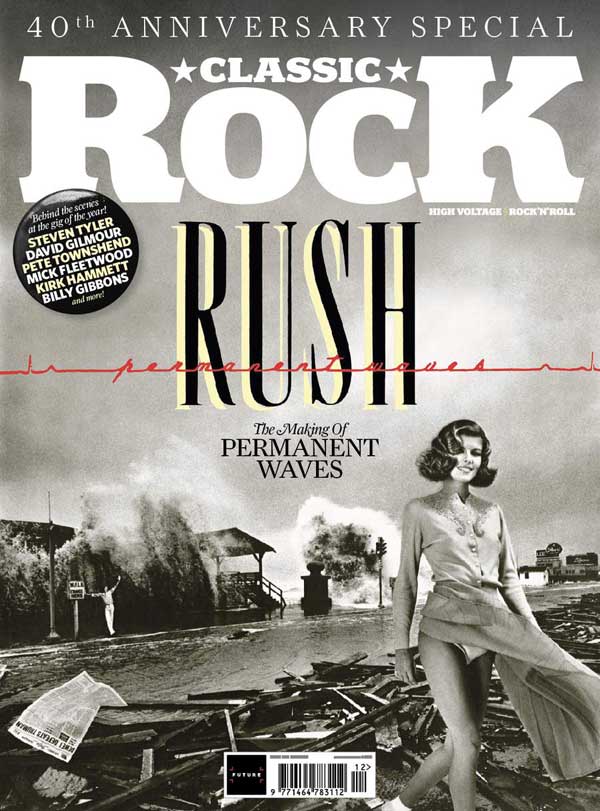

In 2020, Rush released the 40th anniversary edition of their classic album Permanent Waves. To celebrate the occasion, Classic Rock despatched writer and band confidante Philip Wilding to Toronto to speak with Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson about the album that saved Rush from themselves.

If you take the spiral staircase down to Geddy Lee’s basement studio in his Toronto home, you enter a veritable Aladdin’s cave with guitars and basses hanging from every available space on the tartan-covered walls.

Classic and obscure models in every conceivable colour make up a lacquered rainbow of instruments in a room where musical history has been made more than once. At the far corner of the room hangs a hand-tooled bass that holds almost as much history as this entire home studio: a pale Fender Jazz model with a Le Studio logo imprinted into its headstock.

Geddy takes it down from the wall and starts plucking abstractedly at its strings.

“This was gifted to me from a guy called Mike Bump and the Fender Custom Shop people,” he says. “The wood came from the door to the sound room at Le Studio. Alex [Lifeson] got aTelecaster and Neil [Peart] got a pair of drumsticks.

"I guess one of the ex-employees had contacted Fender and told them that this wood existed, and he took it upon himself to have it sent to Mike. We knew nothing about it, and so it was a very emotional thing when they arrived because all these memories of recording in that studio came flooding back.”

Le Studio, set on Lake Perry and in the foothills of the spectacular Laurentian Mountains (“It was truly a part of the great Canadian landscape,” says Geddy), not only marked a new decade and studio for Rush, but also an era when they would change the way they worked, how they wrote songs and, not to overstate things, their place in the world.

To understand how Rush were moving forward in 1980, you first have to go back to the tail end of the 1970s. After the relative ease of the recording of A Farewell To Kings, Rush returned to Rockfield Studios in Wales in the summer of 1978 – and hit a wall. Songs came slowly, creative energy was sapped, day became night, their working habits inverted.

“During Hemispheres we were like these monks,” says Lee. “At one point during that album we stopped shaving, we sort of turned into these fucking grotesque prog creatures in this farmhouse making this record, working all night, sleeping all day. Permanent Waves was quite the opposite.

“You have to remember that Hemispheres was the record that wouldn’t end. Everything about making that was exceedingly difficult. We were in Wales for far too long. I don’t remember more than three moments where we actually left the farm in over three months. We were very happy with the record, but it felt like we lost a chunk of ourselves in it.

“The other realisation I had was that I felt that we were becoming formulaic – these long, epic, side-long pieces were becoming inadvertently down pat; overture, theme here, repeat theme here… In and of itself, it was complex, but in actuality we were repeating ourselves, and I didn’t want to do that.

"So we concertedly tried to shift direction. You know: can we work in a seven-minute time frame? Can we put that limit on what we’re doing and see if we can make that more tuneful, more interesting and still complex? That was our goal.”

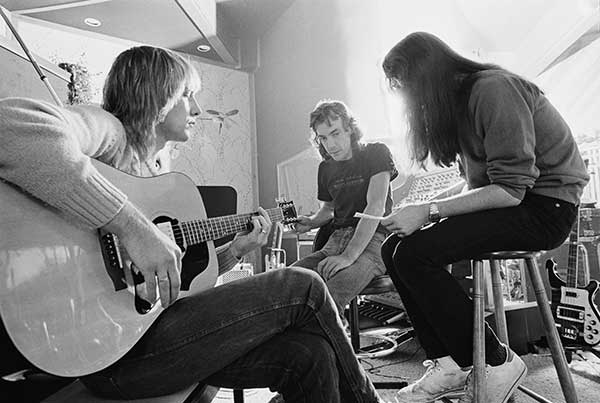

Ready to write in earnest for the next album, which would become Permanent Waves, Rush headed to the quiet solitude of northern Ontario (a regular thing for the band when getting ready to record a new album), this time settling into a cottage at a place called Windermere in the Muskokas.

They fleshed out some new ideas, tempered by the notion of bringing some brevity to their songwriting. “That’s the thing about Rush music though,” Lee says with a laugh, “five minutes feels like twenty.”

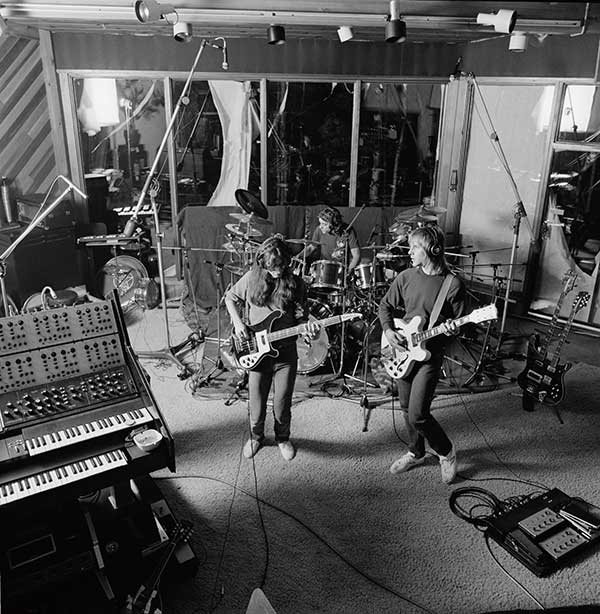

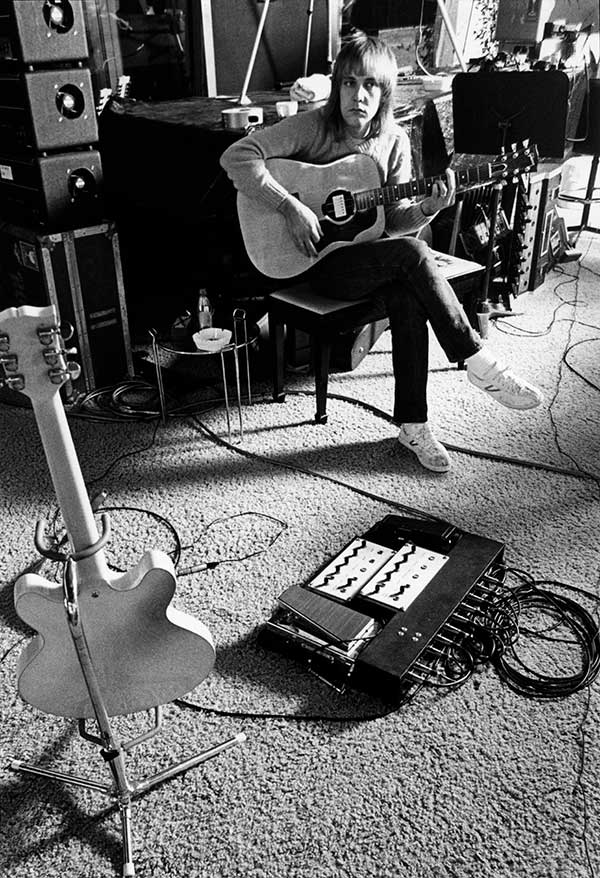

Lifeson, Lee and Peart set up home, with all the equipment they had brought with them filling the basement. Throughout the day, Lee and Lifeson would sit at either end of the sofa, the two of them trading riffs and ideas on acoustic guitars.

“We’d write all day,” recalls Lifeson, “and record our ideas on a cassette player while Neil worked on lyrics in his room. After dinner we would get together in the basement, with Neil’s drums taking up most of the space, and we would work on the arrangements as a band. Although [producer] Terry Brown didn’t move in with us, he did join us from time to time as the arrangements began to blossom.”

“I spent a few days up at Windermere with the boys doing pre-production,” Terry Brown tells Classic Rock. “That was time well spent. The guys might correct me on this, but I don’t think we did any writing in the studio, it had gone that well up the cottage. We would still be fine-tuning and making adjustments until we captured a take for the album, but most of that was happening in Le Studio.”

“We were very well-rehearsed and wellprepared. The songs were there,” says Lee. “We’d had really good writing sessions tucked away in that cottage. I have very strong memories of writing Spirit Of Radio and songs like that there, the two of us in the living room, hammering away at our acoustic guitars, and Neil appearing intermittently with his sheets of lyrics.”

“Spirit… stands out for me too,” says Lifeson. “But Freewill and Jacob’s Ladder do too, and that’s just side one. I think we were very pleased that our writing was moving in multiple directions yet carried the sonic stamp of us as players.”

“The strength of the songs and Alex starting his fascination with remote-control airplanes,” says Lee. “Those are my enduring memories of the cottage. As soon as we got a break from writing, he would go out and try to fly these planes. And of course they’d eventually get lost and we’d have to send out a search party for the plane! He carried his fanatical love of model aeroplanes to Le Studio, and we lost a few there too.”

Neil Peart visited the now near-derelict Le Studio in 2014 (a fire would destroy the site a few years later) and stood among the remains to reflect on the memories of his time there.

“It’s sad that’s it’s gone, and it’s especially sad that no rock band will enjoy that retreat,” he told George Stroumboulopoulos. “What it meant artistically and personally together, to work in the studio all day then go play volleyball at night. Those experiences, artistically and as a collaborative unit.”

Whatever magic was falling through the Canadian sky in the autumn of 1979 was turning into creative pay dirt for Rush. Each day unearthed some new gem. With all six songs already almost fully formed (this was Rush, so there was always going to be some tinkering), the band fine-tuned each one until it shone brilliantly.

“Freewill stands out the most for me,” says Lifeson. “It was such a challenging song to play for all of us, but I remember being so excited on the day we recorded it. I can still remember clearly sitting on the tall stool directly behind [engineer] Paul Northfield, with Terry at the console to my right smoking Gitanes.

"I’m sure we did Spirit Of Radio in the control room too, because that’s how we worked: on a stool, sitting behind Paul, with Terry there giving Paul a kick in the back of his chair every so often when he drifted away!”

Look back now at the photographs taken during those sessions, they show a band brimming with energy, each member laughing and at ease. Compared with the Herculean, energy-sapping task that was the making of Hemispheres, a band working in the dark and sleeping all day, making Permanent Waves was a relative breeze.

“It was the little things,” Lee recalls fondly. “We were more connected to our families – they were just hours away, not across the ocean – and we were in this beautiful, natural environment. The house we lived in was walking distance to the studio, through the forest every day. We were in this beautiful, natural environment. It was a more invigorating vibe. It was more spontaneous, and the album does reflect that energy.”

“At times, Hemispheres was soul crushing,” says Lifeson. “On the other hand, Permanent Waves was so positive and fun. We had come some way as a touring band, playing to larger and more supportive audiences, and all the touring made us better players. Individually we were all in a good space, and it showed in the way we treated each other and those around us. Life was fun and exciting."

No doubt in part due to their preparation, the band ended up recording Permanent Waves relatively quickly.

“Within six weeks we had the record sort of in the can,” remembers Lee. “Then we went to mix it in Trident, as that had been such a joy to work in even on the Hemispheres album. So we went back to London, and it was a magical mixing room and even the mix went very quickly. You never know what you get when got to make a record – you don’t know if it’s going to be a slog or if it’s going to be a treat. And Permanent Waves was a treat.”

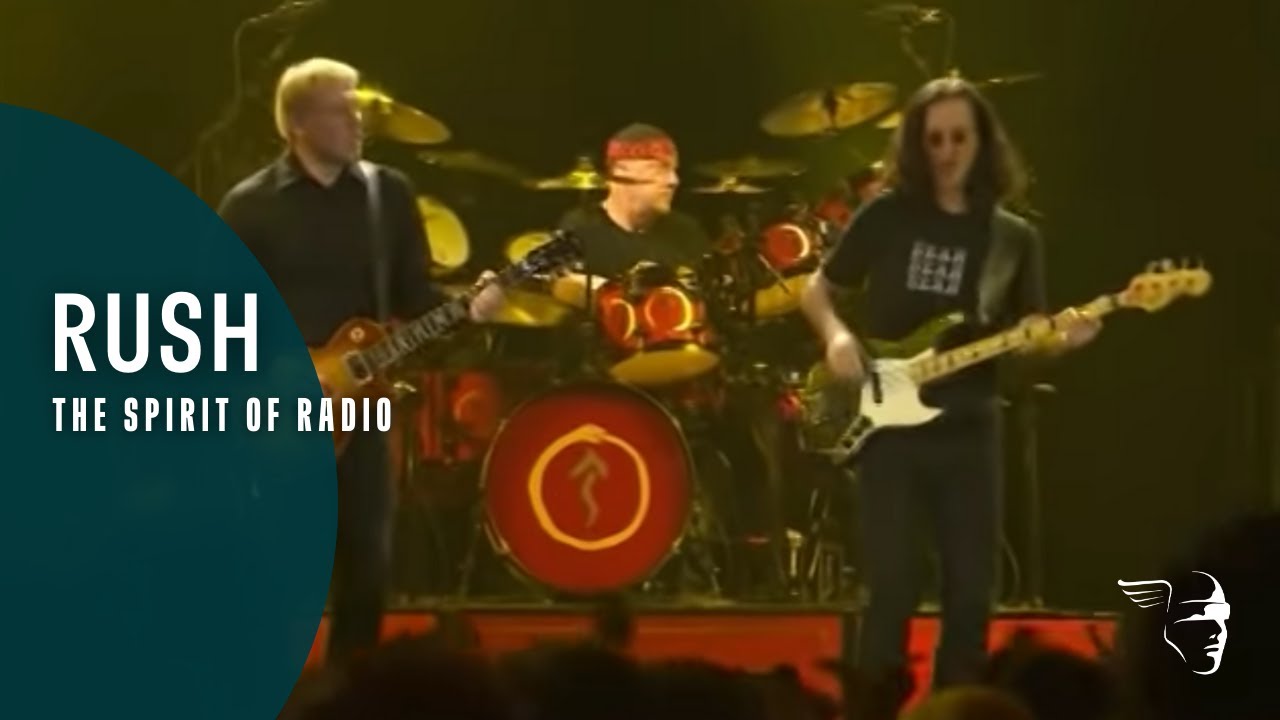

The band started the sessions with what would become the album’s opener and surprise hit record, The Spirit Of Radio. Lee talks fondly of how quickly it came together as a song up at the cottage, and as an opening track it’s so very Rush – a brilliant pealing guitar riff, a complex arrangement, a drum pattern you’d be hard-pushed to follow, and a reggae nod on the outro over a lyric railing against the commercialisation of modern-day radio.

Permanent Waves was so positive and fun. And all the touring made us better players. Life was fun and exciting

Alex Lifeson

If those sentences were about any other band, you’d be left scratching your head. Frame it as a reference to a Rush song, however, and it makes total sense. Because sometimes Rush really make no sense at all. Somehow they make the unworkable work. And never more so than on Permanent Waves.

“I think if you look through our history internationally,” says Lee, “Tom Sawyer probably has the most resonance and has garnered the most attention, followed by Spirit…, and then Closer To The Heart. Those are probably our three biggest individual songs.”

“I think we kicked off the sessions with The Spirit Of Radio, which excited me,” says Terry Brown. “It was something quite different and was fairly challenging, but as we zeroed in on the final performances it was obvious that it was something very special. I wouldn’t say any of our sessions were easy – the boys had a knack of challenging themselves on every record. Certainly The Spirit of Radio is a very challenging track to play and yet they make it sound so simple.”

“That song felt and sounded so positive,” says Lifeson. “It was one of those songs that seems to capture a moment in time. Not that we had any idea we were doing any capturing! But the response was strong, and we were happily surprised. You think: Spirit… was really a statement of where radio was going, where it had been."

“Growing up in the early 70s, FM radio was such a free forum for music. You’d have DJs who would play stuff for an hour. They’d just talk about the songs, there were no commercials or anything. Free-form, really – a platform for expanding music at the time. And then it was moving more towards a format, and away from that freedom. It was becoming more regulated, more about selling air time. It speaks about that, really.

“We wanted to give it something that gave it a sense of static – radio waves bouncing around, very electric. We had that sequence going underneath, and it was just really to try and get something that was sitting on top of it, that gave it that movement.” The Spirit Of Radio charted on both sides of the Atlantic, and set the tone, for sales at least, for Permanent Waves and the commercial peak that was to come.

“We’re always surprised when we have a hit anywhere,” Lifeson says with a laugh. “We’ve never really been a radio band. But, ironically, it made sense.”

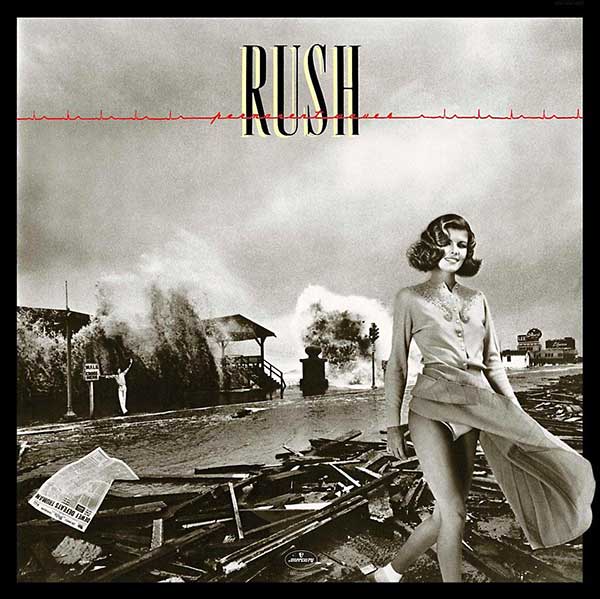

With Permanent Waves, it wasn’t just the band’s music that was being reshaped and reappraised. Who could forget the Hemispheres album cover: a naked man floating on a human brain, staring down a bowler-hatted figure lifted from a Magritte painting, as they both bobbed gently through time and space?

“When it came to the models for that cover,” says Hugh Syme, Rush’s long-standing art director and Neil Peart’s collaborative foil, “the Magritte man in bowler hat was my old friend Bobby King, also from the Niagara region where Neil and I both hailed from. The other figure was a dancer we found who was studying at the Toronto Ballet School.

“For my entire experience with Rush, never did they ‘pitch’ me, ” Syme continues. “Take Hemispheres, for example. I hadn’t even heard any music by then, as they were in Wales [at Rockfield Studios] for the album. Things got a little easier after that, when they started recording at Le Studio. I could fly or drive up to see the boys working, and that was much more convenient. I’d usually stay for about a week, and sometimes get invited to play on their records, something that had started on 2112 when I’d added some colour to Overture and Ged’s Tears.”

It was at one of those extended stays at Le Studio that Syme was invited to play piano on Different Strings, another new curve ball in Rush’s canon. With lyrics by Lee, it was plaintive yet rich. and examined the way in which the listener, or critic, consumed art and music. So far, so very Rush.

Its inclusion on the record hinted even more at the way the band were now willing to play with form and the sort of music people might yet expect from them. I tell Geddy that I had always assumed Different Strings was a simple love song coming from a very sincere place.

“No it’s not, actually,” he says. “That song was really born out of the idea that: here we were, this band that had been together for quite a long time and we had this ability to polarise people, our music did that. And in writing that song I was addressing that, about what we do and about art. And it really is about that individual way one reacts to it.

"Whether it’s music or visual or whatever, it’s an emotional response. It’s about our differences. It’s like Entre Nous and Different Strings are sort of two parts of the same concept. They are sister and brother.”

Different Strings aside, Hugh Syme wasn’t at Le Studio just to sample the charismatic sunsets and watch the light at play on the lake.

“Neil and Hugh used to deal with the cover designs,” says Lee. “I think Hugh used to take his cue from what he heard and read, and he would get bits of music and lyric sheets and he would take his image fix from that. And it was clear that we had turned a page. Remember, this was a period where everyone was talking about new wave; there was a new wave of pop and rock. In a way, the title of that album is a comment and a play on the words. There’s all those different wave images on the cover, and it was about the permanence of music.

“Not to sound pompous, but we really wanted to say that this new movement and new wave is exciting and everything, but rock’n’roll is here to stay, and there will be different waves and there will be different styles of it but it can never really be washed away.”

“Me and Neil spoke all evening about Rush growing up,” says Syme, “and how we were going to do these ECG [electrocardiogram] readers of each member as they were recording. So Permanent Waves was going to be a technical statement, and we were going to treat that with red and gold foil and do a nice study in design, as opposed to a photographic thing.

"Then – and I’m still not sure why – I said: ‘Let’s try something with a [model] walking out of a tidal wave situation.’ Neil gave me this blank look and said: ‘Get out of here.’ But the following day he asked me to consider doing just that.”

Syme ran riot. Against a background shot of the Galveston Seawall in Texas during Hurricane Carla in 1961, he superimposed Canadian model Paula Turnbull flashing her knickers and sporting a permanent-wave hairdo that looked like it could weather any storm. Hugh gave himself a walk-on part – waving happily in the distance. The band’s surnames were referenced on a rain-lashed signpost.

When the Chicago Daily Tribune railed against their newspaper being blown about in the foreground with the infamous front page from 1948 (when the paper wrongly reported the result of the US presidential election as ‘Dewey Defeats Truman’), the threat of legal action resulted in the headline being obscured on all but the earliest pressings of the album. All things considered, it was a long way from the brains and buttocks that made up the central image of Rush’s previous album.

You only have to look at the structure and form of the six songs that make up Permanent Waves to realise this latest journey the band were on. Much like Syme having some fun with the album’s cover, Rush were determined to break out of some of their own, self-imposed, shackles.

“That’s exactly what we wanted to do,” says Lee. “We wanted to do something different. Even the longer songs – and there are a couple of profoundly important longer songs in our history. But songs like Natural Science and Jacob’s Ladder are on there too, right? So those two are both indicative of what I’m taking about.

"They’re quite different, and again they’re long concepts, but contained in a ten-minute time frame, as opposed to dragging this concept over a side-long thing. We didn’t feel that Jacob’s Ladder was profound enough to be a one-side thing, you know? And over the years our affection for that song has grown, largely because of how much affection our fans have shown it.”

Are you saying you weren’t originally a fan of Jacob’s Ladder? That’s like hearing that Stephen King doesn’t like books about horror.

“Ha! I guess it was hard for us to tell how different it was at that time,” Lee says. “We played it initially on the first couple of tours and then we stopped playing it for a while. We lost interest in it. But it was constantly one of the top five requested songs from fans for us to bring back into the live show. We resisted that until the last R40 tour when we did bring it back.

"I was really not thrilled with the idea of playing it. The other guys were up for it, and I wasn’t until we were in rehearsals, where I went: okay, now I remember what I liked about this song. So I got back into that head space for it. And then during the last tour I enjoyed the hell out of playing it. We all did. It was clearly a highlight of the show. It’s got those great, relentless signature moments that Rush fans love so much!”

The album and the single Spirit… propelled Rush up the charts. It was their biggest-selling record to date, and would be surpassed only by the album that followed, Moving Pictures.

“I think the decision to stop the concept album thing was big,” Lee says. “To put a pause on the whole concept, and to look at writing as a series of individual concepts – a series of smaller movies, in a way, which is what led to Moving Pictures. The energy of Permanent Waves bled into Moving Pictures for a number of reasons. And the fact that Permanent Waves was received so well was really a huge boost to us, from a confidence point of view… Every time in life you try something different and it’s well received, that’s about the greatest reward you can have.”

Lifeson agrees with Lee about the domino effect that Permanent Waves had on the band and their subsequent career: “That is true,” he says. “It was very much like that. Moving Pictures is the cute, sweet, happy offspring [of Permanent Waves]. We learned a lot about writing and how we work best to accomplish our goals, so that an ambitious album such as Moving Pictures could be made without wanting to kill ourselves.”

That’s the thing about Rush music though: five minutes feels like twenty

Geddy Lee

Such was the band’s momentum that they canned the idea of releasing a live album off the back of what had become their most successful tour, and headed into the Canadian countryside and back to Le Studio, a place they’d call home, off and on, for more than a decade.

“We were scheduled to do this big live album after Permanent Waves [it would eventually appear as Exit Stage Left, after Moving Pictures was released] and at the last minute we said: ‘You know what? Fuck this, we’re not going to do a live album, we’re going to go back into the studio and do our next album’,” recalls Lee. “And that’s how Moving Pictures came to be.

"It rode the wave of exuberance that we found through making Permanent Waves. And it turned out to be the most important decision of our careers. Or the second most important decision. The first one being 2112, because without 2112 there would be no Rush.

“If you look at our zig-zag history, we sort of started as a heavy rock band, and then with the addition of Neil and Fly By Night [1975] we realised we finally had a third member that had progressive thinking, that confirmed our progressive tendencies. And that’s why you see what began on Fly By Night reach its apogee on 2112, and we developed that once we had found our style. That style worked itself to the end of Hemispheres, and then it was time to change.

"In a way it [Permanent Waves] was really the beginning of our third period. The second period was once we had established who we were, and created our own voice.”

Alex Lifeson and I are reminiscing just before our conversation ends. I once got to stand on stage with Rush as they played The Spirit Of Radio, a song I vividly remember buying as a single all those years before as a teenage boy, and both those events still thrill me to this day.

“Isn’t it great, it still moves you now?” he says “That’s the thing, I have such fond memories of that time, so hearing those songs transports me to then. Isn’t that the amazing thing about music and how it marks different stages in one’s life? To be moved and reminded of a time forty years ago and to smile as I am now is a great blessing.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 274 (May 2020). Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson are exclusively interviewed in the new issue of Classic Rock, out now.