In the winter of 1985, Scott Gorham was attempting to rid himself of an addiction to heroin. So tenacious was this monkey that had made its home upon his back that the 35-year-old American guitarist had installed a resident nurse in his four-bedroom home in south-west London. Alongside matters of medication, it was the nurse’s job to ensure his patient’s sense of resolve remained intact, and that his gaze did not return to the dark habits that had led him here in the first place.

By this stage Gorham, who had helped call time on the career of his former band Thin Lizzy two years before, had turned his back not just on music but also on the people with whom he had previously shared his world. “That’s what you have to do to get better,” he explains. “I wouldn’t go to clubs, for fear that someone would offer me a taste and suddenly I’d find myself in the bathroom snorting up some shit.”

Invitations to see friends in touring bands appearing in London would be declined. The guitarist suspects that these people probably thought he was too big for his boots, but that wasn’t the case. What it was, in fact, was that Gorham was junk-sick and tired of the drug scene. Yet despite the repulsion, he was unable to free himself from his habits. A pivotal question had begun to tug at his sleeve: ‘Am I going to be taking this shit for the rest of my life?’

The answer, he decided, was no. And so it was that on a frigid winter’s day, Gorham’s nurse-cum-emotional-bodyguard suggested that patient and protector play a round of golf. Whatever misgivings the guitarist may have had, the truth was that he had nothing to do that day but grimace. Sure, he answered, why not?

“I could only play nine holes, but it helped take my mind off the drugs,” he says. “I was wearing about nine sweatshirts, and while the game didn’t completely take my mind off the pain it did give me something else to think about – hitting a little white ball into a hole. The next day the nurse said to me: ‘Well, what do you want to do today?’ And I said: ‘How about we play golf again?’ He probably looked at the weather and thought: ‘Really?’”

Today, on a beautiful early spring day that feels like the full flush of summer, Gorham may well be telling a story of how one addiction replaced another. Thirty years on, he is still beholden to a pastime that Mark Twain once described as constituting “a good walk, ruined”.

These days Gorham tees off at Richmond Golf Club in suburban south London, on to fairways so resplendent with richness it appears that the colour is on the fritz. With his time increasingly dedicated to life on the road, Gorham explains that in order not to pay “what would work out at around three-hundred-and-fifty pounds for a round of golf” he has rescinded his full membership in favour of a stipend designed for players who work in the performing arts, which equates to just £16 per round. Tellingly, Sean Connery was once the president of this branch of the club’s clientele.

Unannounced visitors are greeted with polite suspicion. Hats, it is explained at the bar, may not be worn indoors for reasons of “etiquette”. To the left hangs a framed picture of the Queen that is as dated and drab as 1970s England. A poster for the Basil Brush Show is the only advertisement pinned to the noticeboard. Despite the fact that Alice Cooper, Iggy Pop and the Beastie Boys long ago helped dispel golf’s stuffy image, here the atmosphere is one of matey but cloistered civility.

Everyone knows who Scott Gorham is. “Oh, hi. I’m just doing an interview,” he explains to a late-middle-aged man who approaches the table at which he is sitting. The man tells him that this morning on Absolute Radio he heard mention of Gorham’s band, Black Star Riders. Was it anything to do with his group’s opening slot on this winter’s Def Leppard tour, the guitarist wonders? Yes, yes, that was it. Gorham says that he’s thinking of asking for tickets for any member of the club who would like to attend the London show. Good idea, comes the reply, along with the suggestion that a coach could be hired to ferry the guests to the O2 Arena. An idea that sounds no more likely than Richmond Golf Club pinning up election posters for the Socialist Workers Party’s annual get-together.

Gorham pulls on an electronic cigarette. As his conversation with the man peters out, his eyes dart reflexively towards other people in the room, people who know who he is but not, perhaps, what he once was. He motions towards a white double door.

“Let’s go in there,” he says, “it’ll be quieter…”

The first time he met Phil Lynott, in 1974, Scott Gorham was 23 and desperate. A resident of London for five months, the California-born guitarist had just 30 days before his visitor’s visa expired, rendering his status as that of illegal alien. “I didn’t want to return to Los Angeles with my tail between my legs,” he explains, “but it looked as if that was exactly what was going to happen. By that point I was ready to jump on anything. I would have gone anywhere and done anything.”

A friend told him of an Irish rock band who were auditioning new guitarists. Despite the fact that Gorham believed Thin Lizzy to be the worst name for a band that he’d ever heard, he asked that his name be mentioned. Taking a call on a public phone on the landing of the Fulham flat he shared with his sister and brother-in-law Bob Siebenberg (then, as now, the drummer for Supertramp), he was invited to meet Lynott, along with Lizzy’s drummer Brian Downey and guitarist Brian Robertson, at an African dinner and dance club in West Hampstead.

Gorham had no idea what Phil Lynott looked like, let alone that he was black; at first he assumed that the Irishman was one of the club’s waiters. In a back room the guitarist removed from its case “a Japanese Les Paul copy that was so awful, whoever made it was too embarrassed to even put their name on the head. Brian Robertson just looked at me, like, ‘Really?’” Gorham played so badly that he assumed that he would never see the three musicians again.

But if Gorham was surprised that Phil Lynott asked for his number, that was nothing compared to the shock of a phone call later that night inviting him to become a member of his group. Put on a wage of £30 a week, the guitarist celebrated his good fortune by moving into a one-room bedsit near Hampstead Heath. He slept on an army cot and surrendered coins of the realm to an electricity meter.

“At first I thought: ‘Okay, Irish, rock music, black guy… It just didn’t compute with me at all,” he says of the night that would change his life. “But Phil was just so enthusiastic and energetic. There was just something about he and I, we just clicked right off the bat.”

At this time, Gorham did not think of himself as a professional musician, let alone an apprentice rock star. It was by both accident and design that he’d left his home country with his bad reputation intact. At high school he was just one of three people who smoked marijuana, and he did it blatantly. What might have been little more than workaday rebellion was recast as something far more serious following an arrest in Arizona after Gorham offered to sell weed to an undercover cop.

Adamant that the only reason this exchange was proposed was so that he could buy the petrol needed to drive his friends home, nonetheless this one-time-only drug deal carried a prison sentence of between two and five years. With the help of an uncle who was a lawyer, Gorham escaped incarceration. His liberty intact, the most significant decision of his young life was to escape America itself.

He arrived in London to a torrential downpour and more red-brick buildings than he had ever seen in his life. Somehow even this seemed exotic, not least because London was the city in which the world’s best music was made, a metropolis where rock stars are there to be tripped over on every single street. And while in 1974 this was hardly likely to be the case, over the course of a two-hour audition in West Hampstead his fortunes were suddenly married to those of a man who may as well have come from a different planet.

“Phil just had a gift,” Gorham says. “He had a gift for music and melodies, and he had the gift of writing songs that sounded wise, that sounded as if they were being sung by a man. No matter what kind of song he was singing, it sounded like the truth.”

Just weeks after being hand-picked from obscurity, Gorham’s life went from pick-up jamborees in London pubs in the name of his ad-hoc group Fast Buck, to employment in a group the status of which ran to appearances on national television. Phil Lynott was a natural-born star – Bob Geldof once observed that he saw it as his day began with a fresh pair of leather trousers and a limo to Tesco – but Thin Lizzy’s leader understood the line which separated friendliness from foolishness.

This Gorham recalls from a spirited altercation between Lynott and drummer Brian Downey in a television studio prior to the American’s first on-screen appearance with his new colleagues. Prior to the booking, Thin Lizzy had treated themselves to a short period of rest, during which the drummer had decided to grow a beard. This Laurel Canyon look ran contrary to the band’s cool swagger, so much so that Lynott gave his drummer two options: shave, or forego the television appearance.

“I remember watching this happening, this really angry row, and thinking: ‘Really, we’re going to break up over fucking facial hair?’” Gorham says. “But Phil was like that. He was a good guy, but he never lost sight of what it was that he wanted Thin Lizzy to be. That was what was always most important to him.”

Listening to Gorham’s words today, the character sketch of Phil Lynott is one of band leader and, even, visionary, but not of dictator, benevolent or otherwise. From the start, Lynott was keen that his bandmates contribute material in order that everyone might share in publishing royalties. An absence of professional enmity and an abundance of personal warmth that was extended to Gorham on the pair’s very first meeting meant that they were bound together by more than music.

“He was my friend,” says Gorham. “I was no one when I joined that band; I was just three weeks from being kicked out of the country. And here I was in a real band, with this guy who is clearly a star. But he was generous, too, and he brought the best out of people. I mean, I have a songwriting credit on the first song from the first album I recorded with the band [She Knows, on 1974’s Nightlife], all of which came about because Phil heard me jamming this riff and encouraged me to expand on it and use it in the song.”

When success came calling, it came fast. Thin Lizzy were on tour in the United States in 1976 when word reached them that The Boys Are Back In Town was a hit single. Its parent LP, Jailbreak – Gorham’s third album with the band and “a record that we just threw out because the first two were such failures” – found itself similarly airborne. The band reacted to fame like cats to catnip. On stage they were the first to build what are now known as ‘ego ramps’, first one and then three in order that their front line could have one each. Ask Gorham today if he enjoyed the fruits of Thin Lizzy’s labours and he will look at his questioner as if he were a perfect idiot: “Absolutely! What, are you kidding me?”

In fact he enjoyed these fruits so much that they could not, and did not, last. Just five years after The Boys Are Back In Town had established itself as one of the most iconic hard-rock singles of the 1970s, Gorham was urging Lynott to shift their union from the present to the past tense.

“I went to Phil one time and I was in pain,” he recalls, “I was just so tired physically and mentally. And I said: ‘Phil, I’ve had it, man. I’m going to have to walk… All we’re really doing is dragging the name down into the shit.’”

That day the frontman convinced his guitarist that splitting up the group was what they would do, but only after one more album and a final world tour. “I remember leaving his house that day thinking: ‘Okay, I came here intending that we split up the band, and I’m leaving having agreed to another album and a world tour,’” he recalls.

At this stage things were becoming wretched. In Japan, at a show at Tokyo’s Budokan Hall, Lynott and Gorham were so junk-sick that even today the latter can’t believe that they made it through the gig. During the anyway mournful Still In Love With You, the pair locked eyes with gravid gazes of mutual misery. According to Gorham, the rivulets of sweat streaking down his bandmate’s face made it look like he was crying.

“You get to the point where you don’t feel like playing,” he says. “My whole life I wanted to be on the fucking stage. My whole life was geared to doing this; I’m living my dream. But now you’re sitting on the side of the stage and you haven’t had enough drugs and suddenly you’re thinking: ‘I don’t want to get up there and play. I’m not stoned enough, I don’t want to do this.’ And when you realise you’re saying this, then something’s really wrong, the whole thing has gone to shit.”

Heroin took hold of Thin Lizzy in 1979, when they were in Paris recording the Black Rose album. They were visited in the studio by a party of characters of Phil Lynott’s vague acquaintance, one of whom introduced Gorham to this hardest of drugs. The honeymoon period with heroin was nightmarishly short, just six months; this was all the time it took for the guitarist to acquire a habit that required constant maintenance.

Gorham holds heroin responsible for the demise of Thin Lizzy, a denouement that, more than 30 years later, he still describes in language of tragedy and regret. “If I had my time all over again I would never take heroin,” he says. “Never. It does nothing but harm. The costs are so high.”

Why did you take it in the first place?

“It was the usual clichéd crap,” he says. “There are often a number of different reasons why musicians take that drug. Sometimes it’s because of stage fright, even, which certainly was never a problem to me. But it was just something to do to break up the monotony of being on the road. You have a lot of time on your hands, so you’ve got to do something. And I did that. You know, I’m on tour and I have a couple of days off, so… let’s get high! But very quickly it takes its toll; it doesn’t take long before everything turns to shit. I got clean in the end, but some of my best friends are dead because of heroin.”

The last time Gorham saw Phil Lynott – an occasion he still recalls “vividly” – was only three weeks before the frontman’s death in January 1986. On account of the guitarist then being in the early stages of recovery, the two of them hadn’t met for almost a year. But recently the guitarist had been in Los Angeles recording new material, and even though he thought that stepping into Lynott’s orbit might well be “dangerous”, nonetheless he keenly wanted him to hear these new songs, and to solicit his opinion.

“This was at his house in Kew,” Gorham explains. “I arrived at eleven o’clock in the morning, and Phil answered the door dressed in a bath robe, PJs and slippers. He was all puffed up. Because of his asthma he could hardly breathe. See, that’s what happened; every time he took smack the asthma would come back at him with a vengeance.”

Here Scott Gorham sinks into disturbing mime of a man gasping for breath. He remembers the phone ringing, and of Lynott responding to the caller’s message with the words: “Fucking great, that’s fucking great”. The phrase is recounted in an uncannily impeccable Celtic baritone. Lynott had just learned that a possible drug possession charge against him had been dropped. He celebrated by filling a pint glass three-quarters full with raw vodka and then sinking the drink in one. Two large mouthfuls were duly removed in a second helping.

Phil Lynott then suggested that he, Gorham and Downey should get Thin Lizzy back together.

“I’m looking at him thinking: ‘Are you kidding me?’” he says. “I’m there thinking: ‘You know what it takes to be out on the road, man. You’re never gonna make it out there in your condition.’ And he must have seen the look that I gave him, because then he said: ‘Oh, man, don’t worry. I’m gonna get my shit together; I’m gonna get off of this crap, man.’ And he sounded so determined that I actually believed that he was going to do it.”

Do you believe that Thin Lizzy could have reunited had Phil Lynott gotten his “shit together”?

“Yeah, I do.”

Do you think the band would have reunited?

“Oh yeah.”

But?

“But the problem was that he had done way too much damage to his body by that point. If he had stopped that second he was still going to die on the appointed day.”

On January 4, 1986 Gorham was in his basement when his wife Christine took the phone call that brought the news that Phil Lynott had died. Hearing the sound of her tears, the guitarist just knew. He remembers thinking: “That’s it, he’s dead.”

“I was grief-stricken,” he says. “And I was surprised too. He’d been through hairy-ass bouts of hepatitis, and all sorts of crazy health issues, and he’d always come through this with flying colours, as if nothing had ever happened… You know, this is Phil Lynott we’re talking about, the iron man. This man in indestructible. So when we got the news that he’d died I was dumbstruck.”

As much as anything, though, this is a story of Scott Gorham escaping not from Phil Lynott’s shadow but from their shared memories. For although the American visited the Irishman’s grave in Dublin just once – an occasion he says is too depressing to repeat, due to the fact that for him Lynott is not “down there, but up here” – the resurrection of the Thin Lizzy name in 1996 offered shelter in the form of magnificent music and meaningless nostalgia.

Ironically, the idea of resurrecting the Thin Lizzy name came not from Gorham, but from guitarist John Sykes. Despite him being a member of the group for just one album, 1982’s Thunder & Lightning, Sykes’s decision to perform a number of the band’s songs on a solo tour of Japan would prove pivotal. Struck by the ovation that greeted these songs, he persuaded Gorham to put his name to what would be one of the most unlikely reunions in the history of rock.

“Originally the idea was just to do one tour of Japan,” Gorham explains. “At the time, it seemed to me that people were forgetting about Thin Lizzy. The music that we had made was fading away, as well as the memory of Phil Lynott. But we did those shows and they went great, and suddenly we have people from all over the world wanting us to come and play for them.”

Given that the impetus for Lizzy’s resurrection was John Sykes’s, did he once again feel like the first lieutenant rather than the man in charge?

“No,” Gorham says. “There was never any question that I was the one in charge. It couldn’t have happened without me. I’m the one who has a responsibility to the Thin Lizzy estate, as a company, so I had to be a part of it.”

Yet despite a level of genuine acclaim for the re-imagined Thin Lizzy, and despite having played on the original versions of the songs the band were now schlepping around the world – indeed, having co-written a number of them – still a clawing sense of inauthenticity could not be prevented from leaking through the cracks.

“That was the weird thing,” Gorham says. “I felt that I was in a cover band covering my own songs. And I just couldn’t get it out of my head that this is what was happening. Even though we were drawing really good crowds with sold-out audiences and all of that, the thing at the back of my mind was that this is still a fucking cover band. No matter how good it is, that’s what it is.”

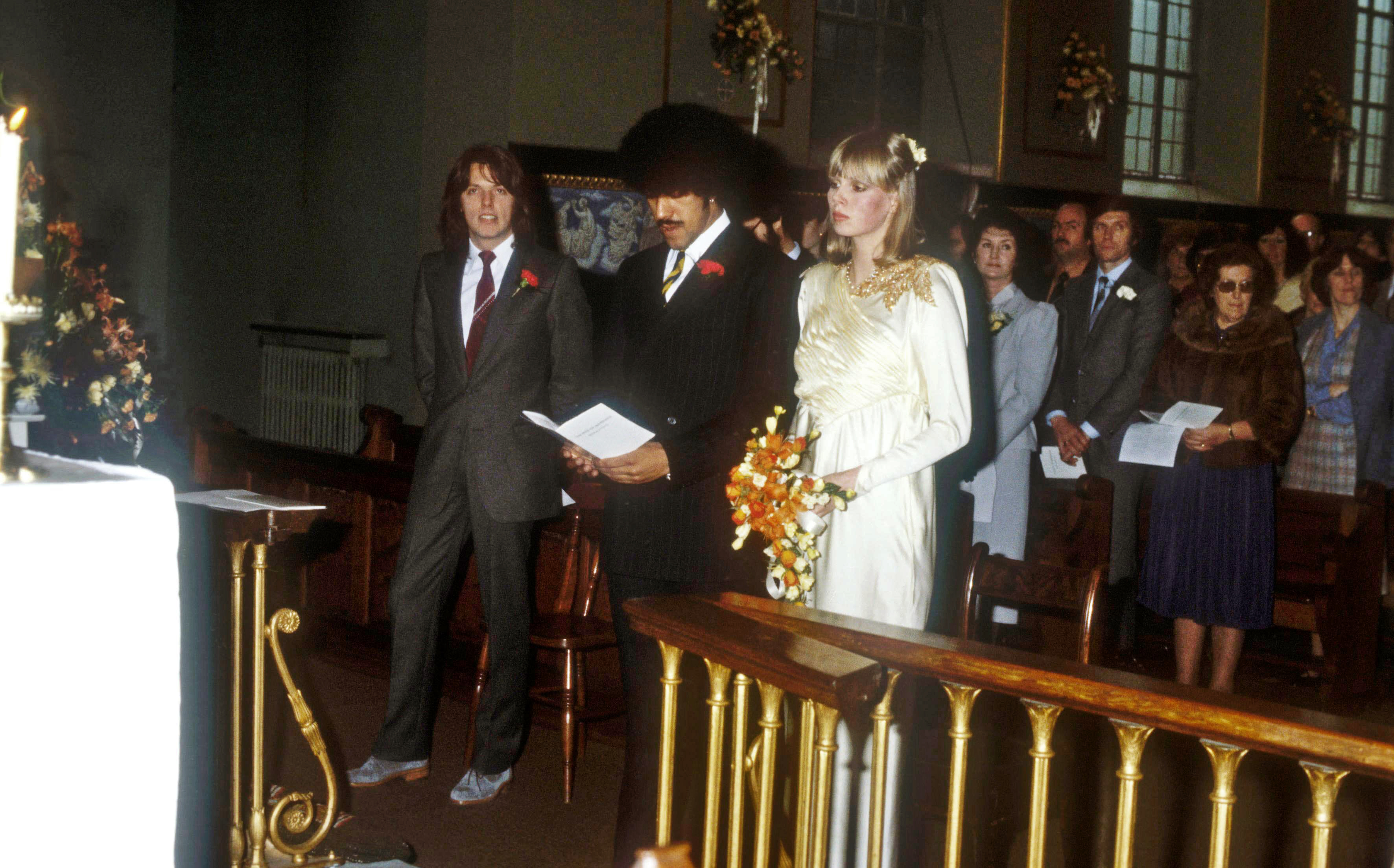

Gorham’s decision to transfer Thin Lizzy’s latter-day stock to the new company of Black Star Riders (above) was not without a measure of pragmatism. For one thing, the Lynott estate was not thrilled by the idea of the group recording new material under a name so intimately associated with its late band leader. For another, Gorham says he was wary that such a move would “alienate fifty per cent of the audience, who would be furious that we’d dared to do such a thing”. And anyway, the guitarist himself was also queasy about the idea. For years he’d been lying to journalists and even to other members of the group regarding his future intentions for the project, claiming that a new studio album hovered somewhere near the horizon. But in his quietest moments he knew that he was unhappy with even the thought of this. “I really didn’t want to do it under the Thin Lizzy name, because Phil wasn’t going to be there,” he says. “It just seemed wrong.”

At a time of life that other men might view as ripe to utilise the full benefits of their expensive golf club membership, Gorham effectively started again from scratch. And while his claims that among Black Star Riders’ audience there are people who are unaware of an association with Thin Lizzy suggests that said people have recently emerged from a coma, the fact that the group’s second album, The Killer Instinct, entered the UK album chart in the Top 20 – and would have been placed much higher had it not been released in the same week that the Brit Awards took place – is something that can’t be dismissed lightly. At a time when bands increasingly resemble brands, the guitarist’s decision to propel himself forward carries with it a measure of honour. As he is not at all slow to admit, the enterprise could well have been a disaster; a creation not even worthy of contempt, merely a thing “that everyone ignored”.

“It’s a really great feeling that, forty years after first coming to London, I’m here making music,” he says. “If you’d have told me in 1978 that I’d still be doing interviews in 2015 I’d have thought you were fucking crazy. If I’d have thought about it at all, I would have thought I’d probably be dead by now.”

Thinking about this now, Scott Gorham allows himself a smile that lies halfway between the ease of California and irony of England.

“But obviously I’m not.”

“I THOUGHT THE BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN WASN’T A SINGLE!”

Scott Gorham on how Thin Lizzy’s breakthrough 1976 hit very nearly didn’t happen.

In early 1976, Thin Lizzy were just another rock band from this side of the Atlantic trying to break America. They had just released their Jailbreak album when the big break they were waiting for finally came through.

“I remember we were playing in some club somewhere in the US when our manager came in and said, ‘Well, looks like we’ve got a hit’,” says Scott Gorham. “We were, like, ‘A hit, really? With which song?’ Seriously, we didn’t have any idea at all which song it was that had taken off for us.”

Ironically, the song which made Thin Lizzy famous wasn’t just a surprise hit single – the original plan was that it wasn’t going to be on the album at all. “Actually, to tell you the truth, we weren’t initially going to put The Boys Are Back In Town on the Jailbreak album at all. See, back then you picked 10 songs and went with those, because you couldn’t put any more on an album because of the time restrictions of vinyl. So we recorded 15 songs and of the 10 we picked, that wasn’t one of them. But then the management heard it and said, ‘No, there’s something really good about this song.’ Although back then, it didn’t yet have the twin guitar parts on it.”

For Gorham, the song’s success was a lesson that the smallest decision can mean a band taking an entirely different path – one that might not be entirely beneficial to their career. “Obviously The Boys Are Back In Town is the one song that really changed things for us, and I’m very thankful that it did. But I also think about how thin the line can be that separates success from failure. Whenever we’re discussing lead-off tracks with Black Star Riders, I always say, ‘Don’t listen to me, I’m the one who thought The Boys Are Back In Town shouldn’t have been a single!’”