Two albums and four years into their existence and with their music already labelled by some as ‘what The Beatles might have done if they hadn’t split up,’ in 1973 cheeky Bristol prog types Stackridge found themselves in a studio with their production hero George Martin. But were they about to lose their heads for The Man In The Bowler Hat?

Rising from the ashes of the Goon Show-inspired Griptyte Thynne and morphing from Stackridge Lemon to just Stackridge, by 1973 the knockabout Bristol pop-proggers had racked up some serious milestones in four years of existence.

Initially comprised of Andrew Cresswell-Davis (sometimes credited as Andy Davis) on guitar, keyboards and vocals; James Warren on guitar and vocals; James ‘Crun’ Walter on bass (Crun was also a Goons name); Michael ‘Mutter’ Slater on flute and vocals; Mike Evans on violin; and Billy ‘Sparkle’ Bent on drums, the band members had met in the clubs and bars of Bristol, such as Acker Bilk’s Old Granary and The Dug Out.

The players’ chemistry went from performing pop and blues covers to original songs infused with a Bonzo Dog Band playfulness and eclecticism, taking in classical music, tea dance and music hall, rock, pop, folk and anything else that took their fancy culturally, created with humour and heart. They soon positioned themselves as a slapstick alternative to the popular rock du jour.

“We drew from every imaginable source,” James Warren tells Prog. “It was a weird mixture of Beatles, Frank Zappa and The Incredible String Band, and a healthy doze of musical theatre and humour.

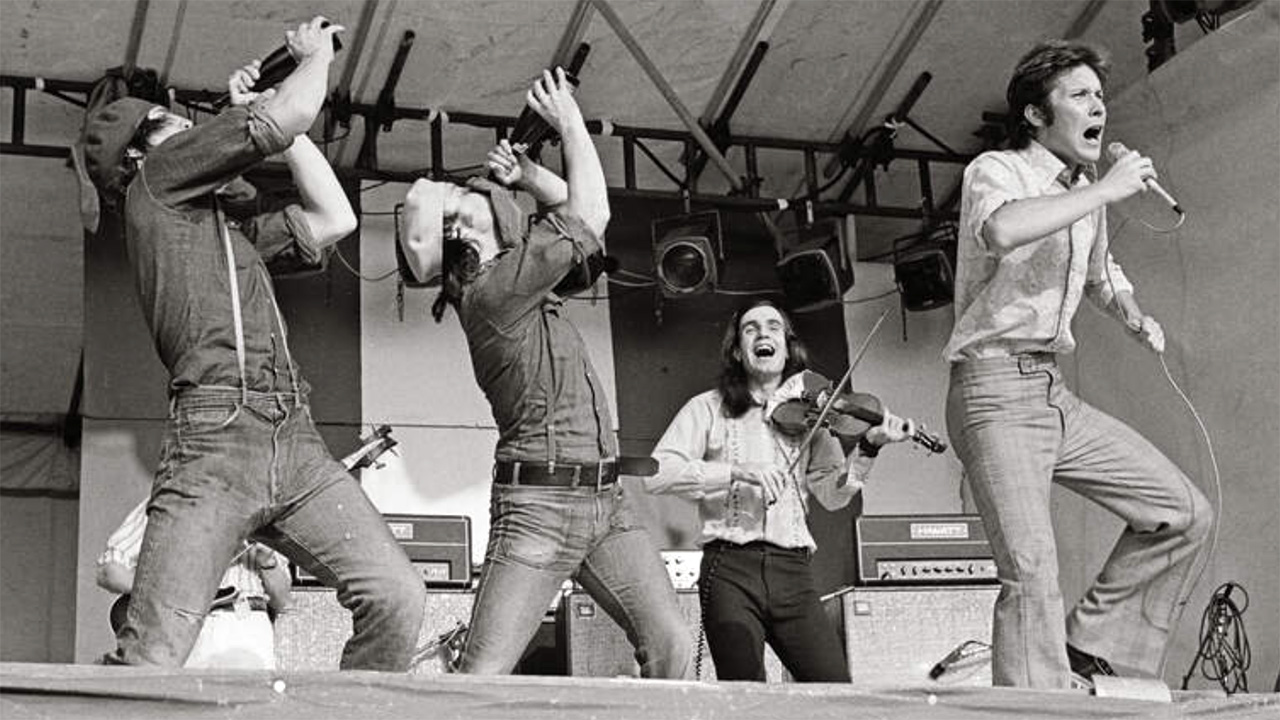

“We were determined to not be denim-clad like Free, Status Quo or Black Sabbath,” Mutter Slater says. “We wore waistcoats, grey flannels and braces. James wore slippers.”

Stackridge opened and closed the first Glastonbury Festival in 1970, recorded two well-received albums on MCA (1971’s Stackridge and 1972’s Friendliness), toured with Wishbone Ash and Renaissance, appeared on The Old Grey Whistle Test, and recorded a Radio 1 session for John Peel. After playing more than 300 shows, they’d garnered a battalion of enthusiastic and rather nutty fans, known for bringing props to gigs to join in with numbers that required participation, such as Marzo Plod with its rhubarb-thrashing, or dustbin lids for Four Poster Bed (Let There Be Lids).

Following the Cockney-Edwardiana dance-craze single Do The Stanley, a UK tour saw them supported by Camel, and their next big achievement was just over the hump. As avid Beatles and Goon Show fans, it was almost too much for the fluctuating five-, six- or seven-piece: the recording of album number three, The Man In The Bowler Hat, would be with The Goons’ label manager and fifth Beatle himself, George Martin.

Being the huge Beatles fans that we were, it just didn’t seem possible that we’d somehow join that sort of world

James Warren

Stackridge’s creative life was almost ‘easy’ by today’s standards: most band members and their roadie Pete Donovan shared a flat in Clifton, Bristol, living on a shoestring (and the dole). Later, as they got more popular, three nights a week they had digs in Bayswater, London, secured by their dedicated agent-turned-manager Mike Tobin. Each day was filled with writing, playing gigs and recording the means to their modest ends.

“I think back and wonder how the hell we ever managed to stay under the same roof for a year or two because we were incredibly different people, but we had a fun Monty Python-ish sort of time,” says Warren.

Promoting Friendliness, the band were frequently in the capital, or playing nearby towns. George Martin’s sons Greg and Alexis were often in the audience. “They loved us,” says Warren. “We’d see them at gigs and get chatting, and around the same time our manager Mike was offered a job with George Martin’s AIR Enterprises, a band agency and producers’ agency.”

Tobin was an effective businessman with a good ear and had been successful at Bristol’s Plastic Dog agency and London’s John Sherry Enterprises. He didn’t directly deal with Martin, but he was in the perfect location to approach him with an idea.

“Because George was coming into the office regularly, Mike got friendly with him,” Warren says. “One day he had the temerity to say, ‘Greg and Alexis have been coming to my band’s gigs and they absolutely love them. Would you be interested in listening to some demos they’ve done for their next album?’

“George agreed, and he obviously much liked what he heard, because – to our utter astonishment and amazement – he agreed to record and produce an album. It was a total dream. Being the huge Beatles fans that we were, it just didn’t seem possible that we’d somehow join that sort of world.”

In preparation for the sessions, Stackridge were invited to Martin’s place in Paddington, and most of the band – Warren, Slater, Walter and Evans, but not Cresswell-Davis, who had married – were relocated to Stansfield Road, Stockwell (the street where David Bowie was born). “And two girls from the Bayswater flat moved in, too,” laughs Warren.

“We spent about a week or two going to George’s. We had to plan all the tracks that we were interested in recording. George would cogitate a bit, going, ‘We could do this or that and that would work quite nicely,’ and so on. He was earmarking songs that he could do some orchestral arrangements for, and then a big production number on.”

Because of the music we thought the lyric should have a dark underbelly. But we always tried to not be too literal

James Warren

“We were a bit starstruck and didn’t know how meeting George would go,” says Slater, “but he’s an avuncular man and one of his gifts was putting you at ease.”

With a title inspired by Magritte’s surrealist painting – a man in a bowler hat isn’t on the cover, but there’s a young woman in some sort of titfer, wearing an apron – the album tracks were as wide-ranging in style as in the past two records. Each member was encouraged to come up with musical ideas, and much lyric writing was done by a partnership of Warren, Jim Walter and Mutter Slater, which would occur “late at night, after coming back from gigs, over copious cups of tea and bowls of muesli,” says Warren – or “the burning of the midnight cornflakes,” as Slater puts it.

These compositions would be credited to the charmingly named ‘Smegmakovitch,’ while whole group co-writes went under ‘Wabadaw Sleeve,’ an anagram of letters from the members’ names.

The band had 10 days for recording and two for mixing at AIR Studios, which was then right in the centre of the West End, in Oxford Circus. “George was away quite a lot as he was working with Mahavishnu Orchestra or Jeff Beck, and he’d be flying to New York for meetings,” says Warren. “We had Geoff Emerick and Bill Price engineering the album, and these extra musicians that George brought in for the orchestral parts of the album, and that was really exciting.”

Opener Fundamentally Yours has Martin on keys and was “a lovely tune by Andy Davis,” says Warren. It’s followed by the nostalgic paean to village life Pinafore Days, written by Slater, who was now composing on piano as well as flute. Pinafore Days was also the title of the North American version of the album.

“On Stackridge I just did flute parts,” he says. “But I really liked what everyone else was doing and knew I had to up my game to have a song accepted. By the third album I was one of the major contributors.”

The power-poptastic The Last Plimsoll is a standout, with gangsterish lyrics. “Because of the music we thought the lyric should have a dark underbelly,” says Warren. “But we always tried to not be too literal and wanted to introduce strange, stream-of-consciousness phrases into the songs, too.”

To The Sun And Moon was written by Slater using a poem by his friend Deno, from his hometown of Yeovil. Abbey Road-esque, Martin’s orchestral hand is strong here, and the track finishes with Spanish guitar that leads into a Latin-flavoured, violin-powered The Road To Venezuela.

Watching George Martin work with a group of string players... the mutual respect was tangible

Mutter Slater

Slater recalls Martin’s aid in the studio with his track The Galloping Gaucho. “We started on the first chord and bashed our way through! George said, ‘I think we can make this more interesting. Let’s have a Hammond organ and a triangle on the intro; we’ll build it from there.’ He taught us about dynamics and properly using the range of instruments in the band.”

Warren’s ideas surfaced in the gentle “ecological plea” Humiliation and the McCartney-esque Dangerous Bacon. “Dangerous Bacon was a Smegmakovitch tour-de-force, named by Jim who would say that meat-eating wasn’t just bad for animals but for the eater, too.” It featured Andy Mackay on sax as Roxy Music were playing in AIR at the same time. “George or Geoff set that up – we didn’t get to know them,” says Warren.

Cresswell-Davis and his friend Graham Smith – from his time playing in bands in Weston-super-Mare – came up with folky hymn The Indifferent Hedgehog, with Martin on piano. Then comes the Slater-led group finale, God Speed The Plough. Mutter had noticed the phrase while leafing through a magazine in a hotel in Shropshire; it belonged to some verse next to an illustration of a mug of cider. “George obviously thought, ‘Here’s something I can get my teeth into,’ and came up with this fabulous orchestration,” says Warren.

“I was there for that overdub!” laughs Slater. “Watching George work with a group of string players... the mutual respect was tangible. It was done in two, three takes. Very impressive.”

We learned the possibilities of what the studio can offer. You can create magic there, but you have to pay attention to details

James Warren

With the recording finished, a political situation threw a bin lid in the works: the OPEC oil crisis – where the resources for manufacturing vinyl quadrupled in price and export was prohibited to some territories – meant the western record industry ground to a halt. The release of The Man In The Bowler Hat was delayed until February 1974, by which point the personality differences meant a different Stackridge line-up would tour the record; and to some members its release came as a bit of a shock. “We had a new manager and factions emerged,” says Warren.

“I got fed up and went back to Yeovil and got a job as a petrol pump attendant,” says Slater. Each week he got the Melody Maker, reading it from cover to cover. “One day I’m sat in the station with my feet up ’cos there’s not much to do, and I see The Man In The Bowler Hat is at No.23 in the chart! I was living at my parents, with no phone. The last I’d heard of it was at a playback in AIR studio.”

Although the studio experience had been exceptional and his childhood dream of being in a band had been realised with Stackridge, Slater was disillusioned. The band would dissolve after 1976’s Mr Mick, reviving briefly for 1999’s very creditable Something For The Weekend.

However, Stackridge did reunite from 2006 to 2015, and their catalogue is beloved by many. The Rhubarb Thrashers Club lives on – on Facebook and certain forums – with some of our favourite acts – Big Big Train, Schnauser, Steve Hogarth – being Stackridge devotees.

For Warren, the record lived up to his expectations and presented new opportunities. “We learned the possibilities of what the studio can offer. You can create magic there, but you have to pay attention to details,” he says.

“We took that on board with the first self-titled album by The Korgis, formed by myself and Andy Davis in 1979. We thought, ‘Let’s follow Buggles’ example and be a really good studio band, and not tour.’ Part of that came from The Man In The Bowler Hat.”