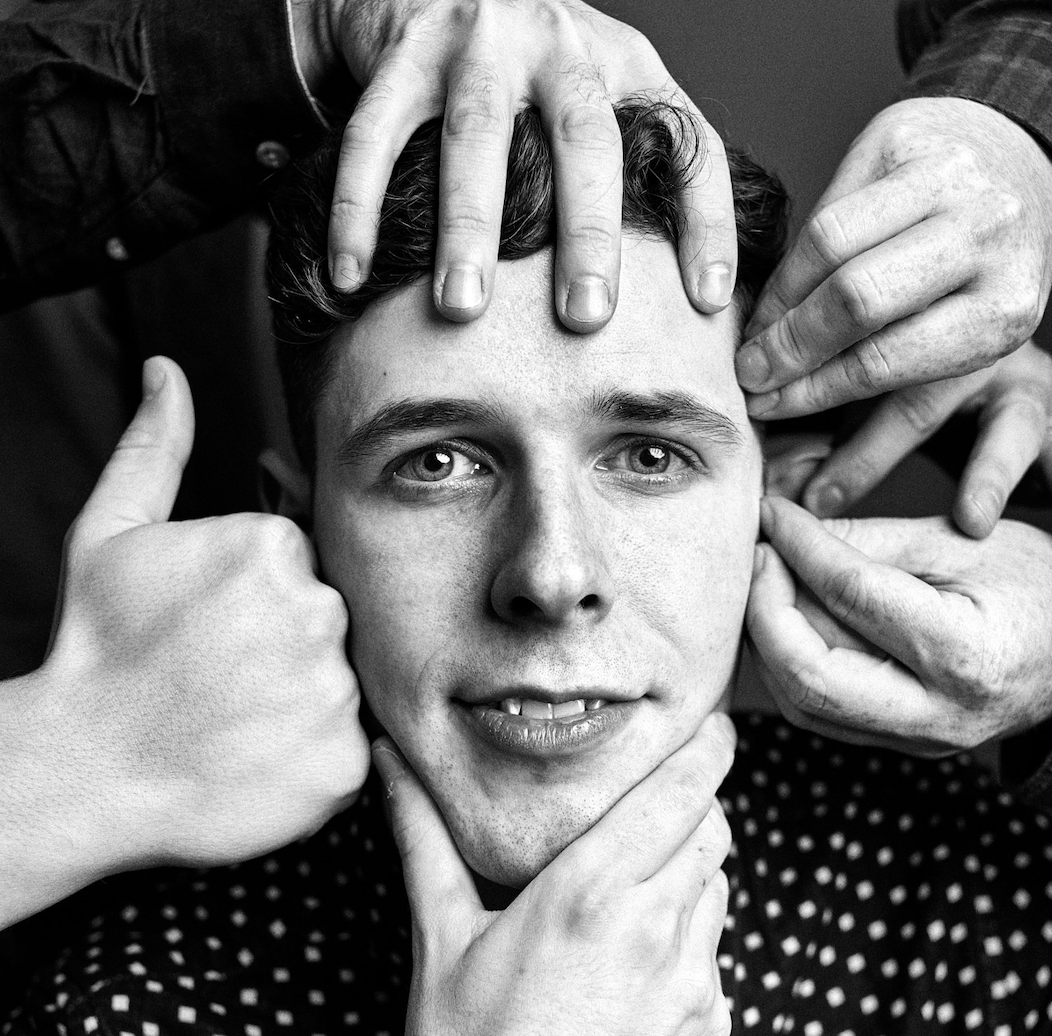

Soen drummer Martin Lopez is in a refreshingly honest and upfront mood. He speaks his mind, and, just like his band’s music, isn’t afraid to dip into deeper, darker places.

“We have to keep things special,” he says about the future of the band. “I lost that a few years ago. It was the saddest moment of my life, when I realised everything I dreamed of and worked so hard for, to be a musician and to tour and make a living from music… somewhere along the line I just felt like, ‘This is shit – I’m just doing this because I need to pay the rent.’ Somewhere I got brokenhearted. A few of us have felt that, so we’re really trying to take the right steps with Soen so that we keep our love for the band alive.”

Lopez, who juxtaposed grace with brutality in Opeth for just shy of a decade during their Blackwater Park and Deliverance years, is opening up not long after the release of the prog metallers’ latest album, Lykaia.

It’s their third record in five years, but they have been wary of overexposure and things becoming just a little too routine. So, they have been selective with the live shows they perform, deciding instead to keep things organic by easing off the accelerator pedal.

Lykaia, a result of this considered approach, is an engrossing album that’s not only bulging with adventurous metal chops and velvet melodies reminiscent of Lopez’s old buddies Opeth, but also full of overarching melancholy and grainy, crepuscular musings, too.

Not so cheery either is the record’s title, which is named after an ancient Greek festival on Mount Lykaion that was full of bloodthirsty themes of cannibalism and human sacrifice, while the album’s artwork plays on the event’s sinister link with wolves.

“When we were recording, we were talking a little bit about the meaning or relation man has to wolves, and what it says to us, in folklore,” says singer Joel Ekelöf, who is also speaking down the phone from Stockholm in Sweden. “We also wanted something that was a bit more vile and fleshy for this album, rather than smart.”

Soen, which also features bassist Stefan Stenberg, guitarist Marcus Jidell and keyboard player Lars Åhlund, drew comparisons to Tool when they unleashed their shapeshifting debut effort Cognitive in 2012, with the follow-up Tellurian expanding the sound two years later.

The group made a conscious decision to dial down the digitalisation on Lykaia, with a new emphasis on analogue equipment used to conjure a more natural, personal aura. It seems to have paid off.

“We feel a little bit of that is lost today in modern metal music,” Ekelöf says. “People are in post-editing using digital effects too much. We wanted to go in the other direction, trying to leave the human in it.”

Lopez admits that Soen got “carried away” on their first two records and saw some of their identity seep away as they strove for studio perfection.

“You can hear that when things are too perfect, the actual soul of the band disappears,” Lopez continues. “It’s impossible to be a perfect musician, and music you write is basically emotional music – straight from the heart. So when you try to take all that and pass it through a filter of a computer, it just comes out as manufactured.”

Soen first started recording in 2010 after Lopez – who had been collating an arsenal of riffs, melodies and beats since his departure from Opeth in the mid-2000s – met Ekelöf, the “right guy” to help bring the drummer’s plentiful ideas to life.

The duo remain the core of the group, writing the earthy foundations of all of Soen’s music, although recent recruits Jidell and Åhlund also provided some input on Lykaia.

For Lopez, however, stepping into the studio wasn’t something he was particularly overjoyed about this time around – but then again, it never really is for the Swede.

“I love writing music, and I love doing the demos for an album, but somewhere along the line it just becomes too much music, and it takes over your life completely,” he says. “All the pleasant constructive discussions that you have with your band members after a few months turn into just discussions. I want to play with people who really stand up for what they believe in, but it’s really intense.”

“We do have very high ambitions when we record albums and we are not ashamed to be almost perfectionistic in the way that we want our music to sound,” Ekelöf adds.

Soen’s output does, at times, feel like the sum of a number of parts, with Lykaia’s rousing opener Sectarian featuring guitar work that could have been crafted by the wizard-hands of Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt, while there still remain some Tool nods.

Lopez, however, is bullish about the similarities. “For me, Tool is one of my favourite bands of all time, so to be compared to them is really flattering,” he says.

And Opeth? “That’s another of my favourite all-time bands,” he smiles. “It’s also quite understandable. I started playing in Opeth when I was 18 or something, and played with them for 10 years. We played the music that I loved, and I was very involved in Opeth. Now when I have my band, I’m not going to avoid doing the music that I like because it might sound like the band I played with before.”

Prog fans who aren’t familiar with Soen should get their kicks from the dextrous intricacy of the brooding riffs, the enveloping atmosphere and the multi-layered textures. Don’t expect overt flamboyance though, as the band are distanced from the fretboard gymnastics associated with the Dream Theaters of prog.

“We love all the old progressive bands, and I think we have always been writing music in a way where there are journeys or adventures through the songs,” Ekelöf says. “You experience things, and we play a lot with dynamics. But I think there’s another aspect of progressive metal where everything is perfect and technical. We feel that we don’t relate much to that.”

“I really like the word progressive,” ruminates Lopez. “It stands for opening new doors and experimenting. That lands well with what we do.”

Soen were slapped with the supergroup tag when they formed, with Ekelöf also of Swedish outfit Willowtree and original bassist Steve DiGiorgio having played with metal overlords Testament and Death.

For Lopez and Ekelöf, however, that label – often associated with acts that only release one or two records before dissolving – isn’t one that sits kindly with them. This isn’t a short-term fix.

“From the beginning, there was a lot of talk about a supergroup, and we understand people saying that,” Ekelöf says. “But for Martin and I, it was something that we were in for the long run. It was never a project for us.”

“Once you join a band, you kind of give everything you have to it,” Lopez adds. “You can’t do it just for a year, to release an album – at least I don’t work that way. For us it’s the only band that we have, and the only band we planned to have. We want to have a long career.”

The two musicians are speaking before they hit the rehearsal studio to ready themselves for European shows in March and April. After that though, the tour schedule goes blank.

Soen don’t accept all the bookings they are offered – something they readily admit negatively affects their bank balance – in the hope of keeping things stimulating.

“Everyone in the band has had long careers in music, and we agreed that as soon as the touring gets extensive and there are too many shows, it just turns into work, like working in a factory, and that removes most of the joy of being a musician and the love of what you do,” Lopez says.

“For us, playing live is such as an amazing feeling,” he continues. “It’s a cliché, but it’s like a drug. You feel in a way that nothing non-chemical can make you feel like. We try to keep that alive. We don’t want to lose that, and it does hurt us economically to tour as little as we do, but we are very, very happy with the choice that we made.”

“We want to be able to give 100 per cent every show,” Ekelöf adds. “It’s quite important for us that we don’t play under the influence, because we want to be very professional on stage, and we always play everything live. We don’t do any backing tracks, because I feel that some bands are taking the easy way out by putting choirs on backing tracks, putting some string or key arrangements to make it easier. We rehearse everything. We do the harmonies live, we do everything live. That’s what it’s supposed to be about. You’re supposed to be a band which is burning 100 per cent and everything you hear should be performed in that very second, that very moment. It’s about creating magic.”