In 2019, Hawkwind interpretive dancer Stacia Black made a guest appearance with the band for the first time since her departure in 1975 – the same year Lemmy had been fired by the space rock icons. She took the opportunity to give Prog a tour of her lifelong work as an artist.

My story has written itself,” Stacia Blake tells Prog. “It’s been written by people who’ve never met me or spoken to me. Then when I say something people say, ‘Oh, that can’t be true, because I’ve read it somewhere else.’ And I go, ‘Well, I was there!’”

There are many stories about Stacia, Hawkwind’s dancer and performance artist during their golden era of the early 1970s. According to some reports, she joined the band at the behest of lyricist Robert Calvert. Other accounts state that she first saw Hawkwind at the Isle Of Wight Festival, that she made her live debut with them at Glastonbury in ’71, that she was romantically involved with Nik Turner and had once been booted out of ballet school for being too tall. Her Wikipedia entry still lists Ireland as her place of birth. None of these things are true.

The second-hand mythology surrounding Stacia is partly down to her wariness of the music press. An intensely private person, she kept a low profile during her downtime with Hawkwind, preferring, for the most part, to shun interviews. After parting company with the band in 1975, she relocated to Germany with her husband Roy Dyke (of Ashton, Gardner & Dyke fame) and more or less disappeared from public view. Stacia eventually settled in Ireland, studied at various art colleges in the 90s and has since exhibited her work in Asia and across Europe.

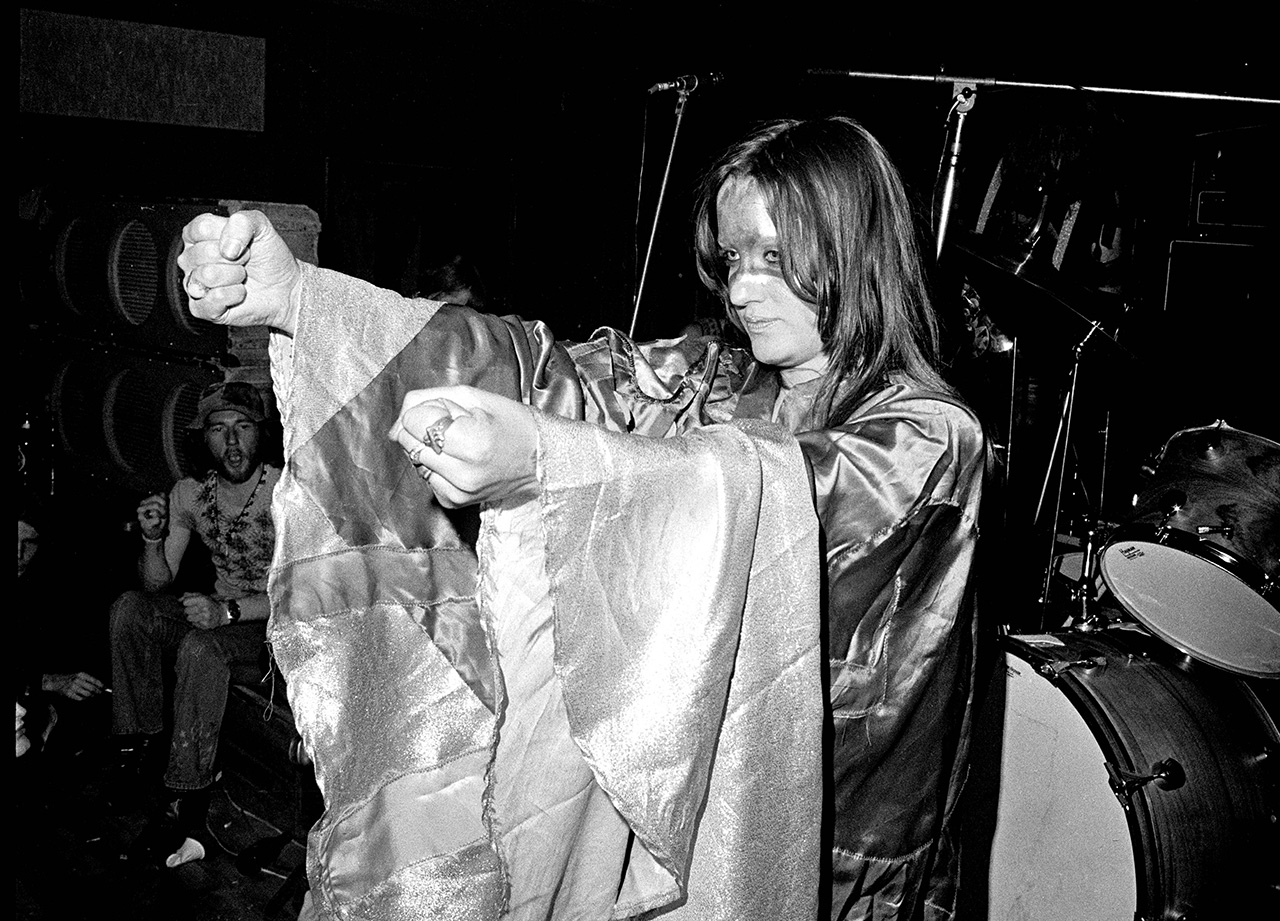

For diehard Hawkwind fans – whom she calls “Hawkwind family” – she remains an iconic figure, the statuesque presence whose interpretive moves (either semi-naked or nude) formed an essential part of the band’s audio-visual experience. “We were all a vital part of the live show,” she tells Prog in 2019, pushing back her mane of grey hair. “It was all about free expression.”

It was, too, a challenging role for a woman in the male-dominated music business of the 70s, with all its attendant chauvinism and fixed perceptions. “It wasn’t an easy time to be a woman in the industry,” Stacia reflects. “Some people, and I won’t mention any names, would’ve looked down on me because they didn’t feel I was part of the music thing. They thought I was just a spare part, if you like.”

Now aged 66, Stacia remains cautious when it comes to doing press. Our interview has been a couple of months in the planning and, apart from lining up a chat with BBC radio, is the only one she’s agreed to for the time being. The whole experience, she says, makes her feel self-conscious. Prog meets her at Dublin airport, where she’s just flown in from watching Joan Baez in Glasgow the previous night. As tends to be the case wherever she goes, Stacia met up with a bunch of Hawkwind fans during her stay in Scotland, producing a Loch Ness Monster plush toy that one had her given her. We find a table at an airport eaterie, sit down with a couple of veggie wraps and begin to unpick fact from fiction...

You live in Ireland now, but where were you born?

I was born in Devon, in Exeter, and lived there until I was 17, when I started touring. My father was an English Protestant and my mum was a very warm, Irish Catholic woman. She was very active with Oxfam, collecting funds for years, and collecting funds for Macondo, a centre started by my auntie in Uganda to feed children with AIDS. She also supported the campaign to free Nelson Mandela and visited prisoners in Exeter for years. She supported charities; too many to mention.

What were your earliest ambitions?

The first thing I wanted was £1,000 in my bank account. And to make a record and be in a film. That was what I wanted at eight or nine years of age. The money was the most important thing, because it represented freedom.

Were you always a free spirit?

Definitely. I didn’t really plan anything, I just had those ideals.I wrote to Omar Sharif after I’d seen Doctor Zhivago [1965] and told him everything that I wanted todowithmylife–toactand everything else. I didn’t get a reply for a year, then all of a sudden I got a letter and a photo from Egypt. He just said yes, you can do all those things, but do your schooling first. It was so kindly written.

So your main goal was to be an actress?

I wanted to be a performer. I was always dancing around the place and putting on little plays with my mates. We’d sort of hang up sheets and stuff to make a little theatre, then put on plays for the neighbourhood.

Can you clear up the story about how you met Hawkwind in 1970?

I met Nik at the Isle Of Wight Festival, we got chatting and he told me all about the band and said that they were playing there. But I never went to see them at the inflatable [Canvas City, an inflatable tent], so that’s a myth. I then zoned out with my friends and didn’t see him again until I turned up at a gig in Exeter. I went along to see Nik, basically, more so than to see the band. I found him an interesting person.

It’s also not true that I fancied Nik. I’m the kind of person who will talk to anybody. I find people interesting, I don’t care if they’re men or women. But at that time, people were inclined to put a slant on everything. If a woman made conversation with a man, then people automatically presumed there was something there.

I believe that the first time you appeared on stage with Hawkwind was in Redruth...

That is true – the Flamingo Ballroom [April 15, 1971]. I hitched down to the Flamingo to see them play and asked them if I could dance. Being typical males, they said, “Yes, if you take all your clothes off and paint your body.” I don’t think they really thought that I’d do it, but I said, “Yeah, OK.” I suppose it was some kind of a dare from the guys, but for me it wasn’t a problem at all. That’s the way I was born.

What it was like to be in the centre of that intense multi-media live show with Hawkwind on the Space Ritual tour?

It’s so difficult to put something like that into words, because you’re so in the moment. It was awesome, obviously. We were really lucky to have [fellow dancers] Miss Renee and Tony Carrera with us on Space Ritual too. They were two great talents. We were all as important as each other, in my mind. We were all cogs in the machine.

Did you ever have any stage direction beforehand?

What I did was totally up to me. A lot of it was interpretive dance, which was just going with the music. There were no set sequences. I had my robot routine, which always cropped up. It was basically a robot who’s given a pill and comes to life, then at the end of the sequence the pill starts to wear off and he begins to turn back into a robot and becomes frantic, because he doesn’t want to return.

Did you study dance at all?

No. I was totally self-taught, an autodidact.

What was it like hanging out with an all-male band like Hawkwind?

It was good, but it could also be very difficult. It could be very lonely at times, being the only woman. A lot of the times the guys would go off to a party or whatever and I’d be at the hotel on my own. I used to just go out and meet people, everyday people. I made friends with teachers and florists and people who worked in the police department when we were in the States.

Which members of Hawkwind were you particularly close to?

Lemmy and I seemed to connect from the first time we met, which is probably due to the fact that we were born two days apart. He was born on December 24 and I’m on the 26th. So we connected from the beginning. We were close.

We used to get on each other’s nerves sometimes, like everybody does, and the same goes for the rest of the band. Anybody who says it was all plain sailing is lying. You can’t live that closely with so many people without having times when you don’t particularly want to see each other. Though it was never the case with Lemmy that I never wanted to see him. For Lemmy and I, Hawkwind wasn’t a job, it was like family. That’s why he was so devastated when he got fired.

What were his best qualities?

He was one of the most caring people I’ve ever met. If he wasn’t going to do something good for somebody, he definitely wasn’t going to do something bad. He was a caring, loving gentleman.

I’m guessing his death in 2015 must have hit you pretty hard?

Yeah, it did. I was all but ready to go myself when I heard that. I was devastated. My personal messages went crazy for weeks, with guys in bits. We were all heartbroken. For weeks I chatted with the Hawkwind family. The grief was overwhelming.

What do you recall of Hawkwind at Glastonbury in 1971?

All I remember was riding around on a Harley-Davidson wearing only a pair of white underpants and a little Pink Fairies badge on it. That’s my main memory. I have no idea who was driving the Harley!

Did you notice Hawkwind’s audience change at all after Silver Machine had been a hit?

I suppose we started attracting a lot of younger people after Silver Machine, but essentially it was the same, before and after. The kind of music that Hawkwind played appealed to a certain kind of person. So they were basically all freaks and misfits, like the rest of us.

Even today, people talk about Hawkwind fans, but I call them Hawkwind family, because no matter where you go, you meet with them and it’s like you’ve known them all your life. It’s only twice that I’ve had any problems with fans. The first one was when somebody tried to strangle me on stage in St. Louis. And there was a recent meeting with some people who recognised me in the street, which I had problems with. I won’t go into details about that. But I’m a very trusting person, so that experience set me back a little bit.

What happened with the guy who attacked you in St. Louis?

I think the roadie spotted him first. When I ran off stage, somebody had grabbed him by then. I’ve thought about it so much over the years and I wonder did he really mean to hurt me. Or was he just out of his head and over enthusiastic? Maybe he just wanted to give me a kiss or a hug. I like to think that was the case.

It’s an obvious question, but were there many drugs involved when you were performing?

[Laughing] No, of course not! Absolutely not [still laughing].

Did drugs enhance the experience for you?

It’s difficult to say, looking back. I suppose it did. It would’ve happened the same without them as well, definitely. But of course you’re right when you say that it enhanced everything.

You were involved with Arthur ‘Killer’ Kane of the New York Dolls at one point. How did you get together?

We met in the Rainbow Rooms at the Biba building [November 26, 1973], when the Dolls were playing there. Arthur was a very special person, like Lemmy. A real gentleman. I still love the man. We weren’t together very much, just when they were in London and whenever we played the States. On my 21st birthday [December 1973] I went to New York and spent it with him there. We went to Max’s Kansas City, amongst other places.

There’s also a story about you performing at a press launch for Alice Cooper at Chessington Zoo in 1972...

I just upstaged a stripper, that’s all [laughing]. I wasn’t being a stripper, I was trying to make a statement, but it was totally misconstrued.

What kind of statement?

I don’t know how to put it into words. We’re all women or men or whatever and our bodies are beautiful and sacred. And just to see a woman there, stripping, I had to get out there and do something for the other side, if you like, the alternative scene. I hate it when people say that I was a stripper or that I danced topless and stuff like that. I was never a stripper and I never danced topless. I wore costumes where my breasts where bare, but I never considered myself a topless dancer. There was never anything sleazy about my performances; they were interpretive dance. I think some men and women felt threatened by a woman appearing nude.

Hawkwind famously played a gig at Wandsworth Prison in February 1973...

Of all the bands that you would imagine playing in a prison, it’s amazing that they would choose a bunch of totally open, drug-using freaks to do a show. Not only that, but to allow a dancer in as well.

A lot of people probably think that it was sleazy, because I was dancing with them – and that the prisoners would’ve been sleazy too – but that wasn’t the case at all. Everyone treated me with total respect. There was one prisoner in particular who just wanted me to send him some books. People in prison have done whatever they’ve done, but they need some kind of caring, someone to reach out to them. And I think that’s what we were for them. It was a very positive experience.

Why did you leave Hawkwind?

I can’t answer that question. You’d have to ask the others.

But you left of your own accord?

[She gives a look that indicates no.] As I say, it’s maybe best to talk to the band about that. People always ask, “Why did you leave?” and I never say I left. I always say, “When I was no longer with them.” Did I miss it? No, I just got on with my life. You dust yourself off, get up and get on with it. Two weeks after not being with Hawkwind any more, I was working in a supermarket, at a cash desk in Swiss Cottage.

You married Roy Dyke around that time. How did you spend the rest of the 70s?

We got married the day after the Reading festival and a year later we had our beautiful daughter. Then we had some visitors from Germany, who wanted Roy to join a band in Hamburg. So we went over to live there. What did I do? Let me think. I scrubbed toilets, I worked in pubs as a cleaner, I worked in kitchens, in factories, in kindergartens – doing the same thing, cleaning and cooking, whatever I had to do to keep my family and Roy and myself going.

Then in 1983 I opened my own business, doing nail extensions. I also did some backing tracks on an album for a Dutch guy called Jan Ten Hoopen. And I did some extra work on one of the first videos for an Italian musician called Milva [singer and actress Maria Ilva Biolcati].

When did you start producing art?

I’ve always been artistic. In the 80s I would’ve been painting, as well as running the business. So I just painted for my own pleasure. I wanted to get out of Germany. I’d separated from Roy and remarried. Then my second husband and I sold up everything and moved over to Ireland.

And I went to art college. First of all I did a tenure at Senior art college [Limerick] to do my portfolio, then I chose to go to Crawford [in Cork]. It was a terrible experience. They gave me a really hard time, criticising me and telling me that I had no talent. I then went to Finland on an Erasmus exchange, which was amazing.

The most important thing for me, in terms of my artwork, is something that I started doing in 2006, called Peace Work. It’s in memory of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I started working with a circle, so everything I do consists of circles, each one representing a victim of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I’ve travelled to Japan three times to exhibit it there and also in Germany, Finland, Ireland and Northern Ireland. That’s what my main work is now.

The Hawkwind thing, Miss Stacia, is a separate project. We’ve brought out limited editions of T-shirts and posters with a design that Barney Bubbles created as a letterhead for me in the 70s. It’s a beautiful design.

What else do you have going on?

We thought we’d have a go at doing an album, collaborating with different musicians to see what we can come up with. I can’t really tell you any more about that at this stage, apart from the fact that one of the bands on there will be Visceral Noise Department [a heavy Glaswegian four-piece].

Is the album likely to consist of original songs?

At the moment it’s all open. I’m going to collaborate with Visceral Noise Department to write, then there are some other musicians who I haven’t met yet. So there will probably be new songs and covers.

Also there’s the Lemmy Foundation, a charity that we’re trying to form, which will help heroin addicts. When Lemmy died, I wanted to do something in his memory, so I decided I was going to start this charity. That’s what the album will be for, to raise funds for it. The love of his life died of a heroin overdose.

Will that interfere with your painting at all?

I’m not really painting at the moment. Right now I’m working on my autobiography. It’s all over the place – I hop from being 10 years old to being 17 to being 60. I’m severely dyslexic, so I don’t write in the usual narrative way. I remember this, I remember that. If it was chronological, it just wouldn’t be me!