You’re standing in a pitch-black hallway. The only thing you can see is writing projected onto a wall in the distance. You have no choice but to walk towards it – while praying you don’t stumble over something invisible to you. The words say: ‘The musical composition lasts 56 minutes and is played on a loop.’ That’s because, as you step through the doorway to your left, into a 8m-high room lit only by the spotlights illuminating 14 paintings by Edvard Munch, you’re listening to the new Satyricon album.

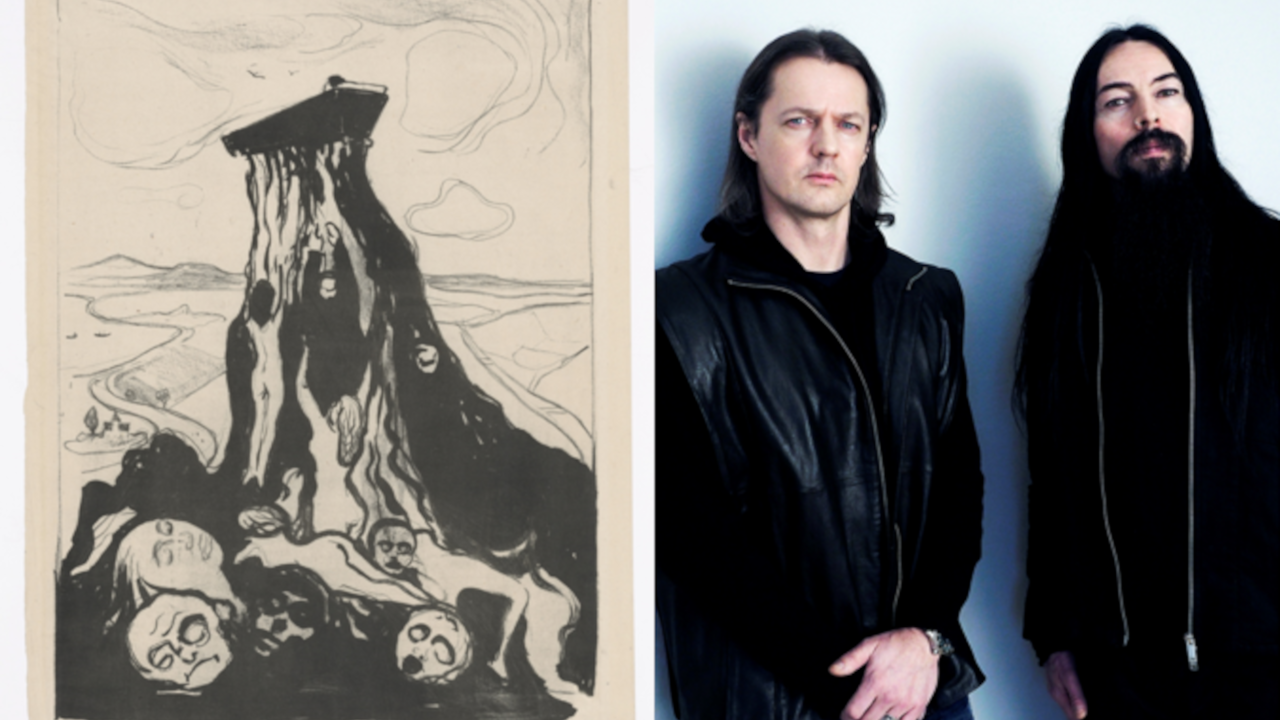

We’re at Oslo’s Munch Museum, at the press opening of their new Satyricon & Munch exhibition – a project dreamt up by the band, who wanted to write a soundtrack to their countryman’s disturbing yet beautiful art. Comprising one instrumental song, the album, Satyricon & Munch, is an awe-inspiring left turn.

As Satyricon’s frontman and songwriter Sigurd ‘Satyr’ Wongraven puts it during a Q&A session before we go inside, everything that’s usually at the forefront of their music has been de-emphasised, whereas everything normally in the background has been shoved forward.

While their last run of albums – 2008’s The Age Of Nero, 2013’s Satyricon and 2017’s Deep Calleth Upon Deep – flaunted grooving percussion, melodic riffs and glassgargling growls, this is all droning synths and ominous strings. Bar one movement of climactic tremolo picking, it’s black metal in spirit, but not in form. For Satyr, it’s been a welcome opportunity to broaden Satyricon’s horizons.

“We can’t subscribe to some teenager in Germany’s idea of the purity of black metal,” he says, when we sit down with him the next day. We’re in a cafe on the ground floor of the Munch Museum, 10 storeys below his exhibition. “I refuse to relate to people like that – people who weren’t even born when we were moulding the whole thing. They know nothing about it.”

Some define ‘true’ black metal using a checklist of traits – screaming, Satanic lyrics, blastbeats – but Satyr has another idea of what the genre should be: limitless. He was there at the beginning, when Mayhem co-founder Øystein ‘Euronymous’ Aarseth and his ‘inner circle’ were devising its purpose, pushing music and society’s limits with their sinister soundscapes and church burnings.

Black metal is meant to be transgressive, Satyr believes, and the bands that stop pushing at its constraints misunderstand it. It’s the same school of thought that’s made mavericks of Ihsahn and Enslaved. “I had my ups and downs with Euronymous, but he was a true philosopher,” Satyr remembers.

“I spent so many nights, so many hours, talking with him about black metal. His thinking was a huge influence on all of us.” He laughs: “This was in 1992, so for someone born in 2002 to tell me I’m not doing it properly? Oh, thank you!”

If black metal is meant to be an art form that challenges the masses and decimates convention, then Edvard Munch could be thought of as a precursor. He was born in 1863 in a farmhouse in the village of Ådalsbruk, 80 miles north of Oslo, and lost his mother to tuberculosis when he was five. Nine years later, one of his sisters died. Another was institutionalised for most of her life, and his brother was killed by pneumonia at 30.

He was frequently off sick from school, so his father read him ghost stories and Edgar Allen Poe poems. Munch’s most famous quote is, “I do not paint what I see, but what I saw”; as a result, his works were dark and nihilistic. Instead of using firm lines, he preferred to crossfade colours to create nightmarish dreamscapes. In 1892, an exhibition Munch hosted in Berlin shocked the conservative German public so much that it had to be closed. Fortunately though, this is not 1892 Berlin. Edvard Munch is Norway’s national treasure: as Satyr puts it, he’s “the cultural monarch of this country”.

Yesterday evening after the press opening, there was a la-di-da dinner at the museum, followed by speeches from Satyr and Munch Museum director Stein Olav Henrichsen – oh, and the actual King of Norway was in attendance. Such is the power here of Edvard Munch.

“He is one of the most acknowledged artists in modern art history,” Satyr explains. “I don’t think his work requires any assistance. If we add a bunch of stuff to the experience [of looking at Munch’s art], then I think we’re setting up obstacles. I want the room, music and artwork to create an environment where you can feel what he left behind more strongly than you would have if you didn’t have the music.”

Munch has been a part of Satyr’s life for as long as he can remember. In Norway, the artist’s paintings are shown to children when they’re in preschool. The connection between artist and musician grew stronger in 2017, when Satyricon used his lithograph Todeskuss (The Kiss Of Death) on the cover of their ninth studio album, Deep Calleth Upon Deep. Securing permission to use the piece marked the start of the band’s relationship with the Munch Museum, but it was a difficult process.

“They were all about procedure,” he says. “I had to go through all the stages of evaluation. I had a certain understanding of that, having worked with the opera.”

Barely 100m away, also on the bank of the Oslofjord, is the Oslo Opera House. There, in 2013, Satyricon performed their stomping black metal songs backed by the 55-piece Norwegian National Opera Chorus, captured for the album Live At The Opera. From the outside, it looks as though Satyricon have surprisingly been embraced by Norway’s cultural elite. Try to imagine Akercocke working with the Tate Modern, or Anaal Nathrakh collaborating with the The Royal Ballet. You can’t!

However, Satyr admits that heavy metal is still looked down upon by many tastemakers in Norway. Hammer asks if the Munch Museum was like that. His only response is a wink. To what extent has Norwegian black metal’s history of church-burnings and murder shaped people’s perception of them?

“Church-burnings and murder, they’re a part of our history,” Satyr says. “If that’s an obstacle that people have to overcome, then I can’t work with them. I’m not gonna distance myself from the scene I grew up in. I’m not gonna apologise and, a lot of the people who personally have something to answer for, they’re my friends. They did what they did, they were prosecuted, they served their time and they were released. That’s how society works.”

With Satyricon in the Munch Museum’s good books, Satyr thought up the idea for the exhibition in early 2018. He was walking in a forest far south of Oslo, decompressing between live shows, and doing something he doesn’t normally do when immersed in nature like that: listening to music.

“It’s interesting; I became more aware of certain smells,” he remembers. “Everything became so amplified. And then, even more intriguing to me, I just thought: ‘What if I did something with Munch?’ I wasn’t thinking about art; I was thinking about Munch, specifically.”

When the pandemic halted live music in the spring of 2020, composing for Satyricon & Munch became Satyr’s top priority – even if it took him a while to get started.

“The first six to nine months of Covid made me feel like I was in a cage,” he recalls. “I learned that what makes my day is the freedom to express myself. When limitations are imposed on me, I feel restless; I feel like a shallow, meaningless version of myself.”

The turning point was when he bought himself a new toy: a Moog analogue synthesiser. The idea of mastering the instrument motivated him, and he ended up using it for Satyricon & Munch. Even though pandemic restrictions have eased and live music has come back, the band haven’t got any shows planned.

“The pandemic has crushed the Satyricon machine,” Satyr admits. “I don’t think we’re going to be able to do what we want to do this year. We just don’t have the crew and the live band to make it good.”

He has no idea what the future of Satyricon will be sonically, either. Will they revert to black’n’roll, maintain the fearlessness of Satyricon & Munch, or find some middle ground?

“From Satyricon, you expect the unexpected,” is all Satyr can say, genuinely unsure of his own trajectory. He knows he would like to take the Satyricon & Munch experience on tour at some point, though. But even then, the logistics of making it happen are a mystery to him.

“It’s too early [to talk about what’s next],” he states. “This has been such an overwhelming task that I haven’t even been able to think about it. But, everything I’ve learned from this project will be reflected in the future.”

One hour and two pints deep into the conversation, Satyr has to disappear into Oslo’s urban sprawl. Tomorrow, Satyricon & Munch will open to the public, and show them what we already know: that Edvard Munch was black metal as fuck.

Satyricon & Munch is available now via Napalm. The exhibition runs until August 28. See www.munchmuseet.no/en for details.