Ronnie James Dio found himself in a period of transition as the 1980s cranked into gear. Having jumped ship from Rainbow in 1979, while looking for a new gig he bumped into Tony Iommi at Sunset Strip's Rainbow bar and was invited to join Black Sabbath in place of a fired Ozzy Osbourne the same year.

While the creative partnership seemed a perfect fit at first – and produced Sabbath classic Heaven And Hell in 1980 – by the time it came to record their 10th studio album, 1981's Mob Rules, fractures had already started to appear within the group.

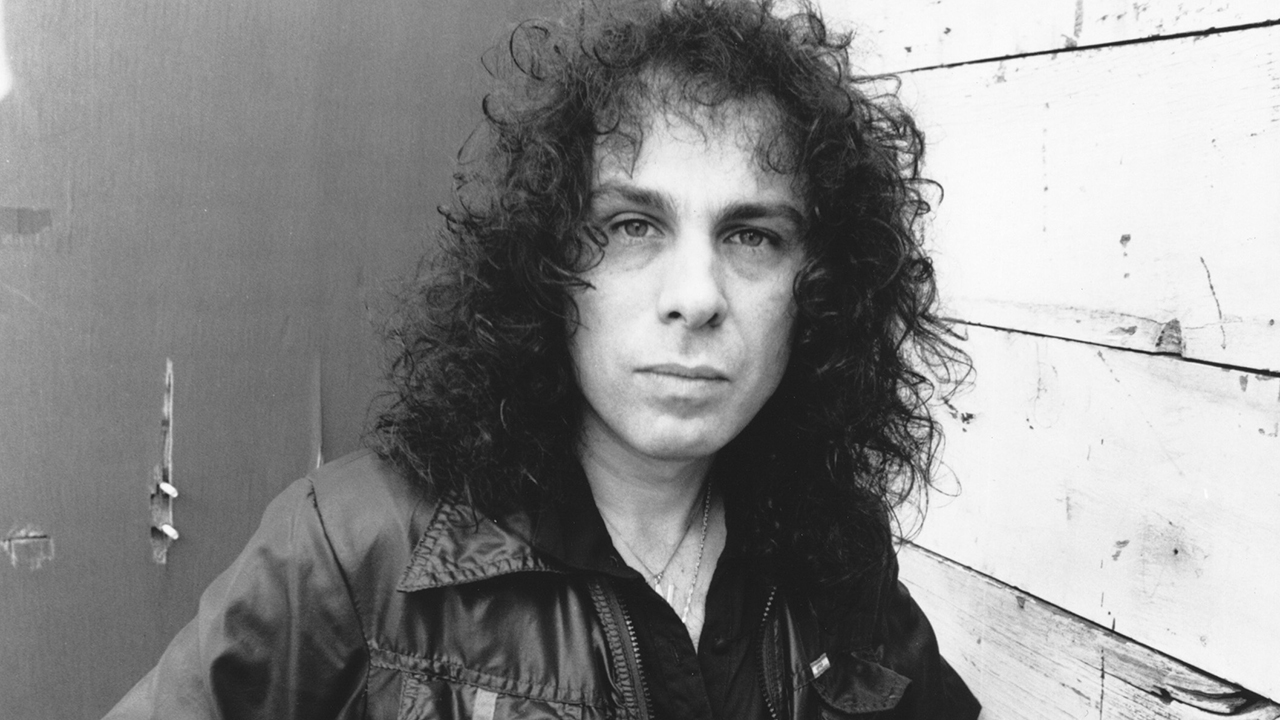

In this excerpt from his posthumous autobiography – titled Rainbow In The Dark, edited by Mick Wall and available to buy now – Dio shares the secrets of how Mob Rules really came to be.

One dream that did come true for me was when Sabbath headlined Madison Square Garden in October. I thought of those days twenty years and several lifetimes ago, when I would walk past the Garden, look up at whatever name was on the marquee, and fantasize about seeing my own name up there. I still didn’t actually have my name up there, but my band did.

19,900 people showed up, and it was named the top grossing show in the US for that week according to Billboard. I finally got to sing at MSG. The show itself wasn’t perfect. I remember having a row backstage with Sandy Pearlman, but that was all forgotten once I was on stage. It was a big moment for me.

It was great also to be in the band for their first ever tour of Japan. With Rainbow I’d gotten used to headlining to 15,000 at the Budokan. With Sabbath we did a string of smaller halls in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka. Then we did a week of similar-sized shows in Sydney.

We fired Sandy not long after, and I assumed the management role until we could figure something out when the tour was over. It was around this time I got my reputation for throwing my weight around. It was true, I did become much more assertive. I needed to be. Sabbath was a ghost ship when I joined. They desperately needed a captain, and I was more than happy to take on that responsibility, before I realized just how deep some of the problems went and how unfixable some of them would prove to be.

Meanwhile, we had a second album to record. For the first one, Tony and I wrote in a controlled environment in a living room with little amplifiers. We approached the writing much differently for this one. We hired a studio, turned up as loud as possible, and smashed through it all. You could say it made for a different kind of attitude.

Geezer was now involved and almost inevitably it changed the chemistry Tony and I had enjoyed working alone. It became obvious that Geezer wanted to be involved again in the writing of the lyrics. Throughout the Ozzy era, although Ozzy came up with his own vocal melodies, Geezer almost always penned the lyrics. You only have to scan the lyrics of classics like War Pigs or Children Of The Grave to appreciate how good Geezer is, but I had written all the lyrics on Heaven And Hell, and I had always written my own lyrics. I never needed a co-writer. I didn’t need one now. Geezer and I were friends, but this is where I had come in with Tony and Sabbath: I brought the voice, the vocal melodies, and the words. This drove a wedge between us. We would eventually get past it, but for now it was a wound that steadfastly refused to fully heal.

Tony affected not to notice any change. He had known and worked with Geezer for his entire career; they obviously had a much deeper bond. That had not mattered when we first started writing together. And while we still worked well together, I felt Tony moving away from me—just a little at first then, later, a lot.

Tony’s beef concerned a solo deal I had recently signed. After the success of Heaven And Hell, the band was able to renegotiate a better deal with our record companies, Warner Bros. in America and Polygram in Europe. The deal they came up with included the offer of a solo deal for me. It wasn’t a big money deal and there was no discussion of trying to turn me into a solo star. It was a sweetheart deal that was supposed to give me the room to make my own album at some point in the future, somewhere between Sabbath commitments. My first thought was to make an album featuring me with all my friends, like Kerry Livgren from Kansas, the Elf guys, David Stone, Skunk Baxter, and other people I’d been jamming with before I met Tony. It was going be a fun album, one day. Tony didn’t see it that way. I think he thought the offer of the album was divisive and he seemed pretty livid with me.

The first track we recorded was The Mob Rules, which is what we eventually called the album. Tony and I had come up with one of our best rockers at John Lennon’s former country estate, Tittenhurst Park, near Ascot: the famous white house in which they made and filmed the Imagine album. We were just jamming on ideas for a track we’d been invited to do for the soundtrack of a forthcoming animated movie, Heavy Metal, starring John Candy. The movie would bomb, but the track was hotter than a pistol.

We did the rest of the album at the Record Plant in LA. Martin was producing again and there was great energy to a lot of the music, but we couldn’t quite escape the idea that this was the follow-up to Heaven And Hell and we had a lot to live up to. I admit Turn Up The Night was a subconscious attempt to create Neon Knights part two. Voodoo was conceived somewhat as this album’s Children Of The Sea. The best track was Sign Of The Southern Cross, which for me was one of the best things we ever did, up there with Heaven And Hell, maybe even higher.

When Mob Rules was released in November 1981 it didn’t quite replicate the success of its predecessor, hitting Number 12 in Britain and again making the Top 30 in America. Reviews were more mixed. Those that liked it really liked it. Those that didn’t get it just kind of shrugged. For me, it remains one of the best albums I’ve ever done. Back on tour, Sabbath was as in demand as before. We did another Madison Square Garden show and we sold out the LA Arena and the LA Forum. We toured from November 1980 until August 1981, mostly in America. We were on a roll. By the end of it, however, I felt we were rolling in the wrong direction and might crash.

I was feeling increasingly alienated from Tony and Geezer. I liked to smoke pot occasionally and drink a beer, but I didn’t do coke and had no time for hard drugs. Tony and I may have hit it off when we were jamming or writing together, but socially we were now poles apart. Vinny was now my best pal. He was from Brooklyn. We were both New Yorkers. We liked a lot of the same foods. By the end of the tour, Vinny and I would ride off in one car after a show, and Geezer and Tony would ride off in another.

Rainbow In The Dark: The Autobiography, edited by Mick Wall, is available now