“Man, when I tell you he was cool, he was red hot. I mean, he was Steamin’.” - with apologies to Phil Lynott

If the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal had one fault, it was that it didn’t throw up too many hot young guitar heroes. Indeed, it’s a curious experience, looking back at the six-stringers who came to prominence during the ground-breaking UK rock explosion that straddled the late 1970s and early 80s.

There was Paul Samson of Samson, a grizzled old stager whose blues-rock heart was obliterated by pyro and eclipsed by the bizarre antics of hooded drummer Thunderstick.

There was Dave Murray of Iron Maiden, immensely likeable and a true crowd favourite but too cheerful and self-effacing to be a genuine contender. There was Diamond Head’s Brian Tatler, who had riffs flying out of his fingertips but whose stage presence was too studious by far.

There was Jeff Dunn (aka Mantas of Venom), who certainly looked the part but wasn’t exactly playing music. There was Graham Oliver of Saxon, who used to toss his guitar into the air, kick it across the stage, douse it with lighter fluid and set it on fire. All good stuff, but fans knew the true musician in the band was Oliver’s syrup-sporting sideman, Paul Quinn.

Then there was Steve Clark of Def Leppard.

When I first clapped eyes and ears on an unfeasibly fresh-faced Leppard – the date was June 5, 1979 at Crookes Working Men’s Club in Sheffield – they were clearly a work in progress, despite the excellence of their live performance and the undeniable potency of their songs.

The exception was Clark who, despite having turned a mere 19 years of age the previous April, had this whole rock star shtick down pat. He exuded the experience of a knowing veteran – and as seasoned observers will tell you, that ain’t something you can fake. No amount of lip-pursing and hip-shaking in front of the bedroom mirror can magic up genuine attitude, poise and self-belief.

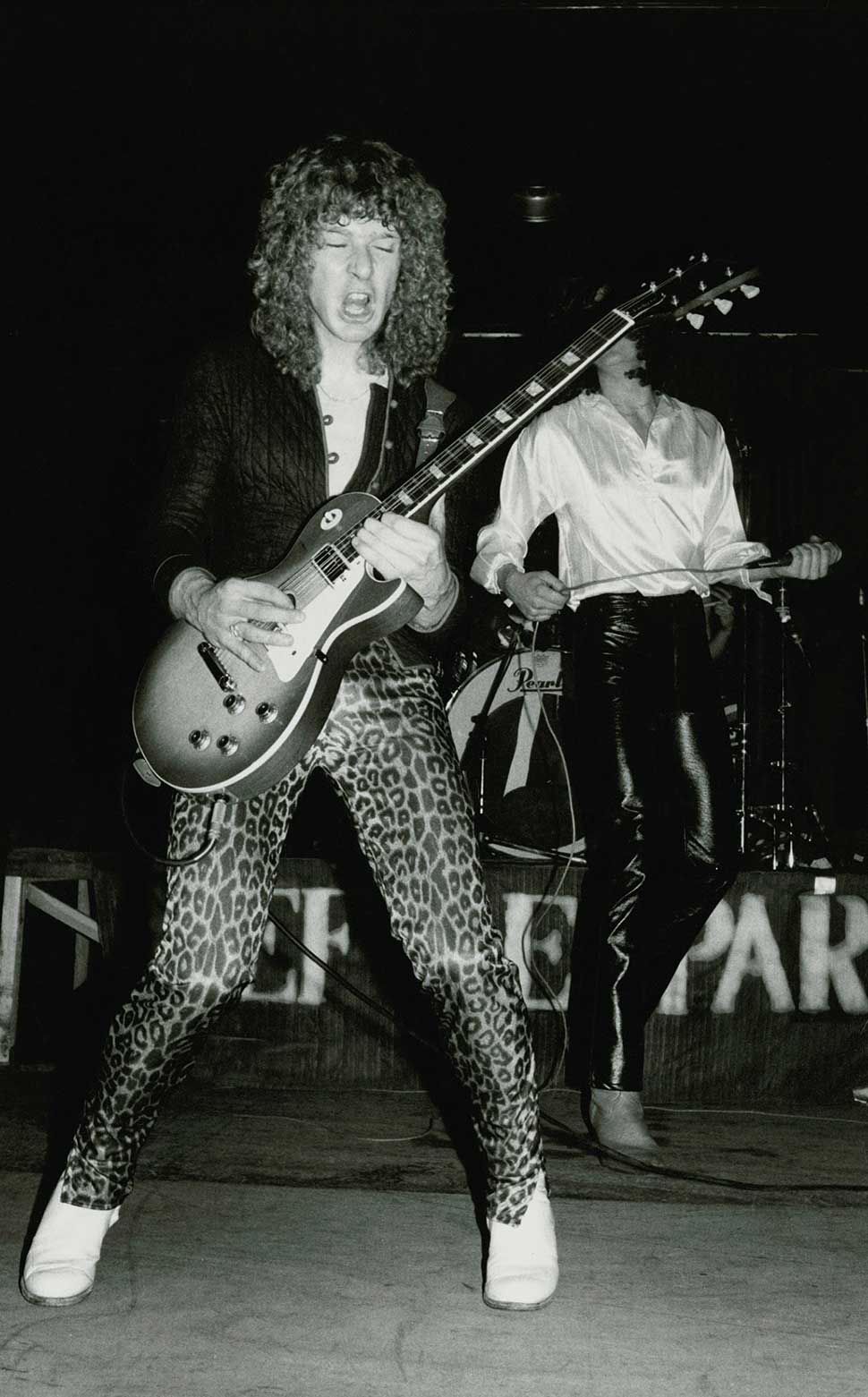

Despite his tender years, Clark was so cool. He had a feline grace about him, slinking around Crookes’ unassuming school-hall-like stage in his permed hair and leopardskin pants, guitar swaying around his knees, a big cat stalking its prey.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. When Leppard nabbed their first big tour-support slot, playing second on the bill to Sammy Hagar, I saw them at London’s old Hammersmith Odeon. From my seat in the balcony I noticed them getting in a terrible tangle as Clark darted left, right and centre, the lead of his guitar criss-crossing the leads of the other members’ instruments, until the floor resembled an explosion in a bootlace factory. The cabling was so intertwined at the finish of the set that no one could move more than a foot in any direction…

Thankfully radio mics put paid to such calamitous on-stage bondage, Leppard taking full advantage in later years when they played ‘in the round’. As tour manager Malvin Mortimer recalls: “When the curtain dropped – Kabuki style – at the top of the Hysteria show, revealing the band on all four sides, Steve would take off running like a greyhound out of the box, throwing his shapes with magnificent abandon, his long blond hair flowing behind him like he was in a gale-force wind, his signature red bolero jacket and white silk scarf all following the one-man circus of colour and style, tight white pants and thin-soled dance shoes… right knee pumping forward and upward like a Lipizzaner stallion.

"What an entrance! I would watch the audience. All eyes would be following Steve’s parade."

Clark was inspired by Jimmy Page – of course – and his guitars were slung low. Very low. That made it impossible for the five feet, two inches tall Mortimer, who started life in Leppard as Steve’s guitar tech, to tune them in the usual manner.

“I couldn’t reach the bloody tuning pegs!” he laughs. “Steve used to turn up for soundcheck and make me wear his Firebird just so he could laugh at how ridiculous I looked with the longest guitar strap in the shop.”

Frontman Joe Elliott remembers Clark’s first jam with a fledgling Leppard: “He picked up his Les Paul copy from his guitar case and put it on way too low. I just remember thinking: ‘Aye-aye, this looks good.’ He had the long blond hair and denim jacket, skinny as a rake and wearing white clogs like Brian May or Brian Robertson. He played Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Free Bird and did the whole end bit on his own. It was like: ‘Holy crap! This guy’s great.’

“He had that slightly sleazy sound, so he was very complementary to the studded, funkier style of Pete [Willis, fellow Leppard guitarist]. It was instant. I remember telling Steve: ‘Look, you’ve got the gig.’ Then Pete said: ‘Hang on, don’t you think we should discuss this first?’ So I went: ‘Absolutely not. So you want to lose this guy for somebody else? Are you kidding?’”

Off stage Clark was a humble person, with no airs and graces – except when he put them on for a laugh. Cigarette in one hand and a drink in the other, watching the world go by, he was detached but approachable – a rare but endearing combination. And as a guitarist, Clark was the riffmeister. His right hand was perfectly loose, yet his style was fluent and classy. Nobody looked and played like he did. No wonder he gained the nickname Steamin’.

As Leppard’s career accelerated ever more rapidly, relations between the hard-drinking Clark and the equally hard-drinking Willis became strained. “By the time we were touring in 1981 Steve couldn’t even stand to be in the same room as Pete, because Pete would always be the one who used up all the towels whenever he had a shower, and things like that,” Elliott reveals. “All those kinds of crappy things that ended up in Spinal Tap. When Pete had to go, there weren’t any great protests from anybody in the band.”

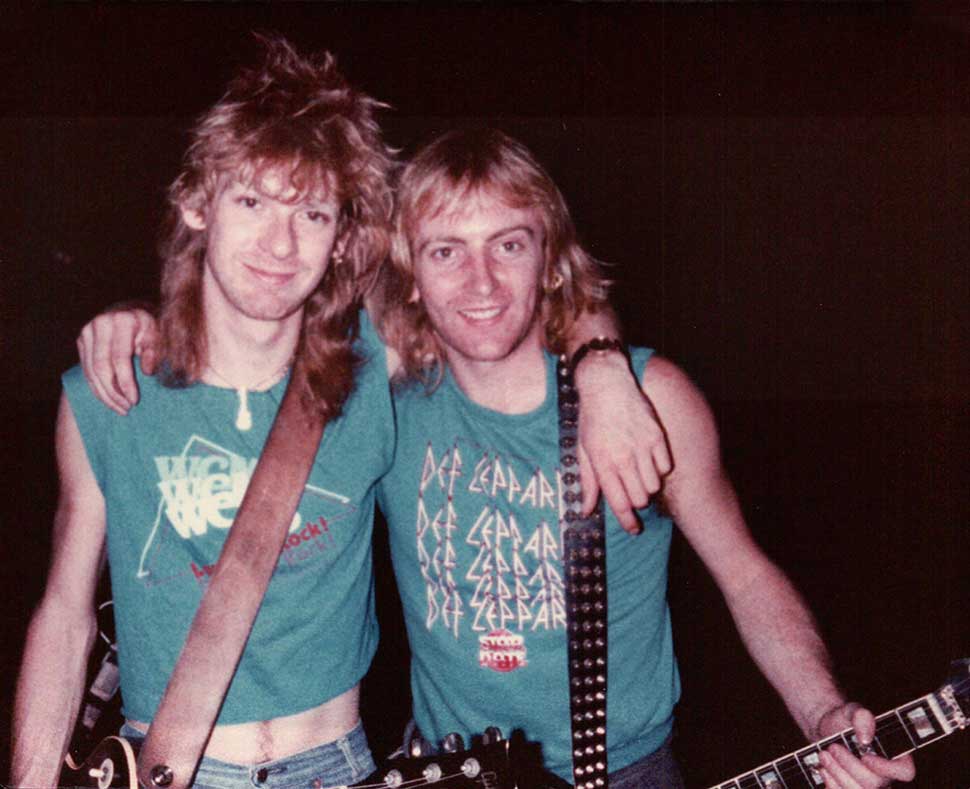

Enter Phil Collen, hotfoot from London-based Hollywood Teasers, Girl. “Steve was great,” says Collen. “Just a really warm, lovely soul, and you got that from the first time you met him. Steve had such a good vibe about him.”

Yet according to Joe Elliott, “when Phil came in, for about three days Steve was a little intimidated by him and his speed-playing. Guitarists can sometimes hate each other because of ego jealousies. But once Phil explained that he wasn’t there to outdo Steve, that he was there to complement what he was already doing, the two of them buddied up over a bottle of beer and probably about ten bottles of vodka. And that was it.”

Clark and Collen – dubbed the Terror Twins by Leppard’s road crew – were more or less glued to the hip from 1983 right up to ’87, when the latter decided enough was enough and stopped drinking. “They never fell out,” says Elliott, “but Steve lost his drinking buddy and became a lot more isolated.”

“Our relationship became something completely different,” explains Collen, “something that’s not based on going out and getting drunk. There was a whole part of my life that disappeared pretty much straight away, and that was still part of Steve’s life. So that’s when we started drifting apart.”

There is a popular image of Steve Clark as a dual personality: extrovert on stage, introvert off stage. But according to Collen, the truth was “way more complex than that. Playing in a band, being an artist, there’s an escape from reality. That was how Steve was. Being on stage allowed him to escape. Writing songs gave him that escapism.

“Steve was an artist – not just a musician,” he continues. “And usually the best artists are quite sensitive. I consider myself an artist but I’ve got a rhinoceros hide. Steve didn’t have that tough exterior. He was still a very sensitive type of personality. He took what he did very seriously. I never saw him drunk on stage. He might’ve had a drink but he kept it under control. He was very into what he did. He wasn’t going to fuck that up.”

‘It’s better to burn out than fade away’ might be an oft-used phrase, but it’s one that sums up Steve Clark’s life and career in a nutshell. He died on January 8, 1991– at age 30, during the making of the Adrenalize album. In his absence, Phil Collen had to recreate Leppard’s signature two-guitar sound alone, playing the parts that Clark would have played, as well as his own.

“We had recorded demos on multi-track, so it was really easy for me to get inside that,” says Collen. “I was sitting there with him when he played the original parts. I could relay that. But it was like playing along to a ghost. When you hear that original track and there he is, it feels like he’s alive. It’s really weird, a very strange sensation.”

To this day, Joe Elliott believes that Steve Clark does not get the kudos he deserves. “It’s because of the band he was in, it’s as simple as that,” he says surprisingly. “Steve gets due respect from the long-term Leppard fan, but generally speaking we’re not on the same level as Zeppelin, the Stones, The Beatles or The Who. But Steve went out on top.

"His last album was Hysteria, so you really can’t go wrong. If you’re going to go, that’s the one. We were the ones who were left with his legacy and who had to build it up again from scratch. We had to suffer the downside of the success of Hysteria, which we knew was going to come no matter what.”

“I remember how [record producer] ‘Mutt’ Lange summed up Steve one time,” recalls Collen. “He said: ‘Give me the thinker over the player, any day.’ That was Steve. ‘Mutt’ said there are a million session sausages – that’s what he called session players – but they have no ideas, they’re clinical. But Steve, he was a thinker. As a player and as a man.

“There was a lot going on in Steve – unfortunately, sometimes a bit too much. Steve was a work in progress. It’s very easy to talk about this after someone has passed away, but Steve really did have a lot more left to say. Steve was on this path to discovery, and booze put an end to that. If the drinking had just been a phase, if he’d have come out of it, it would’ve been wonderful.”

“Steve left behind a masterclass for anyone that wanted to write a unique opening riff and be a 24/7 rock star,” concludes Malvin Mortimer. “To think that someone once called it Bludgeon Riffola.”