The guitarist with Booker T. & The M.G.’s, Stax Records’ house band, Steve Cropper backed scores of soul greats during the 60s as well as being a go-to producer. He’s also a songwriter whose compositions include classics such as Wilson Pickett’s In The Midnight Hour, Eddie Floyd’s Knock On Wood and Otis Redding’s (Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay.

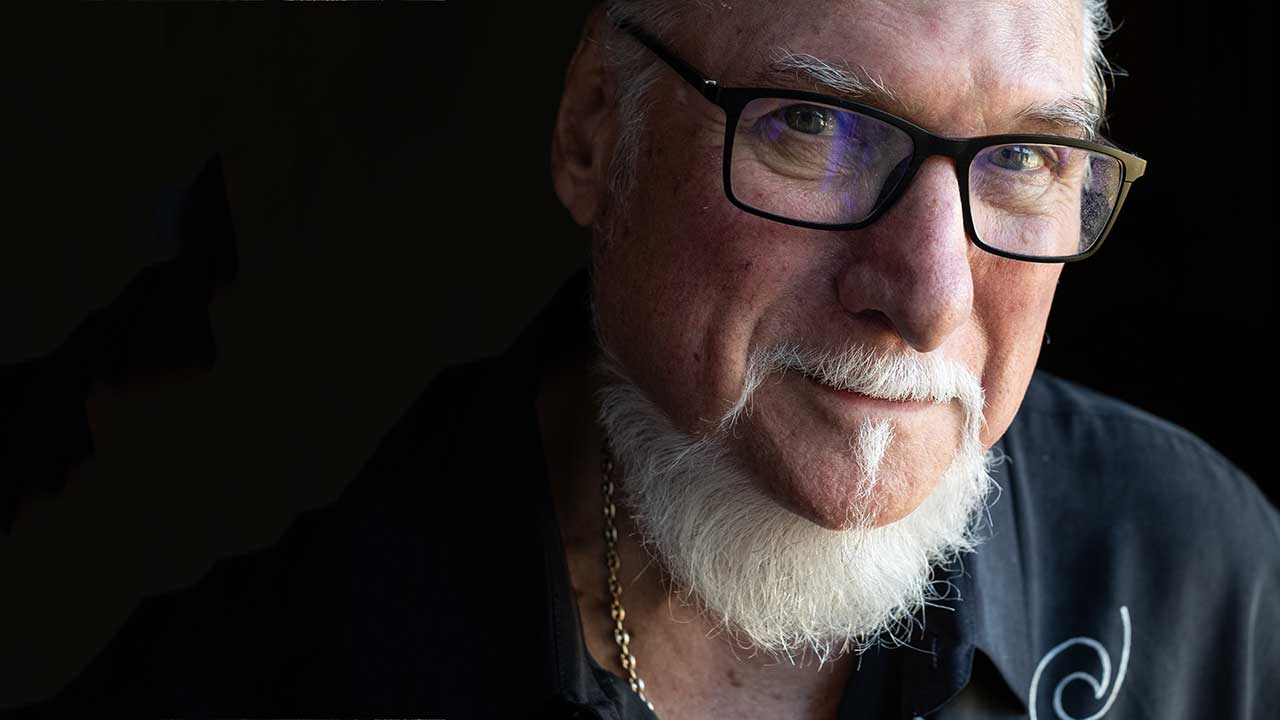

He has also done studio work with John Lennon, Rod Stewart, Roy Orbison, Jeff Beck and many more, and was a founder member of the Blues Brothers band. He’s still in great shape at 79, as evidenced by his latest solo album, the groove-laden Fire It Up.

How did Fire It Up come about?

It wasn’t contrived or conceived, it’s just something that came about during lockdown. I consider it my first real album since [1969 debut] With A Little Help From My Friends, because that was very spontaneous too.

So it wasn’t planned?

Some of the tracks were begun three or four years ago. Jon Tiven [co-producer and multi-instrumentalist] suggested we work them up and write some new ones. I told him he needed to find a singer, and he said: “We got one – Roger C Reale. Let him do a couple of sides and I’ll send them over.” I listened to them and called him back: “My god, where’s this guy been all my life?” I’d never heard anybody sing like that before. He’s awesome.

It seems that the groove is still king in your world.

I’d start most of the songs with a rhythm and we’d just go with it. For me, the groove means something. In the days of Stax I used to say, with all due respect, that if you took the singer away you still had the song, you could still dance to it.

The track One Good Turn has a particularly timeless feel.

The guitar on that is very old-style, back to the late fifties/early sixties. I think probably someone like Chet Atkins or Reggie [Young] or Chips [Moman], one of those guys, might’ve been better playing it than me.

Talking of other guitarists, what’s the story behind a young Jimi Hendrix turning up at Stax Records’ studios one day in 1964, when he was still just a session player, to ask you for advice?

I happened to be mixing in the studio that day and didn’t want to be disturbed. But the secretary came in and said: “This guy’s driven all the way from Nashville to see you.” I told her I couldn’t see anybody right now. Eventually, around five, I came out to get a cheeseburger, and he was still standing outside. I don’t know if he was looking for a job or not, but we started talking and he said he’d just played on a Don Covay session for Mercy, Mercy up in New York.

I said: “Really? That’s one of my favourite licks. Can you show me?” So I took him into the studio, handed him a guitar and he turned it upside down. I said: “Damn, man, I can’t learn it that way!” Jimi and I became very good friends.

Another friend of yours was the late John Belushi, who you backed in the Blues Brothers band. Is it true that initially he thought you were a roadie?

That’s right. He was riding in a limo with [record label executive] Phil Walden, talking about putting the band together. Phil told him not to forget me, and Belushi said: “Steve Cropper? That guy with the beard and the long hair? He’s a roadie, not a guitar player!”

I don’t know if he was kidding or not – you never knew with Belushi. But we got to be pretty good friends and hung out some. He was something else. Being in the Blues Brothers band was so much fun. We were thinking if only we could do this for the rest of our lives, but unfortunately we didn’t get to do that.

Going back to your early days, what made you follow a musical path?

We didn’t really have music when I was growing up, basically because there was no electricity. And in West Plains, Missouri, all you’d hear on the radio was stuff like How Much Is That Doggie In The Window? But we moved to Memphis when I was around ten years old. I found a gospel station on the radio and never looked back. I just stayed with it, even though I ended up playing R&B. It’s that same rhythm. It just makes you move.

Your songs have been covered so many times. Do you ever get blasé about it?

You hear so many versions that you do get a little jaded sometimes. Somebody once asked me how many times In The Midnight Hour has been re-cut over the years. I said: “I don’t know, but I’ve been paid for over a hundred and fifty versions.” That’s a lot when I think about it now, especially when it was one of three songs that Wilson [Pickett] and I wrote in one night.

British TV viewers of a certain age grew up hearing Booker T. & The M.G.’s’ Soul Limbo as the theme tune to BBC TV’s Test cricket.

Eric Clapton was the one who first told us about that. I couldn’t believe it. Here’s a trivia question for you. I get everybody with this one. Who’s playing cowbell on the intro?

No idea.

Isaac Hayes. In the studio I remember saying the song needed a cowbell. Isaac came over and said: “I can do it!” So he picked it up, grabbed a stick and played it in one take.

Do you still have ambitions left?

If there’s anybody I would’ve liked to produce that I never got around to, it’s Tina Turner. Twenty-five years ago might’ve been a good time to do it, but it’s too late now. It’s never too late! I think it is! [laughs] People ask when I’m going to retire, and I say: “When they can’t wheel me up to the microphone any more.”