"We don’t bother with beds in our hotel rooms now,” Lemmy told me as I stuck another large Jack and Coke on the table in front of him. “We tell them to take ’em out.”

“Why’s that, then?”

“Cos we don’t sleep.”

I laughed at the joke, but he just gave me that gimlet eye that could freeze a penguin’s chuff.

“The only time I use a bed on tour is if I’m with a bird,” he explained matter-of-factly. “Even then I don’t really need one. Back of the bus does very nicely thank you. Also, that way I don’t have to keep taking off my boots.”

“Yes,” I murmured. I could see how that might be useful.

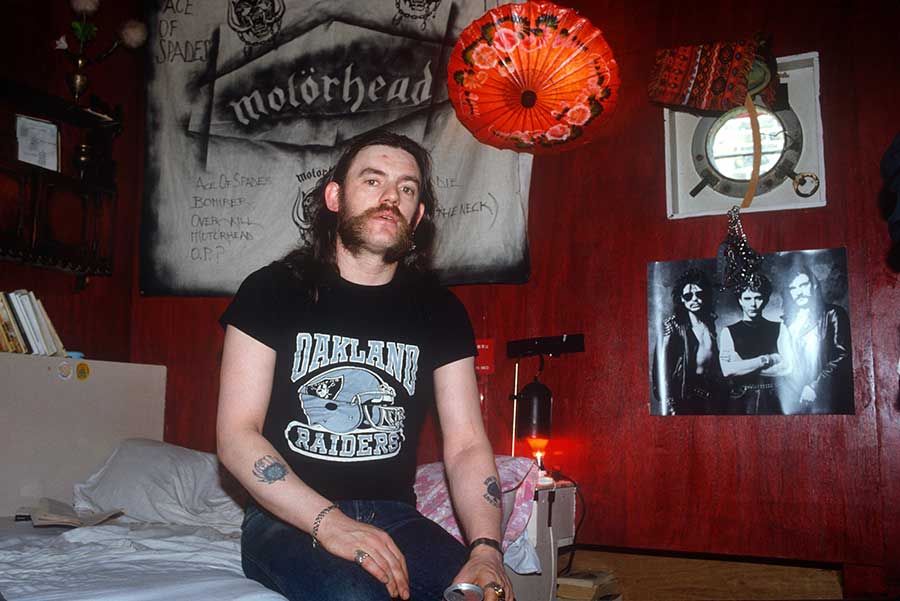

I glanced down at his old white boots. They didn’t look like they’d been taken off since the day he first put them on. It was a thundery grey evening in the summer of 1980, a few days before Motörhead were to begin recording a new album, their fourth, which they would name Ace Of Spades.

We were sitting in a pub by the canal in Westbourne Grove, West London, next door to the office of his then manager Doug Smith, who I worked for as the PR for The Damned and Hawkwind, who Doug also looked after. Doug also had a new all-girl band called Girlschool, who had just released their debut album, which everyone loved, including Lemmy.

The subject of beds and hotel rooms and, indeed, ‘birds’, had been arrived at when I tried to tease Lemmy about his extracurricular exploits the week before, when Motörhead had headlined what was billed as the Heavy Metal Barn Dance at Bingley Hall just outside Stafford.

With a capacity of 12,000, Bingley Hall was then the biggest indoor music venue in Britain. But it was strictly old-school: no seating, cold concrete floor, huge stage, no screens, nowhere to park outside, you had to fight to get in and you had to bust your way out again. If you thought you were hard enough. And you were still conscious.

Promoted as the first big New Wave Of British Heavy Metal jamboree, also on the posters were Girlschool, Vardis, Angel Witch, White Spirit and, in the Special Guest slot, effectively warming up the crowd for Lemmy’s headliners, Saxon. Which was a significant accomplishment for Motörhead, considering Saxon had just had a top-five album with Wheels Of Steel and a top-20 single with 747 (Strangers In The Night). Seen as front-runners of the now erupting NWOBHM scene, Saxon would never be so cool or so successful again.

Motörhead’s latest album, Bomber, released nine months earlier, had also been a big-ish hit, peaking at No.12. They also had a single riding high in the charts that summer, a live four-track EP titled The Golden Years, which, despite getting near-zero radio play, had lifted Motörhead into the Top 10 for the first time.

But those were just numbers. Motörhead had something going for them that neither Saxon nor any other NWOBHM acts had: they were already legends. Lemmy since his days being the speed-freaking, biker-vibing, scary-looking fucker in Hawkwind, who helmed their only hit, the single Silver Machine, in 1972.

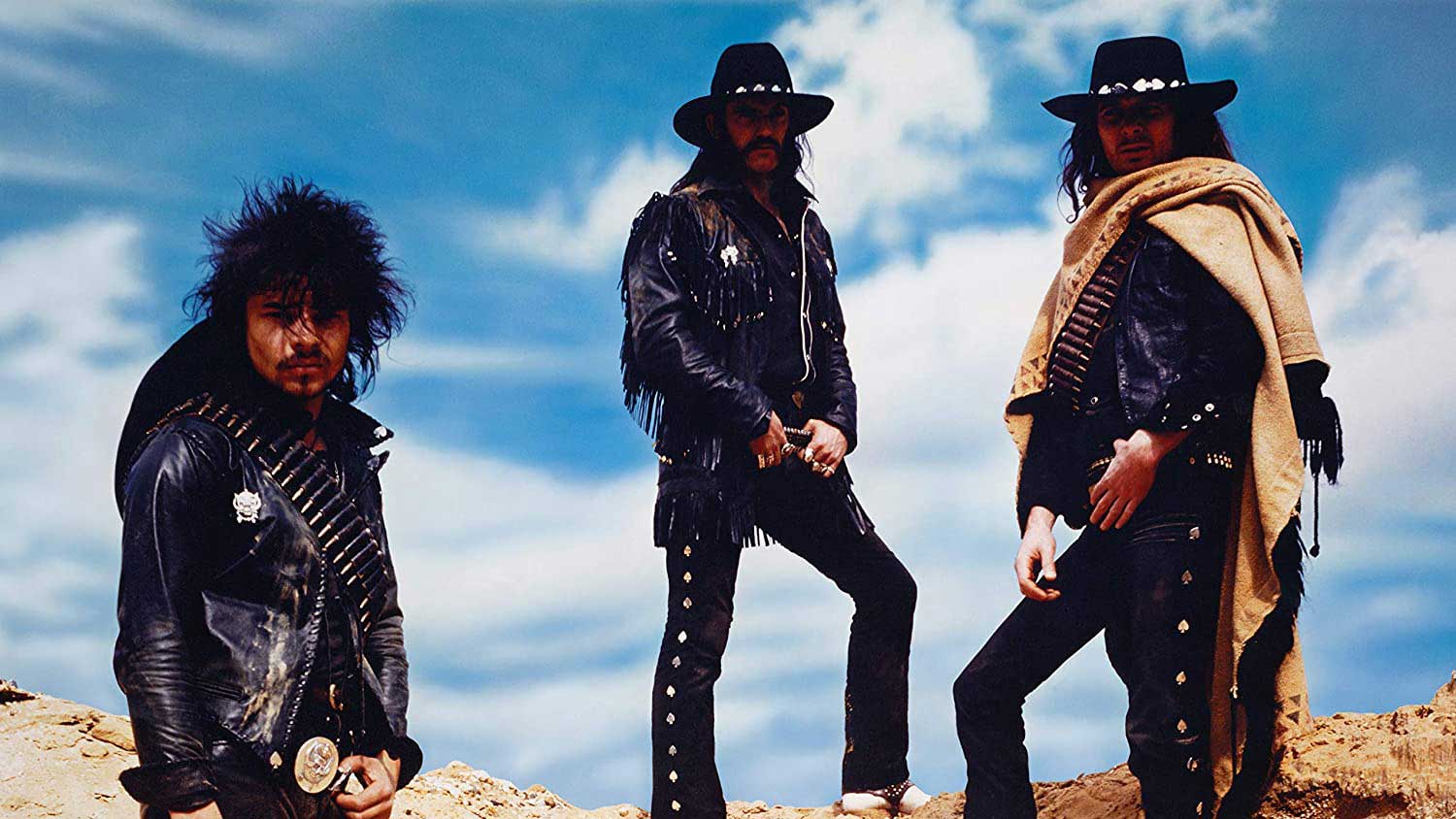

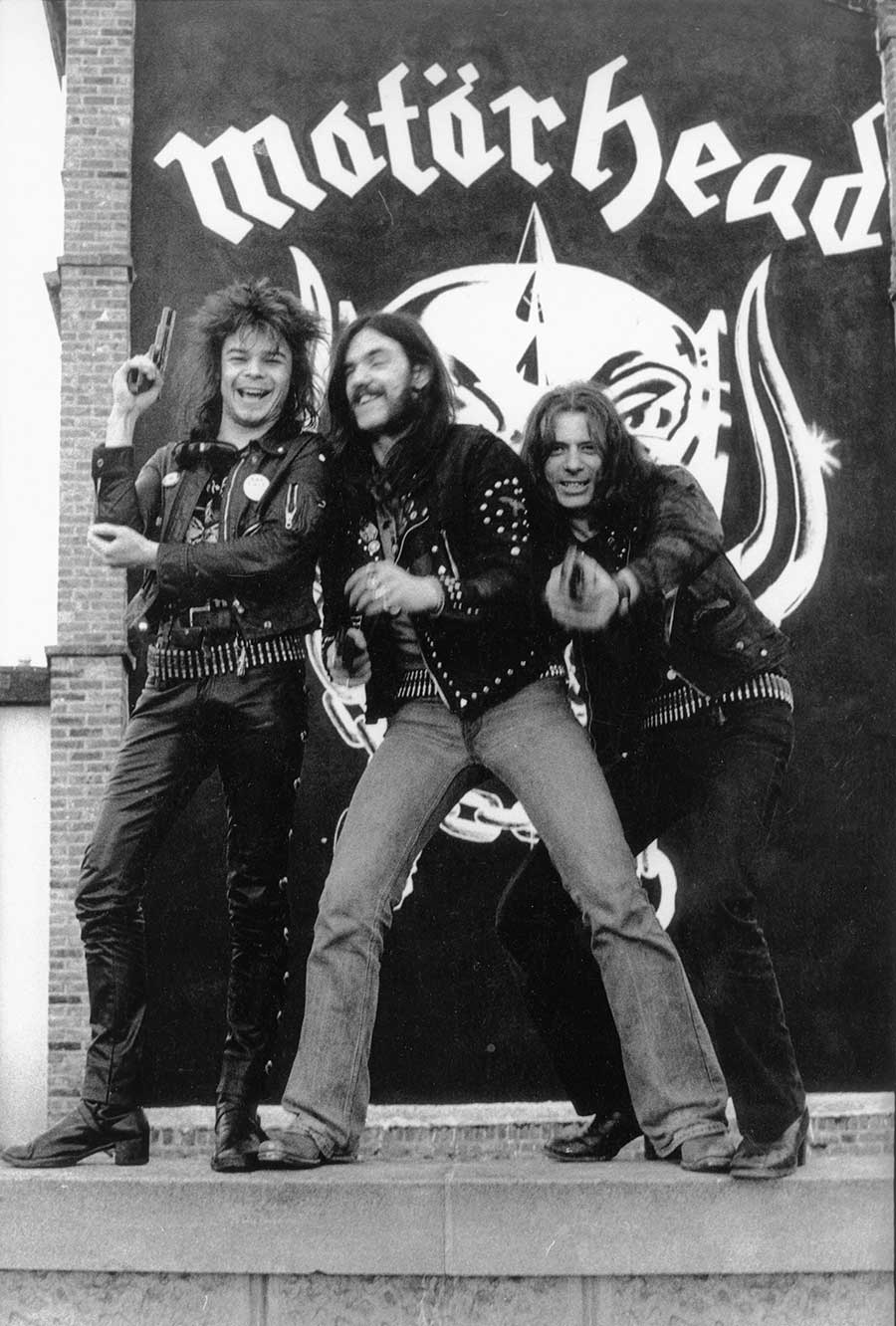

In Motörhead he was joined by the non-ironically named ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke, whose knife-stabbing guitar and long, unmade-bed hair had made him the perfect counterpart to Lemmy’s evil elder brother, musically and image-wise. Accidentally catching the spirit of the post-punk times, Eddie was as different from the clichéd guitar martyrs of the 70s as any of the new-wave anti-heroes. He could have been in the Sex Pistols or The Damned – if he’d been prepared to cut his hair. But then of course he’d have had to kill you.

As Eddie told me: “I’m not a virtuoso, I’m a journeyman. But Eric Clapton never came up with Overkill or Bomber. My job was giving Lemmy something to sing over. And we were a great team like that.”

No arguments allowed. Then there was their maniacally gurning, jackhammer-limbed drummer, the non-puzzlingly named Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor. Everyone knew all the best drummers were badasses: Moon was already dead, Bonham was just a few months from joining him, Bill Ward had just stormed out of Sabbath… It was the nature of the beast. The number. But ‘Philthy Animal’ created his own special place in the drum-or-die pantheon.

Phil was the kind of shirt-off, sunglasses-on, dagger-haired kit killer who didn’t need fame and fortune to give him permission to put the fear of God into every room he walked into. A self-admitted “hot head”, he was simply born that way.

“I met Lemmy through speed, really,” Phil told me happily. “You know, dealing and scoring.”

A former skinhead and Leeds United football hooligan, whose father had bought him a drum kit as a last resort, telling him: “If you wanna beat something up, beat this up”, Phil had met Lemmy in London, via the Hells Angels, living in various squats around West London.

What really made Motörhead special, though, was the unshakable feeling that this was a one-time ride. That they could fuck it all up any time they wanted. By the time they got to Bingley in 1980, the cracks were already appearing. Playing the biggest show of their career so far, Lemmy collapsed halfway through the set, forcing them to cancel the rest of the show. Eddie was still spitting blood about it years later.

“Lemmy had been up for days knocking back vodka and doing speed,” he recalls. “At the same time he’s been fucking chicks non-stop. We’ve got twelve thousand kids going nuts waiting for us to go on, and he can barely stand up! People had been offering me lines of coke all day, but I’m turning it down saying no, we’ve got this gig, I better keep it together.”

Barely an hour into the set, “Lemmy disappears backwards, collapses on the stage. Me and Phil were furious! ‘You let us down, you c**t!’ He’s going: ‘Me being up for three nights has nothing to do with it.’ No, of course not…”

The show itself received an ecstatic review in Melody Maker, the writer seemingly viewing the whole thing as the most marvellous theatre. For Motörhead had something none of their closest rivals had: cachet. Kudos. Kool. The media, so wilfully unavailable to heavy metal on principle, always made an exception with Motörhead. And not just because those nasty bikers who followed the band around might come after them if they didn’t.

Like Phil Lynott and Thin Lizzy, Lemmy and Motörhead had been bestowed honorary punk status. Like Lemmy, the punks ate speed for breakfast, and like Motörhead their brutally cropped, no-quarter songs largely amounted to one simple but heartfelt message: “Fuck you, we don’t care.”

“I always thought we had more in common with The Damned than Judas Priest,” Lemmy told me. “Sid Vicious begged me to teach him bass. I tried, but he was fucking useless.”

In truth, Lemmy was an old hippie who liked to hang out with everyone. Unless they rubbed him wrong, then he turned into the guy people saw when he swaggered around on stage, flicking his long black hair like a whip.

By 1980, however, the story had moved on. Against the predictions of all except the seriously stoned, Motörhead were now a big chart act. Although Lemmy was loath to admit it, for the first-time the pressure was on for them to come up with something that would take them all the way to the top. “We never look at things that way,” he insisted. “It’s not like me and Eddie go out of our way to write hits. We’re not fucking ABBA.”

Nevertheless, while it was true that any resemblance to Björn and Benny was largely undetectable, the fact is that by 1980 Lemmy and Eddie, as co-writers, had come as close as Motörhead ever would to a winning hit formula.

The trick, Eddie explained, was: “You’re bombing along having a ball, then as you’re having a ball you put a couple of little changes in, and next thing you’ve got a song.” Lemmy would leave the lyrics until last, often retreating to the toilet with pen and notepad.

“I wrote the lyrics to Ace Of Spades sitting on the bog,” he confirmed. “I had the title. I usually started with something that sounded like a good Motörhead title, then took it from there.”

It was an idea Lemmy had been thinking about for a while. He already had an ace of spades tattooed on his left forearm, along with the legend ‘Born To Lose – Live To Win’. Now, though, he would turn what was known as the ‘death card’ into the song that would later serve as his epitaph, along with its self-immolating kiss-off: ‘That’s the way I like it baby, I don’t want to live forever.’

Although Phil was always credited as an equal co-writer, according to Eddie that was only because “we didn’t want Lemmy and me coming to work in Rolls-Royces and Phil on a pushbike”. That notion belied just how important Phil’s playing was to the classic Motörhead sound, not least his spectacular double kick drum technique that would become the bedrock of what the world soon came to call thrash metal.

Or as Metallica drummer/founder and former president of the US Motörhead fan club Lars Ulrich once told me: “Phil Taylor was the first drummer I ever heard play that double bass drum type of thing. The first time I first heard Overkill it fucking blew my head off. I could not believe what I was hearing. Of course, then I wanted to play like that too.”

Indeed, Ace Of Spades would be built around Phil’s ferociously philthy double kick drums. This despite an initially exasperated Lemmy yelling at him: “Fucking hell! Can’t you play a straight four?!”

But then, as Eddie gleefully pointed out, Lemmy’s bass could also be “fucking difficult” to play along with. “Because there was no bottom end! Especially in those days, a bottom end on the bass was how it was played. Well, we didn’t have any. So that made life very, very tricky. Until we got the hang of it, which we finally did on Ace Of Spades, but only then because the producer, Vic Maile, insisted on it.”

On the surface, the quietly spoken, meticulously organised Maile seemed an unlikely co-conspirator for Lemmy and co. But his years of working in the studio with big names including The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin and Clapton meant he was impossible to intimidate. The fact that was he diabetic meant he didn’t indulge in any of the band’s extracurricular habits, either.

“I couldn’t make him out at first,” Lemmy said. “He had to have his tea breaks and his biscuit cos of his diabetes or whatever. But he turned out to be a hard man in his own right. It was Vic that got Phil to slow down and focus on his drums, explaining the difference between playing on stage and in a studio. And it was Vic who got me playing the bass the way a bass player would. Or at least enough like a bass player that it made all the difference. Until then I’d always played it like another guitar.”

There were some bad habits that even Vic Maile was unable to improve on, though. Eddie recalled that before starting work “we’d have a little toot. Then a bit later you’d do a bit more. The only problem was when we didn’t have any speed. Me and Phil were not so bad, we could live without it, but Lemmy couldn’t. He used to get flu and all sorts. Trying to get him to work without any speed around was very difficult. And a lot of arguments came out of that. It did create bad blood at times. We’d begin recording and Lemmy wouldn’t be there.”

Despite all this, when they’d finished recording, in September, they left the studio with what would be the last of the true Motörhead masterpieces

There are 12 tracks on Ace Of Spades, six of them under three minutes long, only one of them over four, all of them great ’Head-giving tracks, three of them absolute Motör-classics: the title track plus (We Are) The Road Crew and The Chase Is Better Than The Catch. The title track, of course, would go on to become the band’s signature song, like Smoke On The Water for Deep Purple or All Right Now for Free.

By the time of Lemmy’s death 35 years later, Ace Of Spades was still the one song everybody knew him by. The one song no Motörhead show would ever be complete without. With its rumbling-thunder bass, lightning-fast drums and speedy, corner-hugging guitar riff, overlaid by a thrilling lyric in which gambling metaphors become code for how to live your life to the full, Lemmy outdid himself this time – although, as he was always quick to point out, he was never much of a poker player in real life, always preferring the swinging arm of the fruit machines (one of which he now had installed in the dressing room each night on tour).

Thus we hear about ‘snake eyes’ – double one on gambling dice – and the ‘dead man’s hand, aces and eights’, which as Lemmy explained was “Wild Bill Hickcock’s hand when he got shot.” Cue that fearfully cackling, gloriously insane solo As Eddie recalled for me just a few months before he died: “The way Lemmy’s lyrics had improved was amazing. For fuck’s sake, he was improving all the time. Once we’d cracked the little formula of how to really work together, on Overkill and Bomber, we really started to take off.”

Wouldn’t that line about not wanting to live forever come back to haunt Lemmy one day, though? The way Pete Townshend’s line in The Who’s My Generation – ‘Hope I die before I get old’ – eventually did?

“Of course!” he said, laughing. “But, see, I cover a lot more ground than Townshend. ‘I don’t want to live forever’ is a long time. You could be 294 and not reach ‘forever’. But I think you’d be sick of it by then. I think anybody would. Even me. And I like to stay up late, you know?”

He paused, relit his joint, puffed a cloud of smoke in my face and concluded: “Actually, I’d like to die the year before forever. To avoid the rush.”

The other major cornerstones of the album also embraced tenets of Lemmy’s personal philosophy. The most affecting was (We Are) The Road Crew. Having once been a roadie himself (for Jimi Hendrix), Lemmy always felt an affinity for the hard-working crew who gave their all on tour for Motörhead. Lemmy later recalled how when one of his roadies, Ian ‘Eagle’ Dobbie, first heard the song “he had a tear in his eye”.

More rowdy and to the point was The Chase Is Better Than The Catch, which drew bile from several female rock writers, as did Love Me Like A Reptile and Jailbait.

Eddie couldn’t see what the fuss was about. “It’s about the true life experience of what it’s like being in a band like this,” he said. “When you haven’t got a pot to piss in and you’re slogging around the country and having a laugh, you haven’t got time for thinking. If you got a drink and a joint and toot you figure your fucking life’s sweet, man, and a bird’s sucking you off, what more do I ever want?”

On the road, at the end of another long night of not sleeping is “when everybody becomes good looking”, Lemmy explained. “But sometimes it’s like there’s the last chicken in the shop and you don’t seem to be able to help yourself. It’s like having an out-of-body experience. You see yourself chatting up this dragon, and you know you’re doing it, but you still do it.”

What Lemmy was less inclined to talk about was how he had tried more than one close relationship with a woman. His last had been with a live-in partner named Jeanette.

According to Eddie: “They had some terrible fights. I think she just used to wind him up. As women do, you know? And he just got fucked off with it in the end. He said: ‘I ain’t fucking doing that no more.’”

“I’m not against the idea of finding the right one and settling down,” Lemmy told me. “I’ve just never been able to find a girl that would stop me chasing all the others.”

As Eddie put it: “Phil was no different. To be honest, the three of us were all the same when it came to birds. It’s why we were so perfect. We never settled down. We were what we were. That’s why we were so right for each other.”

When Ace Of Spades was released as a single in October, despite little or no airplay again, it rocketed into the UK chart at No.15, triggering yet another Top Of The Pops appearance and yet more music-weekly front covers. What really hit home for Lemmy, though, was when the Ace Of Spades album went straight into the chart – at No.4!

“That was it, really, “ he told me years later. “We thought we’d made it. And actually we had. And that’s when we started to fuck up. Not all at once, but that was probably the start.”

It was little things, at first, Eddie said. “Phil always had this thing about everybody being equal. Phil always used to get the hump about Lemmy sitting in the front of the car. But I never gave a flying fuck. I never minded Lemmy having his edge. That was fine with me. He was Lemmy and that was okay with me. But it used to get up Phil’s nose a fair bit.

“These things don’t happen until you get successful,” Eddie continued. “But what happens when you start to become famous, and suddenly you get a bit arsey or something pisses you off, you think: ‘I don’t have to put up with this, I’m famous!’ I never felt like that, but I think both Phil and Lemmy did a tad.”

Suddenly there were “business hassles too”, all of which Eddie now took upon himself to try to resolve. Most glaringly, when manager Doug Smith rang Eddie “on the eve of the Ace Of Spades tour, to say the promoter couldn’t come up with the 118,000 pounds we’d agreed to do the tour, and that the tour would have to be cancelled unless we agreed to lower the price to 108,000.

"I told the boys, and we were like: ‘Fuck that!’ But we would have done anything rather than cancel a tour. Our attitude was: ‘We can’t do this to the fans. Doug knows this, so he’s got us over a barrel. This is two days before the tour is supposed to kick off.”

Once what should have been a victory-lap tour had started, the band suffered more bad luck when Phil either fell or was thrown – depending on which speed freak you can stand to listen to for long enough – down the stairs of his hotel at an early date and landed on his head.

At first they feared he’d broken his neck. Fortunately, it turned out to be only his vertebrae he’d damaged. As a result of the injury, he was forced to get through the rest of the tour playing with a neck brace on. Things only got more difficult when between April and July 1981 they took off for their first major US tour – 42 dates across North America and Canada, some opening for Ozzy Osbourne in arenas, others headlining their own smaller club and theatre shows – that would test the band’s resolve to its limits.

Ace Of Spades was the first Motörhead album released in the US, and hopes were high for a repeat of the success they were now enjoying in the UK. But American radio had made it clear they weren’t going to sully their airwaves with such motorcycle filth, so it was down to hard roadwork to try to promote it.

Lemmy, who hadn’t been back to America since being fired from Hawkwind on the Canadian border five years earlier, relished reacquainting himself with a country he had already decided he wanted to go and live in one day. “If I could do, I’d just do a never-ending tour of Los Angeles,” he told me, only half-joking.

Neither Eddie nor Phil had been to America before, and so viewed the start of the tour as the beginning of a great new adventure. But the novelty soon wore off as they found themselves either being catcalled and booed by Ozzy’s drunkenly partisan crowd, or playing to largely empty rooms at their own shows.

“The Americans were not ready for Motörhead,” Eddie solemnly proclaimed. “We didn’t get a single encore for about the first four weeks.”

The three of them began to pick at each other. Especially Eddie and Phil, who spent most of the tour permanently at each other’s throats.

“The fights between me and Eddie were legendary,” Phil laughingly told me. “We’d really try to hurt each other.”

The US tour became so stressful that Doug Smith considered cutting it short. “I once thought Phil Taylor was dead of an overdose in New York,” he recalled. “And in America the police arrive whenever you call an ambulance, so I’d been going around his room hiding every drug I could find, hoping they’d think he’d just collapsed of exhaustion. It was life-threatening all the time, for all of them – even Lemmy, who I once thought was gonna have a heart attack when we got to a gig in Canada and there was no speed around.”

What made it more difficult in America was the knowledge that back home in Britain they were now big stars. So much so that in February, when their label Bronze released a three-track EP featuring both Motörhead and Girlschool, titled St Valentine’s Day Massacre, it became the band’s biggest-selling record ever, reaching No.5 and selling more than 200,000 copies

Lemmy, who it was whispered was ‘very close’ to Girlschool’s blonde bombshell guitarist Kelly Johnson, was delighted. The result: yet more appearances on Top Of The Pops – this time with Girlschool alongside them, the two bands billed as Headgirl – playing the lead track, a fantastically bottle-smashing cover of Please Don’t Touch by Johnny Kidd & The Pirates, one of Lemmy’s personal favourites. (The other two tracks on the EP were Motörhead covering the Girlschool original Emergency, with Eddie, er, ‘singing’, and Girlschool covering Bomber.)

If touring America, playing to audiences that didn’t give a shit, while promoting an album no one had heard of was dispiriting, at least they had the consolation of knowing that in Britain the band were now approaching National Treasure status. It wasn’t only Top Of The Pops that Motörhead now became regular faces on. They were being invited onto children’s TV shows too, most memorably the blissfully anarchic Tiswas, where they were interviewed by the ‘bubbly’ Sally James, thoroughly ‘flanned’ by the Phantom Flan Flinger, then hosed down with water by various members of the cast including Chris Tarrant and Lenny Henry.

At the time, appearing on Tiswas had become the mark of cool for any self-respecting rock band. Motörhead would return and make several appearances, blasting out bits of Bomber and Ace Of Spades as the kids in the studio bounced around them frantically. “Doing that show probably brought in more fans than if we’d done a gig in Birmingham [where the show was made],” Lemmy mused.

The best was to come, though. At the end of June, Motörhead were in LA, still touring with Ozzy, when Doug phoned with the news that their new album – a stop-gap live album they’d jokingly titled No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith – had just gone into the UK chart, in its first week of release – at No.1!

“The No Sleep title came from the British leg of the Ace Of Spades tour,” Lemmy explained. “We had it painted on the front of one of the trucks, because we had fifty-two gigs on that tour and only two days off: No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith.”

Whatever elation he felt at that moment had worn off by the time the band arrived home, though. “I knew there was only one way to go after that,” Lemmy said. “And I was right.” But that’s another story. For as Lemmy sang on his most famous song: ‘Win some, lose some, it’s all the same to me…’ And so it would remain.

The 40th anniversary edition of Ace of Spades is out on Oct 30.