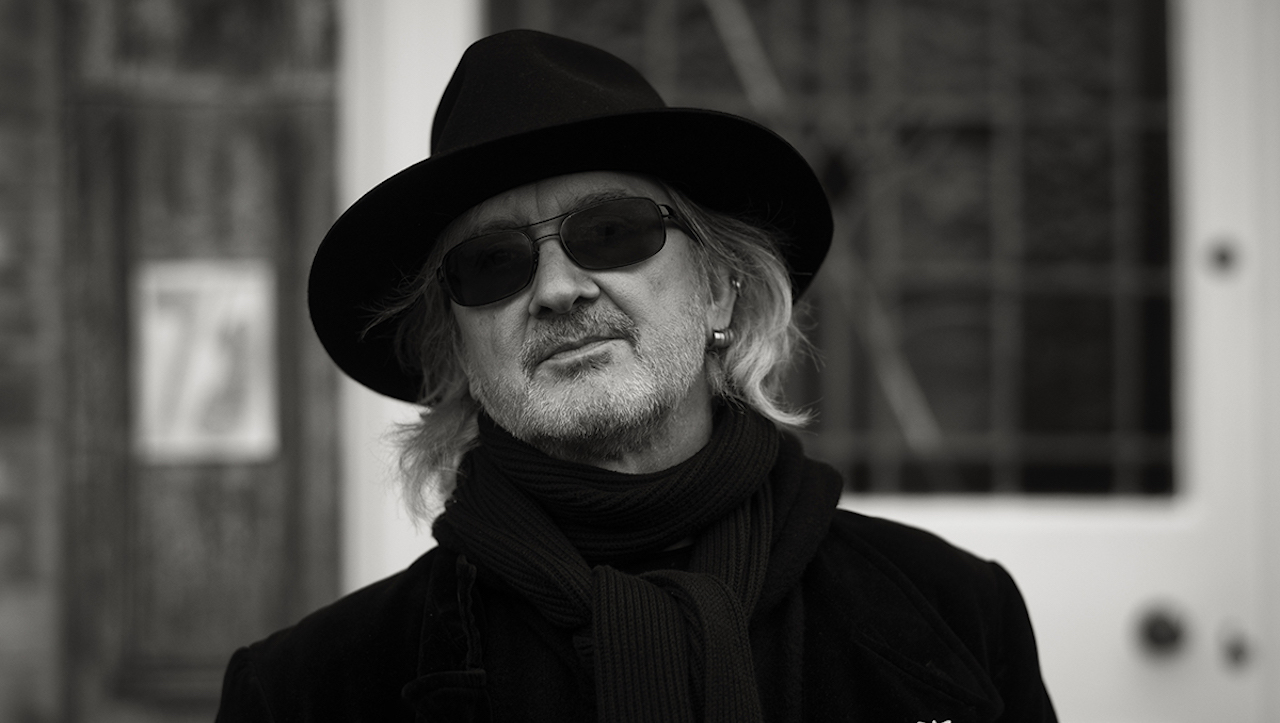

Hairspray tips from Alan Vega; a sadist in Plymouth who leaves him needing to wear sanitary pads, getting his head puked on before his first ever American gig – Wayne Hussey’s autobiography has plenty of rock’n’roll weirdness and Excess All Areas shenanigans.

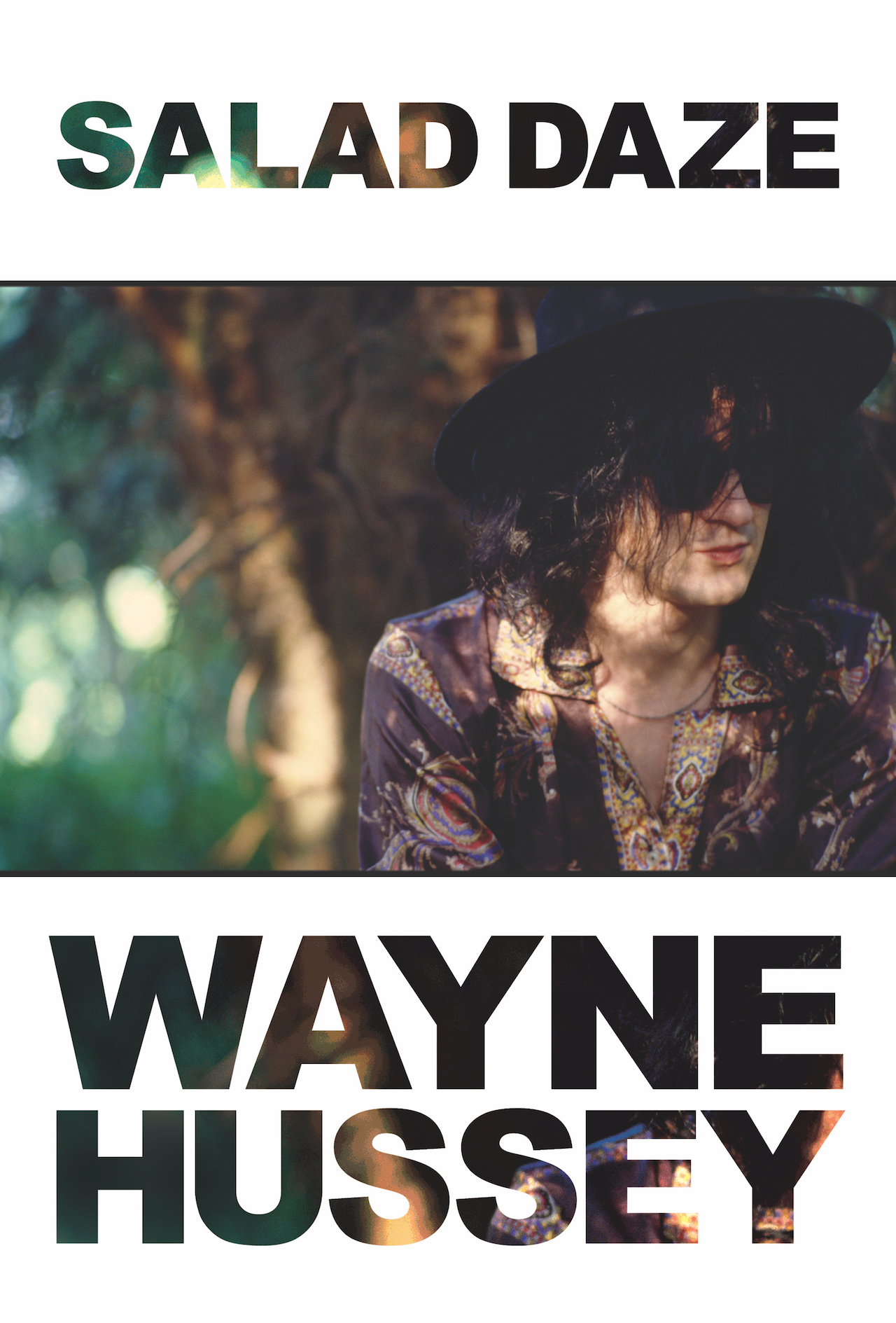

Beneath that crust of debauchery – and it’s a thick crust of powder and fluid at times – the narrative is one of perseverance in the face of repeated failure. Salad Days is a story of a struggling, driven musician, repeatedly thwarted on what he expects is his path to glory.

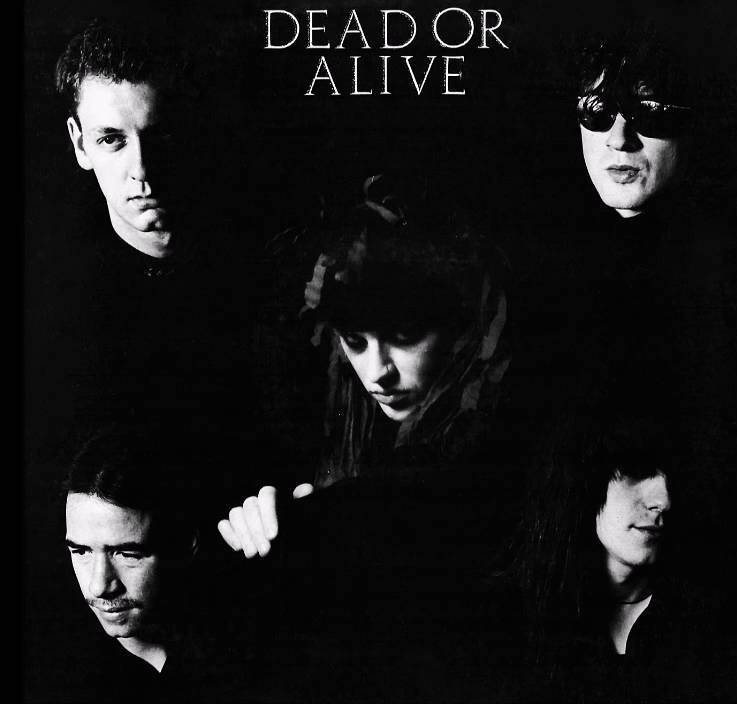

In Salad Daze, one band after another doesn’t work out for Hussey: The Ded Byrds (also known as The Walkie Talkies), The Invisible Girls backing up Pauline Murray, Hambi and The Dance, Dead Or Alive and finally The Sisters of Mercy. Each one is link in a chain that led to eventual success and fame in The Mission. Yet The Mission are not in this book. Salad Daze takes Hussey from his birth in Bristol in 1958 to walking out of a rehearsal studio in Leeds – and The Sisters – in 1985.

Salad Daze is, in effect, composed of three parts:

Lastly – and longest – is his time in Leeds and in The Sisters, touring, making First And Last And Always and failing to make its follow-up.

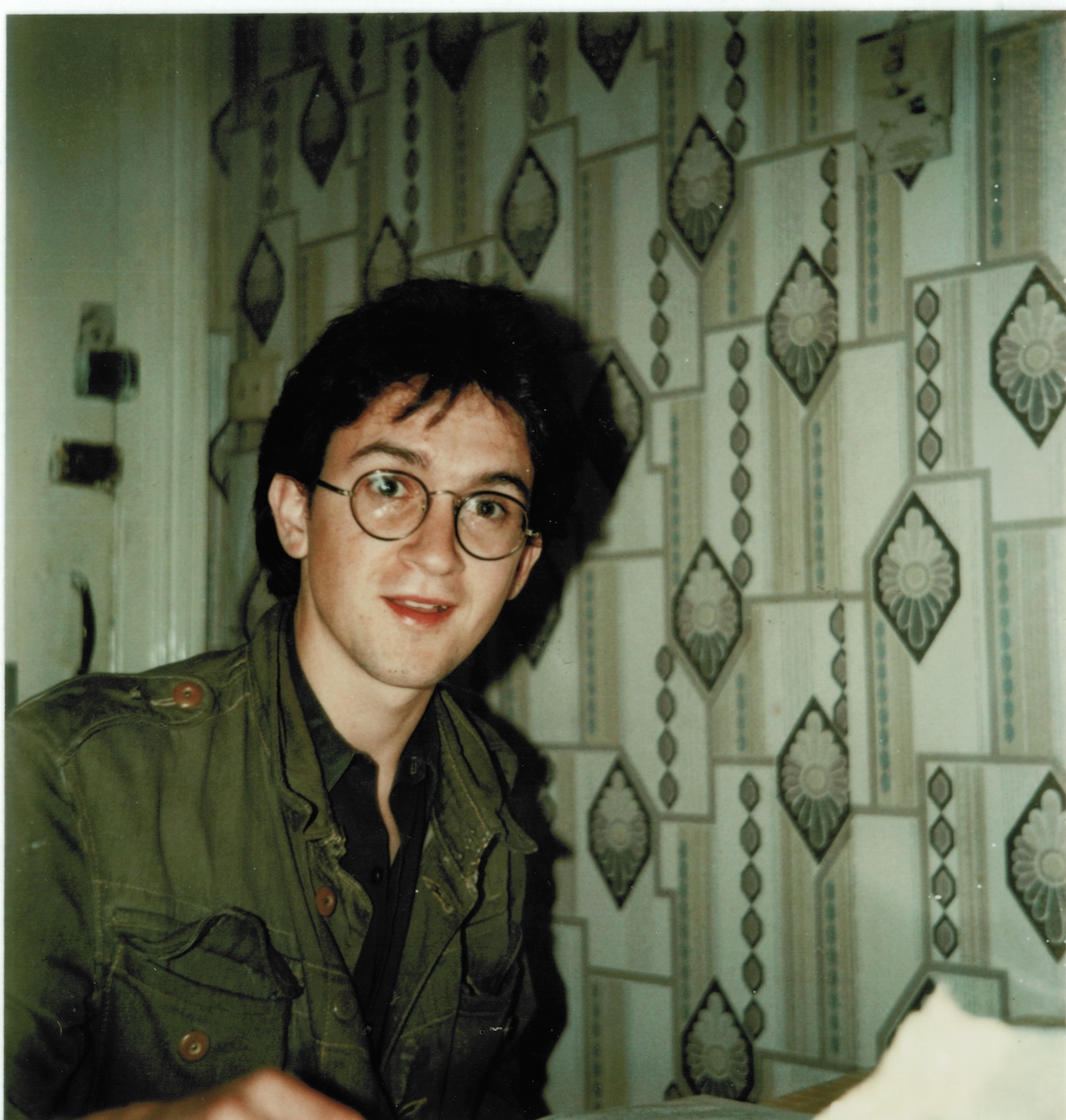

The middle section covers Hussey’s period in Liverpool, during which he became part of the scene centred around Eric’s and was inducted into “the dark arts.”

The first section is his childhood in the Bristol area: his school days, his first bands and his Mormon upbringing. The Preface claims Salad Daze is a tale of “moral ruin”, since the book is replete with evidence that Hussey has denied himself entry into Kingdom of Heaven.

The first section on his youth was the hardest for Hussey to write. In fact, he wrote the first chapter last, and only after consulting with his parents, since he has never discussed the details of his background in public before.

Hussey is convinced this first chapter is key to understanding much of what follows.

You decided to write openly about your family history for the first time – why?

My parents have not wanted it well known. I’ve not brought it up in interviews ever out of respect for them. But when I had almost finished writing the book, I thought, “You know, a lot of who I am and what I became and the way I’ve lived my life is probably a lot to do with my very early life.” I went to my mum and dad and asked them, “Would you mind, if I put this in the book?” They talked about it and said, “You know what, we’re 80 years old now, it’s fine.”

So I interviewed my Mum; I’ll always have the recording of that.

When I was about 10 or 11, I was at church one night playing a board game with the secretary of the church branch and he said to me, “So when did your parents tell you, you were adopted?” “What?!” I was in tears. I had no idea. My parents came down to the church: “Wayne, we never kept that a secret from you. You remember don’t you, the wedding? Your dad adopted you.” They didn’t keep it a secret, but at the age of four you don’t retain many memories.

But it was only then that I found out that my dad wasn’t my real dad, but I do have a hazy memory of there not being any men in my life when I was very young kid.

Did you ever try to get in contact with you birth father?

No, my dad’s my dad. He’s always been my dad. It was one Easter about 5 years ago when my parents were over in Brazil – they had the property next door to where I live in the countryside. “Easter Friday,” my mum said. “That’s the day I told your Nanny Lovelock; it was the day she received a letter from me telling her I was pregnant.”

And that’s when she told me stuff she hadn’t told me before; she told me my father’s name, that he was from L.A., that he had been in the services in England, that he never knew she was pregnant and that he had a son. I looked him up online – I didn’t want to track him down or meet him – and as far as I can ascertain he died in 1991, so I wouldn’t have been able to get in touch with him anyway. I’ve never really had that curiosity, other then when my second daughter was born and my wife at the time was asking me about it.

The early part of the book is also full of things that only a person of a certain age can fully appreciate: top-flight footballers who have fish fingers for dinner; corporal punishment in schools, Ron Ely as Tarzan, the subtle class divisions between Pontin’s and Butlin’s. The social history is interesting.

I’m not going to write a book geared towards an age group that don’t know who I am and I like reading about historical context in other books. It’s quite a memory-provoker in itself. I let Tim Palmer (producer of several Mission albums) read the book and he was messaging me every day: “I remember Stingray” or whatever.

Also the more sinister social history is in there too: TB and Mother and Baby Homes, for example. Are you still nostalgic about your deeply British, 1960s childhood?

I look back, and despite the circumstances of my birth, I think of my childhood as being a really pleasant time. I don’t think it’s left me with any great traumas or problems later in life, like it seems to do for other people. I’m lucky in that respect.

Would you describe your upbringing as working class and poor, but not deprived. Real butter is a treat in Salad Daze and you had to wear extra clothes rather than your parents putting the heating on during the bitterly cold long winter of 1962/3.

We weren’t comfortable, but I wouldn’t say deprived. I had a bike. We had a sledge and a go-cart that dad made. They couldn’t afford a Fender Telecaster, but they got me an Audition guitar from Woolworth’s. No, I never felt deprived at all. There was a lot of support and love – and there still is in the family.

There’s always a black sheep in large families - in your case, your Welsh granddad.

I only met him once or twice before he died. In fact, I’ve tried to be the Black Sheep myself, although I’ve got a cousin who’s been in and out of prison a few times. I saw him a few years ago at a wedding: “I haven’t seen you in a while,” I said. “Yeah, I’ve been away.” Where’ve you been?” “Pucklechurch.” It’s a prison in Bristol.

There is wild speculation in the book that JK Rowling based Harry Potter on you.

When JK Rowling became famous, it became known that she went to the same Junior School as me. She was the most famous ex-pupil; I am on the list as well. Our Headmaster was supposedly the inspiration for Albus Dumbledore. I’ve got my own stories about Mr Dunn. He caned me when I was about 5 years old.

When I started wearing glasses it was the time when she would have been in the school – she’s 3 or 4 years younger than me. Getting glasses was a huge traumatic experience for me. These days, kids don’t think twice about it; my niece goes to school with frames with no glass in. Back then I was the only kid in school I can remember having to wear glasses. So it did cross my mind: I wonder where the visual inspiration for this character came from? It would be nice to know; put that theory to bed. I knew nothing about the Harry Potter books, but I thought I’ll put two and two together and make another number.

Anyway, I heard JK Rowling liked Goth music when she was younger.

It sounds like wearing glasses was a worse trauma than being caned?

Yes. That was the biggest trauma I’ve carried into adulthood. At that age, all I wanted to do was be part of the gang. I didn’t want to stand out. When we started going to church that was one thing that made me different, but the glasses … I remember being called names and crying my eyes out.

My other nan - Nanny Hussey - worked in the kitchens in school, and I went in crying to her. She came out chasing the kids around the playground: “Don’t you call my grandson ‘Four-Eyes’”. Of course, that egged them on even more.

I remember why I got caned. Round the back of the school we had a coal shed. I was in there with Leonard Anstey, who was a naughty boy and we started throwing the coal around and it went all over the place. Mr Dunn took us into his office and caned us. On the ass. Really hard. It was the only time I got caned at that school. I got caned again in the High School though.

Mormonism seems to have been a mixed blessing: intense sexual guilt but also an extended family and support network in your early life. When you reflect, how do you think of The Church’s role in your life?

Positively, I have to say. There was a lot of emphasis on the family and the social aspect of The Church. It wasn’t just church on Sunday, there were different activities throughout the week. That, outside of school, was my prime social life. The memories are good. It was only later when I started questioning The Church as a teenager, when I was in situations that The Church advised you not to get into. That’s when I started feeling guilty.

That residual guilt that you end up carrying – it’s not exclusive to Mormonism – that can be crippling, but I was fortunate to be able to work my way through that. It wasn’t really until my 40s that I started to feel healthy in my attitudes to sex. There was a lot practice. Until then I thought of sex as separate to a relationship.

So there is just unhealthy sex in this book?

If you want to be analytical about it, putting that first chapter in also betrays the fact that I was spoilt by girls – women who were teenage girls, basically – from a very early age. I didn’t have a male influence until I was 4 years old. I think that coloured my attitude to relationships for a long time.

You were in The Scouts with Jon Klein, later of Specimen and founder of the Batcave. He was also a Mormon. What a bizarre co-incidence of Goth icons?

We get everywhere. And I only found out during the writing of this book, that [Bowie guitarist] Mick Ronson was also a Mormon. He was buried in a Mormon chapel. And he shared the same birthday as me.

You’ve seen the positives of The Church for your parents. Do you miss that kind of religious faith and certainty.

I like to think they will be off to the Celestial Kingdom. When we discuss religion, we don’t see eye to eye, but I am interested in their viewpoint. They have intelligence but believe in things, which to my mind are totally irrational, but I am envious of their surety, their certainty.

The first ‘stars’ you encountered seemed to be the Mormon prophet, Marc Bolan and Ray Graydon of Bristol Rovers and Aston Villa. Is that the correct impression from the book?

Ray Graydon, for sure. I was a football-mad kid. He was one of my favourite players. The prophet was the head of the Mormon Church: you can’t get any closer to God than the prophet. And Marc Bolan – definitely. I’m actually going to L.A. in July to film a video with Rolan Bolan. I did a vocal and played some guitar on a new version of 20th Century Boy that he’s singing.

Your first instruments were drums and piano, but they just didn’t capture your interest the way the guitar did. Why?

Just timing. The drum kit was bought when I was 6 or 7. I was too young and I got sick when playing it. A bit like eating too many Bountys as a kid. I’ve never been able to eat coconut since. I really wish I had pursued the piano but my teacher was a nightmare. She rapped me across the knuckles with a ruler and it was a scary place where she lived: a dark house with all this taxidermy. Plus they try to teach you stuff, you weren’t interested in. I wanted to play Beatles songs, not have to learn my scales.

The most sensual description in the book is of a black Fender Telecaster, rather than any of the sex in the book.

The episodes of sex that I write about in the book are supposed to be funny rather than sensuous. Guitars to me are sexual, the way you play a guitar – you hold it close to your body, you caress it, whereas when you play piano you are actually pushing away. There’s some psychology in playing an instrument.

Other rock bios have led you to conclude: “the path they follow in life is determined by … a dysfunctional family.” Not true of you, but who do you think this applies to?

When I read about other rock starts they seem to be motivated by having this point to prove to the world and having to deal with abuse of one kind or another when they were kids. But I do feel really normal; I’m not fucked up like some rock stars you read about in books. I have a good life, I’m reasonably well balanced. It’s been difficult for me to empathise with those who have something to vent against.

In life, you gravitate toward people you have something in common with, you get on best with people who understand your points of reference: normal loving families, brought up away from city centres. All the members of The Mission – Mick (Brown), Craig (Adams), Simon (Hinkler), even Mike (Kelly) now – the parents always came to the gigs and from Day One were very supportive. We even got them down to the studio a couple of times and we had to share one bedroom and give the parents our own personal bedrooms.

My parents came to see The Sisters when we played in Bristol at Trinity Hall down in the Old Market. They didn’t really like The Sisters very much.

You had a series of school bands but after that you joined other people’s bands. This book is really your “Sideman Years”, but there is a sense of you chafing against that.

I have always been driven. Whatever band I’ve been in, I’ve wanted to be very involved and, in a lot of cases, have carried that band. But that’s another reason why I wanted to put that first chapter in. That whole episode – how I came to be, that I was supposed to be taken away for adoption – that has informed an awful lot of the character I became. That was a subconscious factor in my drive. I’m sure some psychoanalyst could argue differently, but it makes sense to me.

Salad Daze is also a story of repeated failure, the dashing of expected success time and time again. You were in bands that got deals and made records, but didn’t become successful: The Ded Byrds signed to Sire; Dead Or Alive to CBS…

And I left Hambi and the Dance just before he signed a big record deal. Pauline Murray, there’s another one: “This is going to be my stepping stone to fame and glory” but no, it didn’t happen. That became normal for me. What this proves is my adaptability and maybe even a chameleon-like ability to adapt to whomever I was playing with at a point in time.

Do you worry that makes you sound like an opportunist?

Actually, I agree with that to an extent. I was unashamedly ambitious. I was an opportunist in the sense that I would move from band to band but I would also contend that there are lots of brilliant guitarists in the world but there are very few that actually have their own style, their own sound. There are millions of guitarists than can play far better than me, but when you hear how I play guitar, the way I pick out melodies or arpeggios – it’s the Wayne Hussey style, which has evolved over the years and you can hear traces of that in the early demos. I’m obviously privy to a lot more music than is out there, so I can hear the evolution of that style.

I think I was lucky that when I started, rather than trying to play other people’s songs, I started writing my own because I found it easier to do so. If I’d have sat there for hours trying to work out other people’s guitar lines I might not have developed my own style in such a special way.

Someone like Mark Gemini Thwaite (guitarist in The Mission in the 1990s) is a far better technical guitarist than me. “I kind of hear this like Radiohead” and he’ll play it like Radiohead. “I kind of hear this like The Cure” and he’ll play it like The Cure, but he doesn’t have a discernible style of his own.

In The Sisters, Mark (Pearman aka. Gary Marx) maybe wasn’t the best guitarist but he came up with some great guitar lines. Mark’s tunes on First And Last And Always are great. I like the stuff I did, but – apart from Marian – the stuff Mark did has weathered better for me personally.

David Knopov of The Ded Byrds was the first of the sequence of rock stars and would-be rock stars you played with. The only fight in Salad Daze is between you and him: Ian Broudie pulled you apart outside the Armadillo Tea Rooms on Mathew St in Liverpool. Surely there were punch-ups in other bands?

No, it never got physically violent with Dead Or Alive. I can’t remember much tension at all until I came to feel a bit redundant as a guitar player. We got involved in a fight once coming out of a gay club. Pete Burns had gone out before me and when I came out of the club I saw him being dragged up the street by his dreadlocks by a group of lads, so I chased after them. Then the other lads from Dead Or Alive came out and we all had a fight in the street. But that was us fighting them, not us fighting each other.

In The Sisters we argued a lot, but it never got physical, which is extraordinary knowing Craig. Craig’s had a few goes at me over the years in The Mission. I remember one time we were flying to Australia and I was heavily into a drug called Ice at the time and I was in my own world. At the time, me and Craig basically weren’t talking. Mick was sitting next to Craig and I was on the other side of the plane listening to music with a Walkman on and reading a book.

Mick said to Craig, “Wayne’s fine: all you’ve got to do is talk to him.” Craig had been drinking the free booze on the plane. He came over and I just looked up and saw him ranting and then he just punched me in the face on the plane. The crew guys wrestled him to the ground and then took him to the back of plane and tied him down. That was his idea of “Yeah, all you’ve got to do is talk to Wayne.”

Craig’s resorted to violence several times. He reaches this point: he’s a great drunk up to a point and then he’s a fucking nightmare. I still love him but I recognise the point when it’s time to leave the room.

You’ve not had that many ‘real’ jobs. The book mentions being a clerk, a management trainee in a Co-Op, loading Russell Hobb kettles into cages, dunking rubber into detergent and working in a music shop. Is that it?

Yes, I’ve not had what you would call a normal job since 1978.

Has music ever gone so badly, you’ve nearly had to get a job-type-job?

Oh yeah. Definitely. I remember in the early 90s when The Mission lost momentum and we were playing to smaller audiences, not getting in the charts any more and we got dropped by the record label at the same time my second daughter was born, so I had to sign on. It was a horrible, horrible time. Also at that point the band had heavy, heavy debts. If I packed in the band I would have been liable for the debt, I would have had to declare bankruptcy, so I carried on with the band and worked off those debts over the course of the next couple of years or so. When the debts were cleared I split the band and moved to California.

So, yeah, there have definitely been times when I’ve thought, “This ain’t working and I’m not happy where I am” but I’ve not really known what else to do. When I moved to California, I wanted to get into film music, so I pursued that but the problem there was that I wasn’t really cut out for going to the parties and schmoozing, the meet-and-greet crap. Besides music, I don’t know what else I could have done. I didn’t start driving till my mid-30s; I couldn’t have been a taxi driver. Music is what I can do and what I’m good at.

The Eric’s scene in Liverpool incubated an extraordinary number of famous musicians: Holly Johnson, Pete Wylie, Julian Cope, Ian Broudie, Ian McCulloch, Bill Drummond, Budgie, Pete Burns and others. How do you explain that?

It was different to Manchester: The Pistols did play Liverpool but apparently – it was before my time – all these people who became big in the Liverpool scene went to see them, but they were rubbish that night. They didn’t have the same impact as they had in Manchester. A band that did influence the Liverpool scene was Deaf School – they never got the national acclaim they should have – but in Liverpool they were very popular. It was more The Clash’s White Riot tour in May 1977 that the Liverpool scene germinated from. All these people started congregating in Eric’s. They were all there when I first started going.

It was very fertile but there were also these people who didn’t become famous: Knopov and Hambi were two people who were odds on to be pop stars but it didn’t happen for them. And there were other people like that: Jayne Casey, she was the singer in Big In Japan. Everyone else in Big In Japan went on to further success, Jayne didn’t, although she’s had her own type of success: she got into dance clubs, like Cream.

You were incredibly gauche when you moved to Liverpool: a bean bag in Pauline Murray’s flat was a sign of Bohemianism

Very sophisticated that. And nice posters on the wall. And heating.

It was a steep curve from there: You went from taking up smoking on your first tour – duty-free cigarettes on a Scandinavian ferry - to a few weeks later, Martin Hannett teaching you how to snort coke.

That is how it happened.

Pete Burns sounds quite brutal company in the book.

He could be. Gay people can be really bitchy. But very funny with it. Pete was hysterical. A lot of his humour was borne out of that bitchiness. He was a real diva – way before he was famous. It wasn’t a personality trait he developed when success came, he was always like that.

Yet, by the end of the book Andrew Eldritch seems to have gotten under your skin more. Both him and Pete Burns could be verbally very cutting.

Pete was a bitch and he was a gay bitch. Andrew was not a gay bitch. Andrew – there was no warmth in him. Pete, no matter what, could be really, really warm and loyal and I felt he had an awful lot of respect for me, for what I brought to him, to Dead Or Alive, whereas I never felt that with Andrew. I never felt he really respected me or valued my input. We need some kind of validation in what we do and I never got that from Eldritch. He got under my skin a lot more than he deserved to, to be honest.

Your relationship with Eldritch seemed to often revolve around him as an authority figure. You refer to him as “the powers that be.”

Andrew was managing the band. It’s not like he came and conferred with us. We had no say. Although I do remember him asking me about Dave Allen (producer of First And Last And Always) because I’d worked with him before but Andrew really wasn’t one who asked for opinions. He was quite self-contained, which is a strong attribute to have. I wish I could be more like that.

Touring in The Sisters seems to have some of the dynamic of a school trip: you and Craig - “The Evil Children” – in the back seat of the bus, annoying the teacher – Andrew – in the front.

Eldritch would reprimand you and tut at your behaviour. Being in a band is funny and we saw the funny side, but he would tut at us for pissing in the beer or having blow-up doll for an interview with a sex channel. Obviously Andrew had a sense of humour, but his humour was probably more public school boy.

The Hussey Diet in this period was a gram of speed, a loaf of bread and some oranges to last a week. Plus a load of alcohol. How come only Andrew got ill?

Because I wasn’t as stressed out as Andrew became. Andrew was carrying an awful lot of responsibility. A lot of that was because of his inability to delegate. Before First And Last And Always he’d spent the last year negotiating the deal, setting up the publishing, the label, the office, and hadn’t had time to write any songs. That is part of the reason he has such a downer on First And Last And Always because his actual contribution to it is not as it was with other Sisters’ work. None of us were living a healthy lifestyle but Craig and I did go outside now and again, we did get some fresh air.

You know what Eldritch is like with lyrics: it can take him six months to write a single song. He had to write an album’s worth of lyrics. That pressure might have been self-induced but it was immense.

Making First And Last And Always sounds like an horrendous experience.

Originally we went into Strawberry (Studios in Stockport) to finish the album, but it became evident early on that we weren’t going to. We had a lot of the tunes worked out and demoed, so it was just a case of recording what we demoed. There were a couple of additions – Marian being one of them.

We ended up working 24 hours: Andrew preferred to work at night, so poor old Dave Allen had to work part of the day and part of the night. The idea was that Andrew would work on vocals at night but he would procrastinate working on drum reverb: you don’t do that until it’s time to mix. It was obviously a ploy.

I get it now. Many years later, I get it. To sit down and write a lyric you have to be in the right frame of mind. There has to be a kick, to kick start it. So you busy yourself with things of less importance because you don’t want to have to face it at that point.

Getting crabs on The Sisters’ Black October Tour is probably the funniest story in the book.

Craig and I got crabs on tour. We’re not sure where or how: I contend I got them from him, he contends he got them from me. We shall never know. Our sound guy, his wife was a nurse and she told him, “Tell them to put this ointment on every day on the hairy parts of their bodies and to wear shower-caps.” So we sat on the tour bus – The Flying Turd – in our underpants with shower-caps on our heads. It was a few weeks later when he admitted he made up the bit about shower-caps, just to let the crew have a laugh when me and Craig would turn up for soundcheck.

And Andrew refused to ride in the van.

Of course, I dare say I would have done as well. But I think it was any excuse.

In retrospect, do you have any sense that you stabbed Gary Marx in the back? It was you who made the phone call firing him from The Sisters of Mercy.

In a lot of people’s minds, I’ve got the blame for the split up of that line-up, but it wasn’t my fault. I was just the messenger boy. This was just after we’d done Whistle Test. Mark went home and the three of us stayed in a hotel in London and that’s when Eldritch issued the ultimatum.

I came up with this hypothesis in the book that the problem between Mark and Andrew was that by the time I joined the group, Andrew had become “Eldritch”, whereas Mark knew him when he was Andy Taylor. I only caught rare glimpses of “Taylor”, most of the time it was “Eldritch”, that persona. I think Andrew resented the fact that Mark could see through that charade, that pretentiousness, if you want. Having to live with that constant pressure of being someone with a contrived persona has got to be fucking hard work.

Rather than doing Eldritch’s bidding and firing Mark, shouldn’t you and Craig just have quit too?

We could have done but we had a big European tour coming up and a big American tour. I guess there was self-interest there: why leave something that was a going concern to start from scratch again. Although, we did do it six months later anyway.

During this period of The Sisters of Mercy, the band was clearly just an alliance of convenience.

I think it already was when I joined. Mark and Andrew very rarely spoke, even though they lived in the same house. Originally, they had been more like partners but it had been a case of Andrew wresting control, or Mark relinquishing control. I think Craig would have a lot greater insight than me because he was there from the beginning and saw how those relationships evolved. The dynamic I came into was not the dynamic he came into.

The Sisters sound wasn’t changed by me; they wanted to change, they wanted commercial success. They brought the snap and crackle, I brought the pop.

There is a lot of positivity from Sisters fans towards you and the book, but you are well aware of “certain factions” that are “bigoted and sour.” In one of the online forums, one person has commented that they would “rather get their asshole waxed” than buy your book.

There is that cabal, that coven out there, those witches who don’t like me. Fuck ‘em.

You met two rock legends - three if we include Ian Astbury - the night before The Sisters’ legendary Albert Hall show and got very different receptions.

Ian called me and said, “Do you want to go out and see Killing Joke? I’m going to bring a friend.” I naturally assumed it was going to be a female friend, a girlfriend. Lo and behold, it was Lemmy. Lemmy was instantly, “Here, have some of this”: got the wrap out, put some speed on a blade and put it under my nose. He had a bottle of brandy he was passing around.

And then we got to the Hammersmith Palais. Lemmy swanned in: “These are my mates.” He didn’t even need to say he was on the guest-list, he just walked in. I followed him in and he walked up to the bar. While he was talking to somebody at the bar he pulled me into the conversation: “Wayne, meet Jimmy.” It was Jimmy Page. He was off his tits. He was really out of it, slumped against the bar with a girl on each arm. They were holding him up really. At that point I was almost obsessed with Jimmy Page. The first thing I could say was, “Will you produce our album? “Fuck off.” “Alright, then.”

That was the extent of the conversation. Obviously, not the best time to ask him. The next day we played the Albert Hall and I had the most horrific hangover, which Eldritch was not happy about.

When the three-piece band was in America for the last time, you’ve written that having a “urethra swab” would have been preferential to socialising together. After filming the Black Planet video, Andrew went to Tijuana, you and Craig went to Disneyland.

We had the keys for the hire van while Eldritch swanned off to Tijuana, so we thought, “Right, let’s go to Disneyland. That sounds like a decent way to spend a day.” Craig hadn’t driven for about five or six years; he couldn’t change gear. Or work out how to turn the lights on. When it got dark, he had to get out and ask the bloke in the car in front, “Can you help us turn our lights on, please?” Although, we nearly did end up in Tijuana. We got nearly as far as San Diego before we realised we had missed the turning for Disneyland and gone too far.

You had two near death experiences in New York: running red lights in Manhattan while tripping with a man called Brian Brain Damage at the wheel and being lost on Ecstasy in the East Village after dark?

To be fair, the driving while tripping was the more dangerous and in hindsight that could have been catastrophic. We could easily have caused an accident and hurt other people. It wasn’t very clever, but we got away with it. We were so fucking lucky in all kinds of ways. The Ecstasy – I can’t remember feeling threatened. We were two people staggering around – me and this girl Frankie – I was wearing dark glasses, looking the way I looked, I probably looked quite threatening to people myself.

That photo in First And Last And Always in Detroit: we were told not to go out and walk around the streets in that part of town. But there we were, the four of us happily strolling around with Ruth (Polsky) having our photo taken. People left us alone.

The Sisters looked the same off-stage as on-stage in those days. You must have stuck out like sore thumbs at the Madonna concert you went to in New York?

Me and Andrew and Joey Ramone sat together. He was on the same guest-list as us. We were sat there in the stalls amongst all these Madonna lookalikes. It was nearly all 12-16 year old girls and then there was us.

A stranger sight than you and Craig in Disneyland?

You know what, I’ve been to Disneyland quite a lot after that because I lived in Orange County and not been allowed in because of a dress code. That first time with Craig, I can’t remember any dress code.

There are several degenerate moments in the book. The two low points are arson in Milan and the waterboarding of a fan with a pint of vodka in Zurich. What else are you ashamed of?

Pissing in the beer is another. The cockroaches with Mark. Ashamed is probably not the right word to use though.

Taking heroin in Hulme?

No, I don’t regret that. It’s not something I’m ashamed of. That’s how I was then. I’d try anything and everything.

Is there anything the lawyers hoiked out of the book?

No. There were a couple of things I queried with my editor and he checked it with the lawyers. One of which was basically saying I got tabs of acid from Courtney Love. And the bit about the guy she claimed to have lost her virginity to being erotically entangled with a Hoover. I was just repeating a story Pete Burns had told me. I knew the guy when he was playing guitar in The Psychedelic Furs, but I’ve never had the guts to ask him if it was true.

You tried to write a follow-up to First And Last And Always, just you and Andrew Eldritch in a house in suburban Hamburg for a couple of weeks. That was never going to go well.

I think it was more like 4 weeks. I went there thinking it was going to be in Hamburg, thinking we could go off into the bars at night. I didn’t know it was in boring, suburban Hamburg. I didn’t realise it was 10km out. We had no transport. I arrived at the airport and it was like, “The taxi’s going the wrong way!” At that time, there was no cable TV, Eldritch just had a bunch of videos all in German. It was a long, long 4 weeks I can tell you.

He had also rejected all your songs by this point. You seem quite hurt by that.

Of course I was hurt. I’d put a lot of time into them – there were 10 to 12 songs. There was enough to make an album, but I’d been in bands before where there had been weird dynamics. ”If you want to try a different route – fine.” Later on in The Mission I took the role of Eldritch in some respects: “Sorry Simon (Hinkler, guitarist in The Mission), I can’t really sing your songs.”

Eldritch gave me a bunch of his demos to work on. They were really ponderous, really skeletal, no dynamic. I’m old school: intro, verse, chorus, bridge, re-intro. There was none of that. It was basically one sequence over and over again. If you listen to Floodland and the album after that, basically all of those songs are one riff, over and over again and he just overlaid some dynamics on it, which worked, certainly on things like Lucretia and Dominion.

Do you think Eldritch was trying to see if you would tolerate going back to being a sideman, rather than a writing partner, an equal?

Absolutely it was. I was basically going back to the situation I’d encountered in Hambi and The Dance where I’d actually contributed whole chunks of songs and the guy was trying to claim credit. However, I was prepared to go along with it at that point with Andrew to see where it went.

Craig was also pissed of with him by that point too. When Andrew came back to Leeds, it didn’t take much to light the blue touch paper. It was the first day of rehearsal when Craig threw his bass down and walked out. In the book I write about a lot of conversations, most of the words are how I remember the gist of the conversation rather than the actual conversation, but when Craig left I vividly remember Andrew turning round to me and saying, “Well we’ve got rid of the driftwood now.” I remember those exact words.

When I went back the next day, Eldritch asked me at that point, if I would still play on his next record. “If you want to pay me to play guitar, fine, I’ll come and play guitar on your record.” But I didn’t want to be in a band with him any more.

You refer to The Sisters as “a diversion, not a destination”, what did your two years in the band contribute to you as a musician and a person?

Obviously it led to The Mission. The first lot of tunes The Mission recorded were songs I had written for The Sisters. The Mission really began when Craig and I left The Sisters. We didn’t try to be different to what we’d been doing before, in fact on the contrary, we wanted to be more like what we’d been doing before.

Being in The Sisters and taking that next step up gave me the confidence to take on the role of being the singer in the next band. I’m not sure I was ready for it before, although I had sung in other bands. I’d always felt more comfortable being the guitarist. Even when The Mission started, I didn’t have the intention of being the singer, but events overtook me. The Mission have been around for nearly 35 years, so I would say The Mission was my destination and ultimately The Sisters was the final step to finding my home.

What music are you most proud of in the time period covered by the book?

Songs?

Doesn’t have to be whole songs. For example, it could be the encore with The Sisters at the Melkweg in Amsterdam. In the book you seem very proud of that, playing guitar and effectively playing the drum machine at the same.

To be honest, I don’t have any memory of that, I’m just going by what Dave Allen told me. He wrote a whole piece for me and I thought, “That’s fucking cool!” but I can’t remember doing it.

I like the first thing I ever recorded for Dead Or Alive – Whirlpool. You can definitely hear what The Mission became in that song.

First And Last And Always obviously, as a whole and Marian in particular. After that album, I felt creatively drained. Obviously, I hadn’t put as much emotionally into the record as Andrew had, but I did feel at that point like, “I don’t know if I can make another record.”

Marian I came up with start-to-finish in the studio one day – the whole track, bass, guitars, everything. All the other songs had been demoed. Sonically, I listen to it now and think, “What was I doing there?” That song, the way the guitars interweave is alchemy. Wow – I can’t work out what I’d done, listening to it now. I love records where you can’t work out what instrument is doing what and to me Marian sounds like that. It was one of those moments – I surrendered to it. Those creative moments make everything else worthwhile.

The first time I went on stage; I’d only been playing guitar for a few weeks. Blueprint was my first band. We played a bunch of my songs and I had managed to learn how to play Soul Love by Bowie. Although we must have been totally rubbish, I loved it. I thought, “Yeah, this is what I want to do.”

More information on “Salad Daze” and how to pre-order it, can be found on The Mission's Facebook. There are fan bundles available via The Mission's merch store. It's also available on Amazon.

Mark Andrews’ book on Leeds and the rise of The Sisters of Mercy, Paint My Name In Black and Gold, is now 100% funded via Unbound and will be published in 2020. You can pre-order the various editions at Unbound.