This article was originally published in 2017, on the 10th anniversary of Sophie Lancaster’s murder.

Sylvia Lancaster hasn’t had a holiday for 10 years. When she says this, it’s not with annoyance or exasperation but a kind of surprise. “It’s only when we’re chatting, you think, ‘Has it been that long?’”

There’s a reason for her lack of downtime. For the last decade, Sylvia has dedicated her waking hours to The Sophie Lancaster Foundation, the charity named after her late daughter.

Sophie Lancaster, 20, and her boyfriend Robert Maltby, then 21, were attacked by a gang of youths on August 11, 2007. They had been hanging out at a park in Bacup, Lancashire. Sophie died 13 days later, while Robert was left with severe brain injuries. Five people, aged between 15 and 17, were arrested and jailed, two of them, Brendan Harris and Ryan Herbert, for life.

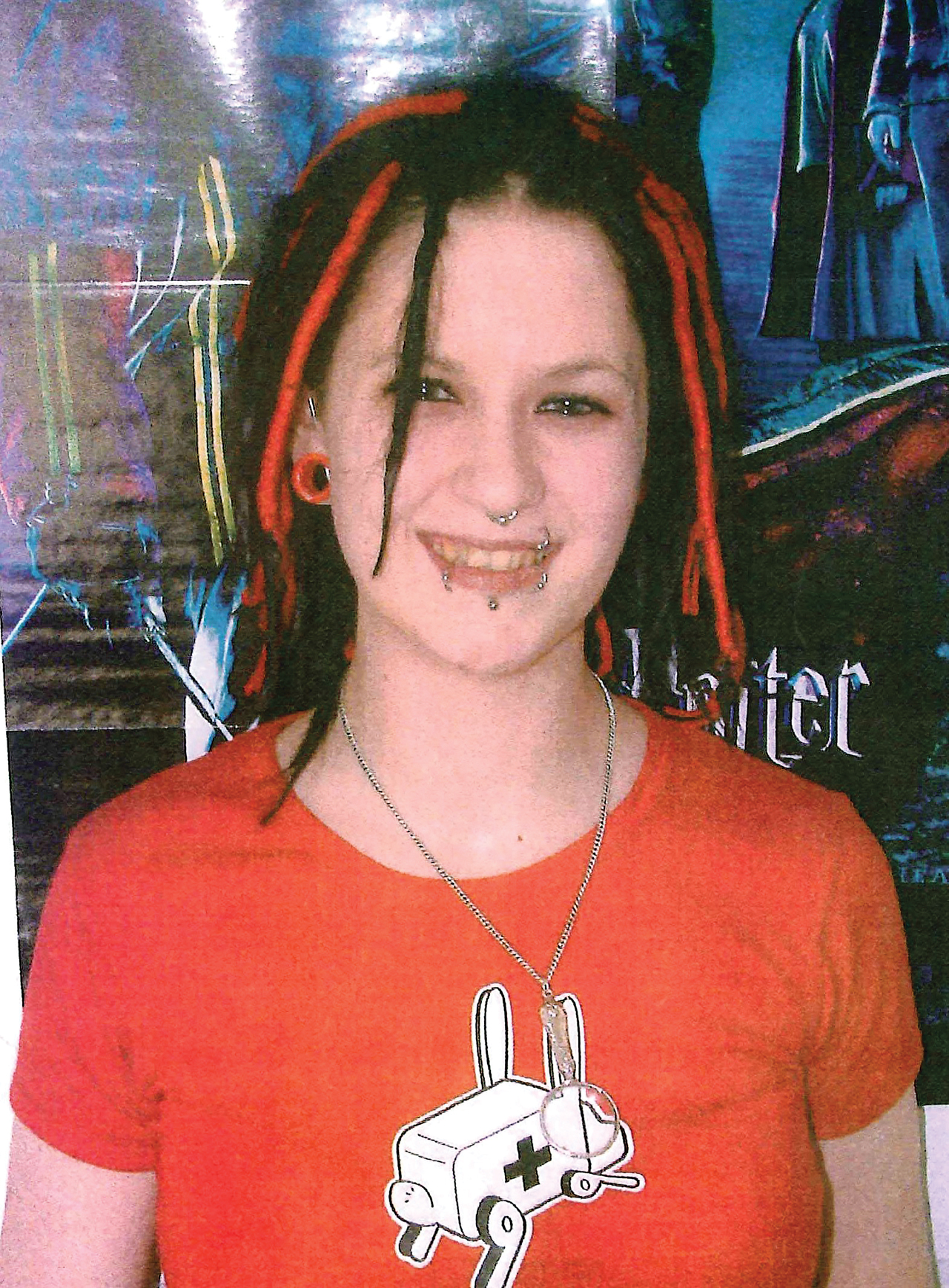

The attack happened because Sophie and Rob looked ‘different’: they had piercings, coloured hair. They were ‘goths’ in the eyes of the police and press, and ‘moshers’ in the eyes of their assailants. Her death was picked up by the media as an example of ‘Broken Britain’ – political shorthand for a society that was increasingly violent and heartless. But there was another, more human side to what happened.

Sophie’s death was a tragic waste of life, but it hasn’t been entirely in vain. Sylvia’s ceaseless work since has helped effect a change in the way attacks on fans of alternative music and the attendant lifestyles – whether that’s metal, goth, rock or anything similar – are viewed.

“You make your choice,” says Sylvia of the foundation she set up in her daughter’s name. “You can do nothing, or you can do something. And doing nothing was never my way anyway.”

Even before the attack on her daughter, Sylvia Lancaster had thought of setting up a charity that would offer support and help to people who found themselves being attacked verbally or physically because of the way they looked and dressed, or the music they listened to.

“You’d be out on the street with Sophie and Rob and you’d hear people making comments: ‘Look at the state of them, who do they think they are? What do they look like?’” says Sylvia, who worked as a youth advisor in schools before setting up the foundation with co-founder Kate Conboy, now production and development manager. “And you’d think, ‘Hold on a minute – you’ve got no right to be like that.’ That was the catalyst, really.”

The attack on Sophie and Rob changed everything. “I just remember at one stage walking through the hospital and going to the police, ‘I’ve had enough now, nobody else should have to go through this, I’m going to do something about it.’”

In the weeks and months after the attack, Sylvia threw herself into getting the Foundation off the ground. Starting a charity is a hugely complicated endeavour at the best of times: it involves solicitors and mission statements and aims and objectives. Doing it in the wake of such a huge tragedy – not to mention the attendant court case – took a single-minded dedication and unwavering focus. Fortunately, Sylvia had both in spades.

“Did I ever think it was too much?” she says. “No, it never even entered my head.”

Initially, they were awarded money from a scheme that seized cash from convicted drug dealers to help kickstart the charity (among other things, it allowed Sylvia and Kate to buy second-hand computers). Dark Angel, a 2009 animation based on Sophie’s murder and shown on MTV, helped raise the foundation’s profile. “It started very slowly and snowballed,” says Sylvia.

The same year, Bloodstock festival named one of its stages after Sophie, and the cause gained further exposure outside of the UK in 2012 with the release of the album We Are The Others by Dutch band Delain. The title track was a rallying cry that referenced Sophie in its first line.

“Our audience could really relate to it,” says Delain singer Charlotte Wessels. “I don’t know anyone who hasn’t been called names, or worse, for looking different or having a different way of life. When somebody tells you they feel less alone because of it, that’s really humbling.”

Today, The Sophie Lancaster Foundation’s aims are clearly stated on the home page of its website: “The charity… will focus on creating respect for and understanding of subcultures in our communities. It will also work in conjunction with politicians and police forces to ensure individuals who are part of subcultures are protected by the law.”

A lot of the Foundation’s work takes place in primary and secondary schools, though they are also involved in other youth groups and in prisons. Their work in schools involves talks and exercises on diversity and intolerance.

One exercise for secondary school children involves passing around sets of cards featuring images of different people, all with different looks, then asking the pupils to pick out five people that they would like to spend time with and two they don’t want to spend any time with. One of the cards that is frequently pulled out in the latter category is a goth/metaller called Phil with long hair, make-up and tattoos. “They say he’s queer, he’s a freak, he’s a murderer, he’s a paedophile,” she says, barely masking her disbelief. Another card that is pulled out features a picture of Sophie.

“I look at that picture of our Sophie, and she looks lovely,” says Sylvia. “I think it’s a fear of difference. Anything that’s different is scary.”

If the effect of what The Sophie Lancaster Foundation does in schools and prisons is positive but intangible, their work with police forces around the country is easier to measure. Thanks to the efforts of the Foundation, in 2013 the Greater Manchester Police became the first force to classify attacks on metal and goth fans as alternative subculture hate crimes. Today, 15 of the UK’s 45 police forces have expanded their hate crime classifications to include similar attacks – still only a fraction, but a growing one, as more plan to incorporate the change over the next few years.

“I first met Sylvia a few years ago when she was talking at a hate crime conference,” says Darren Goddard, Hate Crime Officer for Leicestershire Police, which introduced the new classification in 2015. “Sophie and Rob’s case, for me, broke the stereotypical notion of what a hate crime is. Because of the work we did with The Sophie Lancaster Foundation, when we moved to a new crime recording system, the next logical step was to say, ‘We’re now in a position where we can create an additional category for alternative subculture incidents and crimes.’”

While the new categorization doesn’t necessarily guarantee increased sentences for anyone found guilty of hate, it does mean that courts may consider the targeted nature of the crime when calculating the seriousness of the offence. “It means that people know they can now report attacks such as this and will be taken seriously,” says Darren. “They know that there is support for them and their friends and their community. That makes them feel safer and it can’t be a bad thing.”

National figures on alternative subculture hate crimes were unavailable at the time Metal Hammer went to press, but Greater Manchester Police statistics show that there have been a total of 109 attacks of this kind since 2013 in that region alone. Leicestershire police don’t have specific numbers, but Darren puts it at “single figures” per year.

By the estimates of both Sylvia Lancaster and the Leicestershire Police, only a fraction of attacks on metal, goth and alternative people are reported to the authorities. According to Sylvia, Sophie and Rob themselves had been attacked three times previously.

“What they think is, ‘Oh, it’s just a part of who we are, we just have to put up with that,’” she says. “Actually, no you don’t – you don’t have to put up with it.”

Sylvia speaks directly to people who have been on the receiving end of hassle and worse because of the way they look. At this year’s Download festival, she talked to a couple in their 40s who had just been attacked in the street. “They weren’t kids, they were adults,” says Sylvia. “We hear this kind of thing all the time.”

For legal reasons, The Sophie Lancaster Foundation can’t give advice to anyone who has been or is currently the victim of a hate attack, but Darren stresses the importance of reporting such incidents to the police – whether that’s by the victim or someone who witnesses it happening.

“We may not always prosecute, but if we don’t know about it then we can’t try and make things better,” he says. “And for passers-by, there’s so much people can do without putting themselves as risk, whether that’s helping to pick up their stuff if it’s been thrown on the floor or offering to give the police their name for a statement. That’s a huge help to the victim.”

“I hope that people feel confident enough to speak out about what’s happening to them,” says Delain’s Charlotte Wessels. ‘We need to support each other and help each other and make sure people don’t battle alone.”

In June 2017, Robert Maltby gave a rare and moving interview to the Guardian newspaper. In it, he talked about his relationship with Sophie as well as the night of the attack and its aftermath for him. He also lamented the fact the media were only viewing the attack from one perspective. “Why can’t we ask what it is about them that made them want to murder someone?” he said. “Not what it is about someone that made them be murdered.”

It’s a sentiment that Sylvia Lancaster agrees with. “Absolutely. We do need to look at the roots of things. Governments, because they’ve only got a five-year term, they don’t look at a long-term strategy, which is really what they need, even though they’re pretty hot on hate crime, in fairness.”

“As a society, we need to work together as communities, as groups of people, to say: ‘Not in my town, not in my village, not in my city’,” says Darren. “If we do that, we won’t need to hold people to account – because the ultimate dream is that people won’t be going out there perpetrating it.”

August 2017 marks the 10th anniversary of the events that cut Sophie Lancaster’s life tragically short. Sylvia says that she always marks the event privately (“I just stop at home”), and this year will be no different. There is talk of a tribute gig in Manchester in November, though it’s still in the planning stages. BBC Three have aired a real-life drama called Murdered For Being Different.

Over the last decade, she has slowly seen attitudes changing – in schools, in prisons, even in the police force. “People have reported this sort of thing in the past and they’ve been treated like scumbags,” she says. “The general public don’t see how much the police are moving forward and desperately trying to change that. You’re getting young people coming into the police force, and they already know about diversity and whatever.”

There’s still a lot of work to be done. Thirty police forces have yet to add ‘alternative subculture’ to their list of hate crime categories, though Sylvia is confident this will happen. And the Foundation’s work in schools, youth groups and prisons is an ongoing project.

“We’ve only just started,” says Sylvia. “We’re just scratching the surface. What we find when working in schools is that young people know they’ve not got to be racist. In another 10 years, we’ll be on a level with that.”

She signs off her emails with the words “Love and light”, and the phrase appears on the Sophie Lancaster Foundation website. Sylvia says there’s no religious dimension to the words; for her, they’re simply a way of looking at the world. “It’s just the way it is,” she says. “I think people should have a bit more love and light in their lives, shouldn’t they?”

For more information, visit the Sophie Lancaster Foundation