Imperious, confrontational and bewitching, Siouxsie And The Banshees started out as the ultimate manifestation of punk’s DIY spirit, ultimately spearheading the movement into its subsequent post-punk phase.

Fearlessly experimental but boasting an uncanny pop sensibility, their 20-year reign would see them invent goth while regularly enlivening the charts with edgy, classic singles.

Perhaps the most imitated British female singer of all time, Siouxsie was the UK’s Debbie Harry, using success to fulfil unpredictable visions, confuse copyists and make a stand for strong women in the music business.

The massively influential records the Banshees released between 1978 and 1995 stand among the most timelessly evocative, provocative and compelling of their era, with songs tackling schizophrenia, childhood trauma, fatal compulsion, lacerated love and serial killers.

I accompanied many bands through this pivotal time. None of them matched the Banshees in the uncompromising, sometimes shocking single-mindedness of their mission.

For Susan Ballion of Chislehurst, the band marked the culmination of her escape from suburban normality. She had an isolated childhood, exacerbated by an alcoholic father and sexual assault at nine, her internal world fuelled by horror stories and older siblings’ Otis Redding records.

Transformed and validated when David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust album came along in 1972, Susan got her first taste of night life when accompanying her go-go dancer sister to work, flaunting provocative fetish images – self-described “armour” – as she found sanctuary in London’s underground gay clubs. She met like-minded misfit Steven Bailey from Bromley at a Roxy Music gig, and the pair started going to early Sex Pistols shows with fellow local malcontents, who were dubbed ‘the Bromley contingent’ by press.

While Suzie (as she was initially billed) introduced the Pistols crowd to multi-sexual Soho niterie Louise’s, her and Bailey (soon to be renamed Severin) embraced the scene around Malcolm McLaren’s SEX shop, stepping up to promoter Ron Watts when he needed a band to open for the Pistols and The Clash at his 100 Club punk festival.

The night before, she came up with the name Suzie And The Banshees as Severin picked up a bass for the first time. With (future Ants) guitarist Marco Pirroni, and their mate Sid Vicious on drums, they piled through The Lord’s Prayer, incorporating She Loves You, Twist And Shout, Deutschland Uber Alles and Knocking On Heaven’s Door for 20 minutes before getting bored and stopping. Soon after, Suzie ignited the Pistols’ outburst on Bill Grundy’s infamous TV debacle when fielding unwanted advances from the host.

Bringing in drummer Kenny Morris (who’d rehearsed with Sid’s Flowers Of Romance) and guitarist Pete Fenton, the Banshees began to explore brazen ideas and provocative lyrics, abusing rock’s traditions and embracing taboos, all the while admiring the simplicity of glam-rock.

Their next gig was supporting Johnny Thunders And The Heartbreakers for Watts at High Wycombe’s Nag’s Head in March 1977, during which they careered through Love In A Void and Make Up To Break Up, plus T.Rex’s 20th Century Boy and the Captain Scarlet TV theme tune.

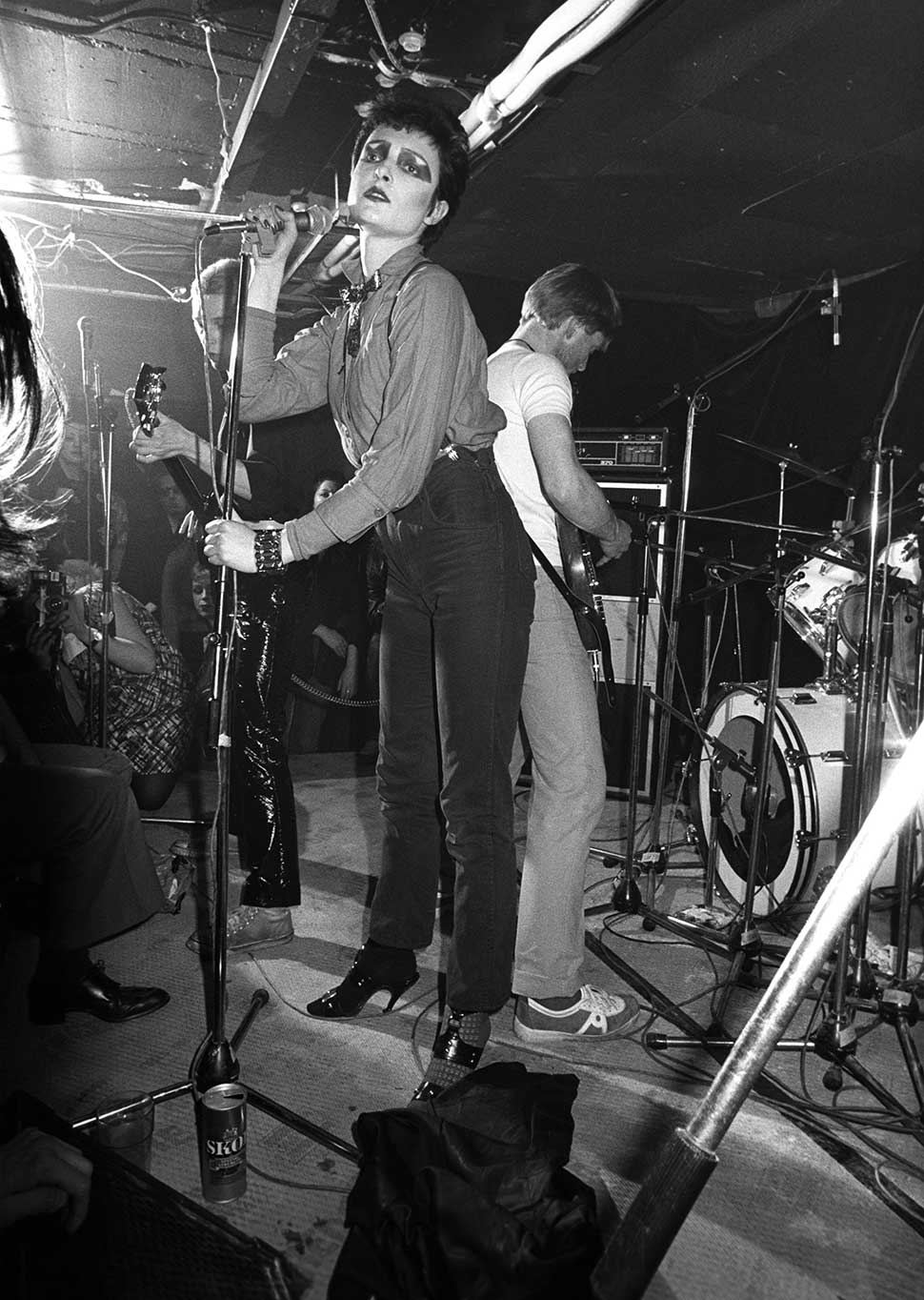

Strutting in stilettos like a pre-war Berlin cabaret madame, Suzie had become Siouxsie by the time they started playing London’s Roxy club later that month. Female punks relished having their own inspirational figurehead.

“We’re just not like everyone else,” Siouxsie declared when I put her on the cover of Zigzag magazine that October. “We just like to get people’s backs up. We’ve got a morbid sense of humour.” Later she stressed: “I don’t want to appear as some kind of Women’s Libber, cos I’m not, but neither am I someone who lets herself be pushed around and manipulated. I’ve got a mind of my own."

By the time they played the opening night of London’s Vortex club that July, co-headlining with the Slits, catalysed by John McKay replacing Fenton the Banshees’ punky attack had morphed into majestic, disturbing onslaughts like Suburban Relapse.

Crowned ‘The Ice Queen’, Siouxsie was gaining popularity and appearing on magazine front covers, but the Banshees couldn’t get a suitable record deal, receiving only insulting offers and rejections from A&R men. After their John Peel session in December became the most requested in the show’s history, the DJ even suggested releasing the Banshees on BBC Records. Fans sprayed ‘SIGN THE BANSHEES’ on record company doors, gigs sold out, and their self-promoted event at Alexandra Palace was well-attended.

Deciding that a Zigzag cover (designed by Severin) might help, my accompanying interview became a celebration when Polydor Records’ Chris Parry secured their signatures by promising them control over packaging, promotion and track choices. Meeting the band in Soho Square, an ebullient Sioux seemed almost shocked. I asked if she foresaw problems with Polydor marketing her as a UK Debbie Harry.

Yes!” she said. “Every record company we’ve come into contact with wanted to do that, but we were aware of it. That’s how we could stop it. It’s like a barrier. If it’s a girl, ‘Oh, she’s just flogging an image, she hasn’t got anything to say.’ They like that. Whereas if they think she’s got as much there as anyone else, and more so, they don’t like it. Everyone’s so conditioned to think men say this and girls follow behind or just look pretty. We don’t exist if we don’t have something to fight against.

“I can’t understand bands that are in love with the idea of being underground,” she continued. “If we got to Number One on Top Of The Pops it’d be a great achievement. It is starting and it’s what we’re striving for. If everybody starts liking us, then we’re going to find it very hard!”

Released in August 1978, Hong Kong Garden, with its infectious xylophone fanfare, reached No.7 as a glorious post-punk pop single. Its lyrics were inspired by a Chislehurst Chinese restaurant suffering racist skinhead attacks (‘harmful elements in the air’).

The Scream, produced by Steve Lillywhite, is one of the era’s great debut albums. Dark, dramatic and utterly new, it redefined traditional voice-guitar-bass-drums line-ups. McKay’s guitar sparked malevolent thunder clouds over Severin’s pulsing bass, while Sioux was a regal, animated presence on Jigsaw Feeling’s monolithic surge, the desolate Overground and Suburban Relapse’s harrowing, JG Ballard-influenced nightmare.

After they’d savaged The Beatles’ Helter Skelter, the epic Switch busted punk’s three-minute barrier as Sioux highlighted the grim consequences of a scientist, a doctor and a vicar swapping identities. Greeted with effervescent reviews, The Scream shot to No.12 in the UK album chart.

Two commanding singles later – the sinister waltz of The Staircase (Mystery) and the flanged-up onslaught of Playground Twist – second album Join Hands was underscored by the isolation that Sioux still felt occasionally.

The album took inspiration from World War One’s carnage for its memorial cover and ominous Poppy Day intro. The juggernaut grandeur of Regal Zone, Icon and a spine-freezing Premature Burial was offset by a softly disturbing Mother, which found Sioux singing sweetly over a music box playing Oh Mein Papa (before cataclysmic closer The Lord’s Prayer).

Join Hands tour warm-ups in Bournemouth and Friars Aylesbury were marked by the rift opening between Sioux-Severin and McKay-Morris that started at rehearsal. When Sioux, Severin and crew indulged their (little-reported) sense of humour, the other two tut-tutted like Victorian grumblers. Accompanying a sozzled McKay and Morris for a midnight stroll on Bournemouth beach, I listened to their discontent about fame’s pressures.

An ice curtain descended the next day when driving to Aylesbury in minder/ tour manager Mick Murphy’s customised van (along with crew members, they shared this gentle giant with Motorhead, the two bands enjoying a mutual respect).

Two days later, Morris and McKay flounced out of a record store signing in Aberdeen, never to be seen again. That night, at Aberdeen Music Hall, support band The Cure played a longer set before Sioux and Severin appeared to explain the situation. The Cure returned and played works-in-progress, joined by Sioux and Severin for a defiant The Lord’s Prayer.

Sioux and Severin seized the shake-up as a chance to move forward, nicking drummer Budgie from the Slits while Robert Smith played guitar with the Banshees after his Cure set. It sounded amazing even at rehearsal.

“Isn’t it great not to have a pair of old women moaning away in the corner?” a grinning Sioux said in the pub.

A rescheduled tour opening night in Leicester saw the rejuvenated Banshees driven by Dunkirk spirit and a bright new buzz, with Sioux strutting, skipping, dancing, working herself into a frenzy on Suburban Relapse. Drummer Budgie was a polyrhythmic powerhouse, while Smith weaved in ethereal subtleties.

Afterwards he said: “I was blown away by how powerful I felt playing that kind of music. It was so different to what we were doing with The Cure.” His Banshees experience catalysed his new look and The Cure’s next phase.

After auditioning vainly for a new guitarist, the Banshees enticed John McGeoch from Magazine. Completed with the newly rejigged line-up, their catchily insane single Happy House brought the Banshees a brilliant Top 20 return in March 1980.

While recording at Polydor’s studio, Sioux glowed with delight as she told me: “It’s given me and Steve a good kick up the arse to just do things. In the end we’ve got to thank John and Kenny for leaving. It’s turned out for the better that they left. I feel very jolly lately. It’s almost like starting again, which is how we wanted it.

"We’re all really excited by anything that’s unpredictable. Some sort of pressure, so you drive yourself rather than have someone to make you do something. It’s down to yourself to get out of your mess. The new album’s called Kaleidoscope because of the nature of the situation we’re in. It’s fragmented, but every fragment is strong, bright and positive.”

With Sioux writing on her new synthesiser and Severin his drum machine, new songs Christine and Eve White, Eve Black were inspired by The Three Faces Of Eve, a book (and subsequently a 1957 film) about Christine Sizemore, who hosted 22 different personalities. “They all had different names, which was a really good source for the lyrics,” Severin explained: “The Strawberry Girl, Banana-Split Lady, the Purple Lady, The Turtle Lady…”

The Banshees’ third album, Kaleidoscope, was their most commercially successful yet, beaming to No.5. It was followed by the atmospheric Israel, which welcomed the liberation of 12-inch singles.

The band weren’t about to stop there. After touring the US for the first time, they descended on co-producer Nigel Gray’s Surrey Sound studio to record Juju. For many, this is their best album.

May ’81 single Spellbound made an evocatively dynamic trailer, with blazing pyrotechnics from McGeoch and thunderous dynamics from Budgie. The album itself displayed Sioux and Severin’s creative muse on stunning form, with Arabian Knights, Voodoo Dolly and Nightshift (about a serial killer) imbued with cinematic depth.

Covering July’s Juju tour for Zigzag, I joined the merchandise stand crew and noticed the goth movement starting to emerge, with Siouxsie And The Banshees as reluctant figureheads. This could have been the band’s live peak, gloriously Gothic (in the original sense), raising the bar for mesmerising rock theatre. Drapes parted to reveal clouds moving behind four stark silhouettes on the custom-built perspex stage striking up Israel.

Different settings were used for each song: dusky moonlit evening for Arabian Knights; blood-red inferno for Sin In My Heart; lightning striking the stained glass window in Nightshift. Afterwards the band signed autographs while we sold T-shirts; worlds away from the aloof beings presented by the press.

Arising from sound-check jamming, Sioux and Budgie’s voice-drum duet But Not Them was a Juju outtake that swelled into their spin-off project The Creatures. They released the double-EP Wild Things, which included Mad-Eyed Screamer and their take on The Troggs’ 1966 classic Wild Thing. Meanwhile, Severin produced tour support Altered Images, including No.2 hit Happy Birthday.

Back in the Banshees’ camp, 1982’s singles Fireworks and Slowdive preceded the swamp visions and pyramids of fifth album A Kiss In The Dreamhouse, on which their love of psychedelic Beatles charged experiments such as having backwards strings on Circle.

At a sneak preview at Camden’s Playground studios, Sioux explained that the Dreamhouse was a 1930s Hollywood whorehouse, and Juju “like closing an era. That’s why we waited a long time before recording a new LP, so we could work out of that."

The changes taking place were compounded by a heavy-drinking McGeoch suffering a nervous breakdown and departing (he joined PiL, and died in his sleep in 2004). The Banshees decided to tour less and do solo projects. Severin played with Lydia Lunch and had a blast making psychedelic whoopee with Robert Smith as The Glove.

The Creatures replaced goth shackles with junglefever loincloths on their 1983 album Feast. That same year, with goth in full swing, the Banshees stood surveying their exotic children at the bar of Soho’s Batcave (where I DJ’d), laughing their heads off.

With Smith returning briefly, their baroque-psych version of The Beatles’ Dear Prudence reached No.3, and their triumphant gig at London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1983 gig was captured on their live record Nocturne.

The Banshees took such peaks as licence to experiment on their hallucinogenic album Hyaena, notable for (among other things) the Camden Palace dancefloor-friendly gallop of Dazzle.

Orchestral arrangements of old Banshees songs were captured on The Thorn EP, introducing new guitarist John Carruthers, previously with Clock DVA (after he passed his initiation playing a gig at a lunatic asylum in Milan), along with keyboard player/ cellist Martin McCarrick.

When the Banshees toured in autumn 1985 (while recording seventh album Tinderbox), Sioux’s leg was in plaster after she cracked her knee at their Hammersmith Odeon show.

At the show I saw at Nottingham’s Royal Concert Hall, she might have been perched on a stool, but she still berated crowd-bashing bouncers before Severin dropped his bass and steamed in. In typical fashion, the fracas ignited a killer set, the Banshees powering like a juggernaut dervish, although Sioux maintained she’d been “trying to break glass with my voice rather than break heads with my mic stand”.

New song Candy Man was one of the blackest in their black catalogue, emotionally sung from experience by Sioux, who told me it was “against the perpetrators of incest or child-molesting, using a sickly-sweet person as the theme”.

Sioux and Severin were almost 10-year veterans by then, and still refusing to sell their souls or become self-parodies.

“We’re lucky we’re not so big that we’re untouchable,” said Severin. “It still matters that when we go on stage we have to be good and live up to our reputation. We’ve never slogged up and down the motorway for no reason other than to get famous. We’ve had an advantage in a way, because we’re so arrogant and stroppy about what we do it keeps us sane.

"We still have interest and time to breathe around everything. That’s the only way you can carry on and still be good. A big reason we’ve kept going is because it hasn’t been the same format and personnel. We’re nine years old and I don’t think we’re crap."

“All mistakes somehow seem swayed in our favour, mishaps or bad luck turned to our advantage,” added Sioux. “That’s all; you cannot bemoan it or feel sorry for yourself. I think being really good friends is important. So many groups hate each other, don’t socialise or even work well together. It’s no way to live your life, really.”

After covers album Through The Looking Glass, 1988’s Peepshow introduced Specimen guitarist Jon Klein, before Sioux and Budgie took another Creatures detour with 1989’s Boomerang (Jeff Buckley later covered the song Killing Time). They also got married and relocated to south-west France.

The Banshees returned with 1991’s Superstition, with producer Stephen Hague stoking Sioux’s disdain for studio computers. 1995’s The Rapture, part-produced by John Cale, became the Banshees’ swansong.

In 1984, asked if he would know when it was time to finish the Banshees, Severin told Zigzag: “I hope so, and I believe we would know. The understanding between Sioux and I wouldn’t allow us to carry on if that feeling wasn’t there. It’s instinctive and I trust it.”

That moment came in 1996, as nostalgia raged for punk’s twentieth anniversary with a Sex Pistols reunion. Sioux stated: “I just think it’s the most dignified thing to do for the idea of the band and the spirit in which it started. We’ve had a fantastic journey.”

Siouxsie and Budgie continued as the Creatures before splitting around 2004. Siouxs’s next release was 2007’s Mantaray, her robustly diverse solo debut. Her last recorded statement was 2015’s haunting Love Crime, for the Hannibal TV series finale.

Operating at a lower level, Severin composed film and TV soundtracks, released instrumental albums and played solo in front of silent films. The last time I saw them I was DJing for Metallica at London dance club Ministry Of Sound in 1997. The Banshees now gone, we laughed at that journey we’d been on after that 20-minute set became a 20-year career.

They reunited once, a core trio joined by guitarist Knox Chandler, for 2002’s Seven Year Itch tour, from which came the following year’s live album of the same name. The set-list for the tour favoured early album tracks rather than their greatest hits, typifying a band whose influence had burned into rock’s fabric.

Today, Siouxsie’s image and statements are evident in many a female singer speaking their mind and following their own path. Siouxsie And The Banshees saved punk from parody, scored transcendent hit records, invented goth and still went out with rare dignity.

One of a kind, once upon a time.