Which is better: Son House's Death Letter or The White Stripes version?

A heartbreaking story of love and loss written in 1930 by ex-convict Son House, Death Letter was covered by alternative scenesters The White Stripes. But who did it best?

Almost a full century separates the birth of the Mississippi Delta titan, who mentored both Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson, from the release of the electrifying reinterpretation of his most powerful and haunting song which introduced it – and him – to a generation unborn when he died. To be precise, 98 years elapsed between the arrival of Son House (second only to Charley Patton as the human foundation-stone of classic Delta blues) near Clarksdale in 1902, and the release of Detroit duo The White Stripes’ punk-blues version of his epic Death Letter as part of their second album De Stijl in 2000.

In May 1930, Charley Patton drove there from his Delta home-base for a marathon recording session commissioned by Paramount Records. With him were his buddy Willie Brown – yep, the same Willie Brown name-checked by Robert Johnson in Crossroad Blues – his piano-player girlfriend Louise Johnson, and a tall, skinny ex-con named Eddie House, better known as ‘Son’.

Son House had taken up the guitar but a few years before, and he was only recently back in the world after serving two years of what had originally been a 15-year sentence in the Parchman Farm state penitentiary for shooting a man in a bar-room brawl. The situation was complicated somewhat by a developing attraction between House and Louise Johnson, but it was still impressively productive: Brown and Johnson cut two songs each, Patton four and Son himself no fewer than seven: six of which were released as singles and the seventh (a version of Walkin’ Blues) remained unheard for decades.

The single which concerns us was the two-part My Black Mama. Virtually every verse of the A-side recurs in subsequent compositions by others: you’ll hear familiar lines from Albert King’s Oh Pretty Woman, John Lee Hooker’s Burnin’ Hell and Kokomo Arnold’s Milk Cow Blues. the latter was subsequently adapted by Robert Johnson, Elvis Presley and the Kinks, to name but three. And, of course, Son’s slide-guitar riff was endlessly recycled by Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and, oooohh, everybody.

- Muddy Waters: Life After Chess

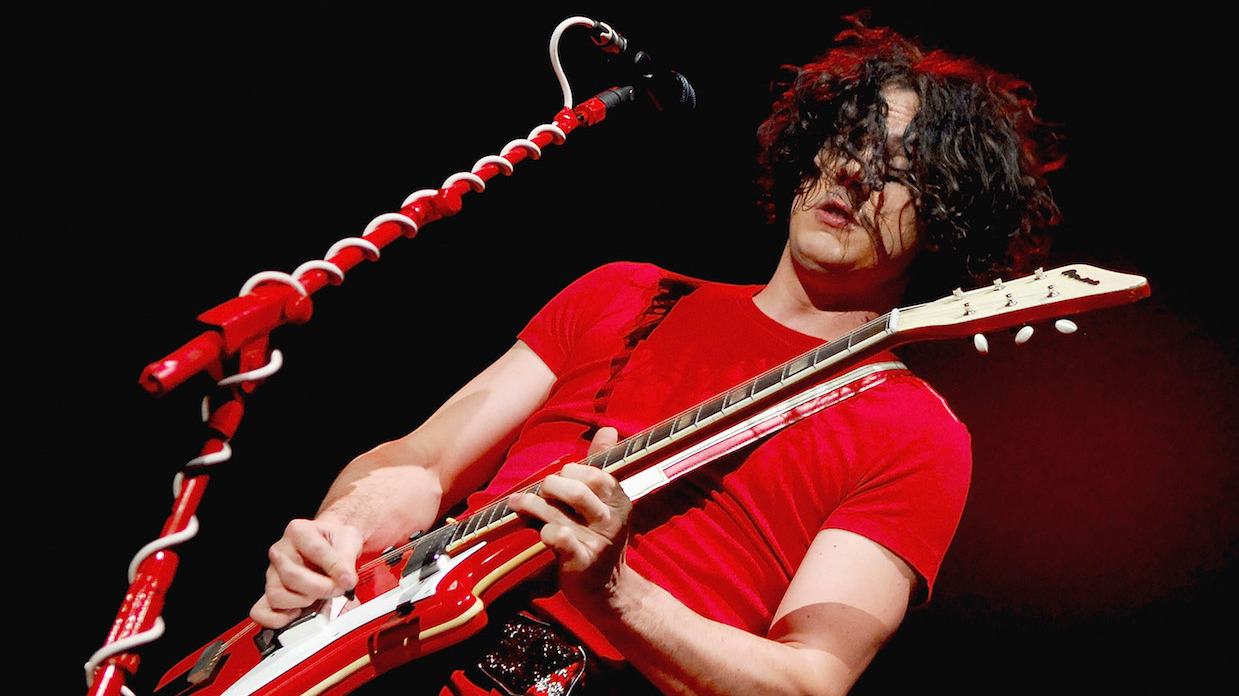

- Buyer's Guide: Jack White

- Bob Dylan goes electric, and the world changes

- John Lee Hooker Buyer's Guide

For his trouble, House received the princely sum of $40. Scratchy copies of those three Paramount singles later became collectors’ gold, but Son went back to playing Delta juke joints, driving a tractor and oscillating between the blues life and the church he’d so scornfully excoriated on Preachin’ The Blues. A dozen years later, Alan Lomax swung through the south on one of his legendary musical treasure hunts and recorded Son at home on behalf of the Library Of Congress: in 1941 with a string band featuring Willie Brown, and again the following year, this time solo. No money changed hands, but Son received a few bottles of Coca-Cola.

And that – barring a few local shows with Brown until the latter’s death in 1957, after which Son retired, seemingly for good – was it for Son House’s musical career until 1964, when he was tracked down by a posse of blues collectors led by Dick Waterman in Rochester, New York, where he was working as a railroad porter and barbecue chef. The folk revival was at its Newport Festivals peak, bringing with it renewed interest in semi-mythic Delta bluesmen such as Skip James and House himself. Enter John Hammond, who speedily signed Son to Columbia and brought him to New York City to record an album, released the following year as Father Of The Delta Blues – a title to which he had a stronger claim than any man living.

Now: Son hadn’t performed for years. He owned no copies of the records he’d made 35 years before, and probably hadn’t heard them since he cut them. In fact, he could barely remember his old songs. Fortunately, there was a man who could: a young collector and musician named Alan Wilson, soon to become co-leader of Canned Heat. Wilson not only had all Son House’s records, but he’d analysed them down to the last slide stroke and learnt them all off by heart. So he patiently re-taught Son all his old music, and sat at his side through the sessions, coaching him and occasionally backing him on mouth harp and second guitar. The resulting album was a triumph.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The revitalised and relaunched Son House was a smash at the next Newport Folk Festival, and even at Carnegie Hall. For the next decade, he toured the US and Europe, and a few live recordings were released before his health began to fail and he retired again, this time to Detroit, where he was cared for by relatives until his death in 1988.

Along with the a cappella gospel piece John The Revelator, Death Letter became not merely Son’s signature song for his 60s-era audience, but a solid blues standard. As such it was both much-loved and much-covered. Some who essayed it, like Tony McPhee, simply attempted to reproduce Son’s own performance in their own way. Some attempted radical revisions, such as the smoky, sultry, sophisticated jazz melancholy of Cassandra Wilson, the gruff funk of James Blood Ulmer or the Grand Guignol Phantom Of The Opera reading it received from the magnificent Diamanda Galas, or even the wonderfully daffy lyrical spin captain Beefheart gave it in Ah Feel Like Ahcid. Some, like the Grateful Dead, simply trainwrecked it (and if you’ve never heard it, I envy you). Most have their merits… but it took the oddball duo from Detroit to finally nail it.

Nothing about The White Stripes should have worked, but it all did. Strip away the cute, clever trappings – the ‘are- they-or-aren’t-they’ ambiguity, the rigorously applied colour scheme, the peppermint fetish – and what remains is that barebones punk take on archetypal Americana: Jack and Meg’s ability to leave so much out (bass being merely the most obvious) because they knew, so exactly and precisely, what needed to stay in. Not for nothing did they dedicate their debut to Son House (and include John The Revelator), and the second album, De Stijl, was where they went for the big one and cut Death Letter.

So: who wins? Despite the excellence of the stripes’ version, it’s essentially no contest. What Jack and Meg did is both intensely powerful and deeply honourable, and served up with a side dish of real magic. However, Death Letter belongs to one man, and one man only. It’s Son’s song, and will remain so always and forever.

Charles Shaar Murray is the award-winning author of Crosstown Traffic: Jimi Hendrix And Post-war Pop, and Boogie Man: The Adventures of John Lee Hooker in the American Twentieth Century. The first two decades of his journalism, criticism and vulgar abuse have been collected in Shots From The Hip. A founding contributor to Q and Mojo magazines, his work has appeared in newspapers like The Guardian, The Observer, The Independent, The Independent on Sunday, Evening Standard, and magazines including Word, Vogue, MacUser, Guitarist, Prospect and New Statesman.