“The first time I ever got high was with Alex. He was just a terrific pothead, and a terrible influence on me”: The chaotic story of Rush’s early years and their journey from high school stoners to prog icons

Rush’s Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson look back their journey from high school stoners to prog icons-in-waiting

All great things have to begin somewhere. For Rush, that somewhere was Willowdale, a suburb of the Canadian city of Toronto. That was where Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee met as schoolkids - the start of an enduring friendship and musical partnership. In 2012, as the band released their swansong album Clockwork Angels, the pair looked back on story of the band’s formative years: their school days and early adventures in music, the struggle to make it, the difficult birth of the first Rush album, the tough decision to fire original drummer John Rutsey, and how the subsequent arrival of Neil Peart – drummer and lyricist – completed the classic Rush line-up that survives to this day.

Alex Lifeson: I met Geddy when were thirteen years old, in our first year in junior high school. We were aliens in a class of conformity, and we became best friends.

Geddy Lee: At school we had a blast together – we cracked each other up. And we understood where each other came from, culturally. We were sons of Eastern European immigrants who had left Europe after the Second World War to start a new life in Canada. So we were, both of us, a little bit different.

Alex: I’m first generation Canadian. Both my parents were Serbian, so of course my birth name was Serbian – Aleksandar Živojinovi. My parents actually met in Canada after the war. They had come over as refugees. My father had been married before, to a Serbian woman. They had married in Italy, and my sister was born there. They tried to get into the States, but they were denied and then sent to Canada.

Geddy: My parents were Polish Jews, survivors of the Holocaust. They met when they were thirteen at a work camp and they were both in Auschwitz for a time. My mom had such a strong Jewish accent, which is how I ended up being known as Geddy instead of Gary, my real name And basically, it stuck. Eventually my family was calling me Geddy. So a little later, when I turned sixteen, I legally changed my name to Geddy, because so many people were calling me that anyway.

Alex: It was at junior high, in that ‘getting to know you’ stage, that Geddy and I got heavily into music.

Geddy: We wanted to be rebellious, to break away from our families, like all kids want to do. And we both had a really deep passion for music and wanting to play it. Almost every day we’d go to his parents’ place after school and we’d jam for two hours.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Alex: For a long time we were in different bands, but we always jammed together. We loved to learn all those great Cream songs, play along to the record player, and play them better and better and better. It was really a lot of fun. It was just the two of us – no drummer. We’d either play along with the record, or we would both plug into Ged’s amp and just play, him on bass, me on guitar. We were beginning to look at music more seriously and really trying to figure out what the musicians were playing, how the bands worked. And we loved to play. We just couldn’t get away from it.

Geddy: The first time I ever got high was with Alex. He was just a terrific pothead, and a terrible influence on me. We went to the local public school grounds to smoke some pot. At that time I was playing in another band, and after I got high with Al, I went over to the guy in my band’s house for rehearsal. But I was a little too high to be very functional, and this guy was really mad at me. He was very straight and he was really upset with me. He was threatening to tell my mother that I was high. That was a bummer!

Alex: I had a friend named John Rutsey who played drums, and we had a little basement band called The Projection. The guy that lived next door to me, Gary Cooper, was the bass player. Gary didn’t stick around for long. But out of The Projection came the first gig as Rush. John’s brother Bill had said, ‘You need a better name for the band – how about Rush?’ And we liked it. We were offered this gig at a drop-in centre, so I called this guy I’d been jamming with, Jeff Jones, who played bass and sang. We did that gig. Twenty people showed up. The following week we were offered another gig at the same place, but Jeff said he couldn’t do it – he was already in another band at the time. So that’s when I called Geddy.

Geddy: I was a pretty shy kid. I didn’t really want to be a frontman. I was just the one with the best voice – or the most appropriate voice! So stepping out in front was not a natural thing for me. John was the leader of the band, to all intents and purposes. He was a very opinionated guy – about music, about what he thought the band should be, how we should look.

Alex: For a couple of years we just needed to learn our trade. At that time you played maybe three times a month if you were really lucky, at high school dances and drop-in centres. After a year playing clubs, the shows were packed. We were making a thousand dollars a week. Back then, that was good money.

Geddy: The problem was that when it came to making an album, nobody had even the slightest interest in signing us. There was no big rock label in Canada. Really, there were just distributor outposts for the American companies. And nobody cared anything about Canadian music.

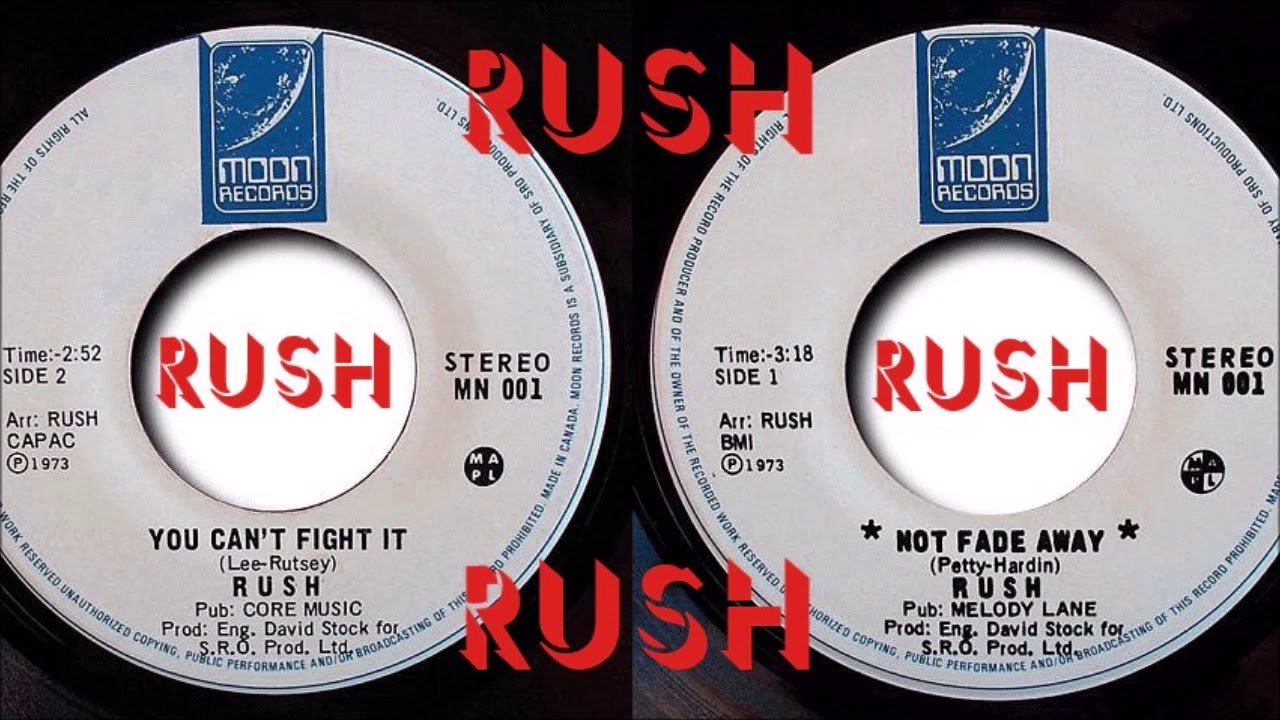

Alex: We made a single, a cover of Not Fade Away – based more on the Stones’ version than the Buddy Holly original. The feeling from management was: let’s do something that people will get as an introduction. I think that was bad advice. Playing that song live was great. We played it quite heavy. It sounded really good. But the recorded version was terrible.

Geddy: I was so excited about doing a record and having our name on the disc, the whole deal. But to be honest, I was embarrassed by how it came out. It was so… dinky.

Alex: We were a hard rock band. We had some powerful songs – Working Man, What You’re Doing. But that record sounded so tame.

Geddy: It was so disappointing. But our manager Ray Danniels put up the money for us to make an album. We had to do it cheap, recording late at night, after hours. The problem was that our producer, David Stock, was just not that great. So we had to record that album twice. The first version had Not Fade Away on it, and the whole thing sounded as tinny and shitty as the single did. So we had to redo the entire album, and that’s when Terry Brown came in as producer.

Alex: Terry had a studio, Toronto Sound. And once we got in there with him, I think we spent another three days recording, so that whole album was done in about a week.

Geddy: It was pretty straightforward – it was only eight-track recording. And at the time, we were playing these songs a million times over and over, so it wasn’t a big deal to go in and re-record them. Terry really fixed that record. It sounded great. We were very proud of it.

Alex: The album came out on Moon Records, the label that our manager set up. The big turning point was when Working Man got picked up on a radio station in Cleveland, Ohio – WMMS. That was a time, 1974, when FM radio was still based on the DJs’ tastes.

Geddy: It was a very different time, before the consultants took over American radio. So you hear a song like Working Man, seven minutes long, on the radio. And that led to us singing with Mercury Records. Whether that deal would have come some other way, who knows? But certainly that was the breakout.

Alex: We knew early on that John had problems with his health. He had diabetes, and he was very concerned about whether it would be manageable for him on the road. In 1974, John got ill and missed out a few months of gigs. We used another drummer, Jerry Fielding, and then John came back for a month of club shows. But that was it for John. We had to fire him.

Geddy: That was hard. It was clear that there was going to be a break with John sooner or later. What he wanted to do as a musician and what we wanted to do as musicians was not the same, and eventually that would have caused the band to break. We were guilt-ridden at first, but we realised that it’s just the way it had to be. He wasn’t happy and we weren’t happy. He had personal issues. It was a complicated time. We were discussing a future and not knowing what that meant. The rehearsals were becoming not much fun. There were definitely two different views in the band.

Alex: Ged and I were listening to more progressive music – Yes and Pink Floyd. We wanted to work that into our music. John was more of a straight rocker. So we were kind of relieved that John was gone, but it felt weird without him there as we started auditioning new drummers.

Geddy: On the day that Neil (Peart) auditioned, we had five guys in – three before Neil and one after. The last guy had come a long way, a two-hour drive, and it was a very uncomfortable situation having him audition after Neil, because Neil was so fucking good. This poor guy had written charts and was playing our songs to charts. We were going through the motions. It was really awkward. I’m looking at Alex and Alex is looking at me. We were embarrassed for this guy because we were both so excited by Neil’s playing. There was no denying that Neil was the man.

Alex: We were so blown away by Neil’s playing. It was very Keith Moon-like, very active, and he hit his drums so hard. And then after we’d jammed, we chatted and he was so bright. We connected on many levels. I have to admit that on that first day I said to Geddy, ‘You know, maybe we should still hold out and see who else is out there.’ But when we talked again we were convinced he was the right guy.

Geddy: The first thing that we jammed with Neil in his audition was Anthem. That song was written, for the most part, while John was still in the band. It was very different to any of the songs on the first album – more complex. There were a lot of things that John was unhappy about, and one of them was the direction that Alex and I wanted to go in. And I think with that little bit of Anthem, our musical differences were sort of brought to the fore.

Alex: As soon as Neil was in the band, we started writing new material. We worked on most of the songs together in those days. But we were touring all the time back then, so we didn’t have any time to go anywhere and write. We were writing on the road, in the backs of cars, going to gigs, dressing rooms. And it was still experimental for us. We were still feeling each other out.

Geddy: We were still an opening act at that time, and the one beautiful thing about being an opening act is you just have thirty five minutes to play. You don’t need a show. It’s all about your chops and trying to impress in thirty-five minutes. And when you’re done, you have plenty of time to jam and to write.

Alex: What we needed was somebody to write lyrics…

Geddy: We kind of pushed Neil into writing lyrics. A lot of the songs on the first album, John had written the lyrics. But when we were on the road, we saw Neil reading books all the time. We thought, this guy is pretty smart. And the bottom line was, Alex and I didn’t want to write lyrics. So we gently encouraged Neil to do it. And what he wrote was so cool, so different to the kind of stuff that John had written.

Alex: In many ways, the second album (1975’s Fly By Night) felt like a new start for the band.

Geddy: Anthem was a holdover. Pretty much everything else on that album was written fresh. With a lot of the songs on that record, the music came first. But sometimes, Neil would have a lyric and Alex and I would put the music to it. One song that happened like that was Beneath, Between & Behind, which was the first lyric that Neil wrote for the band. There was also a lot of diversity on Fly By Night, much more than on the first album. We had the heavy songs like Anthem, but we also had that really long quiet song Rivendell, which was our first attempt at showing the lighter, ballad-y side of Rush. We liked having a bunch of different styles on that record, and that diversity was something that carried on through every album. We wanted each song to show another side to the band.

Alex: We had some cool songs on that record. Anthem was really powerful. And of course there was By-Tor & The Snow Dog, which became a really big song in the development of the band.

Geddy: The lyrics that Neil wrote for By-Tor & The Snow Dog were very tongue-in-cheek. There was a kind of comic lexicon that we had on the road – a bunch of stuff that we would joke about. And that’s where By-Tor & The Snow Dog came from. It was a joke that got out of control. Our manager Ray had two dogs, and Howard Ungerleider, our lighting guy, called them Biter and Snow Dog. So Neil took these two names and created fictional characters and we turned it into a song.

Alex: By-Tor & The Snow Dog was the first time that we tried to do a whole multi-parted piece of music. It was a pivotal song for the band. And as we developed there were bigger concepts and more space to play.

Geddy: Suddenly, it was a very different band. Once we had Neil with us, so much changed in the way we wrote music and the way we presented it. And from that point on, it felt like we could do anything…

Alex: When we finished [1975’s] Caress Of Steel we were so proud of it. We really felt like we were taking some chances and growing and going somewhere. We were experimenting.

Geddy: The problem was that nobody really understood what the hell we were doing with that record. And I can’t say we really knew what the hell we were up to either. These long songs we had – The Necromancer and The Fountain Of Lamneth – they were very complex and dark. On The Fountain Of Lamneth were talking about Didacts And Narpets. It was kind of hard for people to understand.

Alex: The intent was always pure. Maybe the execution was not. But the last time I listened to Caress Of Steel, it reminded me of how important that record was to us at that time. We really loved that record. That’s why it was really painful for us to go on the road and see that there wasn’t any interest.

Geddy: It was very disappointing. At that point, we didn’t possess the requisite objectivity to know how much was wrong with Caress Of Steel. We didn’t understand why it had failed so badly. That really shakes your confidence.

Alex: We called it the Down The Tube tour. Everybody was in a state of panic.

Geddy: When you’re in a band and you insulate yourself from reality through your sense of humour and your camaraderie. You prop each other up and say, ‘Yeah, we’re probably going down the tube.’ But really, we were so confused and disheartened.

Alex: At least we had fun touring with Kiss. I remember Gene (Simmons) telling a funny story about that tour. Gene never took drugs, but one night in Detroit he was hanging out with us, and he accidentally he ate a hash cookie. He ended up so hungry, he had to go eat. He told me later, ‘We walked in a restaurant and my head felt like it was the size of a billiard ball and my voice was the loudest thing in the room as I was asking for a sandwich…’

Geddy: After Caress Of Steel flopped, the record company made it very clear to us that we were disappointing them – that we were not delivering on our promise as an up and coming band. But at least we still had a contract, so we knew we would get one more album that they had to release before we went down the pan completely. We figured we’d be dropped if the next record didn’t do well. Deep down, I think we were all convinced that our careers were over and we would have to get ‘real’ jobs. So 2112 saved our career. There’s no question about that.

Originally published online in 2015

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”