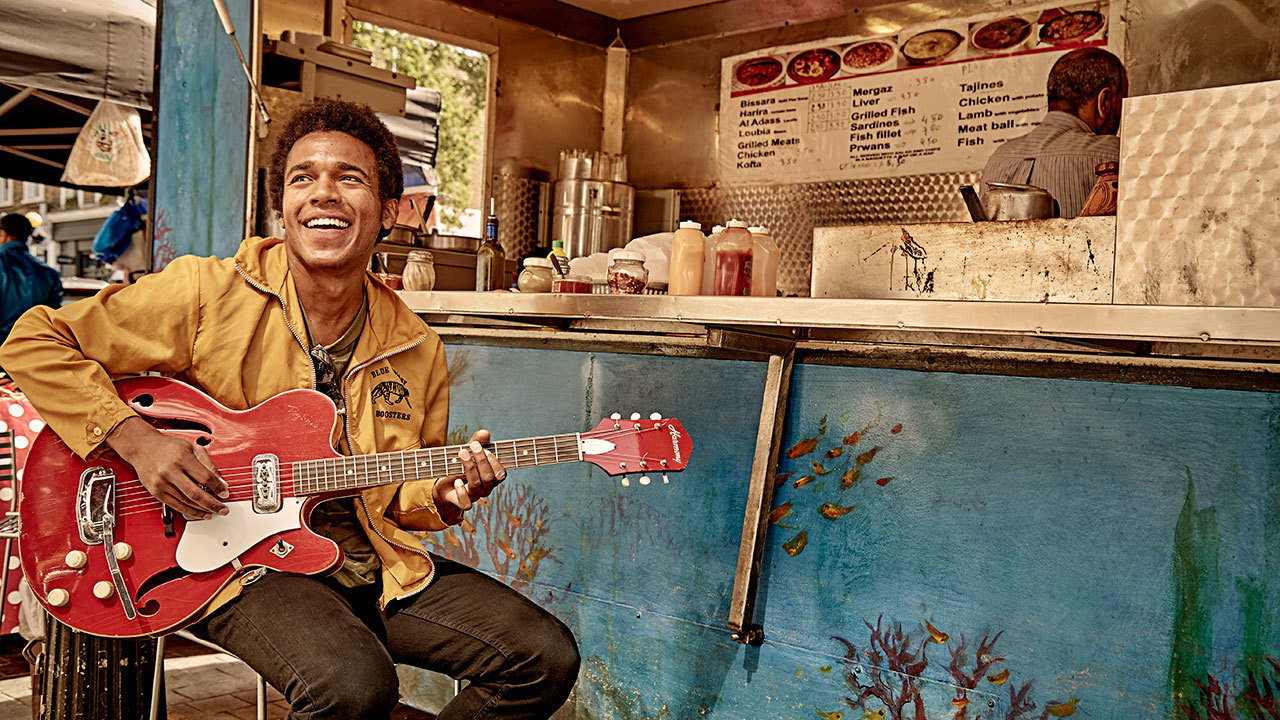

Munching a doughnut after our photoshoot in London’s Portobello Road, Benjamin Booker is feeling sleepy but in good spirits following his appearance last night on Later With Jools Holland. He’s also quietly cool and confident, compared to the bundle of nerves we saw in 2014 when he released his self-titled debut album.

“Those first songs were written without knowing that people would see them. I wasn’t signed or anything, so it felt really uncomfortable playing them in front of people,” the 27-year-old says. “This time, knowing I was going to share it with other people, I was like: ‘I’m going to make something I’m proud of,’ so I’m excited to share it with people.”

After his debut, everything went mental.

Booker didn’t really play until he was 23 (“I avoided the sappy high-school albums people have,” he says with a chuckle). Two years later, in 2014, having swiftly made a name for himself on the New Orleans live circuit, he released his debut. Famous names including Jack White and David Letterman came calling, and touring grew heavier. Booker says he drank every day for two years. “I got home and I really looked terrible,” he says. “It was really bad. I was young, straight out of college, and I was thrown into a situation where somebody would say: ‘Here, free stuff all the time! Whatever you want!’”

A trip to Mexico changed everything.

By February last year, Booker was exhausted and in need of new material. On a whim he flew to Mexico, where a lot of soul-searching and some racial tensions (something he was no stranger to) helped him created the blueprint for his new album, Witness.

“I was reading a book called White Noise on the plane over there,” he recalls, “and there was a section that said: ‘What we are reluctant to touch often seems the fabric of our salvation.’ I realised I wasn’t a good person; it’s not enough to have good intentions, you have to do good things all the time.”

Witness is a funky record.

Compared to the raw garage-punk rock of his debut, Witness has a much richer sound (not to mention a bigger band, including a crack squad of backing singers), drawing from T.Rex, Pops Staples and Fresh by Sly & The Family Stone. “I always loved T.Rex,” he says. “And I was listening to a bunch of funk stuff from Africa from the seventies. That’s pretty big in America – William Onyeabor is huge and I love him.”

Booker was a punk until he discovered Robert Johnson.

When he was younger, Booker frequented DIY punk shows in Florida. Then one day, aged about 16, he picked up a Robert Johnson album in a used-CD shop. “It was so different to everything I’d heard,” he remembers. “I think music at the time was pretty full-on, and it was really comforting to listen to something that was so stripped down. To me, the most important thing [in music] is the song itself, the melody. Listening to the blues when I was younger, a lot of it’s just an acoustic guitar and a guy singing. If you can pull that off, it passes the test.”

Hurricane Katrina took him to New Orleans.

It wasn’t New Orleans’ illustrious music reputation that drew Booker away from Florida. Lost and directionless, post-college, he became a volunteer with AmeriCorp and headed to the Big Easy to help with the post-Katrina clean-up. “I didn’t know anything about New Orleans,” he admits. “But when you move there, everyone is so into the music. And their radio station plays the best stuff all the time, it’s all local. So that fed into the first album.”

He now lives the good life in Los Angeles.

After a nomadic few years, Booker now lives a healthier life with his girlfriend. In his spare time he volunteers, teaching children creative writing.

“Things are pretty crazy now in America, and in the UK,” he says. “It’s easy to get overwhelmed. But it’s been helpful for me to do things like volunteering, donating money to people, reading about what’s going on and staying educated. I think if people do those kinds of things, we’ll all be alright.”

Witness is available now via Rough Trade.