The dictionary definition of juju is: 1. an object venerated superstitiously and used as a fetish or amulet by tribal peoples of West Africa; 2. the magical power attributed to such an object; 3. a ban or interdiction effected by it. So a juju involves some sinister, scary goings-on, but there’s something compulsive and strangely sexy in its undertow. As Cole Porter might have phrased it: ‘Let me live beneath your spell/ Do do that voodoo that you do so well.’ The fourth Siouxsie And The Banshees album, released in June 1981, bewitched and bewildered the post-punk generation, proving the band to be much more than just punk-era chancers and establishing them as serious, transgressive artists with a unique voice and vision and a sound that entranced with style and subversion.

Juju reached number seven in the UK, staying on the album chart for more than four months. Its reputation has stayed strong. In the mid-90s. Melody Maker hailed it as “one of the most influential albums of all time”, while The Times, in 2004, described the band as “full of daring rhythmic and sonic experimentation… The Banshees stand proudly alongside PiL, Gang Of Four and The Fall as the most audacious and uncompromising musical adventurers of the post-punk era.”

As to whether it was the template for ‘goth’, Siouxsie Sioux has mused, “I’ve always thought that one of our greatest strengths was our ability to craft tension in music and subject matter. Juju had a strong identity, which the goth bands that came in our wake tried to mimic, but they simply ended up diluting it. They were using horror as the basis for stupid rock’n’roll pantomime. There was no sense of tension in their music.”

That the Banshees were ever a goth band was “simply not true”, said guitarist John McGeoch. “It simplifies things too much to give it a label like that. We were more thriller than horror movie, more Hitchcockian blood-dripping-on-a-daisy than putting fangs in something.”

The album is thrilling and tense. From the exhilarating opening salvo of Spellbound through the sweeping-stuttering drama of Monitor to the menacing Voodoo Dolly, it’s a work which fuses ugly unease and startling beauty like the films of, yes, Hitchcock, and also Luis Buñuel.

In Sounds in ’81, Betty Page’s review ran, “This is the soundtrack of the unknown, hinting darkly at black magic, witchery, murder and death.” It’s worth pointing out that the number one album when Juju was released – the summer of Charles and Di’s wedding - was medley-madness Stars On 45 by Starsound. OK, so Adam And The Ants’ Kings Of The Wild Frontier had been Number One for the entire spring, but this was still unorthodox, challenging stuff, wildly oppositional to the mainstream.

The Banshees were following up a relatively upbeat album, 1980’s Kaleidoscope. Despite its diversity (from synth-electronica to jagged minimalism), it made the top five, featured the hits Happy House and Christine and introduced new members John McGeoch and Budgie on guitars and drums respectively. The arrival of McGeoch (from Magazine) and Budgie (from The Slits) marked the dawn of what most consider to be the finest Banshees line-up. Now bedded in with Sioux and Steven Severin, McGeoch’s glancing guitars (since raved about by both Morrissey and Johnny Marr) and Budgie’s peripatetic patterns lent increased urgency to the band’s heightened sonics. Throughout Juju, the group are locked in to each other’s wavelengths, rising and falling together with sandpapery serration and deft dynamics.

If its predecessor had been studio-born, Juju consisted of songs honed in concert before recording. “We were still a young band,” Steven Severin told Mark Paytress for the 2006 remastered edition’s liner notes. “And we couldn’t wait to move on to the next thing. Most of 1980 had been spent regrouping, but 1981 was virtually non-stop live work. That certainly helped us get a wider audience.”

Siouxsie clones were turning up at shows in increasing numbers: a trend which jarred with Sioux’s ideas of individuality. The band took a month off to record Juju. Their credibility was at an all-time high, with success having found them despite their unwillingness to compromise. “If the album sounds unified, that’s because it was prepared that way,” said Severin. “It was rigorously rehearsed and played.”

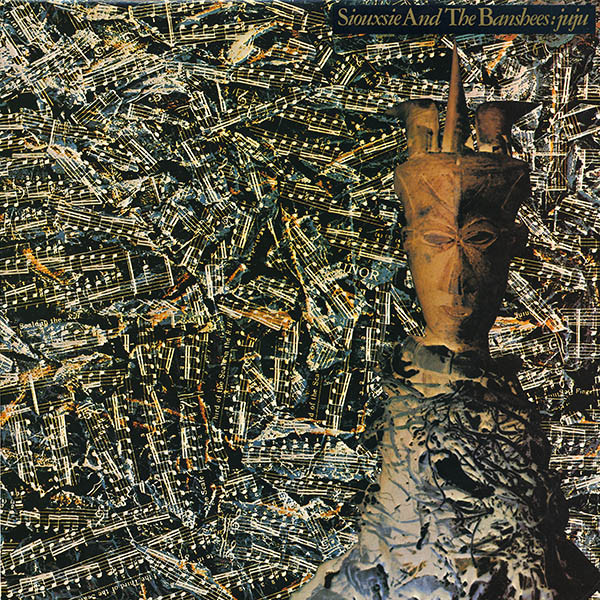

“It was the very opposite of the way we’d done Kaleidoscope,” said Sioux. Severin added, “It was the first time we’d made, for want of a better word, a ‘concept’ album. It drew on darker elements. It wasn’t pre-planned, but we saw a thread running through the songs… almost a narrative. The African statue on the cover, which we found in the Horniman Museum in Forest Hill, was the starting point for a lot of the imagery.”

Nigel Gray’s impeccable, crisp production did the rest. “We knew by then exactly what we were playing, and what overdubs we wanted to do,” said Severin. Sioux has commented, “It felt like a solid unified group around that time. A lot could be understood without anyone necessarily saying it.”

One thing that was articulated – between Severin and McGeoch – was a fondness for The Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request.

“We wanted that Stones/Small Faces-go-psych feel”, Severin said. The two singles – Spellbound and Arabian Knights – seem iconic now, but weren’t at all planned as hits. “They just came out like that.” The former carries another Hitchcock nod; the latter looks angrily at the oppression of women in the Middle East. Into The Light is prescient, off-centre white funk (with McGeoch aflame), while Halloween (okay, you can see how those ‘trick or treat’ references might get you labelled goth) is an adrenalised fever dream. Monitor is a poised yet relentless surge that deliriously keeps false-ending then coming back for more. An Orwellian tale of tower-block muggings, it has an acute, pulsing sense of paranoia. The chilling Night Shift (few could sing ‘fuck the mothers, kill the others’ as archly and ambivalently as Siouxsie) was inspired by the Yorkshire Ripper and Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir.

Sin In My Heart revs up then races breathlessly, but Head Cut is even more full-on, Sioux handling further macabre imagery (severed and shrunken heads) with indefatigable venom. And on finale Voodoo Dolly, which became a live set-closer, she’s possessed, a whirling dervish in the zone, demanding, receiving, ‘transfixing you to your fear…’.

“That’s the song which brought all the skulls and beads out,” Severin said.“But if Juju had a horror theme to it, it was psychological; nothing to do with ghosts and ghouls. We were quite confident with the image we were putting across, and were starting to play with it a bit.”

Indeed, the next album, November ’82’s A Kiss In The Dreamhouse, was more playful, flamboyant, even sexier, while again thoroughly intoxicating. McGeoch’s problems with stress and alcohol, though, saw him hospitalised soon after its release, with one Robert Smith called on to deputise: another story in itself. Juju is a night of a thousand stories, rich with nocturnal shivers and impassioned heat, a masterclass in fireworks, flying sparks and ice-cool hauteur from one of Britain’s most underrated bands. It sends you spinning. You have no choice.