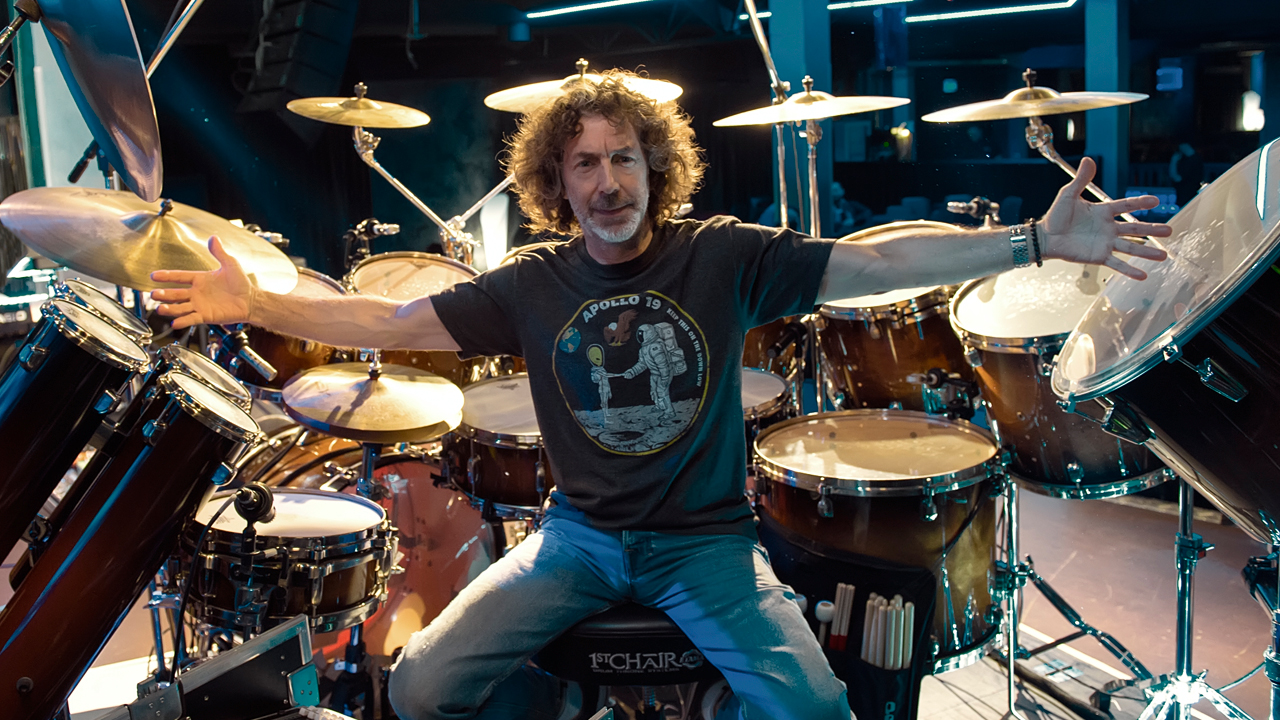

It’s easy to tell when Simon Phillips is in town. At Ronnie Scott’s, it’s impossible to miss Phillips’ mammoth 17-piece drum kit that threatens to spill off the stage into the audience, and his extraordinary ambidextrous playing is similarly unmistakable.

Emerging as a top session drummer in London in the 1970s, Phillips moved to California to join Toto in the 1990s and has been there ever since, working as a drummer, engineer and producer.

Parallel to his session playing, Phillips launched his solo career with the 1988 Protocol album, but didn’t return to the name until 2013’s Protocol II. Now he’s out on the road to support the fourth album under the Protocol banner. With much of his life spent living out of a suitcase, he’s adapted to writing music on tour.

“It started off on the last album: the song Catalyst was mostly written on a plane without a keyboard, straight into the computer, literally dragging and putting notes in on the MIDI stave,” he says. “The cool thing about that is you rely purely on your ears for harmony, instead of defaulting to shapes on the keyboard. If you’re a limited keyboard player like I am, extremely limited, you tend to just repeat those shapes. When you don’t have a keyboard in front of you, you’ve got to literally imagine the keyboard and the intervals between the notes, so it’s great. And it helps because you’re writing melody down instead of coming up with a really cool harmony and putting the melody on top.”

Despite the virtuosity in the Protocol band – the current incarnation live boasts Greg Howe on guitar, Ernest Tibbs on bass and Otmaro Ruiz on keys – Phillips never wants the music to be about busting chops.

“If you think of any of Paul McCartney’s songs, it’s always the melody,” he says. “There’s something to be said about great songs, pop songs. From Don Henley, Billy Joel, whoever it is, it’s the melody, and the problem with jazz and fusion is sometimes the melody is secondary.”

Then there’s the funky side to Protocol’s progressive fusion, which Phillips says is “always important, especially when playing complex music. That’s always the problem I had, in a production sense, when people come to me and they have incredibly complex music. I end up going, ‘It’s great, it’s clever, but there’s no groove,’ and that’s when I pull a song apart, like I did with Derek Sherinian. ‘This doesn’t need to be in 17, it can be perfect in nine and it can groove.’

“It’s something I think I’m very conscious of, especially with my own writing, that first and foremost, even with the complex stuff, there’s still a groove. You can basically tap your foot all the way through.”

Bringing new people into the fold – Howe and Ruiz came in after the departure of Andy Timmons and Steve Weingart – means the band members have to discover whether they click not just as players, but as people too.

“You never really find that out until you go on the road,” says Phillips. “First tours are usually fantastic and it’s always the second tour that the familiarity sets in and then you see how some people are because they get a little more comfortable with everybody. The honeymoon is over.”

He describes the current line-up as “the most chilled band I’ve had”, and they’ve been travelling in close quarters, with the drummer often taking the wheel – and testing everyone’s nerves.

“For the first part of the tour I had a Renault Espace – I was doing the driving,” he says. “I like to drive quickly so I’m always checking, ‘Okay, is everybody cool for hyper drive?’ ‘Yeah, okay.’ So the next day I’ll speed it up a little bit just to get everybody’s confidence and then suddenly we’re doing 180 down the freeways in Europe and everybody is cool.”

Touring jazz clubs with Protocol has to be a different experience to his time playing arenas with Toto, Jeff Beck and The Who, but Phillips believes it’s all about adapting to the venue and not losing focus on what really matters.

“My head isn’t in the rock’n’roll thing any more in terms of needing this, needing that – my head is in playing music and making it work,” he says. “If you ask any of the older drummers that have been around for years, they’ll always say, ‘Play to the room.’ If the room is small and reflective, you’ve got to change the way you play. You’ve got to be respectful and mindful of the acoustics.

“There’s always a tendency when it’s not working out to play harder, but you’re hitting a brick wall. It ain’t going to get better. You have to go the other way, just lighten up a bit and let the music play itself. Don’t try too hard.”

To illustrate his point, Phillips recalls a recording session he engineered. “It was Brandon Fields on soprano, Dave Carpenter on upright, Peter Erskine on drums and the artist was an Italian piano player,” he says. “We did one take, and Pete said, ‘Okay, let’s do another take. This time let’s try not to impress each other.’ I was in the control room almost on the floor laughing. He counted it in and it was a beautiful take. It was very cool what he said. Just play the music.

“That’s the thing you have to do in those scenarios when it’s a rough-sounding room. I always try to tell musicians who play in the band if they sometimes get too caught up in the way its sounding or making mistakes, I say play a mistake, make it work. That’s the whole thing about jazz. Make it work and let it go. It’s not the end of the world.”

Although he’s been out of Toto since 2014, Phillips still finds that band’s fans coming to his shows now. Never just the drummer in the group, Phillips engineered three of their albums and was involved in the songwriting process too – but that was always part of the appeal.

“That’s why I thought I’d probably never join a band unless it was my own band because, in order to be fully engaged and involved for a long time, I would need to have those other things to do,” he says.

After a while, the band started recording at Phillips’ studio. “It was a slow process until Luke [Steve Lukather] worked with me on a record I was producing and engineering, and he said to the other guys, ‘He’s got a great thing happening up there at his house, let’s record there.’ So, I had the whole of Toto in my house, I had a guitar rig in the garage and we recorded Through The Looking Glass.

“I got very involved but we kind of really broke up in 2008 after Mike [Porcaro] wasn’t able to play any more because of Lou Gehrig’s disease. Everything came to a head and we just needed a break. I think we’d needed a break for a long time and eventually Luke also said, ‘I can’t do this any more.’

“Then we got back together in 2010 and I was fine to do it if we only went out for a month a year, maybe a couple of times, two tours, but Luke really wanted to do more. So I said, ‘Okay, 21 years is enough. I need to do other musical ventures.’”

One highlight of Phillips’ work since 2010 has been his collaboration with piano phenomenon Hiromi and bassist Anthony Jackson in The Trio Project, but that group have been on indefinite hiatus since their July 2016 performance at The Jazz Café in London when Phillips was ill and Jackson suffered a stroke.

“Anthony and I were in a terrible state,” he says. “I was in so much pain; I was very sick. Anthony hadn’t been doing very well. He was slow. We had to be really careful with him, making sure he didn’t fall or slip coming out of the van, and sometime that night, he fell outside the Jazz Café and that was it. Then both of us were in wheelchairs in the airports, so Hiromi’s Trio consisted of Hiromi and [tour manager] Mario pushing two wheelchairs. So that was the end of that.”

Phillips was on the road to recovery after two months, but Jackson is still recuperating, so The Trio Project is on hold until he’s well enough to play and travel again. “It was probably time for us to take a break anyway,” says Phillips philosophically. “Too much of a good thing, sometimes people stop coming out to see you, but I’m sure we’ll do something again. I hope so.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 85 of Prog Magazine.