Through no fault of its own, the village of Cwmaman, in the Cynon Valley of Wales, probably doesn’t feature on a lot of people’s dream travel destinations. But like many of the best records unmistakably born from a particular time and place, one listen to Word Gets Around takes you there.

The once proud and formerly thriving coal mining community fell afoul of a fate well-known to many in areas where industry and shared purpose were wilfully left to rot. Working-class places where there wasn’t enough work to go around anymore became of little interest to those in power at the tail end of the last century. Things aren’t so different now, sadly. Twenty-five years ago, however, the debut Stereophonics album gave voice to those people, those places and all those lost purposes with rarefied poignancy.

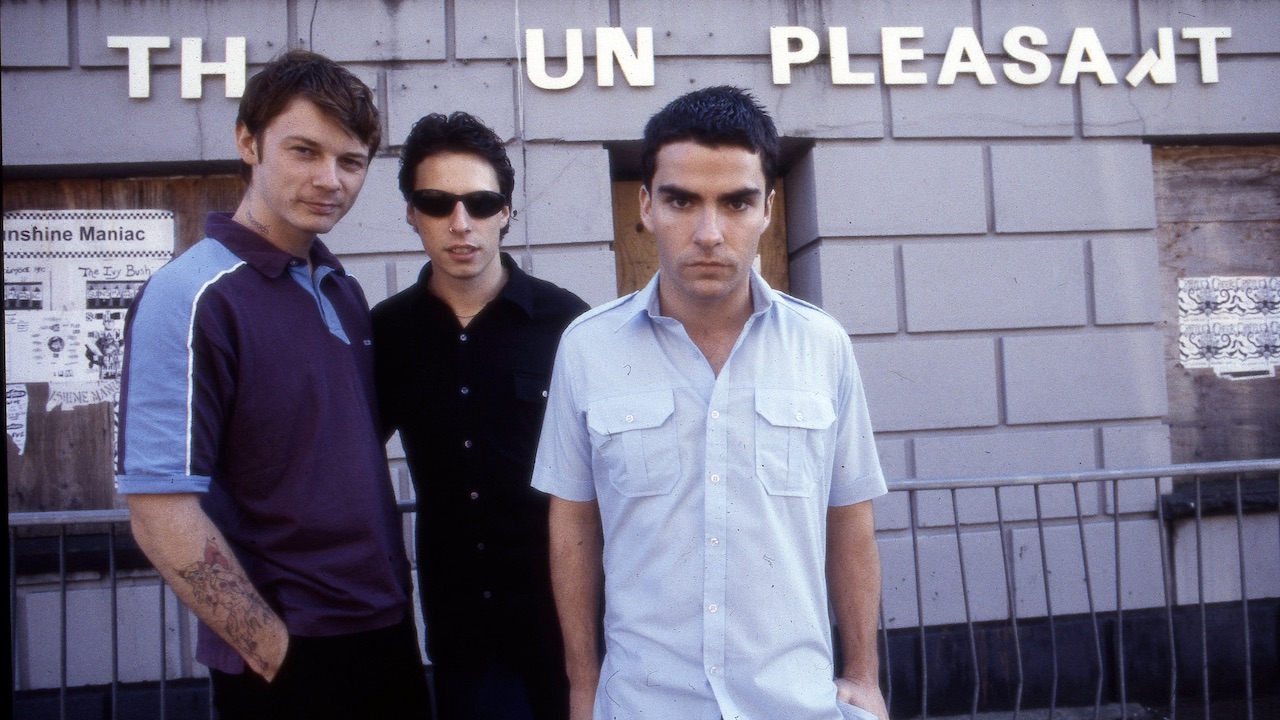

As native sons of the very streets left to pick up the pieces, they knew the realities first-hand. Frontman Kelly Jones and late drummer Stuart Cable grew up on the same one, in fact. Enlisting bassist Richard Jones and after a decade deep into their friendship, plying their wares on the dive circuit, the trio finally caught a break. In the summer of 1996, fellow Welshmen Manic Street Preachers were staking a strong claim as the most important band in the UK, propelled by their anthem-packed fourth album, Everything Must Go. Taking their up-and-coming countrymen out on the road in support of the record, the industry was sensing blood in the waters.

Soon enough, Stereophonics had successfully whipped up enough fervour to become the first act signed to Richard Branson’s newly launched V2 Records, one of 35 labels alleged to have wanted their signature. Such faith would be justified before too long.

Despite years of musical kinship forged in covers bands, Stereophonics boasted an emerging teenage star who had tales to tell of his own. And on Word Gets Around, his richly evocative stories were worth listening to.

Those who embraced the record, were welcomed into a world filled with both characters and character. The focus places Cwmaman firmly at the front and centre of its canvas, but the woes of its people prove unerringly universal. You don’t need to know the real Chaplain, Cliff Chips or Caramel Crisp namedropped in the lyrics. These local folk legends might go by different names elsewhere, but every small town and village spawns its own equivalents. They emerge from environments where everybody knows everything about everyone else, and the suffocation plays out in all manner of excruciating ways.

Kelly Jones paints the minutiae of that life in unapologetically grim and unglamourous strokes. The drama inhabits pool halls, chips shops, market stalls, and working men’s clubs. Between the lines, the sticky carpets and decades-old stench of cigarettes is almost tangible.

The former junior boxer writing those lines never pulls a punch (or equally as important, punches down). He never lets himself or his narrators off the hook either. There’s the self-knowing barb in the observations of Goldfish Bowl, for instance, “I'm drinking, sinking, swimming… thieving, cheating, beating… I'm deep in a goldfish bowl. It's sink or swim.”

He’s a product of this environment and just like everyone else, he’s doing all he knows to survive. In service to the songs and their cast of loners, drunks and hometown heroes, the music keeps things taut and economic. Even at the quieter end of the scale (Traffic, Not Up To You) the Bird & Bush production aims sky-high. If you didn’t pay close attention, you could be forgiven for thinking the whole thing’s quite upbeat other than a few exceptions.

Of course, that belies the swinging tonal extremes of self-loathing and unshakeable local pride. For Stereophonics, there seems to be an unspoken understanding in play that yes, some of these people might be bastards, but they’re their bastards. Woe betides anyone else who’d dare speak ill of them.

That’s the kind of world that Word Gets Around is mired in. Frustration and disenfranchisement abound. Infidelity and sexual murkiness are never far from the scene. The small-town rumour mill might be the only one left still working overtime. The authenticity of the band’s lived experience is never in question, however. These are dispatches from the dying embers of once proud and united communities, now tearing at the seams and coming undone.

From the “blue rinse” brigade down to the barmaids and boys out for another tear up in town, there’s generation-spanning pathos. There’s victims everywhere. It’s a record that finds heft in everyday mundanity, but they’re sad stories at the core. On Local Boy In The Photograph young people gather to drink away the pain of grieving the tragic loss of their friend. It all ends on the haunting ballad of Billy Davey’s Daughter, the titular character who threw herself off a bridge that both joins and separates this village from the next, where much of the same dramas are likely unfolding.

In many ways, history has been unkind to the band behind this debut album. Arguing the whys and wherefores of how that came to pass aren’t required here. What’s not up for debate is that Word Gets Around deserves better. It tells tales of people and perspectives rarely heard beyond the communities they originate from. For the often underrepresented from unsung, unglamorous locales, there’s comfort in recognising the similar if not the exact sames.

Outside of some wildest hopes, dreams and maybes, these were not songs destined to be sung by thousands of people while headlining music festivals. Stereophonics’ success wasn’t supposed to be crowned by number one records. Yet those things would come to pass. And when the band won the 1998 Best British Breakthrough Act at the BRIT Awards, it felt fairly seismic. The next month they gave Local Boy In The Photograph its second shot at the singles chart where it landed at number 14. The subsequent attention and momentum saw the album attain gold status (100,000 sales) in the UK. In March this year, the BPI certified the 12-song set triple platinum, for 900,000 UK sales, a fitting accolade for a record that deserves to be loved, heard and remembered fondly.

“It’s the album that defines who we are, where we came from, the one die-hard Stereophonics fans will probably say we’ll never beat," Kelly Jones reflected in 2013. “It’s that record.

“I’m still very, very proud of [it], because I still can’t believe that an 18-year-old kid wrote some of that.”