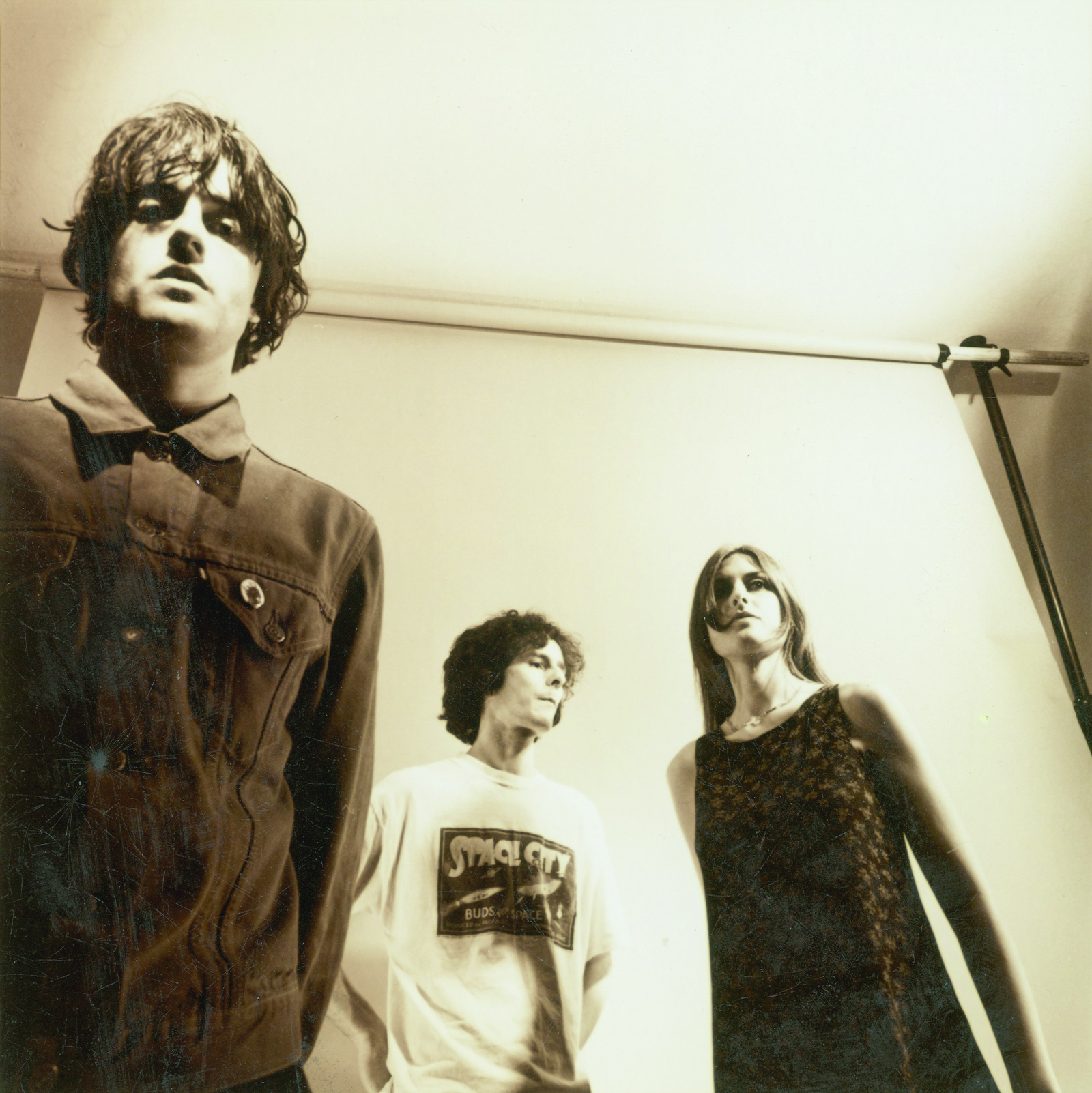

After nonchalantly transcending categorisation for three decades, Spiritualized re-emerge into this curious new era as long-established legends of multifarious, exploratory psych. Formed by singer and guitarist Jason Pierce upon the disintegration of his previous band, UK psych icons Spacemen 3, they defied every prevailing trend by becoming one of the most admired and acclaimed bands of the 90s, releasing a dazzling flurry of studio albums along the way. When it all began, however, Pierce was far from buzzing with expectation.

“I’d been in Spacemen since I was 17 but for whatever reason it just would have been more painful to carry on. I’m not and have never been interested in making money. It’s never been about that for me. So to carry on for that reason was not the right thing to do. But I didn’t have any confidence. I still don’t have self-confidence, so it was very difficult to find myself on my own. But I didn’t have to run any ideas past anybody, I didn’t have to say, ‘So what do you think of this? What can you contribute to this?’ So there was a massive freedom. Fear and freedom in equal measures!”

As showcased on glorious debut Lazer Guided Melodies, Spiritualized were a much less claustrophobic and more uplifting sonic experience than anything Pierce had created with his former band. To the outside ear, Spacemen 3 made music for tripping one’s balls off in front of a giant, flickering TV. Spiritualized, on the other hand, made music for tripping one’s balls off outside in the sunshine.

“Yeah, I like that, that’s quite nice!” Pierce chuckles. “There wasn’t a plan to make it less claustrophobic, it just kind of happened, like these things do in music. I’d already made four or five albums with Spacemen, so it wasn’t like any of these ideas had much history or dated back. I guess it was also about finding a new musical vocabulary. In Spacemen we were into similar things, whether it was 13th Floor Elevators, Marc Bolan and T. Rex, The Troggs, the Electric Prunes. It was mainly these American bands that desperately wanted to sound like the Rolling Stones but were chewing acid at the same time and it all came out wrong. It wasn’t progressive, it was still rock’n’roll based.”

Released in the spring of 1992, Lazer Guided Melodies was one of the few genuinely psychedelic statements being made at that time. Although audibly linked to Spacemen 3 via Pierce’s simple but distinctive songwriting, it brimmed with gently expressed but eccentric musical ideas, with everything from minimalist drone to opulent soul music hazily identifiable. As organic and unplanned as it evidently was, Pierce’s musical vision was coming together beautifully.

“I’d found a lot of other stuff that didn’t seem to fit with that 12-bar psych thing: a lot of John Adams, Steve Reich and particularly Michael Nyman, who I really fell in love with around that time. I was still into stuff that droned and that sat in that same opiate space, but it wasn’t restricted to rock’n’roll anymore. There were threads between all of it, and it was all music. You could find the lines that joined gospel with rock’n’roll and soul. It all started to open out and it felt like I could make connections between things that made real sense.”

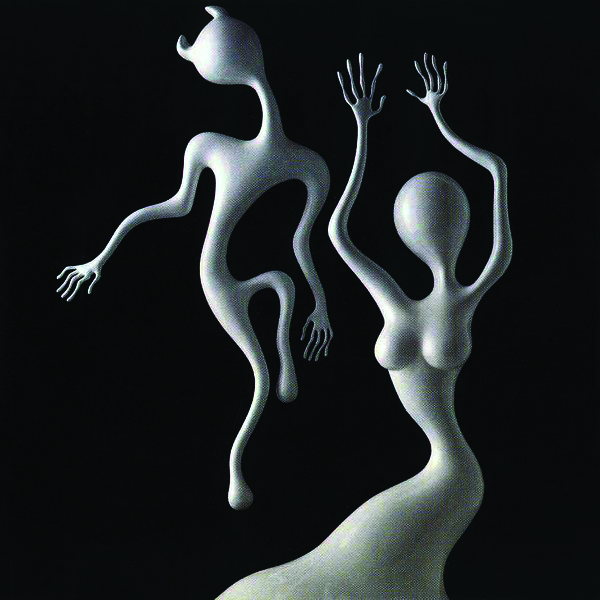

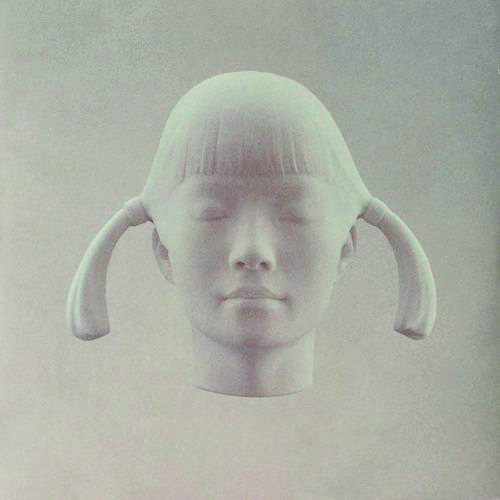

Those connections truly blossomed on Spiritualized’s second album, Pure Phase. Released under the augmented heading of Spiritualized Electric Mainline, it was so utterly at odds with everything else that was happening in mainstream music 1995, not least Britpop and grunge, that its subsequent success now seems like an audacious stroke of good fortune. But what an album: Pure Phase took the blueprint laid down on Lazer Guided Melodies and flung it down a swirling vortex of lysergic ingenuity. A genuine headfuck, in the best possible way, it was released in a deeply stylish, glow-in-the-dark, ‘encapsulated’ CD case and sounded every bit as alien and irresistible as it looked.

“We’d done two mixes for Pure Phase and I was unhappy with both,” Pierce recalls. “But then I was working with [mixer and multi-instrumentalist] John Coxon for the first time in London and he suggested that we run both mixes, one in one speaker and one in the other, and cut them up until they fit together. If they went too out of phase, you’d get a proper phase like a Hawkwind thing, which wasn’t what we were after. But once we’d done that, and played just 10 seconds of the two together, we just had to do it. So the Electric Mainline thing was just trying to encapsulate this sound that we’d stumbled upon.”

Best experienced on headphones, Pure Phase remains the most sonically perverse of Spiritualized’s records and re-emerges on remastered vinyl with its mostly white artwork newly reborn in bright green. One thing that Pierce has no interest in doing is remixing any of these albums, and with Pure Phase in particular, you can hardly blame him.

“I don’t believe in changing things for the sake of it,” he notes. “But it was an accidental find back then, to have the two mixes left and right. It means that you couldn’t reproduce it. If you had any kind of plan you couldn’t place the bass drum where it sits in that mix because it’s the product of two bass drums, one left and one right, and slightly out of phase with each other. So it doesn’t sit in the centre and it doesn’t sit on either side either! It was all predigital, so we couldn’t just lock the mixes together and let the whole thing run. We had to cut the tape up into six or eight bar sections, and relock them with every bass drum, every few bars, and then start again. It took forever, it took months, but it was beautiful, and the result was extraordinary.”

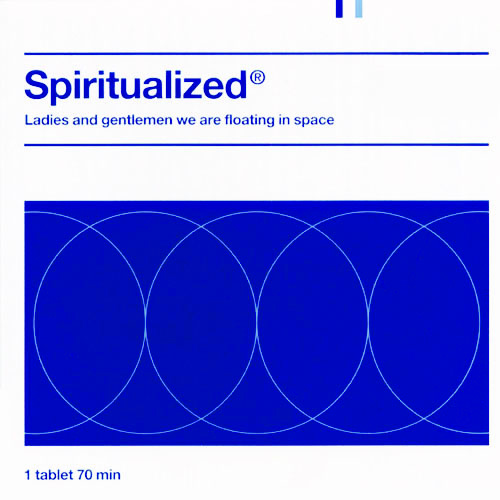

Two years on from Pure Phase, Spiritualized released an album that, whether he likes it or not, will almost certainly be the record for which Pierce is most widely remembered. Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space was recorded between 1995 and 1997 and was the most gleefully ambitious album the band had yet attempted. A huge critical and commercial hit, it expanded their sonic remit far beyond their previous efforts, taking in everything from sparkling gospel – courtesy of the London Community Gospel Choir – and swampy, New Orleans jazz through to space rock, disorientating, abstract noise and, of course, more drones. For Pierce, it was simply the next Spiritualized record, made during a time when he enjoyed major label support and an avalanche of opportunities.

“Maybe Ladies and Gentlemen… was more ambitious, but maybe I was just being supported at that stage,” he muses. “If I wanted to work with a gospel choir? The attitude was, ‘Let’s do it!’ You want to go to New York and work with Dr John? Let’s do it. So that’s all slightly outside of my control, and there’s an element of luck to that, as well as somebody believing in what I was doing. It’s still the same songwriting. But a lot of things happened. I met Mark Farrow, the sleeve designer. The concept is beautiful. It had a lot going for it, to lift it out of the mundane. A lot of things fell into place in the right way.”

Best known for alternative radio bangers like Come Together and Electricity, Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space is also notable for its mind-blowing finale, Cop Shoot Cop. Seventeen minutes in length and simultaneously beautiful and berserk, it was an audacious statement from a band who were, albeit reluctantly, widely seen as being part of the indie rock world. Fervently progressive in intent and execution, Cop Shoot Cop even boasts a magical cameo from the late, great Dr John.

“Oh, he was amazing,” Pierce sighs, still in awe. “I’ve seen photographs of that session and I couldn’t stop smiling! I was overjoyed to be working with him, which in an odd way marred it slightly. The line is, ‘Never meet your heroes because they’ll disappoint you,’ but it should be ‘Don’t meet your heroes because you’ll disappoint yourself!’ I just get tongue-tied. There’s so much I could say and talk about. But it was still magic, both that he said yes, but also that he was sold on the song. He was really intrigued by the whole thing. It was meant to sound like the listener was travelling from New York to LA, which was something we did often when we were touring. It was about trying to make sense of America.”

Despite a comprehensive line-up change, Spiritualized sustained their momentum and entered a new millennium in fine form with 2001’s Let It Come Down. Where the band’s previous records had all boasted significant electronic and drone elements, their fourth embraced a volubly organic and acoustic approach, with Pierce’s songs being largely built around orchestral instrumentation. As with Ladies And Gentlemen…, the album took the best part of two years to make, as Pierce one again revelled in the minutiae of recording.

“I suppose Let It Come Down was about writing all the parts, the flutes, the French horns, and yeah, it took a long time to do,” he says. “But it doesn’t bother me. I just feel like you’ve got one chance to do these things and you have to make them as good as they can be, and you have to get the most enjoyment out of them. I don’t write that many songs, you know? Most people edit down their material to nine or 10 songs, to make an album. I’ve only got nine or 10, so I have to pull them all up to being of high enough quality to be on the record. I get enjoyment out of that, out of obsessing over every tiny detail of it. I’ve never made a deadline in my life. They’re finished when they’re finished.”

Speaking of which, Pierce tells Prog that he’s recently finished work on the next Spiritualized album. The band were only just beginning to promote their previous record, And Nothing Hurt, when the world was suddenly shut down, and Pierce is eager to get back on the road and pick up where he left off, albeit with another album of new material to share with the faithful. Meanwhile, he’s clearly very pleased to have overseen the remastering of his band’s first four records. As with everything he does, the process has been meticulous and a labour of love, with the end goal of transporting listeners old and new with some of the deepest and coolest psychedelic music of the last 30 years.

“I just wanted people to know that these records are being cared for. I did this to reclaim them, in a way. When you leave a major label, your records are forgotten about, and they’re thrown out to basically anybody who wants to press a couple of thousand copies. The money doesn’t go to anybody, except to pay back the debt to the label. That’s fair enough, but I wanted to reclaim them and not have them released by people who didn’t care about them. It just felt wrong to let that happen. They’re too beautiful.”

This article originally appeared in issue 121 of Prog Magazine.