It was the biggest album of their career, a multi-million selling masterpiece that elevated Rush from cult heroes to one of the world’s premier rock acts. As guitarist Alex Lifeson said of Moving Pictures when speaking to Classic Rock in 2012: “That record changed our lives.” And yet, for this band, nothing was ever simple.

“It’s always hard to make records,” Lifeson said. “It’s an enormous drain emotionally.”

In the making of their eighth album, Rush had to dig deep – so much so that immediately after the recording was completed, bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee harboured serious doubts about what they had created.

“It took us so long to make the record,” he said. “By the time we left the studio it was the dead of winter. I had to drive home through this horrible snowstorm. Then, without any sleep, I took a flight to the Caribbean for a holiday with my wife. And when I listened to the record out there, I was so burnt out that it sounded all wrong.”

But it was Neil Peart who felt most conflicted. For the drummer and lyricist, fame was not a blessing but a curse. “I didn’t want to be famous,” he once said. “I wanted to be good! It’s a whole other thing.” And in one song from Moving Pictures, he made his feelings explicit. Lifeson described Limelight as “a straightforward rock song”, but in the words written by Peart were complex emotions and a blunt message to fans: “I can’t pretend a stranger is a long awaited friend”.

At the very point the band was making music that would connect with a vast audience, Neil Peart was already counting the cost of that success.

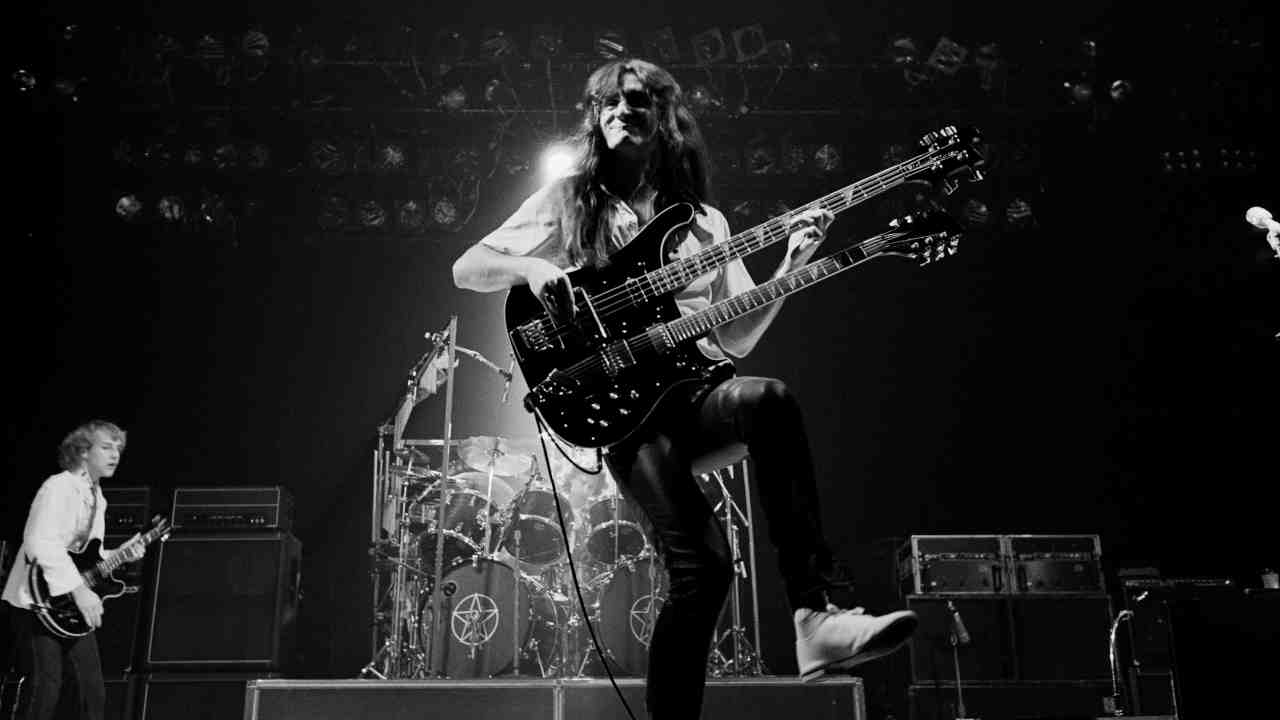

In the summer of 1980, when the three members of Rush began writing for Moving Pictures at a rural retreat in Stony Lake, Ontario, their confidence was high. Their most recent album, Permanent Waves, released in January of that year, had been a significant breakthrough, both artistically and commercially. With the onus shifted, as Lifeson explained it, to “shorter, punchier songs”, Permanent Waves was the big leap forward with which Rush defined a new sound for the new decade – a sound most perfectly illustrated in The Spirit Of Radio, the complex yet tightly focused and euphoric anthem in which the band’s virtuoso musicianship was distilled into five minutes, resulting in their first hit single. With this transition complete, the stage was set for Moving Pictures.

“We were originally going to do a live album,” Lee said. “But then a friend of ours suggested that, as we were changing our style so fast, we should really think about delaying the live album and go into the studio again. We thought about it, and this made sense.”

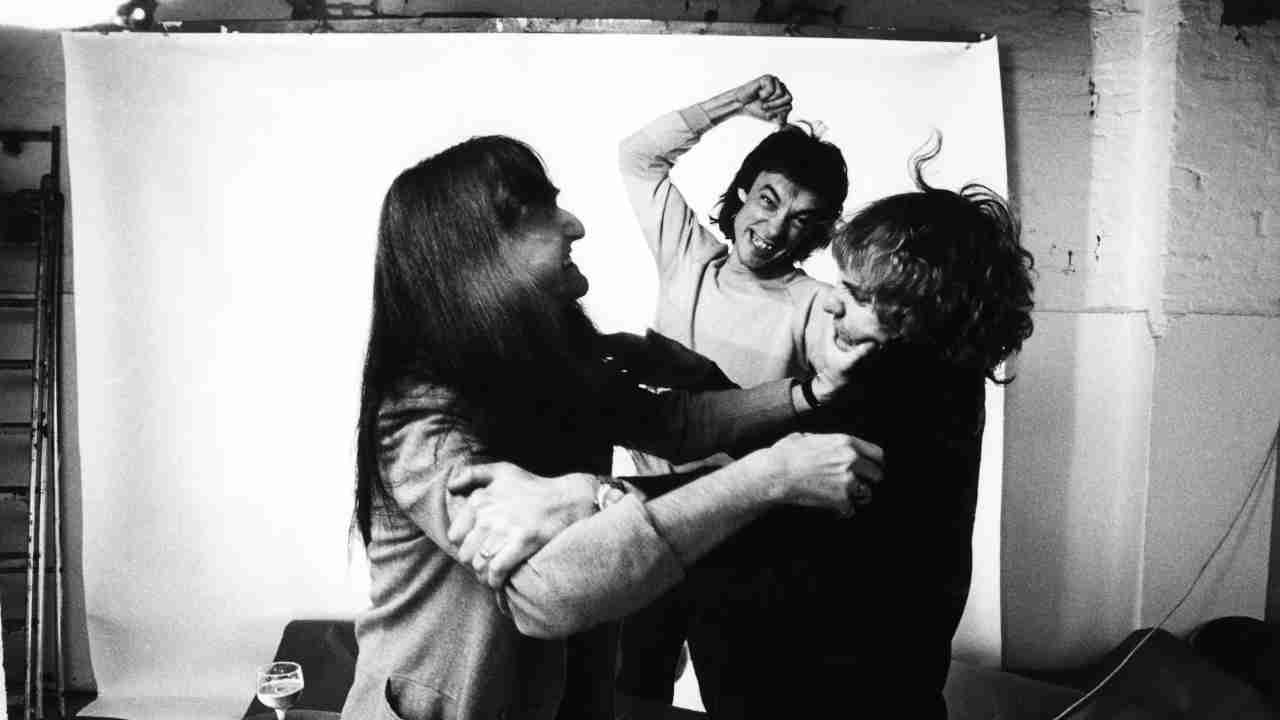

On July 28, shortly before they left for Stony Lake, Rush had joined up with fellow Canadian band Max Webster to record the song Battle Scar. An epic jam, cut live, with both bands going at it full tilt, Battle Scar would be the centrepiece of Max Webster’s album Universal Juveniles. It was while the two bands were together that day, at Phase One Studios, that Pye Dubois, a poet and lyricist who worked with Max Webster, presented a new song to his friends in Rush – “humbly suggesting,” as Peart recalled, “that it might be suitable for us.”

Dubois wasn’t wrong. The idea he had, in embryonic form, would be developed into a statement piece for Rush. It would become the opening track on Moving Pictures, and, ultimately, the most famous of all Rush songs – Tom Sawyer.

On arrival in Stony Lake, the rough outline of Tom Sawyer was all they had to work with. “We had nothing at all written for the album at the time,” Lee said. “It was a case of starting it all from scratch.” Their gear was set up in the barn adjacent to the house they had rented, and there they worked standard business hours. “Monday to Friday,” Lee said. “And then we went home for the weekend. That’s how we tended to do things in those days.”

In this relaxed environment, new songs came together quickly. As Lifeson explained: “Most of that record was written by all of us at the same time, in the room jamming with an idea and everybody going from there.”

By Lee’s recollection, the first song completed was The Camera Eye. At more than ten minutes in length, this was something of an anomaly in the context of where the band was headed, more of a throwback to the band’s 70s work, as Lee would later admit. “The Camera Eye was the last really epic song we wrote,” he said. “And at the time I thought it was too long, and it sounded derivative – kind of a Genesis wannabe. It didn’t feel legit to me.”

Once the ball was rolling, however, four more songs took shape, all of them more compact. Tom Sawyer, with its measured, deep groove, and the faster Red Barchetta were big on melody, anthemic in feel, even if both lacked a defined chorus. Limelight was based around a simple guitar riff but moved through subtle mood shifts – “some beautiful ups and downs”, as Lifeson put it. And in YYZ there was an instrumental as dramatic as the Overture from 2112.

The latter was mostly the work of Lee and Peart. “One day, Alex wasn’t around,” Lee said. “So Neil and I just went out to the barn and we started putting YYZ together as a bass and drum jam extravaganza. And then Al came in and added his licks, and before you knew it the song was finished.”

As Peart explained of the song’s title and percussive intro: “YYZ is the identity code used by Toronto International Airport, and the intro is taken from the Morse code which is sent out by the beacon there.” In the riff there was a sense of the energy of a buzzing big city airport. In the keyboard-driven mid-section, a sense of the emotions carried in passengers saying their hellos and goodbyes. And in Lifeson’s solo, what Peart described as an “Eastern mode”, a sound to evoke “the exotic nature of travel.”

YYZ was a brilliant construction, a story without words. But for Rush, more than any other rock band, lyrics were always as important as the music. It had been that way ever since Peart first joined the band in 1974; certainly, since he had taken inspiration from author Ayn Rand to create the dystopian sci-fi tale of 2112. And so it continued in the songs they wrote at Stony Lake.

From Pye Dubois’ original idea, and from Mark Twain’s classic 1876 novel The Adventures Of Tom Sawyer, Peart created a powerful declaration of independence. As Rolling Stone writer David Fricke saw it, Peart was “reimagining Mark Twain’s tearaway as a contemporary rogue with no fixed politics but a hunger for wonder”. And as Peart later revealed, this was in part autobiographical. The lyrics he took from Dubois were, he said: “A portrait of a modern day rebel, a free-spirited individualist striding through the world wide-eyed and purposeful.”

Peart then put his own spin on it. “I added the themes of reconciling the boy and man in myself,” he said. “And the difference between what people are and what others perceive them to be – namely me, I guess.”

These core principles – liberty, individualism, anti-authoritarianism – were also at the heart of Red Barchetta, for which Peart took inspiration from a short story by Richard S. Foster, titled A Nice Morning Drive. In Peart’s tale, set in a future where cars are outlawed, a defiant hero gets his kicks burning rubber in a vintage machine, a Ferrari 166, or Barchetta. There was, in this, an echo of 2112 – the hero in that story playing music banned by the rulers of a totalitarian regime. There was also a little personal detail in Red Barchetta. Peart loved fast cars, and this was a favourite model of his.

But if, in Tom Sawyer, he was making oblique reference to his own life, in Limelight he let it all out there. A sharp rise in the band’s profile had, for Peart, brought with it unwanted attention. Away from the stage, he remained protective of his private life. Faced with overzealous fans, he recoiled. As he remembered: “People chasing us around, coming to my house… I was shocked.”

Lines he wrote in Limelight – “One must put up barriers to keep oneself intact” – were reminiscent of what Roger Waters expressed in Pink Floyd’s The Wall, an album that resonated deeply with Peart.

“The Wall is my life story, too,” he said. “The alienation factor – all of us, as touring musicians, lived that. I once heard a DJ play a track from Wish You Were Here, one of the alienation songs that preceded The Wall. And the DJ said: ‘If you’re a songwriter and you write about what’s near to you, if you become alienated you’re going to write about being alienated.’ I totally understood that.”

Lee and Lifeson also understood where Peart was coming from. Lifeson said of the solo he played to fit the mood in Limelight: “It sounded haunting and very lonely.” And when Lee talked about this song, many years down the line, he explained the differences in personality that made him able to deal with fame in a way that Peart could not.

“Limelight came at a time when Neil was struggling, working out how to deal with it,” Lee said. “We all were going through it in our own way. Alex and I seemed to be able to block those things out. But Neil couldn’t. It was not in his nature to do that. When Neil wrote that lyric, we were getting more popular, it was a different level of fame, and Neil was being confronted with things on a regular basis that were making him really uncomfortable. So he wrote that lyric: ‘I can’t pretend a stranger is a long awaited friend.’ That song was Neil’s way of trying to sort it out. As frontman, you developed more armour: I was more ready to make a fool of myself on a nightly basis. Neil was a guy playing drums, so he was kind of protected. He had that battery around him. Like, he’s hiding behind there. They can’t find him.”

On August 31, the band returned to Toronto and to Phase One Studios to work with producer Terry Brown on demos of these five tracks, plus a first draft of work-in-progress, provisionally titled Witch Hunt. By Lee’s recollection, only one song written at this time was discarded, and while he could not recall why this song missed the cut for the album, its title – Sir Gawain And The Green Knight – was perhaps a little passé, a little too 1977 and A Farewell To Kings.

A short tour followed, just 16 shows around the Eastern US. Then, in October, they headed to Le Studio, in the small town of Morin Heights, up in the mountains outside of Quebec, to begin recording the album.

Le Studio was where they had made Permanent Waves, and as with Stony Lake, the remote and peaceful location was very much to their liking. “What a beautiful setting,” Lee said. “We all lived in a house a short walk from the studio, which was by a lake, and went there through the woods every day. It was very inspirational. Some people might wonder how such a tranquil setting could be a good thing when you’re making a hard rock album, but it worked for us.” Even so, he admitted: “We went back to Le Studio because we’d had such a great time making Permanent Waves, but Moving Pictures was a much more intense experience. It took quite a bit longer to make that record. For sure, it was not as easy as we would have liked.”

As Lee remembered it, Red Barchetta was the easiest song to get down on tape. “It was such a great thing to play live, off the floor,” he said. But other songs proved more problematic, the right feel more elusive: none more so than Tom Sawyer. “That was such a hard song to get right,” Lifeson said. “I remember spending a lot of time on that song. A lot of time…”

Some of that time was spent, as Lee recalled, “experimenting to get the right sounds” – first, for the bass pedal synthesizer in the intro, with what he called “that big, growling low-end”. But as he said: “The hardest thing of all was getting the right guitar sound in the solo section. We wanted that section to be played pretty much as a three-piece, not a whole lot of overdubs, but with a sound that filled up the stereo spectrum and didn’t sound empty. So the guitar sound for Alex’s solo was really critical. It wasn’t drowning in echo. That was the old trick we used in the past. If you want to fill the space, put an Echoplex on Alex and the repeats will fill up the space. But we didn’t want to do that. We were going for this dry sound with that unique tone, and for it not to feel empty, that was kind of hard. And even mixing that song was difficult.”

At one point, they almost gave up on it. “We always have one song, on every album, that doesn’t quite click,” Lee said. “And we thought that Tom Sawyer was going to be the one. Which just goes to show you we don’t know what we’re talking about!”

In the end, what Rush delivered in Tom Sawyer was a brilliant ensemble performance: the tension in Peart’s taut beats and explosive fills, the expressiveness in Lifeson’s solos, the heavy propulsion in Lee’s bass, and the nuances in his voice, singing high and low to dramatic effect. As Lee said: “After a lot of struggling, we nailed it, and it was so powerful. We were going, ‘Shit, where did that come from?’ That song was a late bloomer, but when we finally nailed it, we were so happy.”

There was less of a struggle with two songs that would be placed at the end of the album, Witch Hunt and Vital Signs. Lifeson said of Witch Hunt: “It’s kind of an oddball, but very dynamic.” Lee called it “an attempt at being cinematic, boldly illustrating a theme.”

Certainly it was the darkest and strangest song on the album, with an enigmatic subtitle – Part III of ‘Fear’. “It’s part of a cycle of songs,” Lee explained – a cycle that would be completed, albeit in muddled order, by The Weapon (Part II) on the 1982 album Signals, The Enemy Within (Part I) on 1984’s Grace Under Pressure, and Freeze (Part IV) on 2002’s Vapor Trails.

The subject of Witch Hunt was heavy. As Lee described it: “The effect that fear can have on a crowd or a mob.” But he remembered the fun they had in creating the song. “It involved some stupid stuff,” he said. “Recording the mob shouts, the three of us went out into the studio parking lot in the freezing cold of winter.”

Vital Signs, what became the final track on the album, was also the last to be written, and with surprising ease. “We needed one more song for the record,” Lee said, “and we wrote and recorded Vital Signs in one day. It was one of those happy, spontaneous things.”

In this song there was a flavour of new wave and, in the verses, the influence of The Police in a reggae rhythm – first utilized by Rush in The Spirit Of Radio, and later expanded into songs such as Digital Man and Distant Early Warning.

“With Vital Signs,” Lee said, “we felt that we needed something really different, something that was up-tempo and that had a more modern pop/rock vibe to it. It was kind of a nice way to end the record too.”

As Lifeson put it: “You’d think, looking at the songs, that something big like The Camera Eye would be the closer. But we went out on a different note with Vital Signs. It was an interesting way to finish.”

With that last song in the can, all that remained was the mixing. But if the writing and recording of Vital Signs seemed all too easy, this final process proved once again that for Rush, nothing was ever simple.

“During the mixing stage, things started to go wrong,” Lee said. “We were getting stuff happening that wasn’t supposed to be there. Terry Brown told us that the only thing we could do was shut the thing down, and get someone to fly over from England to fix it. The problem was traced to a faulty wire, and there was too much moisture in the earth, and it was giving us spikes in the mix.”

The mood within the camp turned from frustration to sadness on the night of December 8, as they were attempting to mix Witch Hunt. As Lee recalled: “This horrible news came over the wire, the news that John Lennon had been shot. We were sitting around the TV in shock. We were all so sad. That is something I will never forget.”

But as the days ticked down towards Christmas, the gloom eventually lifted. As Lee explained: “We did some of the mix in the old-fashioned way, manually. There were four pairs of hands on the desk, trying to get things done, because all of us were actively involved in all of the production. And it made it a lot more exciting. Using a computer was a little more distant. We loved getting our hands dirty.”

And while Lee would suffer a crisis of confidence once he got out of the studio and sat brooding over the album in the heat of the Caribbean, the doubts in his mind soon cleared. “After a good couple of weeks away from it,” he said, “I could listen to it and go, okay, it sounds pretty good!”

Moving Pictures was released on March 12, 1981, preceded by the first single, Tom Sawyer, on February 28. “At the time it was just another album in Rush’s history,” Lee said. “But this was the point at which we made a real transition musically and lyrically. People might say it was the birth of the modern Rush. I think it was a more gradual process than that. But this album was a very important one for us.” As Peart said, “We just made a record that we liked. That’s what we did all the time. But suddenly all of the stars were aligned.”

According to Lee, it was Peart who named the album while they were recording at Le Studio. “We always had the album title in our minds,” Lee said. “We wanted the whole vibe to be very cinematic. That was the concept. To have the music also telling the story of the lyrics.”

And from this came Peart’s idea for the album cover, for which Hugh Syme once again served as art director. “Neil certainly had a major input into the album sleeve,” Lee said. “He showed Hugh Syme, some early lyrics, so he’d get the feel for where we were coming from. Then Hugh came up with some ideas and showed these to Neil. When the two of them were happy, they brought it to Alex and me, so we also had a say.”

The image that Syme had created for the cover of Permanent Waves, featuring model Paula Turnbull, was in stark contrast to the heavy symbolism in his designs for previous Rush albums. Lee explained: “We were very aware that it was time to get away from the fantasy and science fiction elements that had always been part of what we were about. And as that musical side of things changed, so did our feelings of the way our album artwork should look.”

As with Permanent Waves, its cover filled with visual puns on the album’s title, so it was with Moving Pictures and Syme’s artfully staged photograph, shot at the entrance to the Ontario Legislative Building at Queen’s Park, Toronto. “I like the triple play on the sleeve with the words moving pictures,” Lee said “You’ve got the pictures literally being moved out of the building, then the old couple who were moved to tears because they’d dropped their shopping bag, and finally the film crew on the back cover, making a moving picture. It’s all to do with our sense of humour.”

Within a month of its release, Moving Pictures topped the Canadian chart and reached number three in the UK and also in the US, where it was beaten out of the top spot by two soft rock juggernauts, REO Speedwagon’s Hi Infidelity and Styx’s Paradise Theatre. The success of Moving Pictures also put new life into the band’s back catalogue, with 2112 and the live double All The World’s A Stage going platinum in its wake. At this juncture Rush reached a major career milestone, with more than ten million records sold worldwide.

Tom Sawyer was not a huge hit, peaking at number 24 on the Canadian chart, and number 44 in the US. Although a video for the track had been filmed at Le Studio – the bluish snowbound landscape visible through the windows as the band played – MTV was not launched until August 1 of that year.

But what really mattered, back then, was rock radio. And for that, Tom Sawyer was a perfect fit. As Cliff Burnstein, who worked with Rush at Mercury Records before co-managing bands such as Def Leppard and Metallica, put it: “Tom Sawyer became the anthemic track that Rush needed to become more than the biggest cult band in America. To become a band of mass cultural acceptance.”

In the words of Tom Sawyer there was so much that free thinkers could relate to: “His mind is not for rent to any god or government”. But there were two key lines – “The world is, the world is/Love and life are deep” – that made this song, for Burnstein and others like him, “a quintessential stoner anthem”.

Moving Pictures defined Rush in the 1980s as powerfully as 2112 had done in in the previous decade. If 2112 was the apogee of the band’s progressive rock era, Moving Pictures crystalized the modern Rush – in the clean lines and lean power of songs such as Tom Sawyer and Red Barchetta. But there was enough to carry long-term fans with them – echoes of the past in the grand scale of The Camera Eye, and the concept of Witch Hunt as part of a thematic song cycle. And there was in YYZ a perfect example of what Cliff Burnstein described as “pure Rush as musicians”.

“There are a lot of songs that just reached a standard on that record,” Lifeson said. “I think it’s some of our strongest, most enduring material. The songs were good, and they connected with a bigger audience. But there was also something about the sound of that record that resonated with people.”

Moving Pictures stands tall as the biggest and arguably the best Rush album. “That level of success was like nothing we had ever experienced before,” Lee said. “It was such a huge record for us. And the years have been very generous to it.”

Tom Sawyer, for all the difficulty in its creation, became the band’s signature song. This, for Peart, was astonishing. “It’s a wonderful thing,” he said, “that such a bizarre song could be so popular.”

And as for Limelight, the song in which the drummer signaled his retreat from fame, the message was not lost on Rush fans. They respected the honesty in those lyrics, and in turn respected his privacy in all the years that followed, right up to his death in 2020.

In 2011, before a concert in Birmingham, England, during the band’s Time Machine tour – on which they celebrated the 30th anniversary of Moving Pictures by performing the album in its entirety – Peart sat smoking in his backstage practice room and described the kind of encounter with fans that made him uncomfortable. “If you meet someone at the launderette and they go: ‘Oh, this is the greatest moment of my life!’” Laughing, he added: “I like the motto: ‘never complain, never explain’. But I can never resist trying to explain.”

Perhaps he had explained enough in Limelight, and as he said during that conversation in Birmingham, moments before he would go out and play that song again: “When I listen to early songs, I might cringe technically, but never psychologically or emotionally. My ability to express myself has grown and evolved. But I still mean every word of Limelight, however crudely it might have been expressed.”