It was, by any measure, one hell of an introduction.

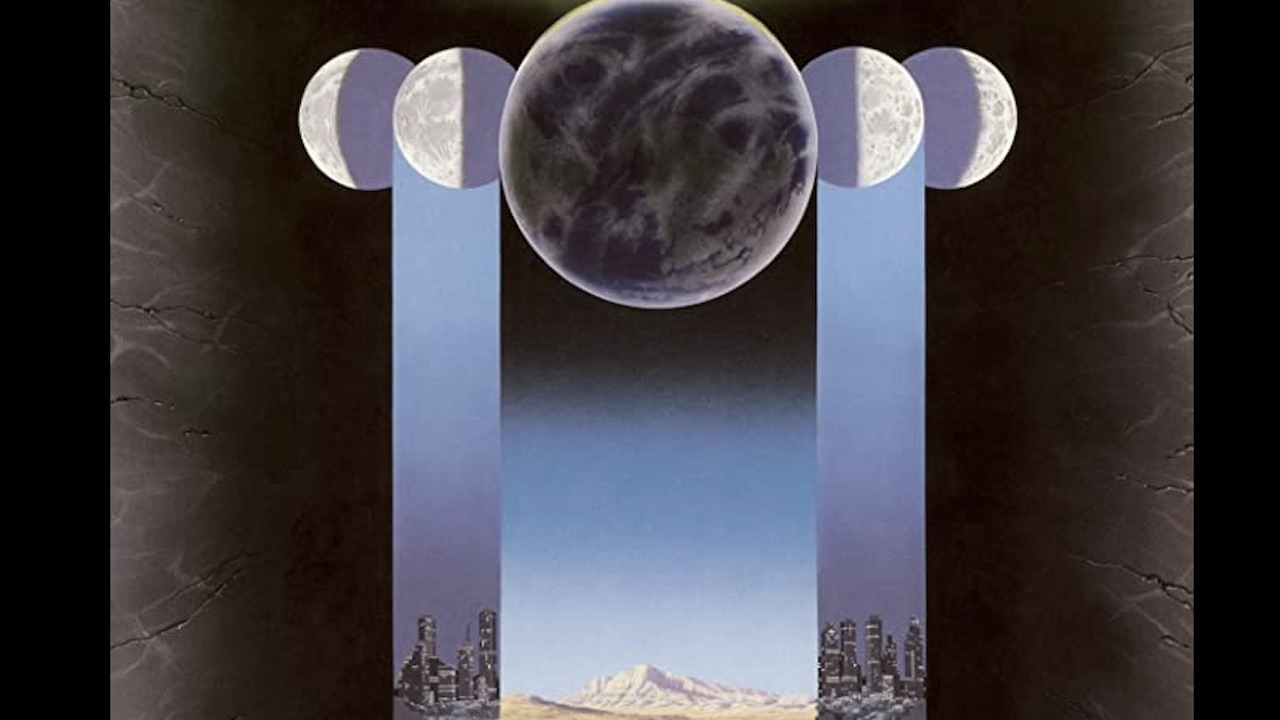

‘Houston Heavies King’s X Usher In A New Age Of Metal’ proclaimed the February 20, 1988 cover of Kerrang! A bold claim, made all the more intriguing for readers of the magazine by the fact that the Texan trio's debut album, Out Of The Silent Planet, was still one month away from release.

“I was shit scared!” the band’s bass-playing frontman dUg Pinnick readily admits. “It was super cool, and an incredible moment for us to see ourselves on the cover of an international magazine, but man, talk about being thrown in at the deep end! No-one knew who the hell we were, and suddenly we’re the future of metal? That’s a lot to live up to!”

In February ’88, dUg - then plain ‘Doug’ - Pinnick was 37-years-old, no spring chicken in an industry obsessed by youth and the relentless churn for the latest Next Big Thing. He and his bandmates, guitarist Ty Tabor and drummer Jerry Gaskill, had been playing together for eight years and were wholly accustomed to facing rejection, apathy and false promises. Hype? Opportunity? Adoration? These were alien concepts to the trio. Little wonder they felt apprehensive and confused.

“It simply did not compute,” Ty Tabor admits. “This was not our world.”

“It was like looking out at the ocean and seeing a tidal wave incoming,” says Pinnick. “We had no idea what to do. So it seemed like the best plan might be to just dive in head-first.”

King's X's frontman has no strong recollections of the first time he and his bandmates of almost 40 years jammed. Guitarist Ty Tabor does. He remembers the session in the kitchen of Pinnick’s two-bedroom home in Springfield, Missouri feeling “magical”.

“I was very excited,” he says. “I had this instant recognition that this could be great. I’d never had that experience where I instantly thought, Wow, this a different level.”

Before there was King’s X, dues were paid, as The Edge (1980-1983) and Sneak Preview (1983-1987). The Edge were a bar band who sneaked original material into their five sets a night bookings when there were less paying patrons than people on-stage: the best of these originals were later exhumed and re-recorded for the 2003 King’s X album Black Like Sunday. The New Wave-influenced Sneak Preview made a self-titled album of their own in 1983, and struggled to give away the 1000 copies they pressed up.

“But we persevered,” says Tabor. “We believed that we had further to go musically. We were hard-headed about the idea that we could, potentially, be very good.”

In 1985, Sneak Preview were made an offer by Star Song, a Christian record label operating out of Houston, Texas. Star Song were developing a young singer from Louisiana named Morgan Cryar, and wanted to recruit the trio as his backing band for one year, dangling a weekly wage, rent-free apartments and the opportunity to write for their promising new protégé.

Though Pinnick, Tabor and Gaskill all held Christian beliefs, they were wary of being drawn into the insular Christian rock scene. Back when they played as The Edge, Pinnick, who identified as gay, was urged by a Christian manager to attend a conversion camp: a fellow musician informed him he could no longer be a room-mate as “God told him he couldn’t sleep in the same house” as the bassist. For Pinnick, the scene’s hypocrisy rankled.

“There were bands in the Christian scene who were all holier-than-thou, and then you’d go backstage and they were all fucking chicks and drinking!” he recalls. “I didn’t want to be a part of that shit.”

Nevertheless, the trio took up Star Song’s offer. “We were starving,” says Pinnick, who, with Tabor, ended up contributing to the writing of Cryar’s 1986 album, Fuel On The Fire. “I felt like a whore,” the guitarist admits. An engagement backing Cryar at a huge Christian music festival, broadcast to over two million people worldwide, and remembered by Tabor as “one of the most disgustingly horrible experiences of my entire life”, would prove to be the last straw.

“That’s the day I woke up and realised that Jesus was for sale, and people were making a lot of fucking money doing it,” Pinnick told King’s X biographer Greg Prato. “It scared me. I got a glimpse of how Jesus must have felt when he went into the temple to do his sacrifice, and there were all these people out there selling shit.”

On the flight back to Houston, the trio collectively decided that their relationship with Cryar was over. As they talked about their band’s future, they played one another demos they’d been recording individually. Tabor offered up a composition named Pleiades he’d co-written with friends in a ‘drop D’ tuning and remembers his bandmates “freaking out” over its juxtaposition of ethereal vocal harmonies overlaid atop a crushingly heavy guitar riff.

“I didn’t expect them to like it,” the guitarist admits. “When I wrote it I wasn’t thinking, This is our new sound. But that song was my own personal ‘Eureka!’ moment, where I’d thought, I’m going to write whatever I feel, and not care whether people like it, I’m going to follow my soul. I was actually kinda afraid to let Dug and Jerry hear it, because I thought they might think it was nonsense. But they liked it. They were like, ‘This is who this band is. This is what we need to be doing’.”

“That moment changed the way I saw music,” admits Pinnick. “I didn’t realise that tuning was special or unique, I just liked it, and got inspired. I went home, tuned my bass E string down to D, and wrote half our first record.”

In the summer of 1986, the newly-invigorated trio met a local music industry figure who would transform their lives.

Sam Taylor was ZZ Top manager Bill Ham’s right-hand man, and a musician and producer in his own right. Introduced to the band by mutual contacts at Star Song, Taylor came home from his first meeting with Sneak Preview and informed his wife that he’d found the next Beatles. From that day, he exerted a dominant controlling influence over the band, effectively installing himself as a de facto fourth member.

He suggested a name change, to King’s X, the name of a group his own brother had played with in the 1960s. He rented the band a practice space in down town Houston and presided over 12 hour daily rehearsal sessions, tweaking and polishing their song arrangements, fine-tuning their vocal harmonies, encouraging the trio to celebrate their faith and beliefs in the lyrics. He then booked the trio studio time to record a demo with Led Zeppelin engineer Andy Johns and began telling music business acquaintances that he’d discovered the hottest new band in America. No-one bit.

“Sam sent out our demo to everyone… and we got rejected by everyone he sent it to!” laughs Pinnick. “I can’t say that I was disheartened, I was used to rejection. Plus we knew we were getting better, even if no-one else did.”

Finally, King’s X caught a break. When Marsha Zazula, co-founder of Megaforce Records with her husband Jon, popped the band’s cassette into her car stereo she thought she was listening to new music recorded by an acquaintance called Steven Taylor, as it arrived in an envelope from ‘S. Taylor’. Though it wasn’t what she was expecting, Zazula fell in love with the songs, and demanded that Megaforce sign the band.

Her husband, a New Jersey record store owner who’d launched the label in 1982 to release the debut album by a young Californian band named Metallica, was far from convinced. But having made its reputation championing the emerging Thrash metal scene – other early signings included Anthrax, Overkill and Canada’s Exciter – Megaforce had recently signed a partnership deal with major label Atlantic and were looking to diversify, with former Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley a recent addition to their roster. King’s X were booked to play the launch party for Frehley’s Megaforce debut, Frehley’s Comet, at the Cat Club in New York City.

The trio remember the gig as a total disaster - “a train wreck” says Tabor - but Jon Zazula came into their dressing room post-show and insisted that the trio could not leave the city until their inky signatures were dry on a Megaforce contract.

“Finally our little fish was in the big ocean,” says Pinnick. “We knew this was where the real work started.”

Asked for his memories of making King’s X’s debut album, dUg Pinnick’s answer comes instantaneously: “I hated every moment of it,” he says.

“Sam Taylor was a very particular, hard-driving person, and he made us work so fucking hard. You know those movie where the coach of the basketball team is a mean bastard and hated by everyone, but he gets the team to win? That’s what Sam was to me.”

“Making a record is stressful,” says Jerry Gaskill, “because everything is under the microscope. Every day was like going from hell to heaven! But we were excited to be actually making a record. For the longest time we were resigned to the idea that we’d never be more than a local act, but we believed in the music and we believed in ourselves and we gave everything to it.”

“I remember being a little bit scared and nervous,” says Ty Tabor. “We didn’t know if the label was going to hate it. But I remember when we finally put a sequence of the songs together, and listened back to it like an album, we were all taken aback at how great it sounded. I remember thinking, Wow, I don’t recognise this band as us, but I really like it. We had never heard ourselves sound like that, never heard the full picture. I thought, Wow, I hope people get this.”

Out Of The Silent Planet, its title taken from the name of a book by British writer and theologian C.S. Lewis, sounded like nothing else around when it emerged in March 1988. Seeking to unpick the band’s heavy, dark, emotional sound, music critics made comparisons to The Beatles (vocal harmonies), Metallica (riffs), Rush (arrangements), The Police (dynamics) and U2 (spirituality), influences which Dug Pinnick readily cops to. “All those and more,” he says. “You could add in Jimi Hendrix and Sly & The Family Stone too for starters.”

From ethereal trippy opener In The New Age to hypnotic album closer Visions, via the uplifting Power Of Love, sublime ballad Goldilox, the new dawn-embracing King and the sheer euphoria of Shot Of Love, Out Of The Silent Planet signposted the arrival of a major new talent.

The UK music press predicted that the trio, alongside the likes of Faith No More, Voivod, Masters Of Reality, Living Colour and The Big F, were going to change the face of hard rock and metal. The band’s peers raved just as hard as smitten music writers, with members of Pantera, Pearl Jam, Alice In Chains, Winger and more lauding the album.

“It was really moving and heavy and dark and uplifting – it was everything,” states Anthrax guitarist Scott Ian in Greg Prato’s King’s X: The Oral History. “They were on Megaforce and Atlantic, and if you put me behind one of those desks, I’m saying, ‘This band is the next U2. This record is The Joshua Tree – that’s where we need to go with this.”

“That kind of praise was shocking, surprising, exciting, exhilarating,” says dUg Pinnick. “What more could you ask for than to have your peers saying all these amazing things? It was pretty overwhelming. I don’t know if human beings are even supposed to experience that kind of praise because it knocks you every which way.”

In November ’88, King’s X came to London to make their European live debut at the fabled Marquee Club. It’s a gig of which all three musicians have vivid memories.

“I’d always wanted to go to England, all of us did, because that was the home of The Beatles,” says Pinnick. “I was so nervous, sitting backstage, thinking that Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin and all my heroes had sat right here. I found out later that it wasn’t the same place, because the club had moved from those days, but at the time it was overwhelming. Then I ate some fish and chips for the first time and it was horrible, so greasy, so that made me feel even worse!”

“I didn’t think anybody was going to show up. We’d been playing to five or six people on tour all over the United States so I was thinking maybe there’d be five people out there at best. And then we walked on-stage and the place was sold out and people were jumping up and down and singing every word. We couldn’t believe it. I thought, Wow, this is cool! This was what I’d been searching for, this shared euphoria. I was instantly addicted.”

“It was like, Oh wow, we’re going to be as big as The Beatles!” laughs Jerry Gaskill. “But of course that didn’t happen...”

Unlike Guns N‘ Roses, who were able to parlay their early rave reviews from the UK into support from MTV and radio stations on home turf, King’s X discovered that the buzz around their band in Britain meant less than nothing in America. Though tours with Blue Oyster Cult and Cheap Trick boosted their profile, and Atlantic bankrolled glossy videos for King and Shot Of Love, Out Of The Silent Planet peaked at Number 144 on the Billboard 200.

Still, they had one remaining ace up their sleeve, the gorgeous, shimmering Goldilox, a tale of unrequited love with lyrics penned by Ty Tabor after spotting a beautiful girl in a Houston club named Cardi’s. This, everyone who heard the band’s debut album agreed, was the record’s hit single. But, in what appeared to be an extraordinary act of self-sabotage for the group, manager Sam Taylor wouldn’t authorise its release.

“I was told that Sam didn’t want our career to go too fast, so he didn’t want that song to be a single,” says Dug Pinnick. “He believed that we were going to be the next U2, the next Beatles, and he was going to control our ascent so that we wouldn’t peak too soon. I think he honestly thought he was doing the right thing, but he controlled us so much that I times I felt totally trapped. We all did. If we could have been more hands on, a lot of things would have been different.”

At the end of 1988, writers at Kerrang! voted Out Of The Silent Planet the magazine’s Album Of The Year, above Queensryche’s Operation Mindcrime, Metallica’s …And Justice For All and Slayer’s South Of Heaven. Even this acclaim, though, couldn’t help push the band’s US sales much north of 30,000 copies.

“We could not get it to cross over,” admitted Megaforce Vice-President Eddie Trunk, now the voice of hard on American radio. “We could not get it to sell. That was really, really frustrating for everybody.”

“I think the record company were under no illusions about the fact that we were going to be a difficult sell,” says Ty Tabor. “They were like, ‘Alright guys, thank you for giving us a great album, now we’re going to roll up our sleeves and keep fighting.’”

King’s X did keep fighting. Their second album, 1989’s Gretchen Goes To Nebraska, was another masterpiece, yielding a minor hit single in the gospel-tinged Over My Head, but it stalled at Number 123 on the Billboard 200. Faith Hope Love, their third album, made it into the top 100, peaking at number 85 in February 1991, after which the band hit the road with AC/DC.

When grunge – all down-tuned guitars and dark, angry, questioning lyrics – broke into the mainstream that same year, it briefly appeared that King’s X would be elevated in the slipstream of acts such as Pearl Jam and Alice in Chains, who were effusive in their praise for the trio, Pearl Jam’s Jeff Ament going so far as to claim on MTV that “King’s X invented grunge.” The endorsement changed nothing: in the midst of ’alternative’ rock’s most successful period, King’s X’s self-titled fourth album failed to rise higher than Number 138 on the Billboard chart. An ugly, bitter split with Sam Taylor soon followed.

“We were dumb musicians who didn’t know what the business was about, we just wanted to be rock stars like everybody else, and we got taken advantage of, just like everybody else,” says dUg Pinnick, his voice betraying resignation as much as bitterness. “We didn’t know what was going on, and Sam didn’t want us to know what was going on. When we did question it, it turned into a war. But we stayed with him, we believed in him, so that was on us. It’s like when a battered wife stays with her husband for 20 years despite everyone telling her to leave.”

By the time Atlantic Records dropped King’s X in 1996 following the release of that year’s Ear Candy album, the band had largely resigned themselves to the idea that they were not destined to be a superstar act. To their credit, across the decades that followed, they never dropped their standards – releasing six further superior studio albums - and never bemoaned their cult status.

“We might not be huge rock stars," says Pinnick, “but people recognise that we’re the real deal.”

Ty Tabor has the last word on the debut album that could, and perhaps should, have made these unassuming musicians superstars.

“It’d be too weird for me to look at Out Of The Silent Planet as an album to file alongside classics by The Beatles or Hendrix or any of our heroes,” he says, “but I just know that it was a very special moment for us. That people are still talking about it and discovering it over 30 years on is enough for me.”