to produce the record: the British-born Peter Henderson, best known for his work with Supertramp. He found a band knee deep in new gadgets. Neil Peart had begun using Simmons drums – the hexagonal-shaped electronic kits made famous by Spandau Ballet and – while bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson spent more time than ever playing keyboards.

But Henderson proved to be a poor fit for Rush, and sessions stretched on for four months through a harsh Canadian winter into March 1984 – longer than on any previous album. The arduous process partly inspired the album’s title: Grace Under Pressure. “Not only was it relevant to so many of the songs, but it was also rather fitting to the way this album was going,” said Peart.

The finished product dialled back Signals’ synthesised sheen a little, making more space for Alex Lifeson’s guitar. Songs such as Red Sector A and Distant Early Warning became staples of the band’s set throughout the 80s, but Grace Under Pressure ultimately wasn’t the album Rush wanted it to be.

“It was a pretty low time,” Geddy Lee later said. “We weren’t sure of the kind of band we wanted to be. There was a lot of experimenting. We ended up pretty much producing that record on our own, and it was hard.”

The difficult nature of Grace Under Pressure’s creation prompted a change in approach for the follow-up, Power Windows. Henderson was not re-hired and the process of interviewing producers began again, albeit with new determination. “We want someone that has some sort of arrangement or musical input, someone who can give us a nudge and a push in directions that we haven’t gone in before,” said Lifeson at the time.

Having considered several options, they settled on another Englishman, Peter Collins, as co-producer. Other than one album by the heavy metal band Tygers Of Pan Tang, Collins’ CV showed focussed largely on pop acts such as Tracey Ullman and Nik Kershaw. But together with Australian engineer “Jimbo” Barton he proved a better fit for the band than his predecessor.

Pre-production on Power Windows began in February 1985, with a sojourn at a residential farmhouse studio in Ontario, utilising its 24-track desk to demo new songs. With eight tracks in hand, the band then decamped to the centuries-old setting of Oxfordshire’s Manor Studios to begin tracking.

In the Power Windows tourbook Peart noted: “The method of recording which Peter and Jimbo use allows us to record the basic tracks very quickly, and capture a lot of early, more spontaneous performances. We have the basic tracks finished in a couple of weeks, and are ready for a world of overdubs.”

Those overdubs would take place in Air Studios in Montserrat and at Sarm East, London. By moving around, the band were already making an album in a different way to its predecessor, opening themselves up to yet more innovation – such as recording a string section orchestra at Abbey Road and a 25-piece choir (for the end of Marathon) at Angel Studios. They engaged another Brit, Andy Richards – best known for his work with Frankie Goes To Hollywood – to help programme synthesisers and add keyboard textures alongside Lee.

Released in October 1985, Power Windows reached the UK and US Top 10s, though it is much more loved than its two immediate predecessors by fans and band alike. Lee now rates Power Windows as “the best from the keyboard period began with Signals”. Yet as Rush’s sound expanded, the role of Lifeson’s guitar was still often marginalised. “We were covering the tracks with sound,” said Lee, “and then Alex had to sort of fight his way in.”

Lifeson, ever the team player, wasn’t complaining: “Keyboards were the new thing, so there was this attitude: Let’s just push them up, they sound big and they sound cool.”

That ethos carried over into their next album, 1987’s Hold Your Fire, for which Rush re-hired Collins and engineer Barton and repeated the formula of using multiple residential studio settings. When Peart visited Lee in September 1986 to discuss the forthcoming sessions, he discovered that the bassist had been working on a new keyboard set-up entirely on an Apple Mac computer.

“It was an amazing thing,” said the drummer at the time, of what now seems like everyday technology. “After working out what he wanted to play in the conventional way, he could programme it all into the Mac and assign different parts to any number of separate keyboards. This proved very valuable to us.”

At the beginning of October, in the rural setting of Elora Sound, Ontario, Lifeson brought along a tape of experimental work he had been working on at home, while Lee had sorted recordings of the year’s batch of soundcheck jams into a sonic reference library of “potential verses, bridges, choruses and instrumental bits”.

With technology not only informing the creative process directly, it also had an indirect impact. The emerging CD format had many advantages over vinyl, not least its increased running time. Rush took advantage of that, recording 10 songs and 50 minutes of music rather than seven or eight songs over 40 or 45 minutes, as they had previously

For some, that increased length was too much of an average thing. Released in September 1987, Hold Your Fire is generally perceived as the weakest of the run of Rush’s post-Signals albums. The song Tai Shan, inspired by a visit Neil Peart paid to the ‘holy mountain’ Mount Tai in Shandong province during a bicycle trip to China, has been dismissed as the worst song Rush ever recorded by both Lee and Lifeson, with the latter claiming that hearing it made him want to “vomit”.

But it had a handful of stellar tracks too, not least first single Time Stand Still, which featured haunting guest vocals from singer Aimee Mann of Canadian alt-popsters ’Til Tuesday (the band had considered both Cyndi Lauper and Chrissie Hynde for the role).

Hold Your Fire was a relative commercial disappointment, becoming the first Rush album not to make the US Top 10 or the Top 5 in their native Canada since 1978’s Hemispheres. A now-customary live album, A Show Of Hands, marked the end of the latest four-album chapter of their career and their longstanding record deal with Mercury/Phonogram, after which the band took time off to take stock.

“We found ourselves free of deadlines and obligations – for the first time in fifteen years,” said Neil Peart. “We decided to make the most of that. We got to know ourselves and our families once again, and generally just backed away from the infectious machinery.”

When they did reconvene to make their next album, Presto, it would be with a renewed sense of purpose. Peter Collins had been replaced as producer by Rupert Hine, who had previously worked with The Fixx, Howard Jones and, most notably, Tina Turner (Hine had been on Rush’s list to produce Grace Under Pressure, but was tied up working on Turner’s Private Dancer). It quickly became evident that Hine was a fast worker.

“He came over with 10 days set aside for pre-production, figuring about a song a day,” recalled Alex Lifeson. “But after a day-and-a-half everything was done.”

Hine wasn’t afraid to speak his mind either. “The first thing I did was ask Geddy to lower his voice by an octave,” the producer later recalled. “It was just too shrill. He looked at me in shock. But he gave it a try, which impressed me.”

Hine’s presence in the producer’s chair wasn’t the only noticeable change. The synths and electronics that had dominated their sound earlier in the decade began to take a backseat. “I was getting sick of technology,” admitted Lee, “and wanted a return to a more basic approach.”

“When Geddy and I started writing this album, we started asking ourselves what was the real core of the band?” added Lifeson. “Where should all the emotion and the energy be coming from? We decided that it should really be the guitar. So we wrote with that in mind straight from the start, just bass and guitars like the old days. It was just more direct, we just added keyboards for colour.”

Released in November 1989, Presto was accompanied by a North American tour that found the band relying less on keyboards and sounding more like a power trio once more. Visually, too, they appeared to be stripping away the trappings of the 80s, ditching the mullets (Lee), hair gel (Lifeson) and shoulder-padded suits (both of them).

This journey back to basics was consolidated two years later with the follow-up album, 1991’s Roll The Bones, again produced by Rupert Hine.

“When we got back into the studio to start writing for Roll The Bones,” said Lee, “there was still a very optimistic atmosphere which had carried over from the Presto tour. I think we were much more of a band than we’d been in maybe seven to 10 years.”

Like Presto, Roll The Bones was ultimately completed ahead of time – two months, to be precise. But that still allowed one member of the band to scrutinise his own playing. “On the day we began setting up for the writing stage,” said Peart, “I stood in the little studio and watched Larry [Allen, longtime drum tech] putting my drums together. It occurred to me that I’d been using the same basic set-up for years, and maybe it was time for a rethink. Just putting the drums in different places might alter my approach to them, push me in some new directions.”

Conspicuously, he switched to a single bass drum with two pedals. For the others, too, everything just clicked into place. “We were really feeling very positive about the whole idea of the band,’ reflected Lifeson. “A lot of it had to do with Presto and how well we worked together. We realised that we really have a lot of fun playing in a band – which we’d maybe lost touch with. We sort of re-learned how to do it.”

Geddy Lee would later express reservations that the production on Roll The Bones could have “sounded bigger and bolder” but was proud of the material.

“There were some good songs on Presto – The Pass is absolutely one of the best things we’ve ever written, ” he said. “But the songwriting was so much stronger on Roll The Bones. I think what really makes the record is the quality of the songs.”

The commercial reception backed him up. Roll The Bones peaked at Number 3 in the US, giving Rush their highest chart position since Signals and restoring Rush to Platinum-selling status.

In subsequent years, the band looked back on their musical adventures during with mixed feelings. While Neil Peart and Geddy Lee viewed them as a necessary part of the band’s ongoing evolution, Alex Lifeson remained less happy with what the band had produced – particularly with regard to his own role within the musical framework.

“There were a couple of records that I’ll admit weren’t really that satisfying for me,” he said. “My heart wasn’t really in there. Those were interesting records that we made, and I like the songs on there and the sound and everything, but to me, I like to hear the guitar more upfront. I think the guitar is a very important instrument, not only because I play the guitar, I think it’s the instrument that carries all the passion, and if it’s gotta struggle to be heard, that just doesn’t seem right to me.”

Lee admitted that he hadn’t realised until much later how painful the period had been for his bandmate. “We’ve made a lot of mistakes on record,” he said, “but we’ve been able to learn from them and move forward. We’ve aged well because we’ve been able to apply the things we’ve learned. It’s all part of evolution.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Rush