April 29, 1991. A leaden grey sky hangs oppressively over St. Anastasia’s Roman Catholic Church on 245th St, Queens, as friends and lovers, united in grief, gather to pay their final respects to John Genzale; husband, brother, son and father. Mariann Bracken has lost the prodigal kid brother she’d introduced to the New York City melodramas of the Shangri-Las when he was just a fresh-faced altar boy. Leee Black Childers is inconsolable – the former manager of the deceased fainted when informed of his death – unable to imagine life without the man he was “totally” in love with. Susanne Blomqvist, only now realising the true depth of sacrifice her life partner made when he walked out of the home they shared with their infant daughter for the last time, absently registers the names on the cards of the numerous floral tributes piled on the back of a black El Camino: Deborah Harry, Mötley Crüe, Aerosmith – a stark reminder of Genzale’s other life, the one that always seemed to get in the way of their ephemeral moments of domestic bliss.

As the service draws to a close, St. Anastasia’s: reverberates to the sound of You Can’t Put Your Arms Around A Memory. There’s not a dry eye in the house. Johnny Thunders: a Heartbreaker right to the bitter end.

On arrival at the interment, Jerry Nolan – to all intents and purposes his elder brother, father figure and unrequited other half – is handed a rose, which he gently kisses and places with due ceremony on the coffin lid: a poignant tribute, yet brief. Jerry has been drowning his sorrows with fellow New York Dolls alumnus Sylvain Sylvain, and both, in immediate need of relief, head for a nearby convenience. With nature’s call duly answered, the pair return to the graveside and find it deserted. They made the gig, but missed the encore. The curse of Thunders strikes again.

Jerry looks at Syl, Syl looks at Jerry, and as Syl hurls the first fistful of soil into the grave and onto the coffin lid he yells: “JOHNNY, YOU MOTHERFUCKER!”

Johnny Thunders’s story is so steeped in doomed glamour and junkie mythology that somewhere along the line the man that was John Anthony Genzale has been lost in the telling, but to know one you have to know the other. Born in the middle-class Jackson Heights area of Queens on July 15, 1952, the boy who would be Thunders was irrevocably shaped in infancy by the departure of his father Emil Genzale. A serial womaniser of no little prowess, Genzale Sr ultimately chose swordsmanship over fatherhood, leaving little Johnny to be brought up by his mother Josephine and doting elder sister Mariann.

Haunted by rejection in his formative years, yet indulged by his matriarchal Italian upbringing, the young Genzale grew up spoiled but unsatisfied. Initially infatuated by baseball, he finally found a focus for his adolescent anger and angst in the perpetual soundtrack of Brill Building rock’n’roll drifting across the hall from his sister’s Dansette; shrill, urban dramas of switchblade romance and leather-clad Lotharios, delivered by keening teenage girls teetering on the brink of hysteria.

As Genzale matured he developed musical tastes that reflected his self-image. A born dandy with a taste for the urban blues, haphazard ebony locks, and a rebellious streak the width of Broadway, it was inevitable that he should come to idolise Keith Richards. Entranced by rock’n’roll, Genzale made the leap from observer to protagonist in his mid-teens.

“Me and my cousin Janis used to go to the Fillmore East every Saturday,” his childhood friend Gail Higgins remembers. “Johnny and his friends would be on one side of the room, and we’d be on the other, staring at each other.”

The 16-year old Johnny and Janis eventually started dating. They rented an apartment on New York’s First Avenue, where Johnny took up the bass. They caught shows by The Who, The Hollies and Small Faces, they drank beer with Rod Stewart backstage at the Newport Folk Festival, and Johnny was even captured on film gazing in awe at Keith from the front row of Madison Square Garden in the Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter. In 1969 they travelled to London to sample the scene. But it was the sound of Detroit that particularly struck a chord with Johnny.

“We would drive eight hours to see the MC5 or The Stooges,” Gail attests. It wasn’t long before Johnny abandoned the bass and set about learning the guitar. “Whenever he was practising, I used to yell into the bedroom: ‘Give up, Johnny’,” says Higgins.

Never one to blend into his surroundings, Johnny always stood out from the crowd: long, spiky hair, and a penchant for borrowing his girlfriend’s clothes. His style was extreme. “He had high-heeled boots, velvet jackets and pants, bowling gear,” says Heartbreaker Walter Lure. “I’d see him at all the shows – mostly the British bands, as opposed to the Grateful Deads and Jefferson Airplanes – so I’d seen him around for years. Then when the Dolls started happening I said: ‘Holy shit! There’s that guy.’”

The New York Dolls’ seismic effect on rock’n’roll has already been covered in forensic detail elsewhere. Suffice to say, in the admirably concise words of Richard Hell, “The Dolls were for New York groups what the Sex Pistols were for British groups.”

The Dolls’ rapid ascent from Manhattan drag bars to Wembley Empire Pool (now the Arena) elevated the expectations of the newly renamed Johnny Thunders through the roof. Tragically, though, his relatively short tenure with the Dolls spoiled him in ways that were far more damaging. On November 7, 1972, in London after supporting The Faces at Wembley, Dolls drummer Billy Murcia was accidentally drowned by party-goers trying to arouse him from a certainly survivable champagne and Mandrax haze by immersing him in a bath of cold water.

It was a messy, senseless and avoidable death that left the band shell-shocked. Gail Higgins: “Johnny was devastated. He was the closest with Billy and it really upset him. Johnny was very sensitive and loving, very needy and very insecure.”

“Billy’s death was the beginning of the end for the Dolls,” believes Leee Black Childers, then Vice President of MainMan, the management company that looked after David Bowie. “Because then Jerry Nolan came in, and Jerry was so self-destructive. He addicted Johnny Thunders to heroin.”

“Jerry was seven years older than Johnny and their relationship was more than just brothers,” says Nolan’s former partner, NYC punk scenester Phyllis Stein. “At times, as Jerry would tell me, he felt like Johnny’s father.”

“It was real father-and-son type stuff,” agrees Walter Lure, “because Johnny would look to Jerry for approval. In the Dolls, when John got out of control on drugs, the band would ask Jerry to take him into a room and give him a couple of whacks to the head, and John would calm down. I saw Jerry go up to John and say: ‘Listen, you wanna get a smack in the head?’”

Gail Higgins: “Jerry was very, very protective of Johnny. He was the older guy. Obviously they did drugs together, but they had a love-hate relationship, they fought all the time, but they loved each other deeply.”

Leee Black Childers: “Johnny and Jerry were one of the great unrequited love affairs. They fought like lovers, broke up like lovers, reunited like lovers. Jerry would manipulate Johnny, making him crazy, then Johnny would break down in tears and Jerry would storm off, and Johnny would lay in my lap crying: ‘Where’s Jerry? I can’t live without him, I can’t work without him, I can’t be without him.’ That sounds like lovers to me.”

It wasn’t just brotherly love, fatherly discipline and a solid backbeat that Jerry Nolan brought to Thunders’s emotionally charged, high-pressure lifestyle. The drummer was an evangelistic user of heroin, and Johnny a willing convert. Still distraught from Billy Murcia’s death, and eager to impress the worldly Nolan, the guitarist took to heroin like a duck to water. Thunders wasn’t clean prior to Jerry’s arrival – he’d been previously introduced to smack by a pair of A-list rockers still working today – but it was allegedly Jerry that recommended regular fixing to Thunders as an answer to all that ultimately ailed him.

Gail Higgins: “He started taking downers first, he didn’t suddenly start taking heroin. It was a mask, he was insecure and the type of person who just cannot be happy.”

“Shyness is one of the reasons why I got involved with smack,” says former Heartbreakers bassist Billy Rath. “And smack helped to remove Johnny’s shyness. One of the reasons he never really pursued getting himself together was because he felt that if he cleaned up and got rid of his habit he couldn’t be Johnny Thunders any more.”

But while heroin was helping Thunders to cope, it wasn’t without its side effects. Before drugs took hold, the guitarist was quiet and meek. When he started taking heroin he became obnoxious. Sylvain Sylvain: “When he became a junkie he turned into a fucking monster and it made him aggressive for no reason, because everything is boring until you’ve had a fucking fix. It rules everything and it ruins everything.”

As the New York Dolls’ career steadily unravelled, a junk-sick Thunders and Nolan bailed on the band in Florida in 1975, returning to New York to make their connection. As Dolls vocalist David Johansen eruditely understates it: “The problem with [heroin addiction] is that a person in that condition has to have their medicine available. So it limits one’s mobility, not to mention the myriad other things it limits. So you can’t travel freely, because you have to be looked after in that department.” The shattered Dolls returned to Norfolk Street, scored some Chinese rocks, and prepared to break some more hearts.

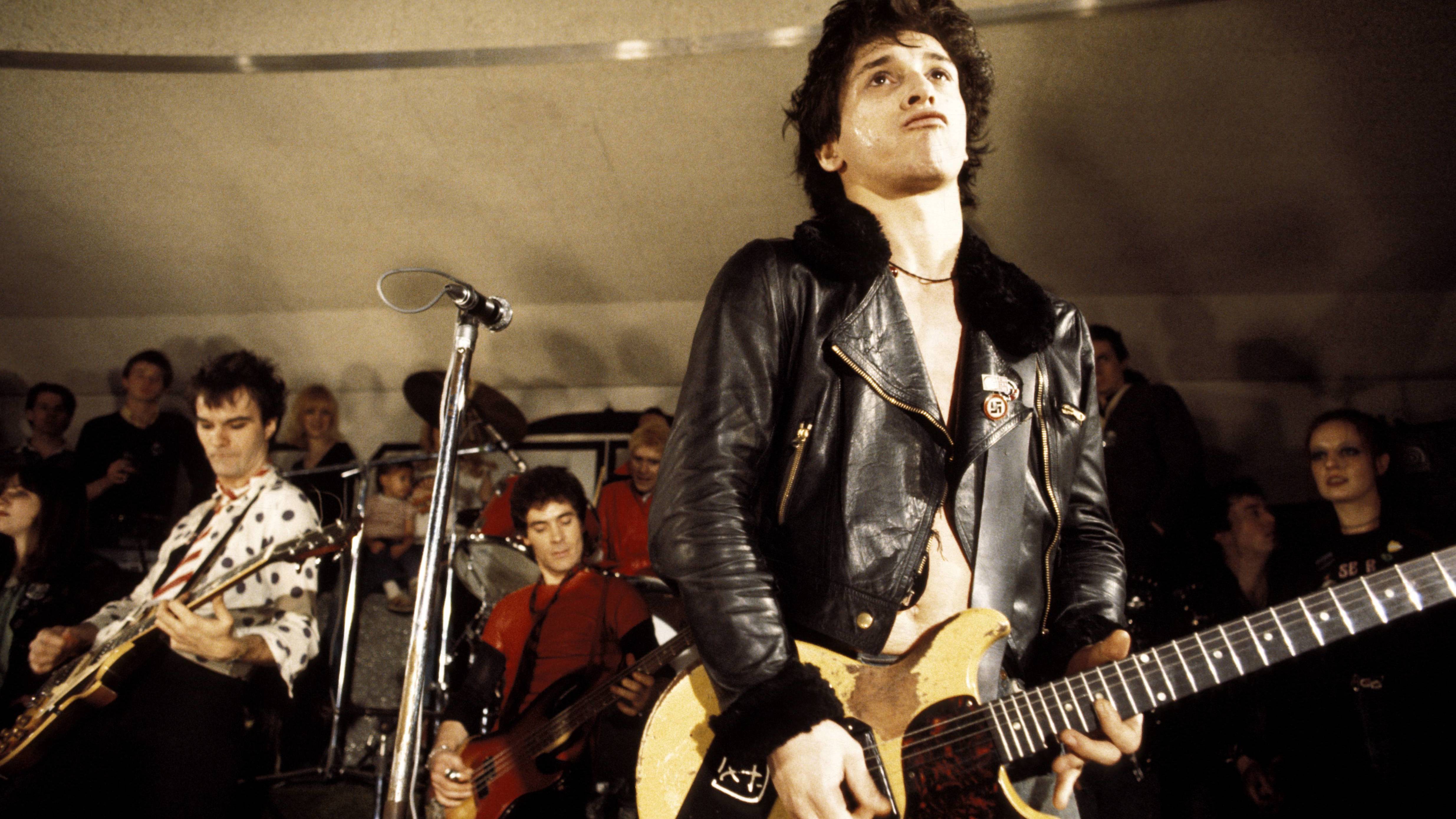

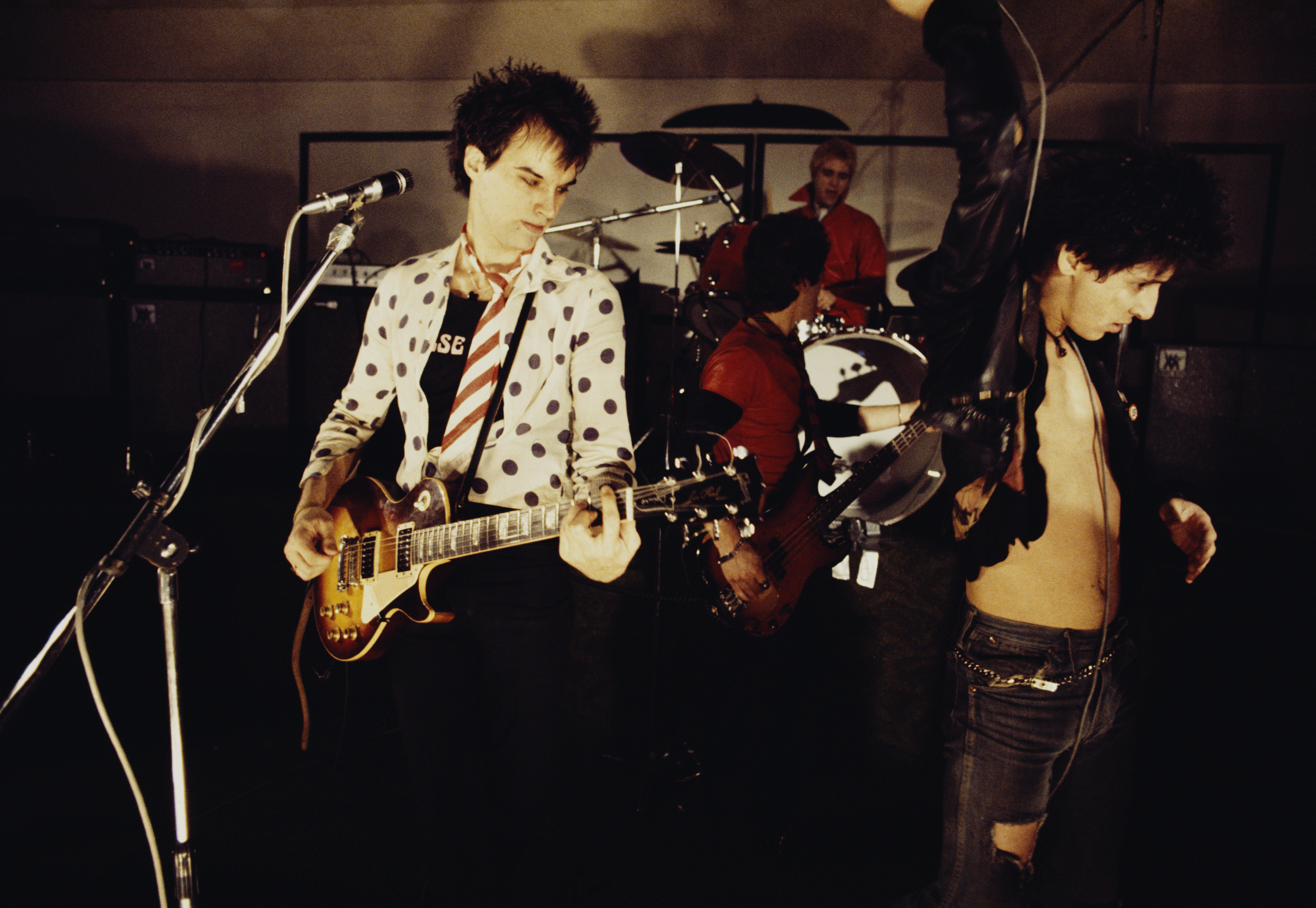

Following a false start with Television bassist Richard Hell, Thunders’s new band, The Heartbreakers (now comprising their classic, fat-free Thunders/Lure/Rath/Nolan line-up) casually wowed New York City’s club scene. But it soon became clear that no American record company was ever going to sign a band that featured Thunders and Nolan. Enter Malcolm McLaren offering a UK tour slot supporting the Sex Pistols. The Heartbreakers practically bit his arm off.

The band arrived in Britain on December 1, 1976, the day the Pistols appeared on Bill Grundy’s Today show. Consequently the majority of the tour they had flown in to play was cancelled in a blaze of tabloid headlines. Leee Black Childers had become their manager by this point. “We were freezing,” he says. “The Heartbreakers, Sex Pistols and Clash on this rickety old bus. Johnny couldn’t care less, he’s laughing, carrying on. He kept the spirits up on the bus. It was like the old days of vaudeville – the show must go on.”

Returning to London broke, and, consequently clean, The Heartbreakers made an appearance at the Roxy club attended by all the prime movers of the nascent UK punk scene. But it was more than just a winning personality and a crack band that Thunders brought to London’s punk rock party. Glen Matlock: “Until The Heartbreakers turned up in London I hadn’t heard the word ‘heroin’ mentioned in our circle.”

Steve Dior a was fan of the Dolls who later became Thunders’s protégé. He was 17 when he saw The Heartbreakers at The Roxy. “I was standing in front of Thunders, at the front of the Roxy stage, studying him,” he says. “I went to the dressing room, poked my head in, Johnny looked at me and said: ‘Are you famous or something?’ And Jerry said: ‘He fucking looks like you.’

“I started hanging out with them. Johnny decided to teach me to play like him. Then he found out that I was banging up speed and said: ‘Come on, kid, you wanna be doing the real shit.’ He took me in hand. But there was a price to pay: ‘You wanna play like me? You’ve gotta party with me. How much money you got?’ I put in about a hundred, we went up to Mayfair and that’s where we did it.”

Thunders’s drug problems, meanwhile, only worsened. Leee Black Childers: “We would have a bucket behind the amp, so he could go over and throw up. But then he would go right back and put on the most amazing shows. At one point he was supposed to be on Methadone. I would measure out his ounce of Methadone and watch him drink it in front of me. But he’d keep the methadone in his cheeks and spit it into a cup, until he had a week’s worth. He was using heroin, and saving the Methadone so that he could have a big weekly high as well.”

It was at this point that Johnny decided to fly his soon-to-be wife Julie Jordan, John Jr (Julie’s two- year-old, from a previous relationship) and their baby, Vito, to London. Having dated since The Heartbreakers’ early days, the couple married on August 16, 1977.

“It was fucked up,” remembers Walter Lure.“They got married in New York, and they were both throwing up in the back of the limousine because they had too much drugs. Julie was a pretty girl but she also had serious mental issues.” Gail Higgins: “That was one of his ‘If I have a family, I’ll be happy’ moments. What can I say? She did nothing, knew nothing, didn’t add anything. But because of Johnny’s insecurity he wanted her to be there every minute, and that caused friction with the rest of the band.”

Leee Black Childers: “Julie wanted to rule the roost but she didn’t know how. I only knew the babies as toddlers. Vito was just crawling. Johnny called him The Sprog.”

Phyllis Stein: “Jerry refused to attend Johnny’s wedding because he felt Johnny was making a mistake.”

During the chaotic summer of 1977 The Heartbreakers, with the appositely named Speedy Keen at the controls, holed up in The Who’s Ramport Studio in south London to record their single shot at vinyl immortality. L.A.M.F. (Like A Mother Fucker) was the muffled sound of a watertight live band drowning in a sea of over- produced mud; the mix was so bad that The Heart- breakers ultimately split.

“That mix can be completely laid at the door of Jerry Nolan.” says Leee Black Childers, “He went into this kind of control freak thing where he had to mix it. But everyone was stoned. Walking into the studio was like walking into a crack house. I should have gotten a gun and shot a couple of them dead.”

Walter Lure: “We were told we needed to release it in time for Christmas because they needed to make some money. So they just put us in a room and said if it doesn’t get released you’re not gonna have a contract. Johnny, Billy and I said yeah; Jerry said no, he was leaving, and just walked out.”

Nolan didn’t just walk out on Thunders; he took his protégé Steve Dior with him. With Barry Jones on second guitar and the New York Dolls’ Arthur Kane on bass, Nolan’s band The Idols were soon the toast of New York City. The Heartbreakers soldiered on, but Thunders was devastated by what he saw as his closest friend’s betrayal. Leee Black Childers remembers the moment he quit as The Heartbreakers manager: “Johnny came up to me and just looked with those huge, dark eyes of his, put his arms around me and said: ‘I know what you wanna do and it’s okay, I’m okay.’ He hugged me really tight. And when he hugged you he wouldn’t let go. He would just hold on and on. And then finally when he let go, that was it, that’s how I left the Heartbreakers.”

Now ostensibly solo, the guitarist took to playing guerrilla gigs around London with an all-star cast of eager celebrity fans, including Steve Jones, Paul Cook, Phil Lynott, Peter Perrett and Sid Vicious, some of whom shared a certain predilection. Thunders wanted to call this ramshackle revue The Junkies but, shot down in flames by his latest manager, BP Fallon, opted instead for The Living Dead. Steve Jones: “The times that me and Cooky played with him, he just fucked off with the money. We accepted it because that’s the way he was – just get a bit of cash to get a bit of dope and that’s all he really cares about. Unfortunately it just got worse and worse and he got lower and lower.”

The album that grew out of The Living Dead gigs turned out to be something of a classic. So Alone, released in 1978, was bolstered by Chrissie Hynde, Steve Marriott and Brooklyn chanteuse Patti Palladin. Conspicuous by his absence was Sid Vicious, who had by now decamped to New York City to make some live appearances, backed by The Idols. Vicious’s subsequent death had a devastating effect on Johnny.

Peter Perrett: “He wrote Sad Vacation about Sid. He was Sid’s hero, so I guess he felt a little bit guilty because Sid went down that road because he wanted to be like Johnny.”

Upon returning to the US, Thunders and family set up home in Dexter, Michigan. The guitarist hooked up with his teen idol, MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer, to form Gang War. But the project was doomed to failure.

Kramer: “Johnny was impossible to work with because he had another job that was more important. It’s the way heroin addiction works – you can’t do anything until you cop. I thought I could fix it. And of course I can’t fix anyone but Wayne. And I can hardly even fix Wayne by myself.”

It was at this point that Julie unexpectedly left with John Jnr, Vito and new-born baby Dino. Johnny would never see his children again.

By the early 80s, Thunders had hit an all- time low, haunting the New York streets, hawking licks for chump change, looking for a fix. “He was walking death,” says Aerosmith’s Joe Perry, who shared management with the New York Dolls in the early 70s. “Every time I ran into him he was desperately trying to get from hour to hour. You’d hear that he’d tried to clean up and then he’d be back living on the street again.”

Barry Jones: “I once got an earful from his mother when he’d told her his hand was infected. So I took him to Beth Israel, and they said if he hadn’t come in that night he’d have lost his hand. He’d missed, shooting Tuinal, and his hand had blown up like a crusty balloon… He told his mother he caught it in a cab door.”

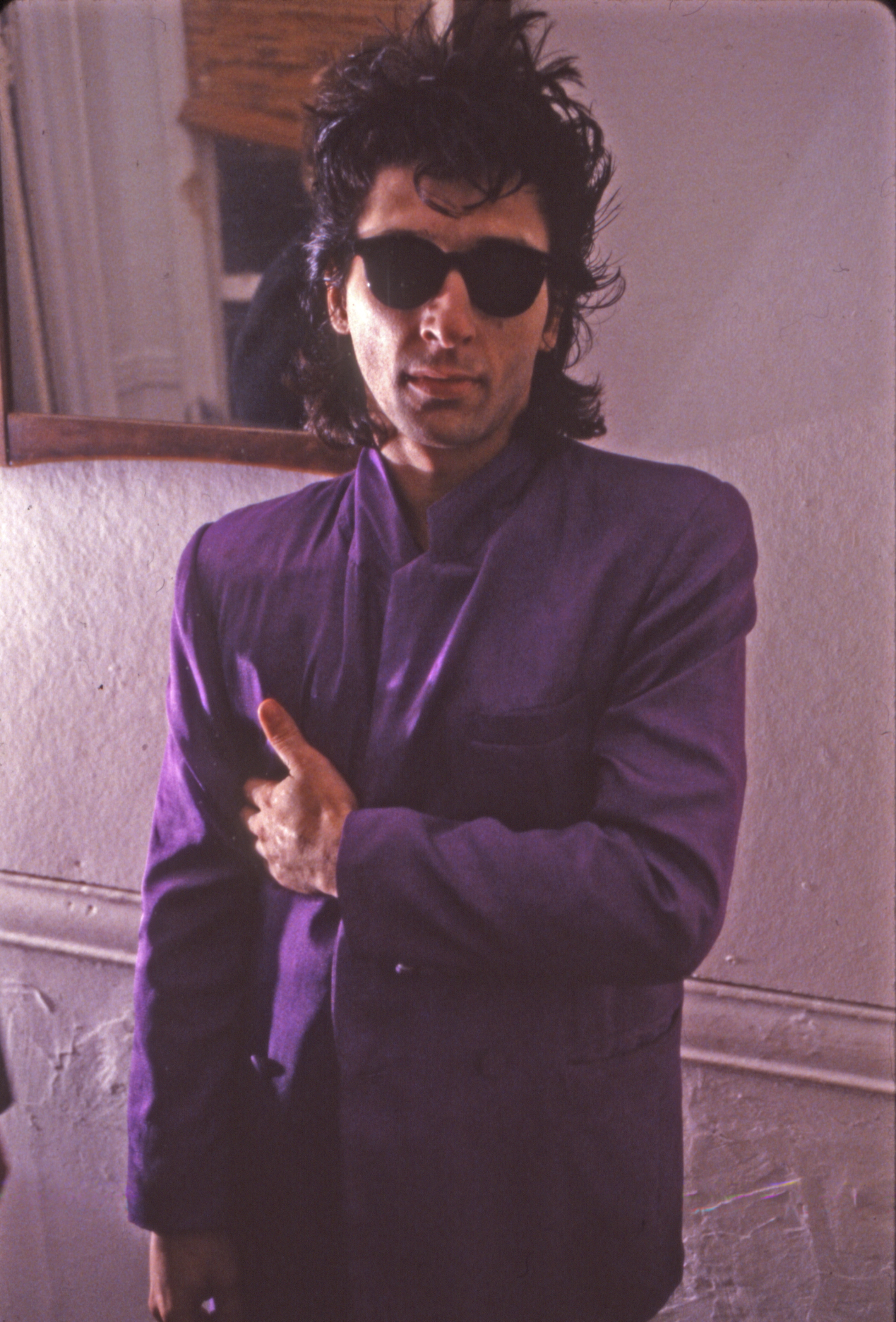

Enter Christopher Giercke, enigmatic German entrepreneur, producer of such films as Cocaine Cowboys, and latterly founder President of The Genghis Khan Polo And Riding Club, Kathmandu, who met Thunders at photographer Marcia Resnick’s New York loft in the spring of 1981.“He was bright, charming and quick-witted,” says Giercke. “Especially when he had his drugs of choice, which unfortunately for him, and everyone who cared for him, involved heroin. At that point he probably consumed two grams a day.”

Thunders, now reunited with Nolan, invited Giercke to watch him play at the Peppermint Lounge. But the gig was cancelled due to the fact that the band had pawned all of their instruments. “Of course, this was a rather pitiful period in his career,” Giercke deadpans, “And, optimistically, I told him that I could change his predicament.” Giercke offered Thunders a place to live below his loft, naively thinking the guitarist “just had to learn to take better drugs”. Thunders was unable to keep a band together, but Giercke could help find him gigs.

“He had Jerry Nolan and Walter Lure around, and they were comfortable to work as long as I handled the money,” says Giercke. “Johnny had the habit of collecting advances, not sharing them with the other players, and often not turning up when required. His continuing relationship with Jerry was important for the band but disastrous for me in my attempt to get Johnny away from heroin. Johnny would enjoy good wines, smoke and cocaine, but Jerry insisted on heroin.”

Thunders, it appeared, had finally found a father figure he could trust and depend on. But could he reciprocate in kind? It was doubtful that Johnny Thunders had it in him. But what of John Genzale? Could anyone reach the man behind the mask?

- The Only Ones: much more than one-song wonders

- Bluffers's Guide to the New York Dolls

- The 10 best Ramones songs, by Marky Ramone

- Johnny Thunders: Looking For Johnny

Susanne Blomqvist, a 20-year old Swedish hairdresser, first met Johnny Thunders in Stockholm after catching him playing a gig with Hanoi Rocks in 1983. The following night a mutual friend called her up and invited her to see Johnny play again. She accepted, and on arrival went backstage, where Thunders could manage only a somewhat bashful ‘Hello’.

“It was really cute,” says Susanne. “He was a very sweet man behind everything. I didn’t fall in love with him right away, but his shyness and vulnerability really touched me.” When it was time for Thunders to take to the stage, he ordered everyone except Susanne out of the dressing room. He then refused to perform unless Giercke persuaded her to come out on to the stage in her home town and be introduced to the audience by Johnny as his ‘Swedish wife’.

After nearly an hour, Susanne complied. “I was only 20, just a kid. Johnny was 30. We were two metres apart on that stage, and that’s pretty much how we stayed for the next seven years. He was a true gentleman with a good heart. He was into heavy drugs, and I knew that, but he didn’t want me to try anything. He protected me from that. He was also very romantic, with flowers and presents. He took me out to dinner and treated me as a princess. It was true love between us.”

Christopher Giercke, realising that the strictures imposed upon recovering heroin addicts in the US (Methadone doses were administered in the street to addicts by armed police officers) were demeaning and counter-productive, had already relocated Johnny to Paris. But after filming the lead in director Patrick Grandperret’s Mona Et Moi in the city, Johnny set up home with Susanne in Sweden.

After 10 years as the barely breathing embodiment of heroin chic, Johnny Thunders set about rebuilding his shattered life and re-establishing contact with the inner John Genzale that he’d suppressed for so long. Susanne Blomqvist: “He loved cooking, he was a true Italian. He loved spaghetti and tomato sauce, and making soups. He really enjoyed staying at home and reading his Herald Tribune. He was a very sensitive, intelligent man.”

“Johnny read a lot,” says Stevie Klasson, guitarist with Thunders’s final touring band, the Oddballs. “Autobiographies of Noriega and Howard Hughes. He’d always have books on politics and religion in his saddlebags. He was fascinated by a book about the Catholic church called In God’s Name [by David A Yallop].”

“Johnny was really Catholic,” says Susanne. “He didn’t want me to have too-short skirts and show too much skin. I know he was praying, and many times he made the sign of the cross. We went to many different Catholic churches. He wanted our daughter raised as a true Catholic, she was baptised as a Catholic. He went to confession when he was younger, and it wouldn’t have surprised me if he still did that and didn’t tell anybody.”

By 1986, Christopher Giercke’s role was diminishing as Johnny gradually regained control of his life and career (having released the acoustic Hurt Me album and its return-to-form, all-guns-blazing follow-up Que Sera Sera in rapid succession). He had finally re-established contact with his mother and sister, but had still heard absolutely nothing from Julie concerning the state of health and whereabouts of their two young sons, Vito and Dino. Johnny knew the pain of an absentee father, and feared his sons would consider his enforced absence from their lives as cold rejection.

Susanne: “He missed his kids. It was hurting him so much. He didn’t know where they were but he was thinking of them every day. I think he got a lot of his sorrow and anger out when playing music.” Returning to the road may have been therapeutic, but slipping back into the skin of obnoxious, junkie wastrel Thunders was becoming an increasingly painful process. Susanne Blomqvist: “He hated going on the road. He just wanted to stay home, read his books and watch films.”

Now finally weaned from heroin to Methadone, John would have to metamorphose into his stage persona by other means. “We were on the train to the gig,” Oddballs vocalist Alison Gordy remembers. “Johnny’s playing cards with Stevie, and he starts becoming Johnny Thunders. He started twitching. I went over and said: ‘Johnny! You’re becoming him.’ He said: ‘Yeah.’ He didn’t do any drugs, but I could see a physical change coming over him. It was an interesting transformation; suddenly he was all jazzed up.”

Some sections of his audience didn’t want to see Thunders clean, they’d come to see the mythic smack zombie of legend. “It was so sad sometimes when Johnny was in great shape and you could see these vultures’ disappointment,” says Stevie Klasson. “They’d be calling out for Junkie Business and throwing loaded syringes on stage. Johnny Thunders was sick and tired of being Johnny Thunders. He wanted to be an entertainer and have a great band.”

Thunders, determined to give the kids exactly what they wanted, even started to fake it. Glen Matlock: “I remember seeing him backstage at the 100 Club. We had a chat and then he said: ‘We’re going on now,’ so I went out the front. And in the minute it took him to walk to the stage, he went from being completely compos mentis to falling over. It was like an act.”

“He would absolutely do that,” confirms Gail Higgins, “That little stumble as he walked on stage was a definite put-on. He knew what they wanted. At the end he’d say: ‘They’ve come to see me die.’ Which must have been sad for him.” Susanne Blomqvist: “I can remember him winking at me from the stage to say: ‘I’m okay, even if I’m acting fucked-up,’ Maybe I’m taking his pants off here… maybe people will be disappointed, but he really wasn’t that fucked-up on stage.”

Johnny was suddenly so together he was even offering wise counsel to others. Stevie Klasson: “He was very protective, especially when it came to drugs. He didn’t want me to make the same mistakes that he had done. I asked him early on for some smack and he gave me a smack in the mouth.”

Peter Perrett: “In the 80s, Johnny would come around and tell me I was wasting my talent.”

Johnny Thunders’s transformation from burned-out casualty to rehabilitated contender, appeared to culminate with the birth of Jamie Genzale in 1987, just as work was being completed on Copy Cats, a collaborative collection of formative covers with Patti Palladin that represented the finest, most complete body of work to bear the Thunders name since So Alone.

As he returned to Sweden for the birth, it seemed that Johnny was finally in a position to be a real father at last; to break the cycle of parental abandonment that had dogged and defined his entire life. But, deep down, something was wrong. Susanne Blomqvist: “When Jamie was born I could feel that he didn’t want to get too close to her. He was very proud, and he took care of her, but at the same time I could see that he was scared to be a parent again… scared of hurting her. He couldn’t stand the thought that we weren’t going to get old together, as a family. He didn’t want to repeat the same thing his father did to him.”

If Thunders’s reticence to commit might have seemed irrational, his next move was inexplicable. Until you realise he was harbouring a dark secret. Not long after Jamie’s birth, Johnny Thunders had been diagnosed with leukaemia. Susanne Blomqvist: “We separated when Jamie was one-and-a-half years old, and he moved back to New York. I drove him out to the airport, we said goodbye, and I knew I was never going to see him again. He went to see a doctor once and they took some tests, and something changed. I said: ‘Something is not okay with you.’ He said: ‘Oh, it was okay, it was nothing.’

“But then he started behaving in a way that made him unbearable to have around. He wasn’t hurting me or anything like that, he just wasn’t the homey guy any more – the guy who wants to cook the chicken soup, or go and rent a film… He was showing me less and less of John, and resorting to Johnny Thunders. That must have been very painful for him, because he didn’t want to be Johnny Thunders, he wanted to be the father, the husband, the good friend, the best friend, but to stand the pain he had to choose that role. He knew something that I didn’t know, that nobody knew: that he wouldn’t live too long. That’s how protective he was over me and Jamie. He was saving us. I think of him every day and I miss him every single day. He’s still in my heart. I’m so grateful that we had those years together and we had beautiful Jamie. I never saw John as Johnny Thunders. For me he was John. John Genzale. And nobody else.”

Thunders returned to the road with a vengeance in the last year of his life. In the spring of ’91, following lucrative gigs in Japan, he ended up in New Orleans intent on fulfilling his ultimate musical ambition.

“The plan was to hire Sea-Saint studios,” says Stevie Klasson, “get Jerry Nolan back on the drum stool, and fly Alison Gordy down once we’d settled in. Johnny was hoping to rope Dr John and John Campbell into the equation. For years it was Johnny’s big dream to record a New Orleans record.”

But Thunders never got to record his New Orleans record. He was found dead in room 37 of St. Peter House, New Orleans on the afternoon of April 23, 1991. He was 38 years old. The exact circumstances of his death remain inconclusive and the subject of much conjecture. But it seems his leukaemia-weakened body went into seizure on the night of the 22nd, and his new-found companions, possibly convinced they’d either supplied him with the chemical high that had killed him or who were holding enough chemicals to make it appear that this was the case when the cops came calling, simply left him to die.

Thunders’s body was taken back to New York for his funeral. The presence at the service of 13-year-old Vito Genzale – Thunders’s son from his first marriage, formerly known as The Sprog – almost stopped Lee Black Childers’s heart; the resemblance was so strong. Vito and his brother Dino hadn’t been told who their father was. Alison Gordy took Vito aside, sat him down and told him: “You’re going to hear a lot about your father, but don’t believe everything you hear, because I want you to know that he was a really funny, smart, great person.”

Jerry Nolan was hit hard by Thunders’s death. “I answered the phone and this guy’s crying, and it’s Jerry,” says Steve Dior. “And I’m like: ‘Oh my god, Jerry’s crying.’ And he doesn’t cry. He’s bawling his head off worrying that Johnny didn’t know how much he loved him.”

Nolan died following a massive stroke brought on by bacterial pneumonia and meningitis on January 14, 1992, less than a year after Thunders. Susanne Blomqvist: “They were like an old couple who’d been married for a hundred years. It was like they couldn’t live with or without one other. Jerry took a big responsibility for Johnny, and I believe that deep down Jerry missed Johnny so much that he died within the year.”

When Thunders died, Nolan asked the guitarist’s sister, Mariann Bracken, that if anything happened to him could he be buried next to Johnny. Today the pair occupy adjacent plots in St. Mary’s Cemetery, Queens.“You had to separate Johnny Thunders from the real Johnny, says Billy Rath.

“Underneath that veneer was a loving father, a loving man and a good guy to be with. He was a very lonely person because of carrying that persona and losing everybody he held dear. That song So Alone fits him so well. He felt very alone.”

So what became of The Sprog? Abandoned in infancy, his ultimate legacy would appear to be a similarly troubled soul to that of his father. On discovering that he was the estranged son of Johnny Thunders, Vito Genzale tried to live up to his legend. On the 17th of last month he made parole from Sing Sing Correctional Facility after serving four-and-a-half years for criminal sale of a controlled substance.