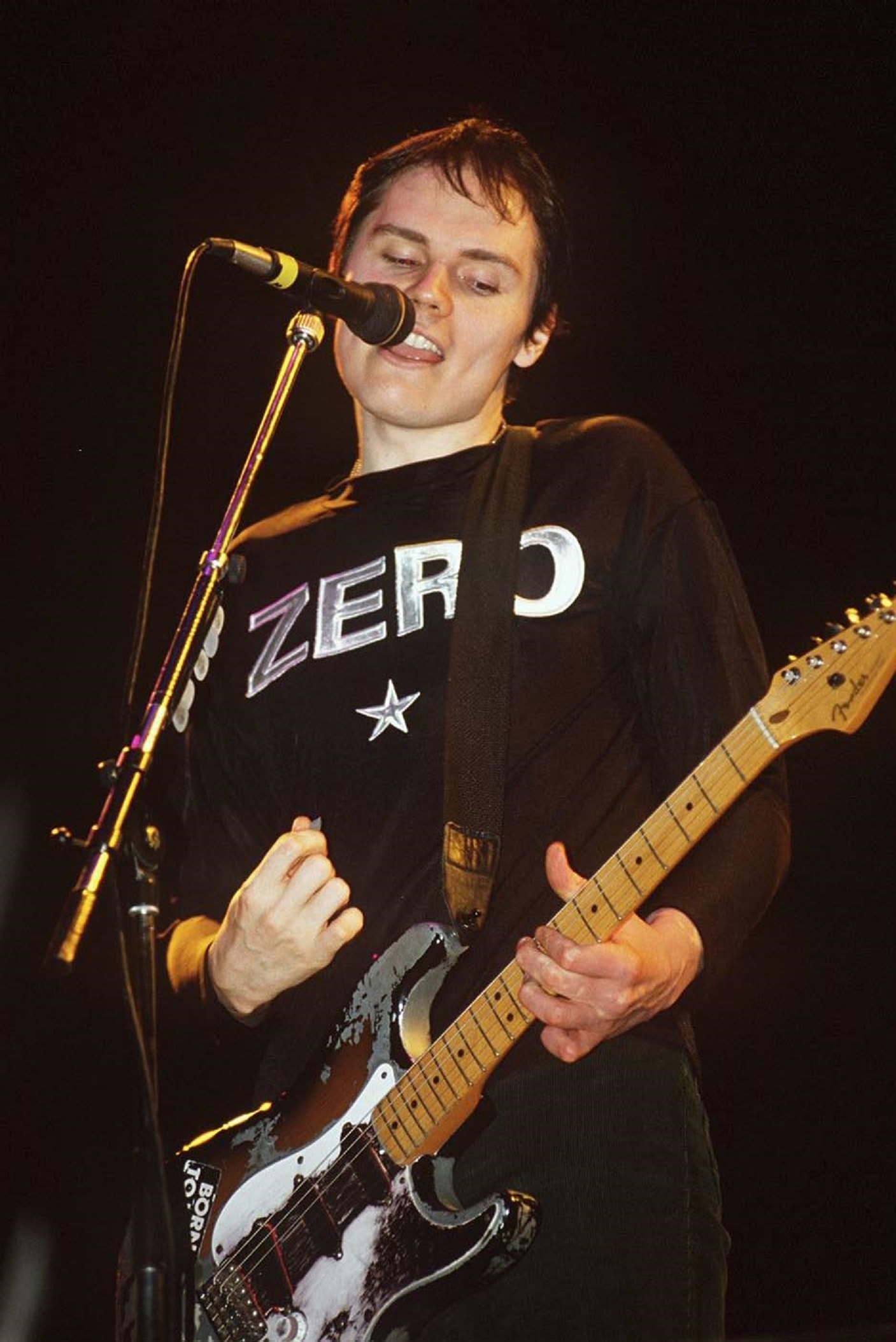

It’s about 10 minutes into the conversation when Billy Corgan declares himself a musical genius. “I am,” says the Smashing Pumpkins frontman, “arguably the best songwriter of my generation.”

Coming from anyone else, this would sound like hogwash. But Corgan hasn’t spent the last 20-odd years hiding his light under a bushel. In their original incarnation, the Smashing Pumpkins were the grandest rock band of the 90s, yoking stadium rock ambition to alt-rock invention. At their best, on 1993’s Siamese Dream or 1995’s Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, they came on like a grunge Queen, with all the fearlessness and foolishness that suggests. Their records sold by the bucketload, and for a while they were one of the most-talked about bands around.

But in an era when such ambition was frowned upon, there was a price to pay. For certain music fans, journalists and fellow musicians, William Patrick Corgan Jr. became a figure of ridicule. Over the years, he’s been variously described as a megalomaniac, a control freak and “a baldy twat”. It stung back then, and today, in the darkened basement jazz bar on one of London’s more upmarket hotels, it still stings.

“My band’s been hugely influential, musicians constantly cite me as an influence, I’ve written more than 500 songs, but I’ve been turned into something that isn’t that guy,” he says.

What is Billy Corgan’s problem with the world? And more importantly, what’s the world’s problem with Billy Corgan?

“I dunno,” he says, looking momentarily sad. “Maybe I’ve just told the world to fuck off one too many times.”

If you met Billy Corgan in a pub, you wouldn’t peg him as a rock star. A big, full moon head sits atop of thin, stooped shoulders; his black-and white striped T-shirt and teak-brown leather jacket look like they’ve been fished off the racks at the back of Oxfam. He’s taller than you’d imagine, though just as intense: he frequently gazes at the table in front of him, and his drawn-back smile is a close cousin to his pained grimace. The overall impression is a grown-up, mildly depressed Charlie Brown.

But Billy Corgan is definitely a rock star, and a successful one at that. In the 24 years since he formed The Smashing Pumpkins in his native Chicago, he’s sold somewhere in the region of 35 million albums – fewer than Nirvana and Pearl Jam, but as many as Alice In Chains and more than Soundgarden. He’s an in-demand collaborator, too, with a dizzyingly schizophrenic CV: few other artists can say they’ve worked with Ray Davies, New Order and The Scorpions. “I was walking down the hall, and they said, ‘Hey, do you wanna come and work with us’,” he says of the latter. “Klaus Meine is super-passionate, very earnest, very genuine. That desire – ‘We want to rock you’ – has always translated to their fans. There’s a beautiful spirit with a band like that.”

It’s this sort of talk that set Corgan apart from his original peers in grunge’s Class Of ’91. The Pumpkins released their debut album, Gish, just as that particular party got into full swing, but they always felt like gatecrashers – the sullen kids in the corner who no one wanted to talk to. This was partly geographical: they hailed from the terminally uncool Midwest rather than the punk rock hipster enclave of Seattle. But it was mostly musical. As the driving force behind the Pumpkins, Corgan was ferociously ambitious. While every other band of the era was worshipping at the altars of the Stooges and Sabbath, Corgan was citing The Cure, Cheap Trick and Queen II as his touchstones.

“We came to the UK for the first time in 1992,” he says. “It wasn’t comfortable. We were getting bad reviews, we weren’t as cool as EMF or whatever the fuck the press were on about at that minute. But there was a sense something was happening, and that it was actually going to mean something.”

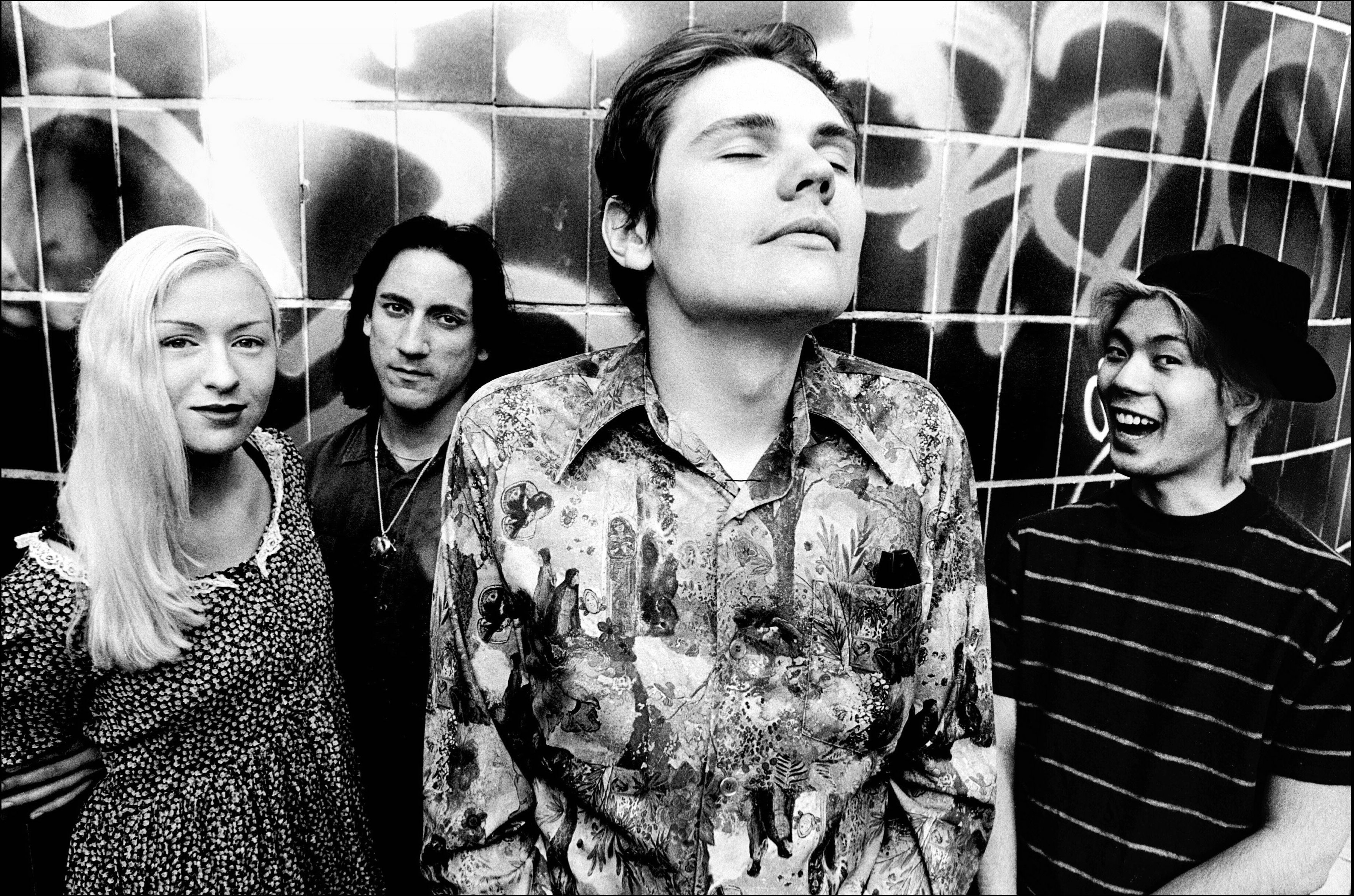

It did. Gish’s mix of fuzzy grandiosity and tightly-knotted rock’n’roll helped propel it to platinum status. But there were problems behind the scenes. Corgan’s perfectionist tendencies found his bandmates – particularly guitarist James Iha and bassist D’Arcy Wretzky – relegated to the role of ‘the help’. By the time of 1993’s follow-up Siamese Dream, Corgan was both writing the songs and playing all the instruments expect the drums.

“My attitude then was, ‘Hey, it’s not my fucking fault you didn’t practice like I did and you can’t play the songs’,” he says. “It was more callous: ‘The clock’s running, we gotta make this work’.”

The internal strains didn’t slow down Corgan’s prodigious work rate. The Pumpkins third album was the double-disc Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness. As epic, and occasionally overblown, as its title, it owed more to Styx than The Stooges. Flying in the face of prevailing trends, it shifted more than nine million copies in America. Kurt Cobain was dead, Pearl Jam had beaten a retreat from fame, and Alice In Chains were in drug-induced disarray. Suddenly, Billy Corgan, perpetual misfit, was the king of the castle. And he hated it.

“It was not fun being in a band with two drug addicts and one major pain in the ass,” he says, referring respectively to Wretzky, drummer Jimmy Chamberlin and Iha. “That wasn’t me, by the way. I was the other pain in the ass.”

In July 1996, while touring in support of Mellon Collie…, tragedy struck. Keyboard player Jonathan Melvoin died and Jimmy Chamberlin was hospitalised after overdosing on heroin before a gig at New York’s Madison Square Garden. Distraught and angry, Corgan fired Chamberlin, leaving the band as a three piece. This new configuration would record 1998’s misfiring Adore, a record that ditched the Pumpkins’ stadium-sized alt-rock for wooly electronica. Their cause wasn’t helped when Corgan loudly proclaimed that: “Rock Is Dead.” He laughs loudly at the memory.

“Ha! I just said it to be a pain in the ass. But I was being honest, I did see where it was ending. What surprises me is that 15 years later, it hasn’t really come back. I’d have thought by now that there would have been a new Nirvana or a new Radiohead. You and me should be arguing about the five greatest records of the last few years. The fact that we can’t just go, ‘Boom – it’s that one’ says something’s changed. Why are all these great artists suddenly incapable of finding that great moment again. That’s weird, right?”

So what’s changed?

Rock’n’roll is maybe too old and has been done too many different ways. Maybe there’s no new tool in the toolbox. It’s gonna take a technological leap, to where people are gonna experience music differently or watch the concert and interact differently. It might be a situation where 70 per cent of the audience is blogging and tweeting at the same time, and somehow it’s informing the show.

So if rock is still dead, are you saying it’s the fault of the artist or the audience?

(Laughing) I blame the audience.

Of course, Corgan is conveniently overlooking the fact that he hasn’t exactly done much to help resuscitate rock in the interim years. Since splitting the Pumpkins in 2000 (“I should have stopped right after Jonathan died and Jimmy left, but I had a deep sense of loyalty to the people I’d started the band with”), his career has followed a decidedly wonky path. His indie rock supergroup, Zwan, fell apart after just one album. A dreary, electronic-heavy solo album was ignored by all but the most partisan fans of his old band. When he bowed to inevitable pressures and put the Pumpkins back together in 2005 – with Jimmy Chamberlin but without his old bête noires James Iha and D’Arcy Wretzky – the resultant album, Zeitgeist, was a big, clod-hopping dud.

But recently, Corgan appears to have rediscovered his mojo. In 2009, he announced a new project for the Pumpkins. Inspired by the Tarot, Teargarden By Kaliedyscope was an endeavour as grand as its title: a collection of 50 songs, recorded and released sequentially and given away free online over a period of months years. “I don’t think I’m going to make albums in the old-fashioned way,” he said at the time. “My desire at this point would be to release one song at a time, over a period of two to three years, with it all adding up to a box set/album of sorts that would also include an art movie of the album.”

By May 2011, there were 10 songs available online, gratis. They were as fine as anything he’s ever recorded: ambitious, ornate, simultaneously forward-looking and gloriously retro. The sort of thing that really do make you wonder if he really is the greatest songwriter of his generation.

And then, suddenly, two things happened: first, the free songs dried up, and second, Corgan announced that the Smashing Pumpkins were making a new album,* Oceania*. That’s ‘album’, as in an old-fashioned collection of songs. brought together in one place, available in exchange for cash money. Exactly the sort of thing he’d proclaimed he’d left behind.

“I said, ‘OK, we just have to make a really exciting album, and I don’t care what it sounds like. It doesn’t really sound like Smashing Pumpkins. It’s still rock’n’roll but something’s different about it. Maybe it’s a little more spacey.”

It’s a bit of an about-face. What happened to the grand project to give away all these songs?

I think I was just bored with one song at a time. Maybe I was trying too hard. And I was surprised that ‘free’ meant absolutely nothing.

That sounds like people weren’t picking up on the songs.

No. And not only that, they don’t know they even exist. Maybe I should have made a big deal out of it. But I looked at it as an organic process – let’s put the songs out and see what happens. Let’s not come in on the horses to Ride Of The Valkyries, going, ‘We’re back!’ We’ve done that, it really didn’t work.

What’s the theme of the new album?

Isolation seems to be the theme. Oceania – there’s something about the idea of being an island, or being an astronaut. A sense of displacement.

Does that reflect where you’re at right now?

[Massively ironic laugh] I don’t know if you took psychology in college, but yeah, you can go there if you want.

Okay, let’s go there. Why does a successful and rich rock star feel displaced at this point in your career? Or at least more than you were 15-20 years ago?

I don’t feel any more displaced. It’s why I continue to feel displaced. I’ve watched other people of my generation get to become mainstream stars by just being thumbs-up and smiley. I find it all annoying. I’m, like, ‘Am I gonna be on the outside always?’ That’s the public part. Privately there’s a different reflection, which has to do with relationships and love and no kids. All those things blur.

Let’s lighten the subject. You’ve recently set up your own wrestling league. Tell me about wrestling…

[Non-ironic laugh] That’s heavier! That carries with the weight of judgment.

Right. What do you get out of wrestling that you don’t get out of the band?

There’s a sense of community in the wrestling world that I don’t get in the rock world. I’m not embraced in the rock world. I’m just not.

And right there, in three minutes of conversation, you have everything that makes Billy Corgan so intriguing and so frustrating. There’s the unassailable confidence and sense of self that has made him one of the grunge era’s great success stories. And then there’s the overanalytical therapy-speak and aggressive self-pity that has resulted in mockery from everyone from his Sharon Osbourne, who managed him for about three seconds around Adore (she called him “a baldy twat in a dress”), to former girlfriend/collaborator Courtney Love (“He coughs up this spiritual shit like bile and lives none of it”). Why does he draw such vitriol where, say, Chris Cornell doesn’t?

“I can’t answer that, though I wouldn’t mind speaking ill of Chris Cornell,” he says, with a smirk. “Sharon and I are cool. We’ve made up and I’ve hung out with her. Courtney’s just insane.”

It’s a fair guess to say that Billy Corgan will never be entirely happy with his lot, or at least how he’s perceived. But it’s difficult to not admire his resolve as he ploughs on, the slings and arrows of his detractors bouncing off his rhinolike hide. As well as Oceania, he says he hasn’t abandoned the Teargarden… project. Then there’s the wrestling league, a sort-of autobiography (“I’m calling it ‘a spiritual memoir’…”), and, bizarrely, a 1930s Chinese-style teashop he’s opening in Chicago. “It’s a little bit of a salon vibe,” is his explanation for the latter. “Very old school.” For a 44-year-old who calls himself an “outsider”, he’s keeping himself busy.

Do you still feel like an outsider?

I am an outsider. I don’t feel like one. If you’re treated like an outsider and they write about you like an outsider, then you’re an outsider. I can’t tell you why. I should be an insider, that’s my point.

Is there anything you can do to become an ‘insider’?

No, I won’t compromise at that level. What constitutes a happy rock star in the modern world, in 2012, is fucking boring. Won’t do it.

Our time is up. He offers a quick hand and then he’s up like a shot, striding across the room and out the door like a human cueball. There he goes, the best songwriter of his generation. As alone as ever.

Click below to read our defence of the often overlooked, and much maligned, Smashing Pumpkins album, Adore.