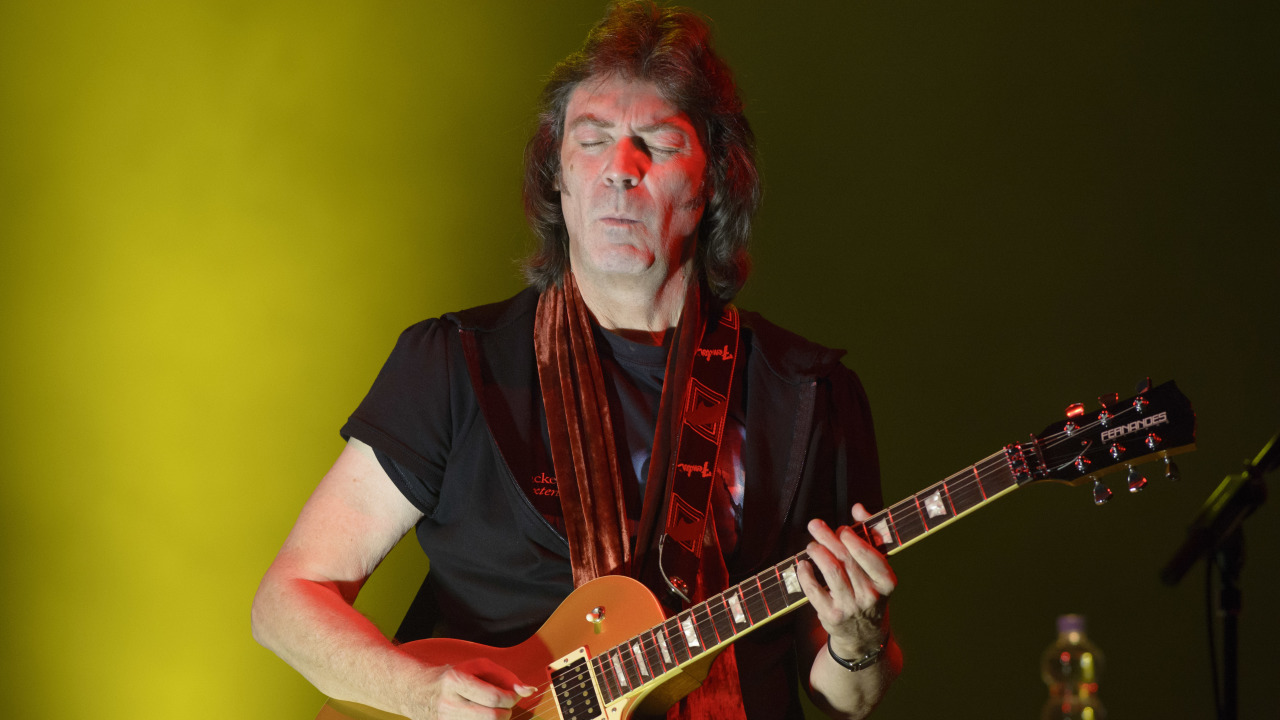

It’s quite a landmark for a musician to get into double figures for the number of albums they’ve released. Steve Hackett needs no introduction, of course, but he’s about to release his 24th solo. Note: that doesn’t include the baker’s dozen of Genesis albums, nor does it include any live albums or indeed any collaborative releases. To say the man is prolific doesn’t really do this level of output justice.

“If I add up all the albums I’ve ever been on with everybody, it’s probably about 70,” Hackett says, measuring up his 40-year career. “I don’t think there’s any secret to it. I start work on things and then other things come along and some projects have to be put slightly to one side while the rest of the world catches up. There are other things going on at the same time as any one particular project.

“While I have this album coming up in a month, I’m working on a live DVD that we did at Shepherd’s Bush last year [Live Fire And Ice, released in 2012],” he explains. “There’s always another project in hand. I tend to be thinking ahead by at least one or two each time.”

Having started recording as a 20-year-old with Quiet World in 1970, Hackett understands that he’s an elder statesman of the progressive genre. He may have created a lot of music, but the desire to create more still burns deep, partly because – as he readily admits – he’s getting on a bit.

“I talk to contemporaries about this sort of stuff, and everyone who’s of a certain age is aware that the clock is ticking, and that we’re all potentially in the drop zone so you’ve got to watch out for that,” he says, rather matter-of-factly. “I want to get as much out of myself as I can in the remaining years. It’s morbid but it really gets you proactive.”

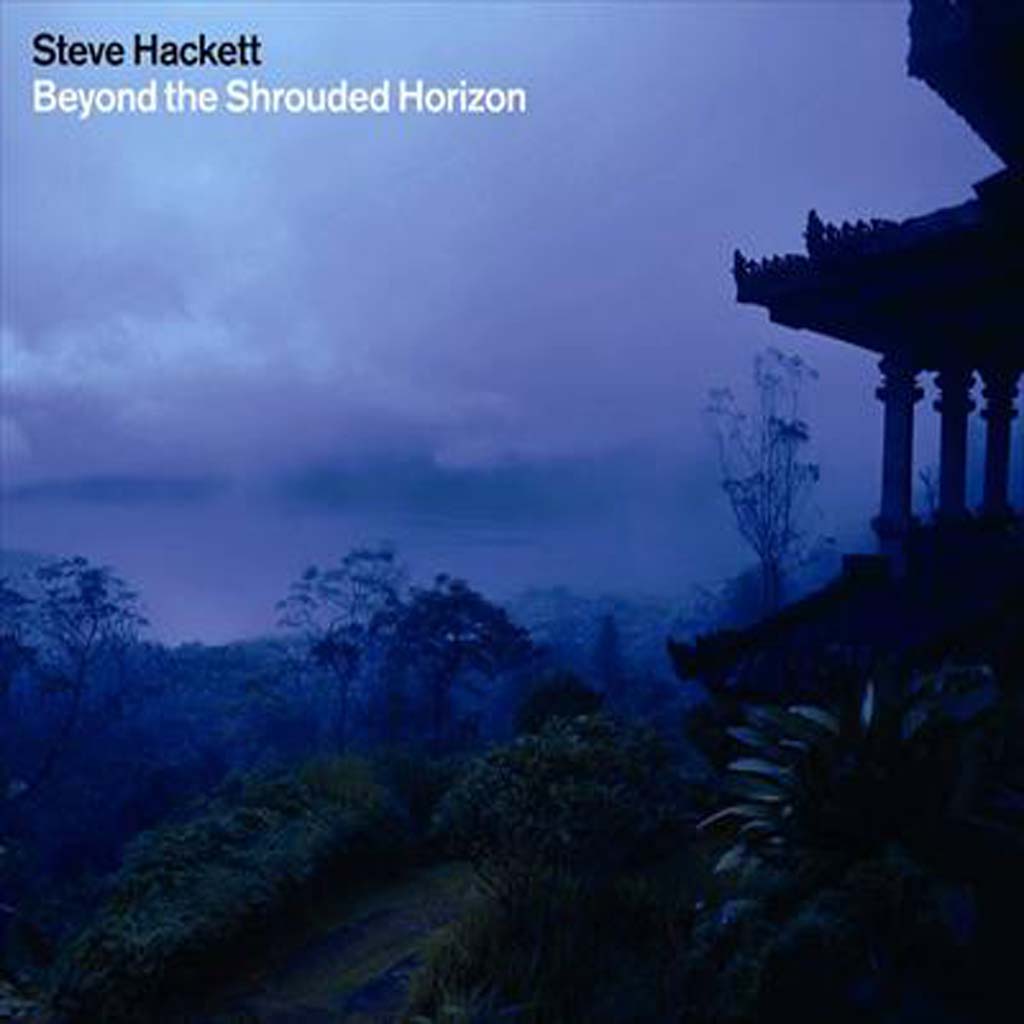

The latest album, Beyond The Shrouded Horizon, really is testament to his ideals. Coming less than two years after his last solo effort, Out of the Tunnel’s Mouth, it’s an hour-long, 13-track exercise in diversity, and Hackett revels in his place as a progressive musician now as much as he ever did.

“The first solo album I did in 1975 [Voyage Of The Acolyte] was perhaps more typically progressive but the album I did after that [1978’s Please Don’t Touch] featured a lot of black artists; white Americans; English; Europeans,” he says. “So I was already headed towards the level of diversity that would almost be seen as a sampler album. At one time, CBS in the 60s were releasing sampler albums that would have Leonard Cohen on the album along with Simon & Garfunkel, Grateful Dead and a track by Tim Rose or Roy Harper.”

“I thought it would be nice if I could do that sort of thing myself and have flexible personnel from track to track,” Hackett explains. “The [Charisma] label boss, Tony Stratton-Smith, thought it was both the album’s strength and its weakness, so there is a fear of a lack of identity, but I figure that these days if I am the main singer and there’s enough guitar work, there will be an identity on it and then I can afford to be as eclectic and diverse as much as possible.”

While Hackett is clearly interested in the development of new progressive music, you get the feeling that his timeless records rise above the rest with inimitable, peerless ease. As a man who has played this type of music his whole life, he is able to marry an acute knowledge of the history of the genre with its current state of affairs.

“These days it’s synonymous with impenetrable time signatures and longform pop, but having been involved in lots of those things in the past I’m very aware how a simple song is also desirable,” he says, illustrating his preference for shorter, more accessible songs. “I don’t mind things that are long, provided the things within are easily digestible. I do like music that uses contrasts to good effect - – something that allows wide dynamics and a certain kind of tension and release; if you have the peaceful passages between so that people have the chance to draw breath and have some spacious passages. Nylon guitar is perfect for that, especially for slow things. It’s like having a cool drink or going for a swim.”

He demonstrates this coolness in the gently strummed 44 seconds of Wanderlust. In the most stark of contrasts, however, is album closer Turn This Island Earth. Nearly 12 minutes of deep, dark menacing prog rock that is so densely orchestrated that even the computers couldn’t keep up with what Hackett was writing.

“We were severely taxing the resources of the computer, because that thing is upwards of 300 tracks – we had to update technology as we went,” he laughs. “Rather frustratingly, I couldn’t listen to it from front to back for quite some time.”

Not only is it the longest song on the album by quite some margin, but Turn This Island Earth is also the most complex. With time signature changes and an extensive list of instruments, there’s more than enough to keep you occupied. Coming at the end of an album filled with songs that are slightly more conventional, perhaps, it’s a pleasant and welcome surprise – but it’s a style that is purposefully marginalised.

“I tend to like people to be able to tap their foot through things these days,” he says. “I always get worried that a lot of the earlier albums that I did, because of the use of 5⁄4 contrasting against the bars of three and six, there was always the danger of having too much punctuation and not enough statement. I always like to think that if the statement can be digested, that would be nice and easy and the complexity comes in with how these things are joined up.”

The craft and care that has gone into the creation of Beyond The Shrouded Horizon is clear, but what were the major inspirations and the thought processes behind the songs?

“I tend to see music visually, and this album makes me feel like I’m on an ocean liner or a hovercraft scudding along. I get to another moment – as if it was a world of sound – and I see an inlet or an island there and I’ll just pull into harbour here… and then we’re off again for another adventure,” he tails off. “It seems that most of what I do is deliberately escapist. There’s lots of fantasy in the album, but I’m also keen to rein it back into the world of reality as well.”

“The album itself has got the idea from Celtic coracles to futuristic spaceships,” he explains. “The title itself, Beyond The Shrouded Horizon is saying that if only you could look into the future; if only you had a crystal ball; what is to come from that journey? It’s very much a romance of places, but not just an un-peopled landscape – it’s also what happens to those people within that landscape.”

The balance between surrealism and actuality is always a fine one in the arts, and for every song that goes too far one way, there’s always another song that goes in the other direction, and the gently lilting Looking For Fantasy is certainly that.

“I try to make it about relationships, and this is a nostalgic look at a 60s flower child,” Hackett explains. “But she’s a composite of lots of people that I knew, many of whom fell by the wayside, and they’re not of this earth any more. But it was that kind of optimism, mixed with naivety with the mindset of 60s flower children.

“I tend to see music visually, and this album makes me feel like I’m on an ocean liner.”

A song that marries relationships, escapism and optimism exceptionally well with a tune that people will be able to tap their feet to is Prairie Angel – a wonderfully casual slice of prog which slides down the fretboard into a foot-stomping slab of heartland rock. Interestingly, Hackett cites Jack Kerouac’s work as an influence for this one, in particular it was the moment when the semi-autobiographical Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty drive their car into a ditch in chapter eight of the classic novel On The Road.

“They’re pulled out of it by a farmer while his daughters are looking on. They agree afterwards that one of the girls is the most beautiful they’ve ever seen. We’ve got the wide open spaces and a pioneering feel with banjo and 12-string, but I thought: ‘Let’s set that in the 1800s,’” he explains. “So there’s this mixture of cultures and it’s something this guy is trying to deny, but he realises he’s got to go back to that place. It’s a little in the style of Bob Seger, where the vocal phrases are desperate, emotional salvos that end very quickly, and you feel as though you can’t wait to run with it.”

Something that is certainly new about the latest album is that that his writing partner and muse Jo Lehmann – sister of bandmate Amanda - is now his wife. Together they work on a lot of lyrics and ideas together – including the conception of Turn This Island Earth in a Starbucks coffee shop. Along with Roger King, there’s quite a team in place, and the practicalities are not lost on Hackett.

“It’s like working with a band, but without having other people vetoing the things that I like the most myself,” he tells us. “I think the danger with bands is that they can often come up with some really great things, but there might be a really good idea that doesn’t get done because of the politics. This circumvents the politics that bands get ensnared by, so it means that there’s more music coming out with more frequency.”

It’s a little bit like a dictatorship,” he laughs, “but it’s a very benevolent one, and I want the input, where I listen to everyone.”

Hackett laughs even harder at the suggestion that his other half might be putting her foot down a little bit firmer now.

“I think she’s equally driven as me. She’s very work ethic-oriented. and sometimes I have to say to her: ‘Slow down. We need to have time to sniff the flowers and take in the air’. Sometimes I have to make her down tools.”

Famous for being a thoroughly nice chap, Hackett ends our conversation on a typically humble note. “It’s a team that makes the album,” he says. “Without Roger’s input in the album, as well as Jo’s, it wouldn’t have come out the way it did and everyone who plays on it gets to influence it as well. It’s a solo album in name only.”

This was published in Prog issue 20.