Surely I'm not alone in having found heavy metal artwork terrifying as a kid. The pictures of ghouls, gore and leering skeletons that covered the walls of my older step-brother's room were more than enough to keep me from sneaking into his bedroom and playing on his drums. For a small child who thought the Wombles were a bit scary, this was truly the stuff of nightmares.

These days, as a grown-up metal fan, I’ve learned to accept that grisly images and dark themes are an inseparable part of the subculture I love. But, for many of us, it has been a journey of acceptance to get there, and sometimes a wonder we got there at all.

Why does loud, heavy music so often go hand in hand with stomach-churning images and disturbing themes? Where did the darkness come from? And why do the fans love it so much?

A Spark in the Dark

Black Sabbath seems like a logical place to start. Arguably the first real metal band, they named themselves after a horror b-movie and latched onto the occult as a theme for their lyrics and artwork. It set a template for much that was to come.

At the time, the idea of the devil working through music was not a new one. Rock'n'roll had already been tagged ‘the devil’s music’, the myth of bluesman Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil was a few decades old, and the concept of the ‘devil’s chord’ had been around for centuries. Still, in the peace, love and flower power of the 1960s, Sabbath were a refreshing alternative. And, at this point, the devilry was still just a bit of fun.

As the fans started to drink it up, the spectacle got more extreme. As rock'n'roll flounced into the seventies, a preacher’s son named Vincent Furnier entered the mainstream. Furnier turned his religious upbringing on his head, transforming himself into an on-stage pantomime baddie called Alice Cooper. The crowds went wild for it, famously tearing apart a live chicken Cooper had thrown into the crowd.

So far, so theatrical. It was clearly a release for fans, mostly young people who were fed up of being confined by rules imposed by the authority figures in their lives. This new breed of ‘shock rock’ offered them the chance to form a new identity, whilst parents, conservative friends and curious younger siblings were all horrified enough to keep a safe distance.

And, of course, it was great for bands looking to make a splash with their performances and crank up record sales. But from as early as the 1970s, some bands were starting to take the ideas further.

Stairway to Hell

Karl Spracklen, Professor of Sociology of Music, Leisure and Culture at Leeds Beckett University, is the author of several papers exploring music counter-culture and so-called ‘dark leisure’.

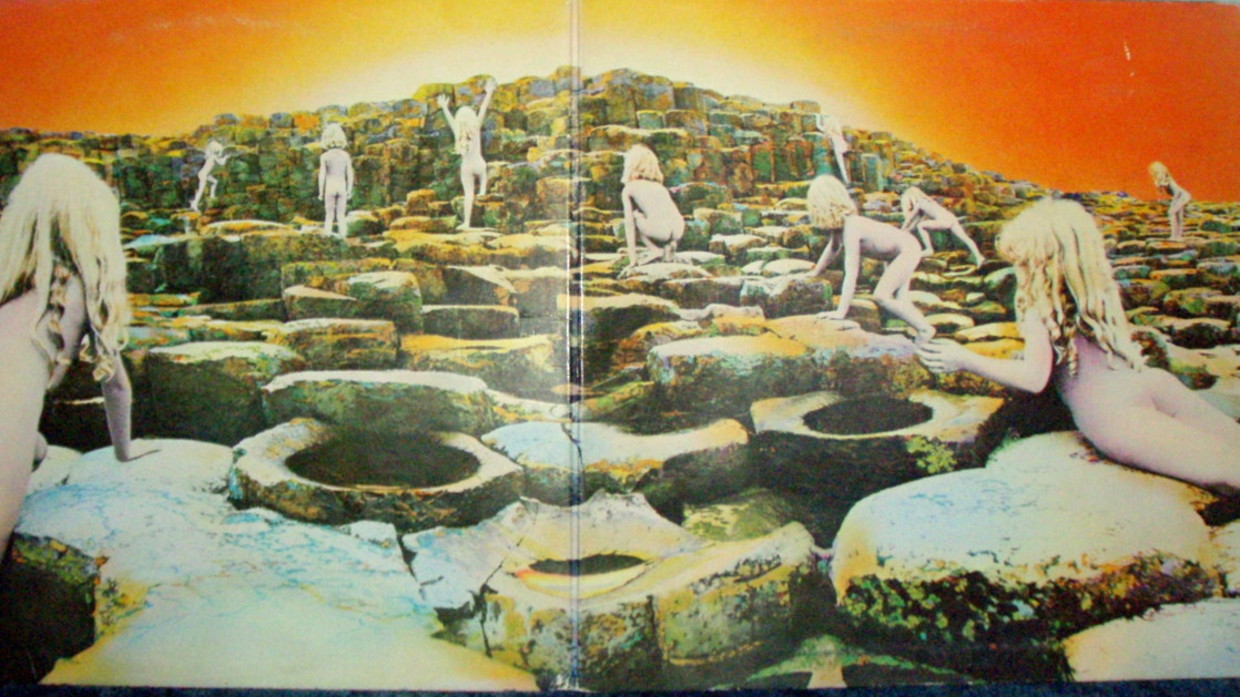

Spracklen identifies Led Zeppelin as a point at which we can observe metal and genuine occultism beginning to intersect: “These days you think of them as a classic rock band, but at the time they fell into the heavy metal bracket. And Jimmy Page took the darkness seriously.”

Page developed an interest in Aleister Crowley as a teenager, owned an occult bookshop in London in the 1970s and famously purchased Crowley’s Boleskine House, which was alleged to be haunted. Page was unlikely to have been a full-blown Satanist, but he clearly had an interest in alternative ways of thinking. This was less about marketing gimmicks, and more about darkness as a central part of an artist’s identity.

"There’s no doubt that metal fans stand together in a shadow of strangeness"

Then the 1980s dawned, and the lines began to blur. Who was playing at it and who was for real?

Spracklen explains: “If you look at Maiden’s The Number Of The Beast, once Bruce Dickinson is on board, they’ve seen what Sabbath and other bands before them have done and they’ve built on it. The album cover has a demon on it, and the title track is explicitly about the devil. For the fans, it’s about scaring their parents and teachers. It became a way for secular people to distance themselves from Christianity in the USA and parts of Europe where it was still strong. But the band weren’t Satanists, it was all just play.

“However, in the 1980s you also have bands starting to take those ideas and turning them into gore metal, death metal, making something more extreme. Then in the 1990s, you have black metal, where the first wave just pretended to be Satanic, then the second wave really was.”

As extreme as some of those movements were, Spracklen says they’re both different sides of the same coin: “All of it is about heavy metal proving that it’s counter-cultural, against the mainstream, angry at alienation. It's a space for rebels of all kinds.”

Scream Bloody Gore

There’s no doubt that metal fans, regardless of where our personal bad-taste lines lie, stand together in a shadow of strangeness. If the horror of metal is a way of distancing ourselves from certain people in our lives, could it also be a way of bonding us with others who share our passion for the loud and monstrous?

For a subculture inspired by the post-war horror boom, it makes perfect sense. We love to be scared, and there’s a certain power in sharing freaky things that will either disgust or delight our friends and family. From there, we can form our own band of weirdoes who share the thrill and revel in our commonality.

“We’ve evolved out of long nights where we got scared when we heard something in the dark that we didn’t understand,” says Spracklen, “we’re hardwired to react to things that make us frightened or uncomfortable. But some of us also get a visceral thrill from it. If you think about all the crime and fantasy shows on Netflix, for some people it’s a buzz, for some people it’s too much. If you enjoy it, you get to ride along with other fans and share getting excited about it.”

Maybe that’s why heavy metal subculture has survived the last 50-odd years with its iconography and popularity intact. The community aspect is alive and well, still giving sanctuary to those who don’t fit in – providing they’re happy to go along with the tropes. “You can absolutely be an individual” Spracklen jokes with some affection, “if your individuality is wearing a different logo on a different black t-shirt.”

So, are there any covers that give Professor Spracklen the creeps? “Maybe some of the Carcass albums. I don’t like looking at bits of dead things! It put me off for years. It was only when I got back into heavy metal in the early 2000s that I went back to find those records again and listen to them. And even now I probably wouldn’t study the covers or the inlays.”

There you have it. Even heavy metal professors get grossed out sometimes. Now, anyone for a spot of Cattle Decapitation?