“If you’re going to stay friends, you have to say something if someone’s out of line. We’ve kept egos in check all the way because of that.” How Rush’s Clockwork Angels became the prog icons’ perfect swansong

In 2012, Rush released their nineteenth and final studio album Clockwork Angels – and last words don’t come any better

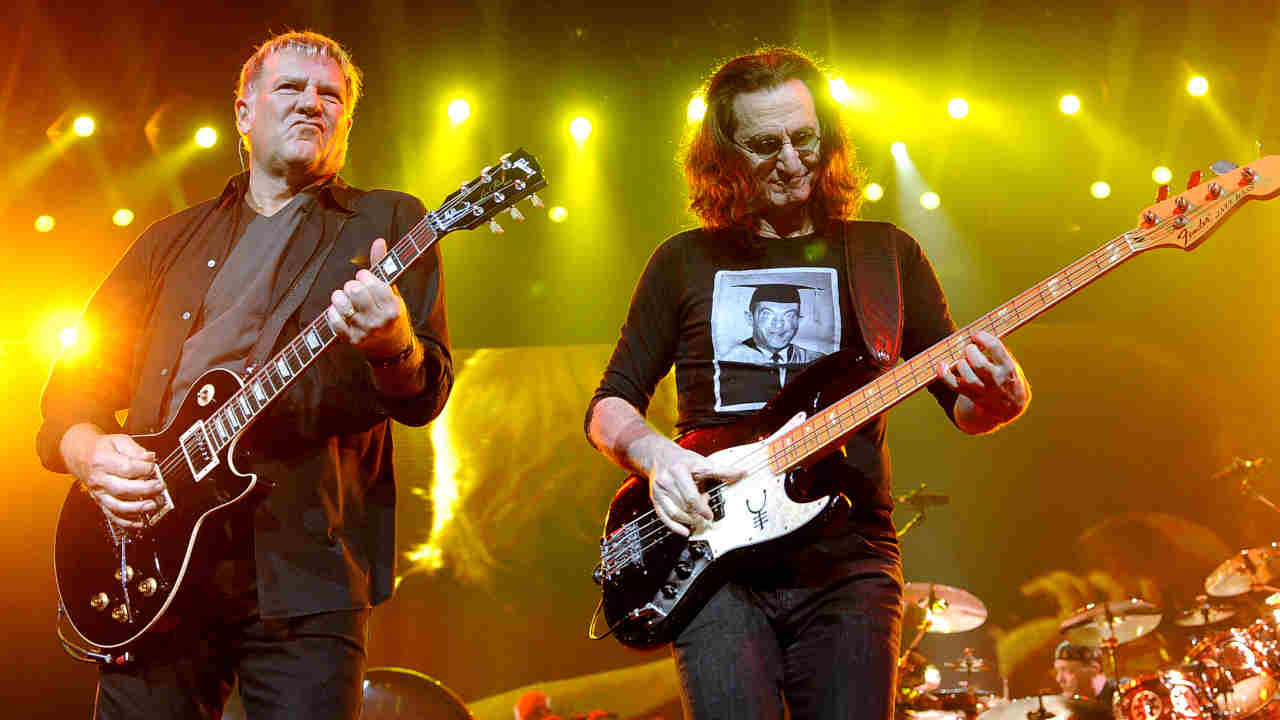

By 2012, the unthinkable had happened and Rush had finally become cool in the eyes of the rest of the world. The Canadian trio’s nineteenth album, Clockwork Angels, and the acclaimed documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage saw the band rightly showered with plaudits – something Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart seemed baffled by when Classic Rock caught up with them in Los Angeles.

The ultra-swish Beverley Hills restaurant is either an extreme exercise in discretion or Los Angeles has undergone some sort of power cut. The room’s so dark that the waiters carry small torches, like ushers in a cinema, just so patrons can read the menu more easily. In the half-light, Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee of Rush, various members of the band’s management and label, and the man from Classic Rock pull back chairs and peer across at each other in the gloom. Waiting staff hover close by, their hands lit up by small points of light, as if the restaurant’s home to a family of slow-moving fireflies.

Lifeson and Lee have moved into the hotel across the road while they’re finishing the mix of Rush’s new album, Clockwork Angels, at Henson Studios, a 20-minute drive to West Hollywood from here. As delighted as they are by the way their 20th studio album is turning out, after two months spent recording at Revolution Studio in Toronto, the initial mixing sessions in Los Angeles were brought to an abrupt halt by the death of the band’s long-standing photographer and friend, Andrew MacNaughtan, from a heart attack at the age of 47. The band had done a photo session with him the day before his death.

“I remember getting back to Toronto after that first mixing session – we just packed up and went home, you know?” says Geddy, as Lifeson nods in agreement. “Andrew had passed and I couldn’t sleep and so I got up and was nursing a Macallans, flicking through the channels and I saw that [Rush’s 2010 documentary] Beyond The Lighted Stage was on. I don’t know why, but I just started watching it.

“I started seeing things in it that I hadn’t noticed the first time,” continues Geddy, “listening to things a little differently, because when I saw it the first time I really didn’t want to – it was hard to watch. Watching yourself talk about your life, it’s not for me. But, my god, how strange to see your life up there on a television show in the middle of the night and I thought about all the different people that can’t sleep and are having the same experience I am, but they’re watching about my life. It’s just so bizarre.

“Billy Corgan, he blew my mind. The things he was saying about his relationship with his mother and what Entre Nous meant to him, and even Trent Reznor – those things meant a lot to me. You don’t start doing this for any other reasons but your own and, of course, 40 years later, you never expected that you’d still be doing it. And then to hear other people describe your work in such a serious light just makes you feel like you’ve lived a life and that’s such a nice feeling.”

“That,” says Alex with a grin, “and getting over the shock that a filmmaker made us interesting. We’ve had so many comments, like, ‘It’s a great film. I love the fact that they’re sweet guys who grew up together and had this dream and they’re funny and they’re family guys.’ It’s interesting the things that they latched onto and relate to in terms of their own relationships and struggles.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Geddy looks up from poring over the extensive wine list. “There’s been a huge shift in perception of us,” he says. “But just because we’re nice doesn’t mean you should like our music.”

There’s a pause as he glances around the room. “Though it does mean we get into restaurants a little easier now.”

Alex stabs his fork at the gargantuan starter – a crown of seafood that Heston Blumenthal might have built, dry ice billowing from its centre. The restaurant has comped the table.

“You spoke to Neil today, right?” asks Alex, eyebrows raised. “Did he stop for breath at any point?”

The Inn Of The Seventh Ray restaurant sits somewhere near the top of Topanga Canyon and is today alive with a thrumming new-age version of Greensleeves and the sound of a babbling brook. Topanaga’s been home to the musical great and the good for decades – an affluent, hillside bohemia that’s welcomed everyone from the Doors to Tool into its neighbourhoods.

It’s not hard to see the attraction on a sparkling spring afternoon. The tight corners leading up the canyon are worth it to get to the leafy plateau of a secluded main street. That the restaurant has its own bookshop filled with volumes on self-help and enlightenment comes as no surprise. That the soup on the menu is ‘created through the vibrations of each day’ seems perfectly plausible, especially after the first glass of Californian white and with the sunshine dappling through the trees.

“I thought,” says Neil Peart happily, “that we could do yoga instead of an interview.”

Just as CR is dreading the flourish of a yoga mat and an instruction to do the downward dog, Peart’s lays his sunglasses on the table, keen to begin talking.

It’s hard to underestimate the impact of Andrew MacNaughtan’s death on Rush, not least on Peart. It was his decision to first use the photographer, and it was Andrew who first introduced Neil to Carrie, his second wife. They were, in every sense, firm friends.

“We were very close to him, Carrie and I, to him and his partner, Alex,” says Peart. “It was devastating, but more disbelief really. Shocked. It’s still setting in. Anyone who’s lost someone will know that you keep seeing them. ‘Wait, there’s Andrew,’ you know? I remember he and I attended the South Park Halloween party. This was back in ’98. He was an SAS officer and I was Mandy, the English biker chick, a leather-clad, foam-enhanced drag queen. I stood seven-feet tall under a gigantic blonde bouffant. It’s weird, I just passed the store the other day. We went to get foam at this place at the bottom of La Brea. Andrew and I went there to buy the padding, then up to Hollywood to get the wig.”

Since 2007’s Snakes & Arrows, Rush have drifted, with a reassuring lack of guile on their part, towards the mainstream. An appearance on the The Colbert Report angered some diehard Rush fans when Stephen Colbert ‘accidentally’ walked on set as the band were in the middle of Tom Sawyer (Lee: “Some fans were really offended by that. They’ve made such a bond emotionally to the music that it’s hard for them to take lightly. It was funny, but to them it was sacrilege. Lighten up, would you? We’re just having some fun.”). Then there was a glowing revival piece in Rolling Stone, a series of sell-out tours, a cameo in Judd Apatow’s I Love You Man and the acclaimed and award-winning Beyond The Lighted Stage, which have all contributed to their ascension in the public’s eye.

Peart’s place at the heart of that film is pivotal to the journey it takes the viewer on. Whether it’s on screen talking about the double tragedy of losing his daughter and then his wife, or his elongated trek across the American continent as the ghost rider trying to outrun his pain.

“It was such a delicate subject matter,” says Sam Dunn now, one half of the production and direction team behind Lighted Stage. “We didn’t want them to think we were prying, but the fact of the matter is that what happened to Neil did affect the band. They thought it was over.”

Sam and his partner Scot McFadyen spent hours with the band and while both recognised the adversity Rush had struggled with, the pair were delighted to discover the band’s underlying sense of humour, not least about themselves.

“We had Geddy and Alex in the edit and we said, ‘Do you have any feedback?’” says McFadyen. “And they say, ‘Yeah, we like it… but could we have just a bit less of us?’ There’s the Rush humour in a nutshell. They make this serious, cerebral music, but there’s rarely a serious moment.”

Not least in the drunken dinner that the three attended at an old hunting lodge. It’s worth picking up the second disc of the DVD edition of Lighted Stage for the extended highlights of that meal alone. By the end of it, Peart has laughed for so hard and so long that the drummer’s the colour of an aubergine. “That was funny,” says McFadyen. “It was so hard to get the essence in the film credits because we were with them for three hours and they kept getting drunker and forgot the cameras were there. That’s how they are together: they’re goofballs with each other. And they love their red wine!”

Even the man who’s never watched that film is glad people got to see that dinner scene and, in a sense, the band’s inner self. “It’s good people saw that because it’s real,” says Peart. “That dinner was incredible. These three guys have been together all this time, but its warm and friendly as can be. Because we’re close, we balance each other, no one gets away with any of that shit, that’s the difference. When bands start to separate then each wedge can do whatever it wants and no one can say anything.

“If you’re going to stay friends then you’re going to say something if someone’s out of line in any way and we’ve kept egos in check all the way because of that. You can get an elevated opinion of yourself, but you can’t be friends and get away with doing that. If you’re going to be close then you have to stay level.

“Will I watch the film? I probably won’t, no. I’m not interested in it. I like reading my stories over, I listen to our music from time to time, but I never watch DVDs. I don’t look at myself – I’m not that kind of narcissist. And I know everything about it – my parents have seen it and everybody’s told me everything about it. I’ve lived it.”

It’s a day later and the band are at Henson Studios with irrepressibly upbeat producer Nick Raskulinecz who, admirably, is recording the Deftones in the morning and mixing Clockwork Angels in the afternoon. Out in the sunlit courtyard, Lee had stopped to show CR Charlie Chaplin’s footsteps embedded in the concrete. Chaplin first owned these Hollywood Studios and made both The Gold Rush and The Great Dictator here. Later, when it was A&M Studios, America’s answer to Feed The World, We Are The World, was recorded and filmed in the main studio here.

These days, since Jim Henson bought the place, a giant Kermit the Frog hangs out of one of the exterior walls and smaller, twin Kermits stand atop the gates as you enter the complex. Alice In Chains’s Jerry Cantrell (who sometimes plays golf with Lifeson) is working in a studio down the hall. In the back room, Lifeson and Peart are hovering about as the final song on the album, The Garden, is being mixed. As the song reveals itself, each band member ribs the other as original parts of the song they recorded have been dropped down in the mix or removed altogether.

“Oh, Neil, didn’t you come in earlier than that?” says Geddy happily.

In the small anteroom swathed with red and yellow drapes, the band are either sitting around or drifting in and out. Neil’s just recorded a voiceover for one of the shorter segues on the album while everyone stood around grinning. The mood – after a long mix and the worst possible interruption with Andrew’s death – is almost carefree. It feels like the last day of school. Earlier, when CR was interviewing Lifeson, Neil had appeared at the glass wall dividing the studios with a handwritten sign that said: “Stop Talking Now!” When CR brings it up later, he gives a look of mock-seriousness: “I was obviously talking to Alex,” he says.

“Nobody takes the piss out of themselves to the extremes that we do,” says Geddy. It’s early evening and conversation has turned to the film shorts that are regular highlights of the band’s live show. Lifeson, who has something of a minor acting sideline going on – watch out for him soon as Dr Figg opposite Billy Boyd in the adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s Ecstasy – is, everyone agrees, very keen to get in front of the camera.

“I don’t care what else he acts in,” says Geddy, “he always acts best in our films. I always think of the most ridiculous get-ups for him. ‘Al, how about you be a real fat guy?’ He really takes to it. Those three characters that appeared in the films from the Time Machine tour are the three essential character aspects of us.

“When we designed those characters, I wanted them to represent the inner us: inside Big Al is this big, fat, crazy inventor, who loves to eat – that’s Al. And Neil’s got the furrowed-brow Irishman with the Waspy background and I’m this crazy sausage maker! The wigs are very good too.

“I think it’s fun, and sometimes it’s funny to watch the audience, especially somewhere like Helsinki – some things don’t cross the language barrier. You look out and it’s this sea of perplexed faces, an audience of bewilderment. We’re going to continue to make them. I hope people like them! The first time I saw Jethro Tull was on the Thick As A Brick tour and they were so good playing-wise, but their production was so much fun – they had a sense of humour that kept occurring and it really stayed with me as what a lovely bonus to give an audience that’s sitting there for three hours listening to this intense music – and our music is a little on the bombastic side, so I think it’s nice to give some candy. It’s nice to see them smiling.”

“It’s always been that way – Geddy handles the visual stuff, I’m our de facto graphic art editor,” says Neil, who is, incidentally, studying the album artwork on his laptop. “And Alex, he’s the musical scientist. We all have our roles in there. Plus, Alex looks dazzling when he’s all dressed up.”

Nick Raskulinecz first worked with Rush on Snakes & Arrows. As a long-term fan, he pushed for the co-producer’s role. He remembers them then as a band who were trying to redefine themselves and find where they fitted in.

“I feel like they kind of lost their path a little bit,” he says. “They didn’t really know where to go and what to do and what to sound like because music had changed dramatically from Test For Echo to Vapor Trails, and then from that to Snakes & Arrows, music had changed again. There are five-year gaps between all those albums and things were really different, so it was, do we try and sound like music now or do we try and sound like us? Are we making songs for the radio? How do we make Rush be Rush in three and a half minutes? That’s the standard – how do we keep people’s attention? Do we go for new fans or do we please our old fans?”

As history bears out, Raskulinecz managed to help the band embrace the new, but not be afraid to give a nod to their past – the ringing guitar chord from Hemispheres reappeared as a motif in Far Cry and, even more remarkably, bass pedals were back in the mix.

“To be fair,” says Raskulinecz, “they didn’t resist any of it. The hardest part about the bass pedals was finding a set because they didn’t have them any more. We called a company in Toronto and rented these bass pedals and had them shipped to the studio. Geddy’s sitting there, we take the lid off and he’s like, ‘Whoa, these are the ones we used on the Permanent Waves tour and then sold!’ I was like, ‘You got rid of these? Are you kidding me?’”

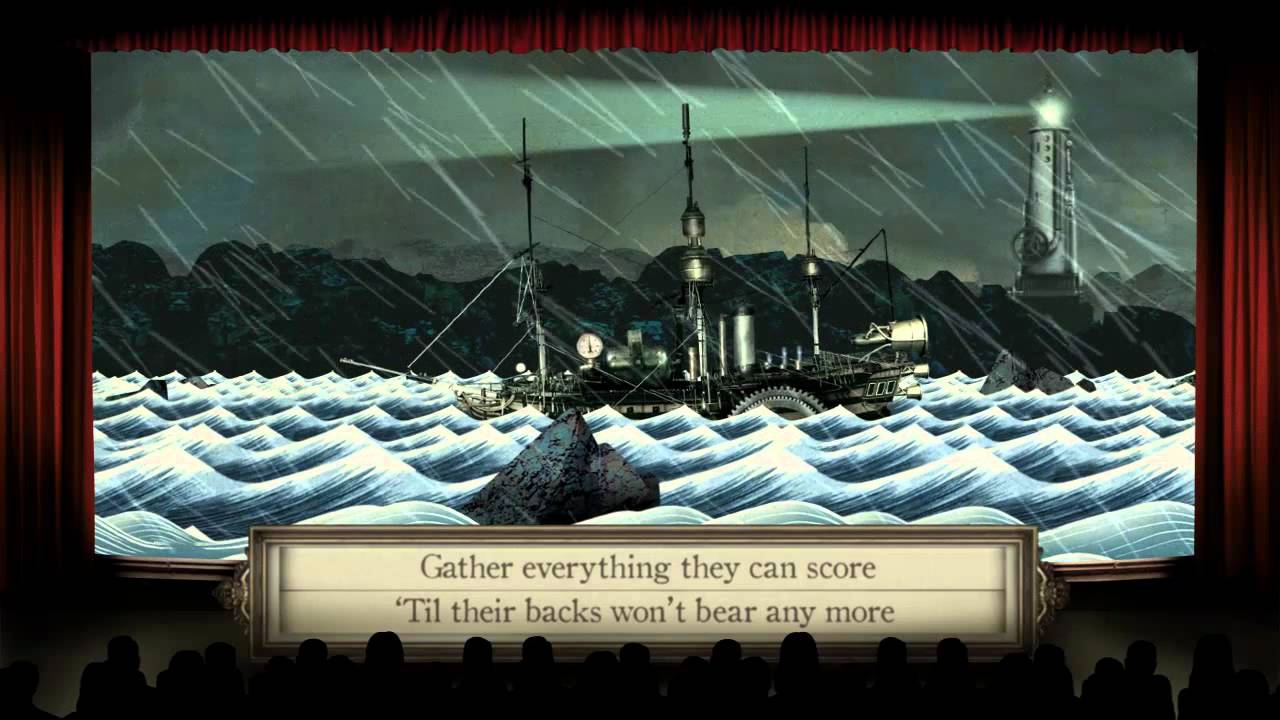

Which brings us another five years later to Clockwork Angels. A complete concept album – the band’s first – centred, in part, around a young man’s quest set against a world of steampunk, clockwork and alchemy (Lee: “A concept album – I know, that’s what we’ve been joking about all this time! We kept saying, ‘It’s Caress of Steel all over again. Get ready for the Down The Tubes tour part two!’”). Peart’s borrowed from sources as diverse as Daphne Du Maurier, Joseph Conrad and Voltaire’s Candide to move the story along.

Long-term fans of the band will find much to love: the thundering Headlong Flight recalls, in part, Bastille Day, while the expansive, multi-layered and intricate title track is as good as anything the band has ever recorded.

Peart says he hopes that song will be in their live show forever. “What was it that Oscar Wilde said: self-plagiarism is style?” says Peart. “We certainly do a few tongue-in-cheek nods to Bastille Day in Headlong Flight – that’s deliberate.

“I got to reference my teacher and friend Freddie Gruber, who died last year, in there too. He gave me that line from the song, ‘I wish I could do it all again’, because there he is, 84, he grew up in New York in the 40s, worked out through Chicago and Vegas in the 50s, LA in the 60s and since then his path has crossed with everybody. His response to it all was, ‘I’ve had quite a ride – I wish I could do it all again.’ So I got to make it personal, but universal too, you know?

“The starting point with the concept was the steampunk idea. I love how it’s a direct counterpoint to cyberpunk – it’s like a different vision of the future. So I was enthralled by that theme and my character’s journey through this world. I also had in mind Voltaire’s Candide too, that was a germ of it. Plus there was so much stuff I’d been reading about the circus stuff, which became Carnies, from Robertson Davies’ novels. And I’d read a lot of history from the south-western part of the US and that figured into the story of the explorer Coronado, who kept going out into the desert to find the fabled cities of gold. And The Wreckers was actually from Daphne Du Maurier – that’s been in my mind for 30 years. I guess it’s an episode in Jamaica Inn. So all of that coalesced into the character and the history of the story, the whole concept.”

Almost 40 years into their career, Rush are changing the way they get things done. The Time Machine tour saw them improvising, for the first time, live on stage. Each night, Working Man became an exercise in pushing things as far as they could go. That transferred to this latest album. For the first time ever, Peart didn’t prepare his drum parts but just came in and played them live: 75 per cent of his playing on Clockwork Angels is improvised and was done in one take.

Lifeson says as he’s 58 now, he couldn’t give a shit about how people perceive him or the way the band works. His attitude, happily, appears to be spreading to the rest of his bandmates. “Certainly, a lot of it is confidence too – we feel very confident in our playing and where we are and where we’re going,” he says. “I’ve got nothing to prove – I’m just going to do what I’m going to do and let it go. And that’s what happened. Ged and I were getting these drum tracks back from Neil and were like, ‘My god, that’s amazing – he never plays like this!’ There are so many parts and so many cool things and consequently, that gets you all fired up and you try a bunch of different things.

“Hence Ged and I swapping instruments on The Wreckers. We were on a break and Ged picked up one of my guitars and he started messing around, and I remember he got up and came back with some lyrics. Then he sat in the corner playing the melody for the verses and I thought, ‘Wow, this sounds great.’ He just wanted to put it down very quickly and I grabbed his bass and we ended up recording the demo with him playing guitar and me playing bass – it was great! He played on the record, but it’s my bass part, which is really cool. When we swap instruments, we sound like Barenaked Ladies, which was a surprise. We had to Rush-ify the song.”

Lee says they’ve never played better live than on this last tour. Also, because of the live jams on the Time Machine tour, they’ve gone back to writing and working as a band the way they did when they were starting to make their mark on the world.

“I don’t know why we took so long to get back to that place,” says Lee. “You have ways of writing and sometimes you ignore the obvious. And the obvious always comes back to what you are as a band and we’re players first, always. But somewhere along the way we missed that connection on how that playing informs the writing.

“We forgot that’s how we used to write in the old days – that’s how we wrote Spirit Of Radio, that’s how Tom Sawyer was written, all of us together in a room jamming. So without realising it, our playing was informing our writing right from the get go and then we went away from that. We separated that from what I guess is essentially Rush.”

After this record they’ll be without a deal, which doesn’t bother the band at all. They admit the live shows might be stripped back at some point as the long tours are finally taking their toll, but, in Alex’s words, they’re going to make records until they die. At one point during the mix in LA, they posit that the next few years would see the band finally playing some festival shows too.

“We were such control freaks for so many years,” says Lee, “we didn’t want to go anywhere where we couldn’t control the environment, so we’re learning that wherever we play, that’s our show. And at the end of the day, it’s about the playing and the songs and it’ll be fine.”

It’s a very long way from the band’s management offices in Toronto in the spring of 2002. Vapor Trails was just about to be released after the band’s protracted and enforced sabbatical after the death of Peart’s daughter and then his wife. At the time, Lee had told CR that: “I don’t think about making more Rush albums really. I want to enjoy my life as much as possible. I know I can’t really get on without writing, but I don’t know whether it necessarily has to be with Rush any more.

“We did an album and it worked out. Hopefully the tour will be something we won’t regret three months from now. I get tired of waking up with no throat and this is the most ambitious tour we’ve embarked on in 15 years and I hope that’s not a mistake. Maybe it’ll be the last big tour we do. Don’t get me wrong, Vapor Trails is, in some ways, the most successful journey that the three of us have been on together so it’s very possible that we’ll repeat that experience, but I don’t want to take anything for granted any more. After all that’s happened, how can we?”

Time, as the saying goes, is a great healer. Ten years later, the three members of Rush are re-energised, goofy, having the time of their lives. They still complain about the long tours and talk about cutting the shows back, but never do (Lifeson: “We’ve been saying that for 20 years – still hasn’t happened”), and these are the kind of stories Geddy Lee gets to tell now:

“When we were living at the London Hotel here, while we’re mixing the first time around before Andrew passed, right around two or three in the morning I’d be just drifting off to sleep and I’d hear this acoustic guitar playing and I’d be, ‘I know that sound.’ And Big Al would be out on his balcony, which was right underneath mine – he’d had some refreshment, apparently – and he’d be just playing to LA. He plays all the time.

“And I would just lie there in the darkness and look up at the ceiling with this huge smile on my face every night even if he had just woken me up. I knew the headspace he was in and I knew what he was doing – he was being Al and he was playing to LA. Those moments are forever – so sweet, so funny.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 172, May 2012