Sebastian Bach’s enthusiasm for life in general and music in particular is permanently off the scale. Within the first 10 minutes of our conversation today he has already excitedly namechecked Kiss, Van Halen, Twisted Sister, Rush, Queensrÿche and, most surprisingly, 80s UK glam tarts Wrathchild.

“I fucking loved that band,” he says of the latter, then launches into their song Trash Queen. “‘Trash queen, trash queen… she’ll suck you clean!’ Man, I have that album on red vinyl.”

Right now, though, he’s most excited by his own music. And rightly so. His new solo album, Child Within The Man, is his first in a decade, and only his third studio album since he was fired from his former band, New Jersey hellions Skid Row, in 1996. It’s a terrific record, a souped-up version of the kind of hard rock with which he originally made his name, with Bach’s powerhouse voice and megawatt charisma the neutron star powering it.

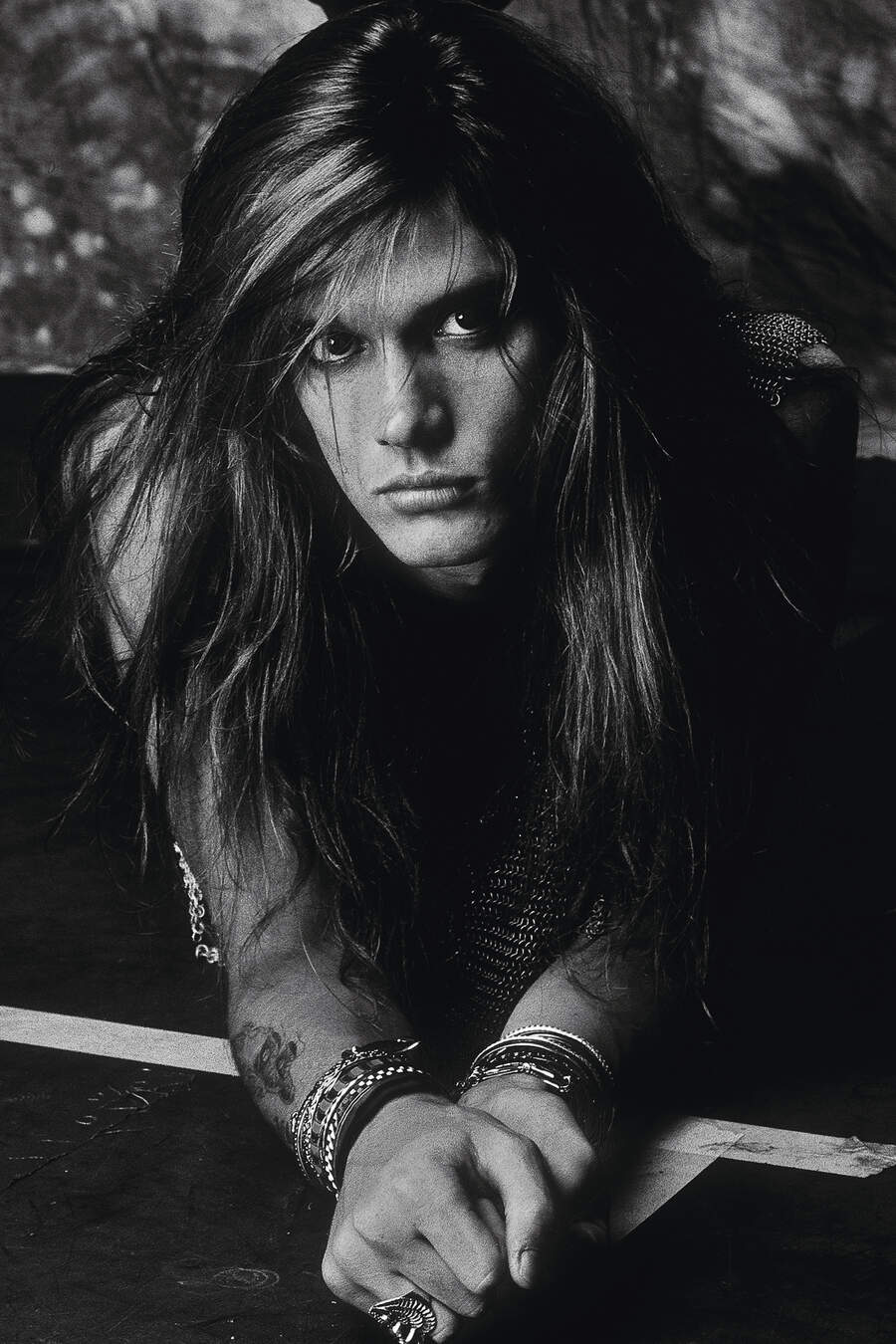

But then he was always one of rock’n’roll’s great frontman: six-feet-three of poster-boy good lucks and unfiltered attitude. The son of the late artist David Bierk, whose work adorned the sleeves of Skid Row’s Slave To The Grind and Subhuman Race albums, as well as every Bach solo album up to and including Child Within The Man, he was born in the Bahamas and raised the town of Peterborough, Canada. He may have been educated at the private Lakefield College (other notable alumni: Prince Andrew, and Arrested Development star Will Arnett), but rock’n’roll got its claws in him early – he was playing clubs with his first band, Kid Wikkid, at the age of 14.

It was as frontman with Skid Row that he made his name. With Jon Bon Jovi and his management company in their corner, their vertiginous rise saw Bach become one of rock’s most recognisable faces when he was barely out of his teens. Their first two albums, 1989’s self-titled debut and 1991’s Slave To The Grind, were huge hits – the latter even reached No.1 in the US. But it was always a fractious union between the punk kid from Canada and his New Jersey bandmates, and Bach was fired from Skid Row in 1996. When they returned a few years later, it was without him.

His own path has been marked by some dizzying highs and soul-scraping lows. He’s done TV, films and, famously, a stint on Broadway, and he counts the likes of Rob Halford and Axl Rose as friends. But then there were the lean post-Skid Row years, which found him struggling to recapture past glories. He had the traumatic experience of having his house destroyed by Hurricane Irene in 2011, losing many possessions in the process.

“I’ve had a pretty fucking extraordinary life,” he says. And he’s not joking.

Who was the first musician that made you think: “I could do that”?

The first musician I became really obsessed with was Elton John. Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting was one of the heaviest songs I’d heard when I was a little boy - it was heavy metal to me. But I never thought I could be Elton John, or Kiss or Cheap Trick or Rush. But I saw Mötley Crüe on the Theater Of Pain tour in Ottawa. For the first time ever, I was staring at the stage thinking: “Why am I in the audience?” It was the most powerful feeling I had ever felt: “Hey, idiot, go fucking do your own band.” It was almost like I couldn’t wait to get out of there. It was the weirdest feeling.

You were already in a band, Kid Wikkid by then. You’d joined them when you were fifteen. That must have been a crash course in rock’n’roll.

I might have even been fourteen. I used to tease my hair up like [Wrathchild frontman] Rocky Shades. I was six-foot-three when I was fourteen, and my hair was another foot and a half. I wore the tallest boots that I could find, and I was about a hundred and seventy pounds. I wore so much make-up that no club owner ever questioned my age. Nobody ever said: “Are you old enough?”

Were your parents supportive?

My dad was supportive, but he had terms. He wanted me to finish school. He said: “I will pay for vocal lessons in Toronto, under the condition that if you ever miss one I will stop paying for them.” He was not supportive of me moving from Peterborough to Toronto and playing in clubs at the age of fourteen or fifteen.

What were you like back then? If I’d met you at that time, what would I have thought of you?

I liked to party. I loved drinking beer. I drank fucking tons of beer when I was I kid. I used to go to gigs all the time. That’s the kind of guy you would meet - a very enthusiastic fan and collector of rock music. I haven’t changed at all.

After Kid Wikkid, you had a brief stint in Madam X, who had already released an album. Did you think: “This is it, I’ve hit the big time”?

Well, I did think that. It didn’t quite turn out that way. All I can say about Madam X is that the focus was one hundred percent on the look of the band. We spent all our time in the bass player’s backyard, making a paper maché head that would go behind the drums and open its mouth. When I joined Skid Row, the whole focus of that band was about the songs.

You came to Jon Bon Jovi’s attention after singing at noted rock photographer Mark Weiss’s wedding. How did that happen?

Someone came up to me and said: “Sebastian, Jon Bon Jovi’s parents want you to join them at their table.” So I sat next to Jon’s dad and we had a great time together. Skid Row were looking for a singer at that point, and I think they were partly responsible for suggesting me for it. There was also a guy named Dave Feld, who orchestrated the sending of a cassette from Dave Sabo [guitarist] and Rachel Bolan [bassist] to me in Toronto. It had about six songs on it, and three of them ended up on the first Skid Row album.

What did you think of the tape?

I wasn’t blown away by it, cos the singer [original Skid Row vocalist Matt Fallon] sounded just like Jon Bon Jovi, and I wanted to be more metal than that. But the more I listened to 18 And Life and Youth Gone Wild, the more I knew that these songs were meant for me to sing. Little did I know that we’d actually be bigger than Wrathchild [laughs].

What did you make of the Skid Row guys the first time you met them?

I was really impressed that they’d paid for my plane ticket from Toronto to New Jersey – a hundred and forty-nine dollars. I thought I’d hit the big time. Eight months later, I looked at my accounting and I got charged back for that plane ticket. That’s rock’n’roll. Rachel picked me up from the airport, and we went to Snake’s house. The whole band was there, and we immediately started drinking beer.

So then the guys take me to a bar called Mingles down the street. There was a band playing, so we jumped on the stage and started jamming a little bit. There were Budweisers involved. Snake has a recollection that I got in a fight in the club. I don’t remember that, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen [laughs].

Skid Row became very famous very fast. Did that scramble your brain?

I didn’t have any time to think about how I was going to handle it. A typical day in the life of Skid Row on the road opening for Bon Jovi in 1989 would be doing interviews from noon until about six, then going on stage at seven and wondering why my voice was shot. It was cos I’d be talking all day, but I didn’t realise that at the time. Then we would get on the bus, crack open a couple of drinks, drive to the next town and repeat.

We did that for the Bon Jovi New Jersey tour and then the Mötley Crüe Dr. Feelgood European tour, then the Aerosmith Pump tour, then the Guns N’ Roses Use Your Illusion tour, then our own tour with Pantera, Soundgarden and even Nine Inch Nails opening for us.

Was Skid Row a party on wheels?

Wherever we went there’d be an ice cooler full of beer for us. You’d get in a limo to go somewhere and there’d be a cooler of beer, or you’d get off a flight to Japan and there’d be a case of beer in the van to take you from the airport. Everywhere we went there was always a case of beer. We didn’t think it was bad. It was great.

Did it ever get out of control for you personally?

Yes. I would say to anybody that cocaine is over the edge. When you start doing that drug, you’re down the path of out of control. And I did like that stuff, especially around the Slave To The Grind tour. Everybody was doing it. That’s the way it was in the eighties. The first time I ever went to [fabled Hollywood hangout] The Rainbow, people would shake my hand, and when they shook my hand they would pass me a bindle of blow. I was like: “What is this? Is this for me?” And it was free! I can’t stand that stuff now. I haven’t touched that stuff in years. I’m not interested in the least.

You were a loose cannon back then. You got into a public spat with Jon Bon Jovi, which was ballsy. But do you wish you’d been a bit more measured back then, maybe bit your tongue a little?

Yes I do. At the bottom of that [Bon Jovi spat], we were not happy with the contract we signed for the first record. None of the band were. But looking back, we probably would have never made it without his help. It wouldn’t have been possible.

You were criticised for wearing a T-shirt saying ‘AIDS Kills Fags Dead’ in a photo in a magazine, and you were sued by a female fan who was hit in the face by a bottle you threw at a gig. What would you say now to that kid you were then?

Nothing. I’m not going to answer that question.

You wouldn’t give that kid any advice, knowing what you know now?

Next question.

Okay. You were close to the Guns N’ Roses guys around that time. How did you get to know them?

The first time I met Axl was the night we opened for Aerosmith at the Los Angeles Forum in 1989. Lonn Friend, who was the editor of RIP magazine, said: “Somebody’s here who wants to meet you,” and he brought Axl into my dressing room. We hit it off straight away. He’d been invited to sing Train Kept A’ Rollin’ with Aerosmith that night, and he wanted to know if I had it on tape so he could learn the lyrics. I did, so we played the song on this tape deck I had. We became really good friends. And I actually lived at Slash’s house for two weeks back in, like, 1990. I have no idea why. I guess we were just buddies. It was crazy.

Skid Row’s second album, Slave To The Grind, reached No.1 in the US. How did you celebrate?

That day we were opening for Guns N’ Roses in Largo, Maryland. It was just when they’d switched from the old way of accounting for sales to Soundscan, which scanned copies as they sold. You used to have to wait a couple of months to find out, but you could tell right away. And [famed Japanese journalist] Masa Ito from Burrn! magazine walked on to the bus going: “Bazu! Bazu!“ – cos they always add a ‘u’ to my name – “Your record, number one!” I just went: “What the fuck!” Guns N’ Roses were doing a soundcheck, so I ran up to Duff [McKagan] on stage and went: “Duff, Duff, our album came out!” And he went: “What number?” “Number one!” He just didn’t understand. It was a new way of doing it.

Was there a point when you sensed things were changing for Skid Row? That maybe the end of the band was approaching?

Not so much musically, more the interpersonal stuff. I had to have my own bus, I wasn’t allowed to be on their bus. After we played Donington [the 1992 Monsters Of Rock festival], Slayer invited me on their bus back to London, which is quite the drive. That was when I was really into the blow. On that trip I was doing mountains of coke, while Slayer were going: “This guy’s nuts.” When we got to the hotel, I was so fucked up that even Slayer wouldn’t hang out with me either.

What was the issue between you and the rest of Skid Row?

Nobody likes to hang out with somebody that’s doing cocaine. If I’m in the presence of somebody doing that now, I leave the fucking room. But that was me back then.

You left Skid Row in 1996, after the Subhuman Race album. Were you fired?

Yes. We were offered to open up for Kiss on their 1996 reunion show, at Meadowlands in New Jersey, our home. I’m a serious Kiss fan, I couldn’t even comprehend that we could open for them at a reunion show. At the time, Rachel had a side project called Prunella Scales that he formed with our road crew – guys that I had been paying weekly for years. I get the message that Skid Row can’t play with Kiss at Meadowlands because Prunella Scales are busy.

So I call Snake on the phone. He doesn’t pick up, the answering machine’s on, and I proceed to freak out: “How you could you do this to me? How could you do this to the band?” I used some rotten language, I was pissed off. Sorry, that’s what happens to human beings sometimes. As the story goes, Snake says he has a roomful of family and friends when the message was playing. And he calls me back and goes: “Nice message. You don’t have a guitar player any more.” That’s how I was informed. If he’s not my guitar player, I guess I’m out of the band.

How did you deal with being fired?

Well, I built the band with the best years of my life, and that’s no exaggeration. My mom and my aunt were visiting me from Canada. There was a bunch of snow, and I remember we were sitting there in the snow going: “How can you make it in rock’n’roll, which is a one-in-a-million thing, and then just throw it away. How is any fight more important than that?” That, to me, was just nuts. I always assumed – naively – that bands that had gold and platinum records would be like Rush, they would be together forever and ever, and release twenty-five albums. I never thought Skid Row would only release three albums.

After you left Skid Row you started a solo band. What was that like?

I started my solo band, I didn’t even know if I could do it. I was doing a lot of stupid shit back then. I would do tribute records for five hundred dollars. I was in Skid Row for so long I didn’t know how to be anything else. I shouldn’t have been doing all that, but at the time I didn’t know what else to do.

The first album you released after leaving Skid Row wasn’t a solo record, it was the debut album from The Last Hard Men, a bizarre supergroup featuring you plus members of The Breeders, The Smashing Pumpkins and The Frogs. What the hell was that all about?

That came with Kelley Deal from The Breeders. She just had this wacky idea to form a band with those people and she wanted me to sing. She called me and said: “You’re a punk!” I’m like: “What are you talking about? Do you have the right phone number?” You’d have to ask her, I don’t really get it either. It’s not my finest moment [laughs].

You released your debut solo album, Bring ’Em Bach Alive, in 1999, but then you pulled another left turn and signed up for the Broadway production of Jekyll & Hyde. How did that happen?

Frank Wildhorn, the guy who created the show and wrote the music, said: “I want a rock star to play Jekyll & Hyde on Broadway.” He came to Jason Flom, who had signed Skid Row to Atlantic, and Jason said: “Sebastian Bach.” Jason called me at home, and I said: “What, are you fucking kidding?” But I went to see it and I loved it - the costuming, the Victorian clothing, the staging, the music.

When Broadway came along I was playing clubs – you’d show up in the afternoon, there’s no bathroom, no backstage. So I was very happy to get on Broadway and have my own dressing room and my own bathroom. I was like: “Thank the Lord!” How do theatre people compare to rock’n’roll people? Well, that’s how I learned to drink red wine. They do the show, then when it’s done then they all go to some amazing Italian restaurant in Times Square.

You also appeared in the theatre productions The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Jesus Christ Superstar, but you didn’t pursue theatre any further. Why not? You could have been the next Michael Crawford.

Ha! Well, I was asked to do some plays that I said no to. They wanted me to play the Childcatcher in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. They made me a serious offer, but it was only one song per performance, which just wasn’t interesting to me. My agent called me up and said: “Are you fucking crazy?” I couldn’t see myself going on the website, saying: “Hey, all you fans out there, come and see me in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang!” I’m sorry, it has to have an element of rock’n’roll for me.

You’ve done some acting in TV shows such as Gilmore Girls and Californication. Have you ever been offered any properly big roles in Hollywood films?

When I was in Skid Row, I got asked to be in the [Patrick Swayze/Keanu Reeves] movie Point Break, but for some reason the manager didn’t want me to do it. They asked Skid Row to do the theme song to the movie. And when Arnold Schwarzenegger did Terminator 2, his first choice for the soundtrack was Skid Row’s Monkey Business! Arnold personally picked it. We had meetings, but again our management said: “No, we’re not doing that.” And Guns N’ Roses fucking did it! But I have always wanted to be in a Marvel movie. The only problem is they fucking stink now.

Back in the early 2000s, you auditioned to be the singer with Velvet Revolver. What are your memories of that?

Well, I still have the tape. I went in the studio and recorded five songs that I wrote with them. That was at the time I was rehearsing for Jesus Christ Superstar, and I was making a good living. It was about to go on tour for six months, and I wasn’t gonna quit that. They needed a guy, they couldn’t wait for me, so they got Scott Weiland.

Will any of those songs ever see the light of day?

I don’t listen to it much, I don’t wanna drive myself crazy, but [Velvet Revolver drummer] Matt Sorum, who’s my buddy, says to me: “Let’s put that shit out.” It’s fucking heavy, man. It’s heavy music. It’s five songs, it could make a great EP.

You were really close to Axl at that point. There was no love lost between him and Slash. How hard was it to balance the two friendships?

I used to sit up with Axl late at night and into the next morning, talking about his grievances with his former band. Around the time, [ex-MC5 guitarist] Wayne Kramer and Slash called me. They had a benefit in New York for [upmarket menswear designer John Varvatos], and Wayne said: “I want you to sing with me and Slash at this thing.” I was such friends with Axl at the time, I had to tell them on the phone: “No, I can’t do it. I don’t want to piss off Axl.” And of course Wayne Kramer is no longer with us, and I really wish I’d done it.

In 2011 your house in New Jersey was destroyed by Hurricane Irene. That must have been hugely traumatic for you.

It could not have been more traumatic. I don’t even know how to put it into words. I was opening for Twisted Sister and Godsmack in… I think it was Idaho. I came off stage and it was like: “Dude, this is really bad. Your house is destroyed, your kids were evacuated.” I got so drunk that they barely let me on the plane to fly back. The house was condemned, so they wouldn’t let me in. I went: “Dude, all the fucking stuff that I own is in there.” They looked at me and went: “You know what? Go in there, but you didn’t get permission from us.”

That’s what the song Everybody Bleeds is about. It doesn’t matter what your political affiliation is, what race you are, how rich or poor you are, the Earth is our only home, and if we don’t do something to save it we’re all fucked.

On a lighter note, in 2023 you were ‘Tiki’ in the American version of The Masked Singer. What was that experience like?

It was great. I did pretty good. I progressed through the episodes, I beat some guys in challenges and sing-offs. You wanna have a fucking sing-off with me, you better be fucking warmed up.

But you’re a professional singer. Shouldn’t you have won?

Well, I lost to Macy Gray. And, you know, the show is pretty much R&B-themed - I don’t think they wanted a heavy-metal rocker to take over the show. I did Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, I did Kiss’s I Was Made For Lovin’ You, I do Lady Gaga’s Monster, and I scream my nuts off. You go watch it, you tell me who won!

Is there part of you that wishes you’d made more records than you have done?

No, because I only make them when I have the songs to make them. The only way I would be sorry about that is if I had a bunch of songs lying around. But they’re all out there. I do wish that the original Skid Row could put aside our differences and make another record, definitely. Because we’re still alive.

I just had [former Skid Row drummer] Rob Affuso in the video [for the album’s first single, What Do I Got To Lose?]. I kept saying: “Dude, this is so cool.” You can feel the chemistry. Imagine the chemistry if all five of us were together. It would be crazy. It would just be like seeing Guns N’ Roses getting back together. Look at Slayer. If you read their interviews, they hate each other’s guts. But now they’re back together.

So what’s preventing the original Skid Row line-up from reuniting?

You’ve seen the Metallica movie Some Kind Of Monster? You’ve read the official Aerosmith biography, or Mötley Crüe’s The Dirt? All of them are about the band working with a therapist to keep the band going. Every one of them. That never happened with Skid Row. Never. It was never even discussed. Every time I read one of those books, I feel like fucking throwing it against the wall, cos it’s chapter after chapter about the band members not being able to see eye to eye, and hiring this dude for fifty grand a month to talk it out. Nobody ever did that for Skid Row. I guess twenty million records wasn’t enough to even try. It seems to me it should happen.

Do you think it will happen?

There’s no reason why not. So why not?

It’s taken ten years to put out your new solo album. Will we have to wait another ten years for the next one?

I don’t think so. I have a great team around me, I’m on a great label, Reigning Sound, which also has Kerry King and a bunch of other stuff. My management also manage Slayer and Ghost. And I do have a song for the next record. I’m collaborating on it with [former Guns N’ Roses/Sixx AM guitarist] DJ Ashba. It’s a fucking badass tune. So I got one!

When you look back at your career, what would have done differently?

Well, this answers something you asked before that I did not answer. I started so young that I was playing in arenas when I was, like, nineteen years old. I was coming from the streets, from the clubs. I did not grasp that playing for twenty thousand people you have to be more focused on your message that you’re sending out, that you’re setting an example for kids in the audience. You don’t want to hurt anyone. That’s what I would do different. But I was nineteen years old, and when you’re nineteen years old you think you know everything. And guess what? You really don’t.

All of this has made for a spectacularly interesting life, but has your music taken a back seat because of it?

Not recently, no. Maybe at periods, definitely. When I was on Broadway for six months I didn’t have any time to do anything else. My agency at the time were great at getting me on TV shows, but not so good at lining up rock tours. But it’s all different now. My agents have got me touring all fucking year. It’s all rock’n’roll now, brother!

Sebastian Bach's Child Within The Man is out now.