It’s quiet out here. Or it was. Canadian country singer Ronnie Hawkins’ estate looks out on to Stoney Lake, a geographical idyll in Peterborough County in central Ontario. The surface of the lake is glassy and dark and so flat it looks like you could step out onto the water and walk to the furthest shore. The day’s a liquid blue, the clouds like pale abstractions or opaque afterthoughts dotted towards the horizon.

The dark wooden barn sits back on the property, away from the main house with its bay window looking out towards the serrated edges of fir trees that sit jaggedly against the sky. The barn rattles and hums all hours of the day and sometimes night. The frenetic writing sessions taking place inside fizz and fade as the orange burns out of the August afternoons. Although the keening guitars, rumbling bass and impossible drum parts aren’t the cause of consternation for the birds dotted among the woods this afternoon: it’s the strange, relentless engine hum overhead, a darting blur of propellor blades and a small engine that sounds like it might choke, stutter and disappear out of sight at any moment.

“Oh,” says Geddy Lee. “Alex [Lifeson] was in the heat of his ‘model aeroplane period’ at that point.” He makes inverted commas in the air with both fingers, faux-exasperated eyebrows arching upwards. “Even Broon [producer Terry Brown] had the stupidest aeroplane you’ve ever seen in your life.”

Lifeson: “I like to have a hobby when we’re working.”

Alex Lifeson is grinning like he’s still got that model aeroplane tucked under one arm and is heading to a vantage point to send it into the sky.

“I had a radio-controlled plane that I built there and crashed into the top of a truck. Might have been Broon’s truck? Bang, right into the top of the cab, put a hole in the roof,” he recalls. “But you should have seen the plane that Terry had. It was on these lines, and you flew it in circles, I guess. And the engine on it was probably 12,000 horsepower, and it went, like, 900 miles an hour. But in a circle.”

Lee: “It was going around and around, getting faster and faster and Terry was holding on to it and getting dizzier and dizzier…”

Lifeson: “And he had to let go of it. He was going around and around, and I was laughing so much that I had to lay down in the grass. There were literally tears in my eyes.”

Lee: “I was standing not too far from him. And when the thing took off, I had to hit the deck! This plane whizzing around overhead tethered to Broon – I mean, it had to come down eventually. He could barely stay upright. It was great. They were fun writing sessions, a good headspace.”

Lifeson: “As long as you weren’t being hit in the head, by, you know, Broon’s or

my plane…”

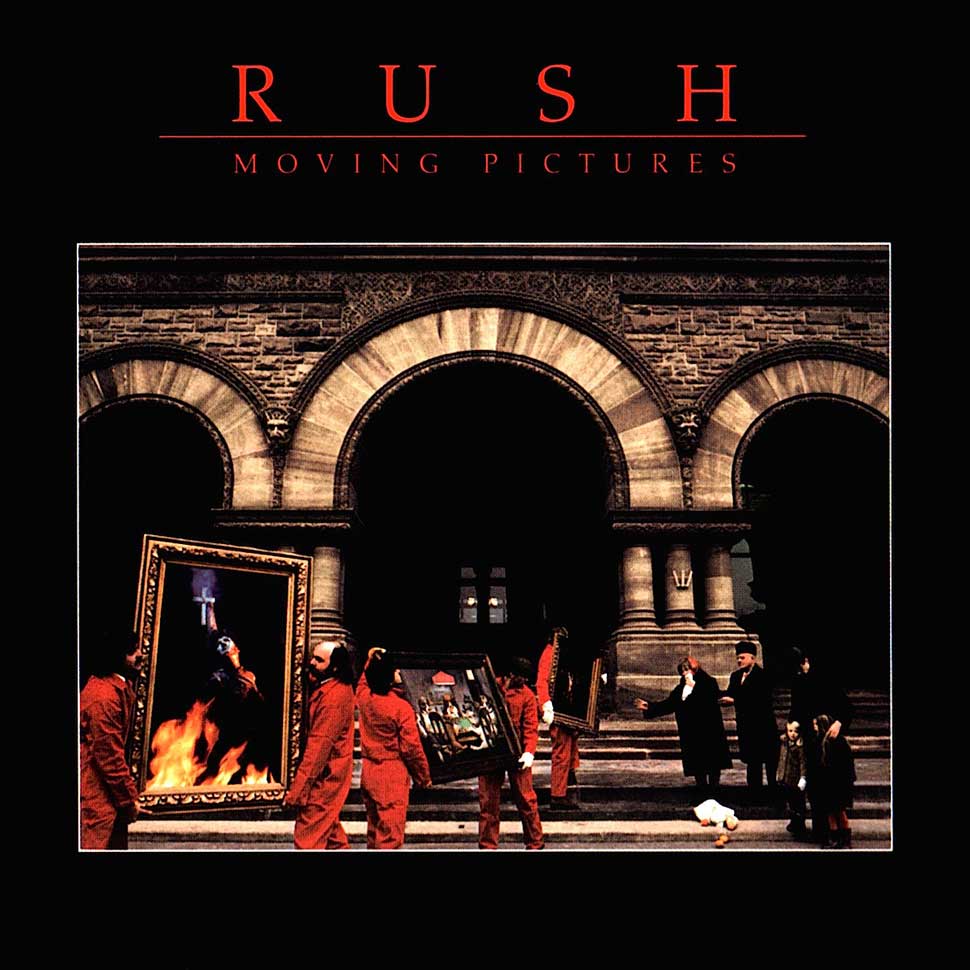

Welcome to the writing sessions for an album that would help define not only Rush, but also rock music in the early 80s: Moving Pictures.

It’s early 2022 and Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee are sat in their respective homes in Toronto, the town where they both met as gawky kids with ambitions of being in a band. Lee is in his living room, Lifeson in his home studio, the wall behind him hung with guitars. Even on a Zoom call, the sparky energy that kept them as friends and bandmates for over 40 years is still self-evident. They are, at turns, reflective, forgetful, deeply focused or simply goofy when it comes to recalling the summer writing stints – and autumn and winter recording sessions – that led to them making a record that would help propel them to platinum rock star status, and go on to dominate their live set until the band finally retired in 2015.

It’ll give readers some idea of the hectic writing, recording and touring schedule that the band were all undergoing at that point in their career that it was straight after they’d finished writing for Moving Pictures that they packed up their equipment, rescued Lifeson’s plane from a tree and set out to play some shows before heading to Morin-Heights to begin making Moving Pictures.

If you were lucky enough to see Rush play those dates in September 1980 – 16 scant shows – you’d have seen the trio showcase two brand-new songs too: Tom Sawyer and Limelight.

“We played them live on those shows?” asks Lifeson. “Did we?”

“To warm them up,” says Lee.

Lifeson: “Then how come Tom Sawyer was the hardest song to capture in the studio?”

Welcome to Le Studio. Now synonymous with the Rush name, they’d go on to record seven albums there, starting with Permanent Waves in 1980 and ending with 1993’s Counterparts. Set on Lake Perry and in the foothills of the spectacular Laurentian Mountains, you can see why a band might be drawn there, as Lee puts it: “It was truly a part of the great Canadian landscape.”

“A magical place,” remembers Lifeson, “but practical too; you could drive home within five hours. And the house and the view… We had a volleyball court outside – it was right on the lake. We had barbecues in the summer. Every time we went there, we went back to what we liked to think of as ‘our rooms’. It had that warm familiarity.”

In the summer: barbecues, or setting out onto the lake in a paddle boat or canoe. In the winter: snowshoeing, or taking to your skis.

“And before Le Studio,” says Lee, “you have to remember that we had been recording in Europe before we went there to make Permanent Waves, and all of a sudden, we’re in this really beautiful studio room and it has these giant picture windows and this insane view. The lake, the mountains and you’re banging away at Freewill, or whatever it might be. Le Studio was a revelation in the way we worked as a band; it was such a charming spot.”

And they even had their own French chef on site.

“That part of Quebec,” says Lee with a smile, “is French and English, so you know… it’s expected. And he was a very good chef.”

Tonight, though, Le Studio is cold and dark, a place filled with foreboding. The lake is icy and the air frigid. The studio lights pick out the figures massed on the drive leading up to the main building, silhouettes wrapped in scarves and hats, their breath rising above them in hazy clouds. News of John Lennon’s death that day has emanated from New York City. The band, who spent the autumn recording here, are back for overdubs and mixing, adding some elusive aural sparkle to the album. Sparkle that, for tonight at least, sees drummer Neil Peart rallying crew, studio staff and band members alike into what might pass for an angry mob as a precursor to the doomy intro for Witch Hunt (Part III Of Fear).

“We put microphones on the driveway,” says Lee, “and we got bundled up and went outside. We all started grunting and shouting stupid shit. We overdubbed over the top of ourselves over and over again until we created a vigilante mob. If you listen really carefully, you can hear some of the stupid things we said…”

“And the laughing, which was probably not what Neil was going for,” Lifeson adds. “We took a bottle of Scotch with us as well, which might explain the laughter.”

Lee: “A lot of laughter. It was good fun getting to do that.”

Lifeson: “‘Fucking football,’ which I think you can still hear if you listen closely enough – that was my line, one of the many recurring highlights.”

Though, as history bears out, that mob wasn’t meant to be there that night. The band should have been home. There was no plan for an album called Moving Pictures and no new studio album in the pipeline after the surprise crossover success of Permanent Waves. The idea was another live album, another tour; maybe to think about the next studio record. But such was the band’s momentum that they canned the idea of releasing a live album off the back of what had become their most successful tour and headed back into the Canadian countryside and to Le Studio.

“We were scheduled to do this big live album after Permanent Waves,” says Lifeson. “And at the last minute we said, ‘You know what? Fuck this, we’re not going to do a live album. We’re going to go back into the studio and do our next album.’ And that’s how Moving Pictures came to be. And it turned out to be the most important decision of our careers. Or the second most important decision, the first one being 2112, because without 2112, there would be no Rush.”

“It was actually a friend of ours who worked for Mercury at the time, Cliff Burnstein,” says Lee. “Cliff [who would go on to manage Metallica and Def Leppard as part of the Q Prime group] was responsible for getting us signed at Mercury. He was a huge fan of the first album. I remember we had played New York, and he came to the gig and we were talking about doing a live album. And he kind of said to us guys, ‘You know, Permanent Waves was so great that maybe you should think about going straight back in the studio to do another record.’

“So we talked about it and thought, ‘That does sound more fun!’ So that’s what we did, but Cliff sort of planted the seed of us changing.

“And it was exciting to suddenly change plans. ‘Okay, fuck it,’ you know? ‘We’re going back in the studio!’ And we were in a groove from Permanent Waves, we had kind of hit on a new style for ourselves; working in these shorter timeframes, but still building these complexities within those timeframes, and it was kind of an exciting period for us.”

“If you think about it,” says Lifeson, “Moving Pictures is the cute, sweet, happy offspring [of Permanent Waves]! We learned a lot about writing and how we work best to accomplish our goals so that an ambitious album such as Moving Pictures could be made without wanting to kill ourselves.”

As LP Hartley once wrote, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” With that in mind, more than 40 years is a lot of miles travelled. Little wonder, then, that the occasional question about that period in history draws perplexed glances or queries from Lee and Lifeson. Like Alex forgetting that they had aired two songs from Moving Pictures live before they even got near the studio, something Prog only learned about quite accidentally during a chat with producer Terry Brown. Ask the band now about the sublime, and possibly most Rush-sounding song on the album, the expansive-sounding The Camera Eye, with lyrics inspired by American writer John Dos Passos (who’s also said to have partly inspired Grand Designs and The Big Money), and the first thing Geddy can recall is the Christopher Reeve Superman movie.

“The thing I remember most about that song was playing around with the sound effects and overlaying movie soundtracks for the beginning and the ending,” he says. “It was fun shaping that kind of soundscape. Because it begins with a streetscape, we used a bit of dialogue from the Superman movie. We’d been watching it, I guess, and there’s a line that you can hear in the background that’s right out of that movie. So I remember creating those moments, but I don’t remember a hell of a lot about writing the song.”

“We were looking for moods,” adds Lifeson. “I do remember that much –moods that might suit the wide-eyed perspective of the first half and build to a climax for each section. But it wasn’t a conventional construction for a song by any means, and that’s us saying that.”

“I know how people perceive that album now,” says Lee. “And it is a landmark record, but when you’re writing a song, even those songs, you still vacillate between these moments of confidence and then moments of doubt. So, you waver between those two points until you hit something that you know works and excites you. But with The Camera Eye, because of the nature of the way the lyrics were on paper – it was more like prose – we approached it with the mindset of, ‘What’s the best way of explaining this?’ It needed a different approach to, say, something like Limelight, which was a much more obvious beast: verse, chorus, verse, chorus.

“And that all bleeds into our decision to stop the concept album thing – that was a big deal. We started to look at writing as a series of individual concepts, a series of smaller movies, in a way, which is what led to Moving Pictures and certainly to a song like The Camera Eye.”

For a lot of listeners, one of the highlights of Moving Pictures is the consistency of Neil Peart’s lyrics around that period. From Permanent Waves onwards we saw a distillation of Peart’s words; he was more concise, less broad strokes, and in a song like Limelight at his most revealing.

“I remember his writing in that period was very concise,” says Lee. “And although there always was a little bit of back and forth about one line or another, I don’t recall any major surgery or lyric changes around that time. As things progressed in our relationship, as singer to lyricist, that eventually changed, and I became more of a sounding board for him. Sometimes we would rearrange things, but I think for the most part in Moving Pictures, what he wrote was pretty much how we built the song. There was no major surgery going on. It was just our job to make a soundtrack for each one, to create these vignettes.”

Hold the moment. It’s a hazy afternoon up at Stoney Lake, a warm enough summer afternoon that the barn doors are open to let the daylight in. Neil’s off in some far corner of the estate, pen poised over his notebook, scratching away at some lyric ideas. Inside the barn there’s the familiar buzz of guitars and the low boom of Geddy’s bass riffing around a song, trying to find a way in.

“What was that?” asks Lee suddenly, looking up at Alex like a dog who’s just spotted a hare.

“Huh?” says Lifeson, who is already playing something else, willing his guitar to take him on to somewhere else.

Geddy, with the patience of a father who’s told his son to turn the music in his bedroom down one too many times, holds up a hand to pause proceedings and walks over to the tape machine spooling and whirring silently in the corner,

a constant in these frenetic writing sessions. The tape plays back and there, in the mash of arrangements and notes, is a diamond in the dirt: the opening riff to Limelight, intact, polished and bright. It was as if it had just fallen out of the sky and into their laps.

“It was pretty much like that, yeah,” admits Lifeson with the kind of shrug that suggests he stumbles upon $50 bills each time he leaves the house.

“So I go wind the tape again,” says Lee with a theatrical sigh. “And there’s the opening to Limelight. And that’s exactly why the tape was always on. Because before, if we used the tape and it wasn’t rolling, Al would play some amazing thing and I would say, ‘Holy shit, that was so great! Can you play it again?’ And he’d go, ‘Huh? No…’”

Lifeson: “I was already on to the next thing or the next version of whatever it was, that’s my problem. I just sort of impulsively play that way and it just keeps moving forward.”

He isn’t kidding. Prog once sat up very, very late on the balcony of a gilded hotel in Beverly Hills with Lifeson during the mix of the Clockwork Angels album, and as we made our way industriously through the mini bar and the sweet scent of smoke wreathed around us into the purple Californian night, Lifeson played his acoustic guitar mellifluously. Beautiful notes and arrangements went pealing away, intermingling with the wisps of West Coast dope someone had handed him earlier. There were three or four distinct moments when Prog stopped to ask what he was playing; not that he had any idea, he was just playing. We could have used a tape machine that night.

“Now I think about it, it’s just the same with my guitar solos,” says Lifeson. “The first five takes were always the best ones for the material. And then after that, I would just start repeating myself and I wouldn’t get the right vibe up, and then it would get to the point where I couldn’t objectively think of those pieces and put it together. And that’s when I get kicked out of the studio. Then these guys and the producer – whoever – would take the solos and they’d start snipping it all up and going through a bunch of permutations until they got the one solo they needed, and then I come back in. First of all, I’d go, ‘That’s amazing! I played that?’ And the second thing I’d say is, ‘Fuck me, I’m gonna have to play that live!’”

Correct us if we’re wrong, but it sounds like the bass player wrote Red Barchetta. The question makes Lifeson cackle and Lee shoot Prog a look like he’s just found us stuck to his shoe.

“I think you’ll find that Al and I both wrote that song,” he says. “I clearly remember writing the middle section: I remember writing that part on acoustic guitar. And then the whole ‘wind in my hair’ part, that whole section, but I think the main chordal pattern was Lerxst [Alex], and I just had room around that arpeggiated section where I could noodle. It gave me a lot of latitude. That’s why it sounds like the bass player wrote it.”

Lifeson: “I got to play the harmonics in a steady pattern that gave it a little bit of stability, while Ged and Neil were playing around with those accents, going off beat. We did that a lot over the years, where they would sort of go off and become the lead instruments and I would lay back and try to anchor it with an acoustic or with harmonics. Red Barchetta had that.”

Lee: “It was one of those songs where it might have been built on a more conventional sense of timekeeping, and we would listen back to it and think, ‘Well, that can be more interesting. Yeah, why don’t we start messing around with the time and that’s how it begins?’ And then Pratt [Neil] and I go off on this tangent and instead of landing on the beat, we can wait and land on the back of the beat. So, it was all in aid of being unpredictable.”

“Naturally, being Rush, we took it too far,” says Lifeson. “Years later, when we were constructing songs on the computer, if we were putting an arrangement together… well, then we could have all kinds of fun moving the beats around. But then we’d go to play it and everybody would be cursing it. Those are the parts that were the hardest to remember live and where most of the train wrecks came from. Like Earthshine, you know? Great song but so fucking hard to play live, because there was one chorus that was different so then it pushes the other two choruses. That could be a mess live.”

It’s late when Lifeson gets back to the barn one night, driving the five hours up from Toronto. Inside, Lee and Peart are beaming. They’ve written a new song they think might work for the album. Would Lerxst like to hear it?

“I stood there – hadn’t even been in the city that long,” remembers Lifeson. “And it’s the worst thing you can imagine: a fucking song written by the rhythm section! I have to fit a guitar part over this?”

His comic incredulity is fitting. Does he remember his reaction the first time he heard the jumble of riffs and pacing that was YYZ?

Lee: “Pratt and I had gone into the barn and we just started jamming to loosen up. I got this idea for that main riff, and so we just went back and forth. Then, before we knew it, we were putting a song together. Pratt would say, ‘Hey, it would be great if we had a part that was a bit more mellow now.’ And I’d say, ‘Well, I can use keyboards here.’ And then, almost out of nowhere, we had this song.”

“Then I had to learn that stupid bass part and transpose it to guitar. Thank you?” Lifeson says, laughing.

“One of the really cool things about that song, though, is that we were on a break and had gone home, and a friend of mine flew up to pick us up in a small plane. We were flying back to the city and, approaching the airport, they have this identifier, and it’s Morse code. It’s that ‘dada, dada, dada’ signal that would be the intro to the song. I don’t know – was it you, Ged, or was it Neil? But somebody said, ‘Hey, that’d be a cool way to start the song: with that rhythm, the identifier.’ And then, when we went back to the studio, we fit it in. And that’s such a signature.”

For a lot of people, the introduction to Rush’s biggest-selling record came with the deep, sonorous hum of the bass pedal that brought Tom Sawyer kicking into life. Prog has stood in Madison Square Garden as that self-same pedal opened the show and watched grown men wilt, bloom and throw beer over each other, simultaneously utterly in thrall to the booming opening chord and what it might bring. Tom Sawyer has become legion to Rush fans and never out of a live show since its inception on that first album tour. Naturally, this being Rush, it almost never made the album.

“I mean, when we were working on Tom Sawyer, actually for the longest time, it was the worst song on the record,” Lee reveals.

“We had more trouble with that song than almost any other song. I had real doubt about whether the song was working at all. I remember when we came to do the solo, and we’re having a lot of trouble getting a sound that you were happy with. All of a sudden, [album engineer] Paul Northfield kind of jumped into action and came up with this idea of miking the stereo speakers and doing your solo in a stereo spread. Then it gave it that kind of tubular sound. And then it finally came to life.

“But when we finished and were even mixing the song, and we’d had problems with the computer that was running the mix, so we all had our hands on different parts of the console operating it manually because we didn’t trust the fucking thing. We’d do a take and everybody was holding onto their section of the console. But even then, I remember having doubts about that song. Then when we heard it back in full, it was like, ‘Holy fuck!’ when those bass pedals came in. It was like, ‘Okay, this works.’ But up until that point, there was a lot of doubt about that song.”

And it was Tom Sawyer where he first laid down his infamous Rickenbacker bass and picked up the Fender Jazz. That was pretty much heresy to a lot of Rush fans.

“Yeah, I just couldn’t get the bass sound to work on that song. It was just weird, because I use the Rick on pretty much every other song on the record, but it wasn’t working on Tom Sawyer whatever we tried. There was a lot of fiddling and I think it created a negative association towards Tom Sawyer, but not when it was finished. It genuinely felt like a whole other song.”

Lifeson: “It went from being this immovable thing to the obvious candidate to open the record – that opening and then Neil’s drums. But I do remember it being a real relief to tick off the chalkboard.”

Lee: “We always had a chalkboard. We’d put the songs up and the parts left to record and would check them off as we worked.”

Lifeson: “Rupert Hine [producer on Presto and Roll The Bones] had a different kind of process where he used coloured Post-It notes for each of the jobs. The drums were maybe yellow, the vocals were maybe red. The guitar was maybe blue or green. And he would stick them all on the screen, on the window between the studio and control room. And as you finish the job, you took that one off until the window was clear. You could literally watch the progress of the album.”

Lee is quietly astounded. “I have a photo of that, and I could not remember what the notes were for! Yeah, like a musical advent calendar leading up to the finished album.”

Lifeson: “Did you tell him about MacGyver?”

Lee: “I didn’t. You tell him about MacGyver.”

For all their po-faced legacy, this is what it’s like to sit in a room with Lifeson and Lee as they toss dry bon mots back and forth with faces set like they’re playing a hand of poker.

“It was also used as the theme song for the Portuguese version of [TV spy show] MacGyver in Brazil.”

Lee: “That’s right.”

Tom Sawyer?

Lifeson: “Tom Sawyer, yeah. We went to Brazil and we couldn’t figure out how the fuck we got so popular there. And it turns out that they had overdubbed the original music for the TV show and had changed it to Tom Sawyer. And so everybody wanted to hear that song, because everybody knew it from fucking MacGyver!”

From the arduous journey that was Tom Sawyer – not only the album’s opener but one of the first songs to be written for the record – we now go to the last, the sprightly sounding Vital Signs. Conceived and created as if on a whim in Le Studio, its energy sparking off around the room, the giant picture windows picking out the lake below.

“It was the last song we wrote on the record, and we wrote it in the studio. It was a very spontaneous moment, a really nice thing,” says Lee. “After labouring the songs for a few months, just to go in as the three of us and see if we can just write a song, that’s a thing. We did the same thing again with New World Man, it was written like that. Certain albums have that one spontaneous song. And it’s funny because that song, those types of songs, end up being a precursor for some styles that we might do on the next record. Like a segue, almost. So, Vital Signs really kicked us off towards Signals without us even knowing it.”

It’s the summer of 1981, the first set of acclaimed Moving Pictures shows are done, and the band are back at Le Studio for yet another mix. But no hats and scarves or baying mobs this time: they’re here to work on the live mix of Exit… Stage Left, the album that was originally meant to follow Permanent Waves. The atmosphere is electric, the sun is high and so is the band’s mood.

Lee: “That was a really fun summer. We had the barbecues, we were out on the lake and because we had tonnes of time on our hands, because it was a live album mix, we didn’t have to be in the studio until we had to listen to it. And Le Studio being Le Studio, it was during those mixing sessions that we wrote Subdivisions. We were bored, we had a keyboard handy, and then we went back out in the autumn to promote Moving Pictures and Exit… That was a good time in our lives.”

It’s getting late; Lifeson has to go and meet family, Lee’s got another meeting he has to take. One more memory before we go from the final mixdown of the record and as the band were trying to push the album home. The weather’s picked up, it’s December 1980 and there’s a blizzard coming in over the mountains on the lake at Le Studio. There’s trouble inside the studio, too.

Lee: “We were having some weird issues with the electronics of the place because they had just gotten their new SSL board there. It was a bit buggy. It was one of the first SSL boards in the country and it was freaking out a little bit. I remember when we were mixing Tom Sawyer, Vital Signs and Limelight, we were having all kinds of crazy problems because there were these electronic spikes. They were actually changing the mix at the very last minute and we genuinely thought we were going bonkers, that we’d been in the studio too long, until they figured out what it was.”

Lifeson: “It was a grounding issue.”

Lee: “When we’d arrived it wasn’t super-cold. But by the time we left it was the dead of winter and there’s all kinds of moisture in the ground and a lot of snow. It shifted the atmosphere and so it was shorting out the desk. You’d see these spikes on the computer screen; you’d see each track had shifted when you hadn’t programmed them to move. You don’t want that when you’re mixing because you’re already crazy enough by that point!

“I remember leaving Le Studio that night and I had to get back to the city as I was meant to be heading off on holiday with my family, and by the time we left Morin-Heights this huge snowstorm had hit. I had Broon with me and I was in my old Porsche trying to negotiate these roads in this half-light with the snow just ricocheting off my windscreen. That’s sort of my enduring memory of the end of those sessions and that album: just trying to make it home.”

And now?

“I mean, it’s funny because those two records, Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures, are always connected for me. Yeah. Because one spurred the other in so many ways. They were both really a culmination of all the trial and error that had gone on a lot of the records before it. And after Exit… Stage Left, it was time for something else. It was a more turbulent process from then on in, because there were these other layers in our music, other textures, and the records became much more difficult to make over the next seven years.

“I guess what I’m trying to say is that after Moving Pictures, I don’t think we were ever the same band again.”

This article originally appeared in issue 129 of Prog Magazine.