Memphis in the early spring of 1982 was hot, sticky and humid, same as any other year. However, change was most definitely in the air for three Texan gentlemen who had assembled in the city, however briefly, to lay down the basic tracks for what would be their eighth album.

Up till then, Billy Gibbons, Dusty Hill and Frank Beard, collectively ZZ Top, had made music together that was as true to an American tradition as pumpkin pie; music steeped in the electric blues pioneered by the likes of Jimmy Reed, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and the two Kings: BB and Albert. Yet at that precise moment, ZZ Top found themselves at a crossroads in their career. And as their leader, Gibbons at least had determined that they plough a new path.

It was Gibbons who formed the band in his home town of Houston, backed up by his dutiful manager-producer, the entrepreneurial, enigmatic Bill Ham. The first line-up of ZZ lasted just long enough to cut a single in 1969, a modest chugger titled Salt Lick, and secure Gibbons and Ham a deal with London Records. After which bassist Hill and drummer Beard, already bar-band veterans, were brought on board.

The trio’s third album, 1973’s Tres Hombres, was their breakthrough, with a string of short, sharp and soulful records following that all together made them the biggest cult band in the States. This first chapter reached its apex with 1976’s Tejas and the ensuing Worldwide Texas Tour. A 19-month-long, 96-date trawl across the US, it found them performing on a giant stage made in the shape of the Lone Star State and bedecked with such native wildlife as cacti, longhorn cattle and a pair of glowering black vultures.

Burnt out from this epic undertaking, the band broke off for a two-year hiatus, during which Gibbons roamed around Europe, Hill visited Mexico and Beard had an extended sojourn in Jamaica. The fact that ZZ Top meant diddly overseas allowed the three of them to travel in complete anonymity. Although when they returned to Texas they had secured their future indelible identity, with Gibbons and Hill having both grown out their beards.

Their 1979 comeback album, Deguello, stuck fast to formula and sold a million. But Gibbons had picked up a prototype Fairlight sampler/synthesiser on his travels and began using it to experiment with new sounds. The next album was 1981’s El Loco, upon which the band’s staple classic rock diet was supplemented by such unhinged left-field oddities as Groovy Little Hippie Pad and Party On The Patio, both mangled out of Gibbons’s new toy.

“Without question there’s some crazy, interesting-sounding stuff on that record,” Gibbons says today, from his perch on ZZ’s tour bus as it winds its way around the European festival circuit. “The intrigue of these new-found contraptions was by then just starting to catch on, but we didn’t have a teacher or guide, we didn’t even have an instruction manual. I was just pushing buttons and found something that sounded kind of trashy.”

“But we’d always done that kind of thing,” insists Hill, the cadence of his Texan drawl a beat quicker that Gibbons’s mellifluous burr. “Very early on, I walked into the studio one time and found Billy on the floor, pumping the pedals of an organ with his hands, just shadowing a bass part of mine. That was a very primitive version of what we went on to do.”

El Loco, though, proved to be too jarring for ZZ’s heartland audience and sold less than half as much as its predecessor. Hauling their unloved album around Europe later that same year, Gibbons happened into a club late one night and was struck by the spectacle of a throng of people dancing to the Rolling Stones’ elastic-limbed funk-a-thon Emotional Rescue. Gibbons’s elders by a half a decade and more, the Stones had just then recast themselves as fresh, vibrant, even sonic explorers, as his own band had got stuck in a rut of their own making.

“To me Billy is a true genius,” offers Terry Manning, who engineered ZZ’s records from Tres Hombres to 1990’s Recycler. “And not only musically, but also as a human being, if there is such a definition. He’s extremely philosophical, a deep thinker and musically very aware. He started to analyse why ZZ didn’t get played in dance clubs, and concluded that they were not up to the required rhythmic capabilities.

"He asked me what we could do. I started going to clubs and studying beats. The market had changed quite a bit from blues-based rock’n roll. So I came up with some ideas we could implement to make a very different album.”

The eventual first fruit of their labours was Eliminator, which became by far ZZ Top’s most successful and also controversial album. In total, it sounded the work of an altogether new band, but then again timeless. Eliminator was such a significant departure that it incited blues purists to accuse the band of an act of near-heresy.

Yet it has endured to such an extent that, 33 years on, it supplied more than a third of the tracks on Live Greatest Hits From Around The World, the band’s then live album. “But then if we didn’t play those songs we’d likely get strung up by our heels,” Frank Beard notes sanguinely. And if on the surface it appeared an entirely cohesive musical statement, there lurks a more convoluted, contentious truth behind the story of its making which continues to keep secrets and ferment bad blood.

In the respective tales of Gibbons, Hill and Beard, Eliminator was forged during months of close-knit jam sessions, the band bolt-holed first in Texas and then at their preferred studio in Memphis. Certainly, work started at Gibbons’s house on South Padre Island, a fingertip of land jutting into the ocean from off the Texan Gulf Coast. It was to there at the start of ’82 that Manning shipped a portable recording studio.

From there, the action moved to Beard’s new house on the outskirts of Houston. According to the drummer, for the next several weeks Gibbons and Hill would arrive at his home for one pm and they would then go down in his basement studio to drill the raw materials into shape.

“We knew the direction we were going in so weren’t flying blind,” Beard says. “The three of us would bash around till we got tired, sometimes by five pm, others we’d go on to midnight. Billy would set a sheet of paper in the middle of the floor and write out lyrics on the hoof.”

Also party to these gatherings was an associate of the band and Beard’s house guest, Linden Hudson, a former DJ, an aspiring songwriter and a sound engineer. Hudson had built Beard’s studio in lieu of paying him rent, and previously had done uncredited pre-production work on El Loco. He stepped into the same role again now, working in particular with Gibbons.

“Linden was quite an influential, inspirational figure,” Gibbons admits. “He was right there with us when some of the material was developed and brought forward some production techniques that were then valuable. I still treasure the moments that he and I spent together. There was quite a bit of time that the two of us sat behind a mixing console discussing new ways to go about making popular music.”

Nevertheless, when the following year Eliminator appeared, Hudson’s contribution was once more not credited. On this occasion, though, he took legal action, claiming to have been closely involved in both the creation of sounds and songwriting for the album.

In large part Hudson was supported by ZZ’s stage manager of 15 years, David Blayney, who in his 1994 biography of the band, Sharp-Dressed Men, wrote that “[Hudson] floated the notion that the ideal dance music had 124bpm [and then] he and Gibbons conceived, wrote and recorded what amounted to a rough draft of the album before the band had ever set foot in the studio.” Hudson’s case was settled in 1986, with the band paying out $600,000 to him after he was adjudged to own the copyright on one of Eliminator’s 11 songs, Thug.

“The whole thing was a particular disappointment to me,” Beard reasons now. “Basically, Linden was kind of a house-sitter for me. He looked after my home when we were out on tour. What happened with him was a real drag. But you have to move on.”

ZZ, minus Hudson, moved in the short term to Memphis where they stayed at a grand old hotel, the Peabody, ideally suited to a band of such quirks. Back in 1940, a former circus performer and animal trainer, a fellow splendidly named Bellman Edwards Pembroke, had coached five American ducks to parade each day through the hotel’s ornate lobby and onto the base of its decorative fountain.

More than 40 years on, Pembroke was still serving as the Peabody Duck-Master and his latest raft of avian charges continued to perform twice daily. “A lot of musicians used to hang there too,” says Beard. “There was also a piano in the lobby and I walked in one night to find Jerry Lee Lewis sat at it and playing.”

Work on the basic tracks began in Studio A at Ardent Studios with Bill Ham as producer. Housed in a nondescript red-brick store building a mile from downtown and the blues clubs on Beale Street, Ardent had played host to, among others, Led Zeppelin, Joe Cocker, Leon Russell and local boys Big Star and had been ZZ’s base of operations for every album since Tres Hombres. Gibbons claims the band kept by and large to a “golden routine”, bunkering down to each day from 9am till 9pm.

“Ardent was such a remarkable place and a great gentlemen’s club,” he continues. “Terry Manning’s name appeared on our records, but they were really the work of the house consortium of Terry, Joe Hardy, John Hampton and even the owner, Mr John Fry, rest his soul. Anybody can twist a knob, but it takes real talent to know where the sweet spot is. And when you get such a team of operators who know how to lay hands on the faders and ride gain, that’s when the magic happens.

“By then we had made the city our second home. There’s a thread of music sounds that have always been part of the Memphis scene, and that was a big inspiration that kept us on track. But Memphis is also a great trouble-in-waiting town, and of course we made the most of that, too. We would go gambling and carousing about at a dog track across the Mississippi River in West Memphis, Arkansas. Or else there were a couple of all-night, after-hours joints that were highly illegal, but where the dice games and good music would start to unfold.”

These nocturnal forrays would soon become imprinted on the album. Stuck for a title and lyrics to go with a taut blues backing track that the band had put down, Gibbons found himself in an East Memphis bar one night when “a young lady walked in wearing a painter’s white jumpsuit. As she strolled past I saw that she had the words ‘TV Dinners’ emblazoned on the back of the suit. I don’t know to this day why that was such a stimulus, but there the title of the song was.

"I went right on back to the Peabody, holed up in my room and scribbled out the words that night. Who’d have thought a rock’n’roll song would be about food?” On another occasion Gibbons dashed at 3am from an after-hours club to Ardent to cut, in a single take, two weeping guitar solos for Eliminator’s centrepiece ballad I Need You Tonight.

Other tracks had longer-reaching influences. The prompt for the stomping I Got The Six, for example, dated back to Gibbons being in London in 1977 and during punk’s high summer. There was another based around a simple, nagging, Stones-like riff that was even titled as such on the original master tape. It would eventually be called Gimme All Your Lovin’. And there was an insistent, near-pop tune that had risen up from continued prodding of Gibbons’s keyboard synth. “

We found out we could make it sound like a flat tyre going down a muddy road,” says Beard. Gibbons wrote lyrics for the song after the night the band had observed a stranded woman motorist flag down another vehicle on the freeway and he’d commented: “She’s got legs and she knows how to use ’em.”

“We’re a laugh riot alright,” Hill notes sardonically. “It seems funny now, but the few who did get to hear Legs when we were recording were kind of shocked. To put it bluntly, we got a little shit for abandoning our basic sound.”

Eliminator certainly unveiled a slicker, more polished ZZ, but the process of burnishing and enhancing their rough tracks mostly happened once both Hill and Beard had left Memphis and later still away from the confines of Ardent. Among each other, Gibbons, Ham and Manning jokingly referred to each as The Triumvirate. And it was this cabal that for the past decade had governed how ZZ’s records would ultimately end up being.

Or, as Gibbons puts it: “[On Eliminator] Frank and Dusty assigned me to the task of threading it all together. A sense of importance was placed on timing and tuning. And we spent a lot of productive hours making the most of keeping that record on a good tempo.”

“For many years the three of us were incredibly close,” says Manning. “The other two guys in the band played their roles before Eliminator, but in general they would just come, do their parts and go. Billy, Bill and I were involved in most of the production and engineering-type things. Working with Billy was always a pleasure, and especially when we got to be just one on one, the two of us going crazy back and forth, trying out sounds and different instruments.

"Bill Ham was an amazing guy, too. I would say he leaned a little more to an executive producer role. He wasn’t totally conversant on all things musical theory or technical, but he knew what he liked when he heard it.

“A lot of that record ended up being done in my home studio in Memphis. It was a full twenty-four-track with a big desk and everything, but literally in my attic. For ninety-nine per cent of the time it was only me there, nobody else. Bill came over one time, and Billy, too, but just to add a little guitar piece.”

- Listen to ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons cover Muddy Waters

- ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons announces new solo album The Big Bad Blues

- The 10 Best ZZ Top Songs, by Billy Gibbons' protege Lance Lopez

- 20 of the Greatest Rock'n'Roll Movies Ever Made

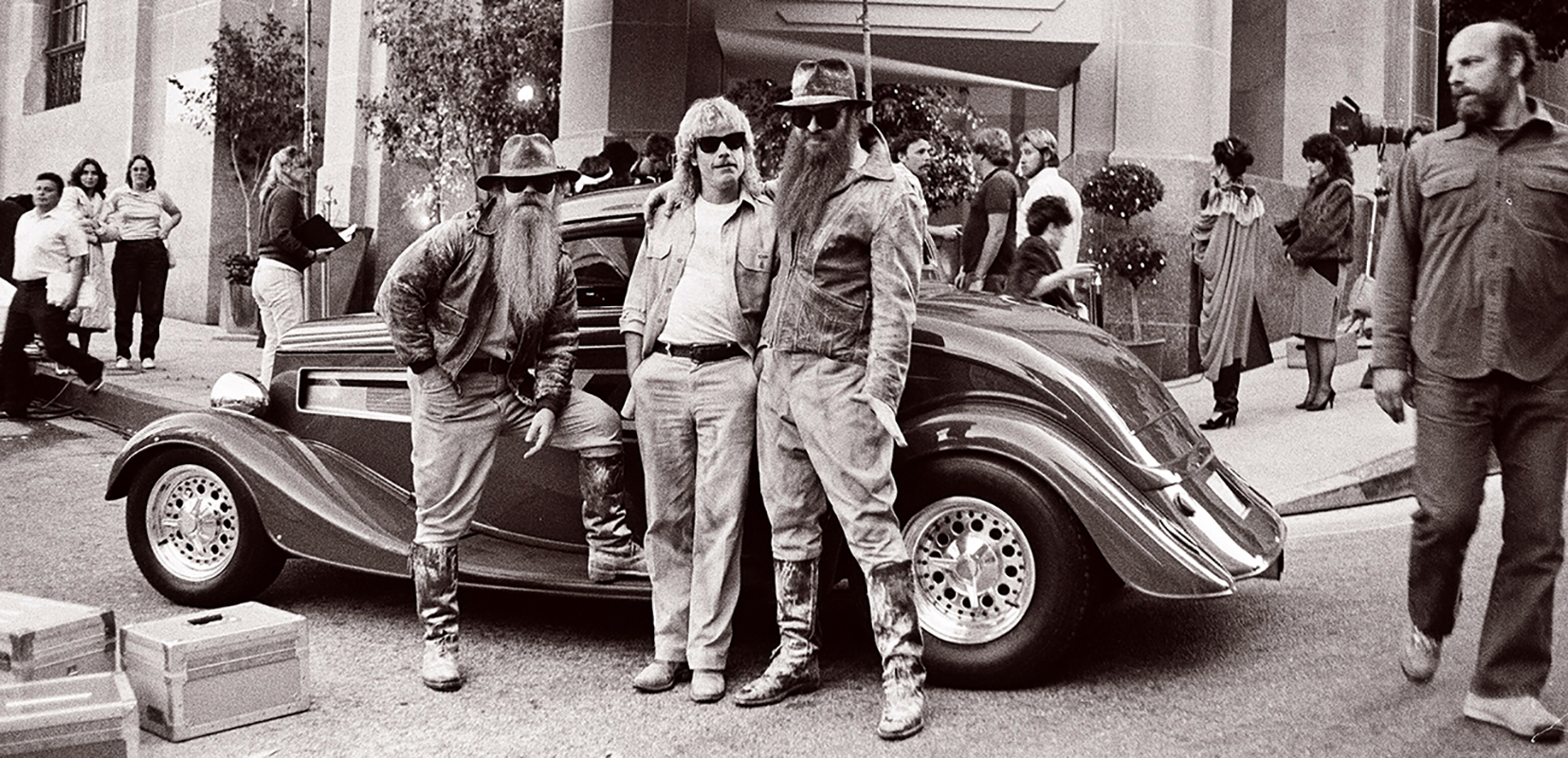

After close on a year’s recording and then fine-tuning, Eliminator (a term for winning a drag race), was released on March 23, 1983. Suitably revved-up and high-octane, it was also appropriately wrapped in a cover depicting a racing-red 1933 Ford coupe with a Corvette engine that had been custom-built for Gibbons out in California. Using the car as a prop for the band had allowed the guitarist to write off the cost of it against tax. It also took a lead role in the medium through which Eliminator would explode as a genuine phenomenon.

On August 1, 1981, just one month after El Loco had emerged and been released, a new, 24-hour TV music channel launched in the US. At a stroke, MTV changed the rules of engagement for the music business, placing as much of an emphasis on high-concept videos and image as on songs.

That year of 1983 alone, the channel was the medium through which Madonna was first introduced and Michael Jackson’s Thriller shot into global consciousness. At Bill Ham’s behest, ZZ Top also exploited this fast-developing opportunity to the full. Perceived up to that point as hoary old rockers, with their beards and dark glasses Gibbons and Hill especially could now be made to appear not just ageless but also as otherworldly beings.

Ham commissioned a young TV commercials director, Tim Newman, to shoot three videos for Eliminator’s signature singles: Gimme All Your Lovin’, a stuttering blues, Sharp Dressed Man and Legs. Shot at a windswept gas station in the small LA County town of Littlerock, the Gimme All Your Lovin’ promo would go on to win Newman an MTV Video Award and established the key elements of an unfolding campaign – Gibbons’s car, the golden ‘ZZ’ keychain on its starter key, the band in the guise of comic observers, and the so-called Eliminator girls, principally dancer and model Daniele Arnaud and Jeana Tomasino, a Playboy Playmate.

“Tim was a great director,” says Gibbons. “By which I mean to say he told us we weren’t much to look at and so we’d need some pretty girls in the mix to sweeten up the story. He brought along a picture book of models to our first meeting. I said to him: ‘Well, slow down here and let’s take this page by page.’

“When luck is on your side things just seem to happen at appropriate times,” Gibbons continues. “Like the headless guitars we used in that video. The guy who does our guitars to this day, Mr John Bolin, told us we’d need something different for television. John had a lumberjack’s saw, so Dusty and I took our perfectly good instruments over to him and he cut the tops off them. Somehow, all of those elements seemed to end up making perfect sense.”

Coinciding with the Gimme All Your Lovin’ video debuting on MTV, ZZ Top opened their Eliminator tour in Lake Charles, Louisiana on 7 May. It would stretch out for nine months and cover the US and Europe. It also set the band the painstaking challenge of replicating their multi-layered new sound on stage.

The solution proved to be a compact eight-track tape recorder built specifically for the purpose and also operated by Terry Manning. “I called it the Tap-A-Top-22, that being ZZ backwards,” Manning says. “It was a tough process, because the band didn’t really play natively in the way Eliminator had turned out. They would come up with a set-list, and I would go through and get sounds and beats to fit the songs taken from the actual four-track master tapes. I edited them as required, for instance if they wanted to extend a particular song live.

“On the tour, I actually cued the band live with those things. One of my eight tracks was a stage cue where I would have a mic and yell out: ‘Bridge!’ which the band would hear in the stage monitors only. There were also lighting and stage automation cues. It was quite a thing to pull off – and I’m not sure that it always worked.”

Though by the start of the next year, the success or otherwise of ZZ’s live shows had long-since become almost incidental to their own outsize characters, blown up by blanket exposure on MTV. Their third video, Legs, sealed the ascent of the self-styled ‘little ol’ band from Texas’ towards becoming a household name.

In this clip, 21-year-old Wendy Frazier is seen transformed from mousy shoe-shop assistant to defiant sex kitten, and Gibbons and Hill tout sheepskin-coated guitars fitted with motors that enabled them to be spun through 360 degrees. “First time I tried it, of course, I knocked the shit out of myself upside the head,” Dusty Hill remembers.

“There was one very special moment that occurred in the UK not long after Eliminator came out,” Gibbons relates. “The BBC screened a marathon music video night, and Gimme All Your Lovin’, Sharp Dressed Man and Legs were broadcast in rapid succession just as the pubs were being let out. Right there, the entire country discovered this band of renegade misfits. We went on and had a runaway success.”

“When Legs popped, everything went kind of fast and furious,” says Hill. “As Billy likes to say, some people put on a false beard as a disguise, but we couldn’t do that. Frank pretty much stopped hanging with me, because I would draw crowds wherever I went. But you can either enjoy a thing like that or let it eat you up. We decided to enjoy it. And it was a hell of a ride.”

To date, Eliminator has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide. Further, it had a near-instantaneous and profound effect on how rock records would be made to sound through the 80s and beyond and using newly available technology. Even the Rolling Stones appeared to have sat up and taken notice, since by that November, 1983, they had fashioned an up-tempo, high-gloss hit album of their own, Undercover. But Terry Manning, for one, believes Eliminator also had a counter impact.

“Of course, it’s always great to be associated with something that turns into a worldwide hit, and it did influence what came later in music – some for the good but some for the worst,” he suggests. “Unfortunately it may have helped contribute to the downfall of rock’n’roll, because of how other people started using machines and things.”

Two years later, ZZ Top followed up Eliminator with a virtual re-run, Afterburner, but have ever since gradually pedalled back towards their original roots, as was evidenced by 2012’s La Futura, a typically bare-boned Rick Rubin production. It is Eliminator, though, that was the bed-rock of the band’s well-received Pyramid Stage set at Glastonbury, and will go on being for just so long as they continue to hit the road.

Whenever their itinerary takes them next to Cleveland, Ohio, Gibbons will, as is his custom, drop in at the city’s Rock And Roll Hall of Fame museum where his 1933 Ford Coupe is now on permanent exhibit. And when he speaks of that impending pilgrimage, Gibbons might also be summing up the staying power of the album from which the car took its name. “If we happen to be in the neighbourhood I’ll go by, crank it up and take it out for a spin,” he says. “It’s still a hot-rod, that’s for sure.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 227, in July 2016.