There are several distinct phases in the epic career of Rush. While today they are pigeonholed as progressive rockers, they didn’t start out that way. The Canadian combo hail from a time when a group’s importance was in its album-selling potential. Bands were given quite a few chances by the corporate number crunchers before judgements were passed regarding their future. These were the days when artists were allowed to marinate in their own creative juices. No one demanded instant microwaved solutions.

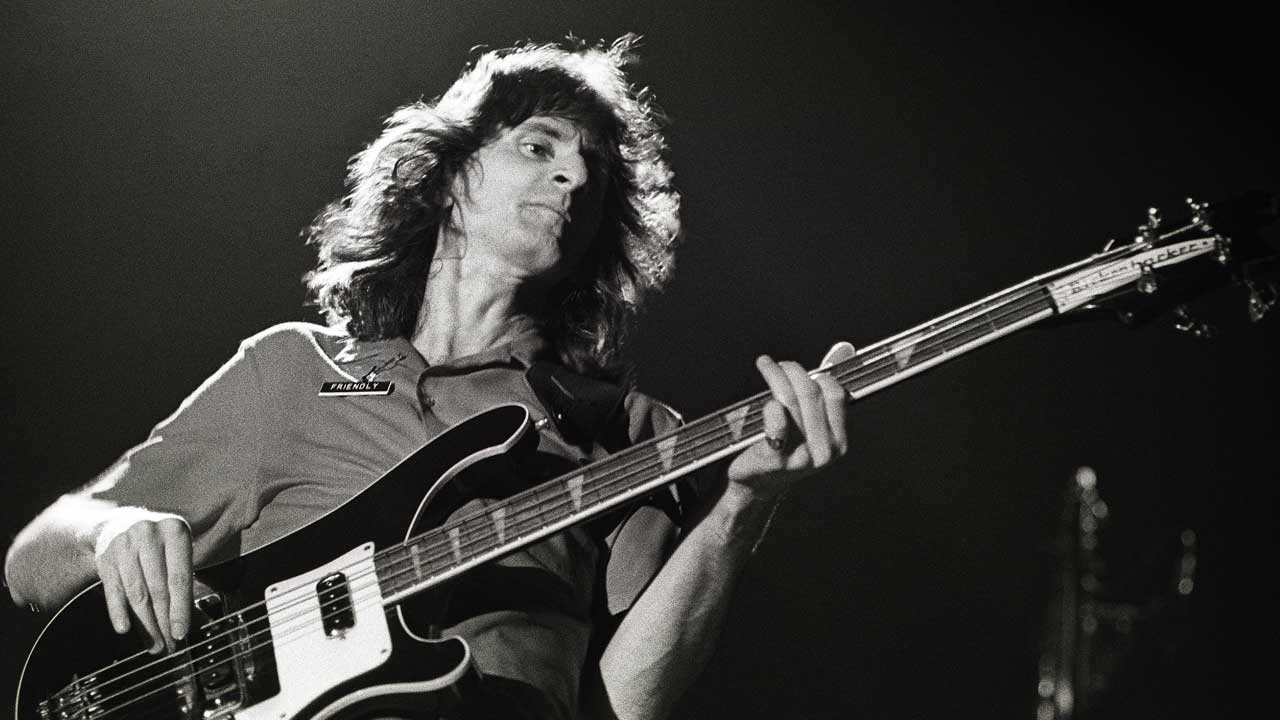

Rush debuted way back in 1973 when they released a mildly ridiculous cover of Buddy Holly’s Not Fade Away as a single. But they learned their craft quickly. When their first album came out two years later, they had metamorphosed into Led Zeppelin-alikes, characterised by bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee’s mutilated Robert-Plant-on-helium squeals.

It didn’t stop there. A change of drummer (the bombastic Neil Peart replacing the workmanlike John Rutsey) inspired Rush to embrace sword, sorcery and all things mystical. They conjured up grandiose Tolkienesque visions while Peter Jackson was still struggling to focus his Box Brownie. (Can you imagine how the Lord Of The Rings director might’ve envisioned Rush’s fantastical tussle between By-Tor and the Snow Dog? Sheesh!)

To many, Rush albums such as Fly By Night, Caress Of Steel, 2112, All The World’s A Stage and A Farewell To Kings – all released during a phenomenally creative period between 1975 and 1977 – filled the huge cavity left by the musical decline of bands such as Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Yet there was a difference. Rush had the shrieking vocals and pounding bass of Lee, the gritty guitar of Alex Lifeson, and the flashy drum work of Peart. They were an archetypal power trio. They were, in fact, the first band to make prog rock.

Rush’s most radical, and enduring, phase came two years after the transitional Hemispheres (1978) when they made a determined effort to streamline their music and become – in the best tradition of modern-day prog – super-musicianly and hyperproficient. Eschewing satin cloaks for Don Johnson-style power-suits, and even experimenting with reggae beats on occasion, Rush’s Permanent Waves album marked the start of the band we know today.

“That was probably our first record that was in touch with reality,” Peart once recalled. “It was about people dealing with technology instead of people dealing with some futuristic fantasy world.”

“We’ve experimented with all those weird time signatures and made all those big points that we wanted to make,” added Lee. “Now, with Permanent Waves, it’s time to move on.”

The loon-panted warriors had become icy-cool technocrats. Purveyors of über-prog, if you will. It was a direction that confused people initially. Rush maintained links with their past by still playing their old songs live, although they were often in medley form and with lyrics altered playfully. For example, eagle-eared aficionados noticed a line in the sci-fi epic 2112 – ‘We are the priests of the Temples Of Syrinx’ – would often be amended to ‘We are the plumbers who’ve come to fix your sink’.

This writer interviewed Geddy Lee in November 1981 – the year when Rush released the follow-up to Permanent Waves, Moving Pictures, which spawned the hit single Tom Sawyer. A long-standing fan at the time, I was still struggling to get to grips with the Toronto triumvirate’s ‘new’ direction. But there was no looking back. The smouldering joss sticks had been doused. The Michael Moorcock novels had been consigned to the remainder bin. Rush were more Red Barchetta than Rivendell; more Freewill than Finding My Way. Edited interview highlights follow…

Will Rush ever record a 20-minute track like 2112 again?

Lee: It came to a point where we had to make a major decision. We had to ask ourselves what we wanted to do. Did we want to become known as a progressive rock band that just does epics? Doing a 20-minute tune is very good for us as musicians; it’s a real challenge. And as a songwriter you really have to pace your material – it’s a lot of work and it’s really good to get your technical things and your craft together.

But conceptually, we thought, it was all getting a bit stale. That’s why we decided to assimilate all these many, many experiments that we call albums and see what we could come up with just as good songwriters. And that’s when I think we found a happier place to be.

Moving Pictures is a prime example of this more concise way of prog thinking. Tracks like Tom Sawyer and Red Barchetta are sparse and modern-sounding, and clock in around the ‘mere’ four- to six-minute mark.

Feel is becoming so much more important in our music. Moving Pictures is the first album we’ve recorded where we can sit back and listen to and say: “Hey, this doesn’t sound forced in any way.” It’s just real natural. Before, we used to worry about staying on one groove too long. We used to chop and change things and add lots of special effects. And before we knew where we were, we had this monster progressive rock song on our hands. Now I think we’re beginning to appreciate staying in a groove, and then maybe just shading that groove a little bit… that’s where we’ve been concentrating our energies. And I like it myself, I think doing what we’re doing makes for much better rock songs.

Are you becoming progressive in your outlook as well as in your music?

With regard to the sword and sorcery approach, we could not stay in that moment. We decided that we wanted to stay together as a band, because we enjoy working with each other. We reckon there are lots of things we can handle in the progressive rock scope, eventually. So every once in a while we take a turn off on to a side road or something. Just to keep things interesting, you know.

There was a flamboyant nature to Rush in the past. Now you seem content to let the music do the talking.

A lot of prog bands appear to revel in their anonymity. There’s a track on Moving Pictures called Limelight. Playing in a band, you have all these millions of things expected of you. And you sit there and you try to remember why you’re wading through all these interviews, and why all these people are demanding part of your time. Finally, you go: “No, it’s all bullshit.” The reason I got into a band was to play, and play for people. And the trouble is, most of the time you’re in the limelight it becomes very difficult to keep a hold of and recognise this fact. So many people get hung up on the other aspects of being in a band, of being in the limelight – which, from our point of view, is the garbage side of the music business. And because of the kind of band we are, I’m sure that if we did get involved in that other side too much, it’d be detrimental to our music and affect our psyche, our well-being.

Experimentalism is key to any progressive rock band’s approach, and reggae is just one new influence that’s creeping into Rush’s music. How did it come about?

That’s just the beginning of – as I was saying earlier – paying more attention to feel. Listening to reggae and some of the funkier new music that’s been coming out recently, I think at last we’re beginning to appreciate what the word ‘feel’ really means. I’m sure there’ll be other styles coming to light in our music in the future.

Are you a fan of the so-called New Romantics? [This big-shouldered and floppy-haired musical movement was a big deal back in 1981.]

Spandau Ballet, Visage, Ultravox… there’s some good music going down. The thing I really like is that the bands concerned are being highly creative. They’re applying feel to technology with synthesis and it all sounds really positive, really progressive. It’s a happy music too, the whole antithesis of the punk movement which got too angry and hateful for me.

You’ve probably blown the boundaries of progressive rock wide open with those comments.

There’s nothing wrong with recognising good music, even if it’s not to your taste at the time. As a musician it’s my obligation to remain in tune with trends, and to be in touch with what’s going on. If I want to remain a contemporary musician – a debatable point to some people, I suppose – it’s something I’ve just got to do. You’d have to be considered a fool to ignore good music, no matter where it’s coming from. And no matter how progressive it is.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 97, published in September 2006.