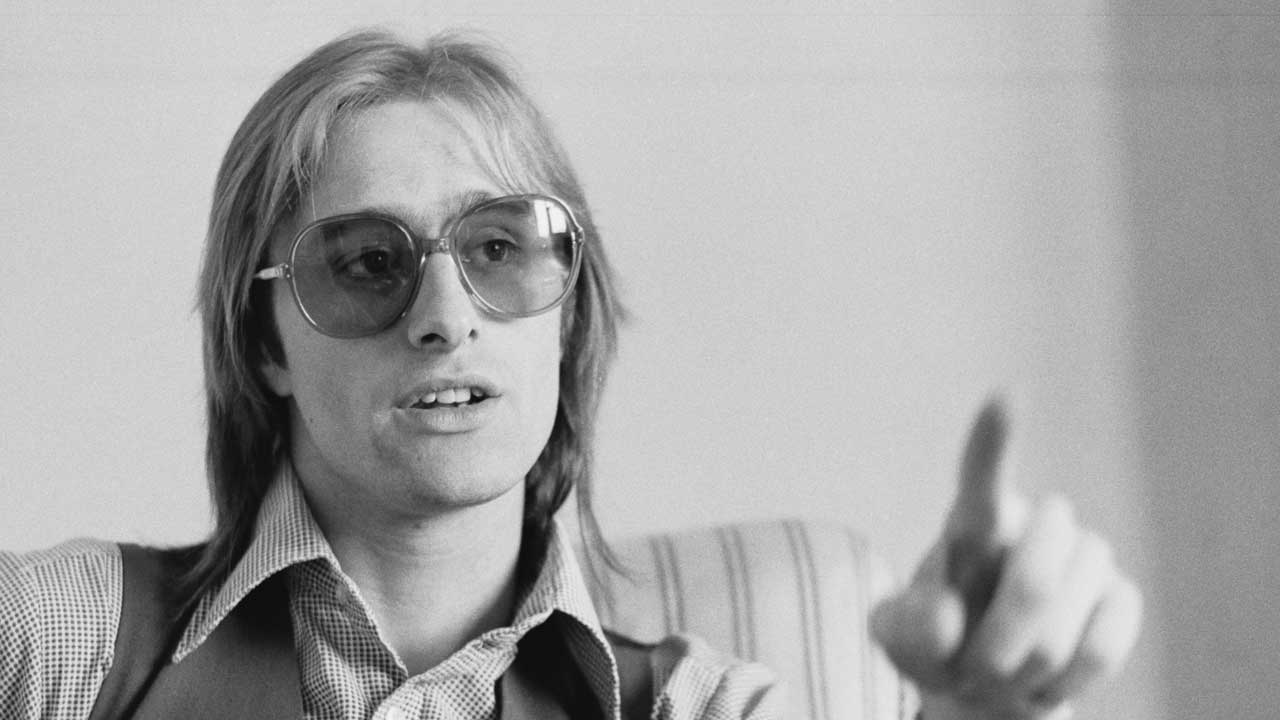

In 2004, Classic Rock's Geoff Bartion sat down with the late Steve Harley, a man he'd first interviewed nearly 30 years earlier. They talked about the singer-songwriter's difficult childhood, his unlikely route to fame, the breakthrough and breakup of his band Cockney Rebel, his return to the spotlight, and why he really hates journalists.

You always remember the first time, they say, And for me the memory is etched deep. It was heart-thumping and pulse-pounding; eye-watering and spine-tingling; uplifting and inspiring. All at the same time. I don’t mind admitting that I began hesitantly, and it took me a while to reach my goal. There was plenty of hard work and honest sweat into the bargain. But when I finally managed it, I couldn’t believe it. I was breathless with satisfaction. Truly, it was a life-affirming experience.

Yes indeed, it was a mightily momentous occasion: my first front-cover story as a music journalist. The issue in question was Sounds dated April 26, 1975, and the artist was a certain Mr Steve Harley.

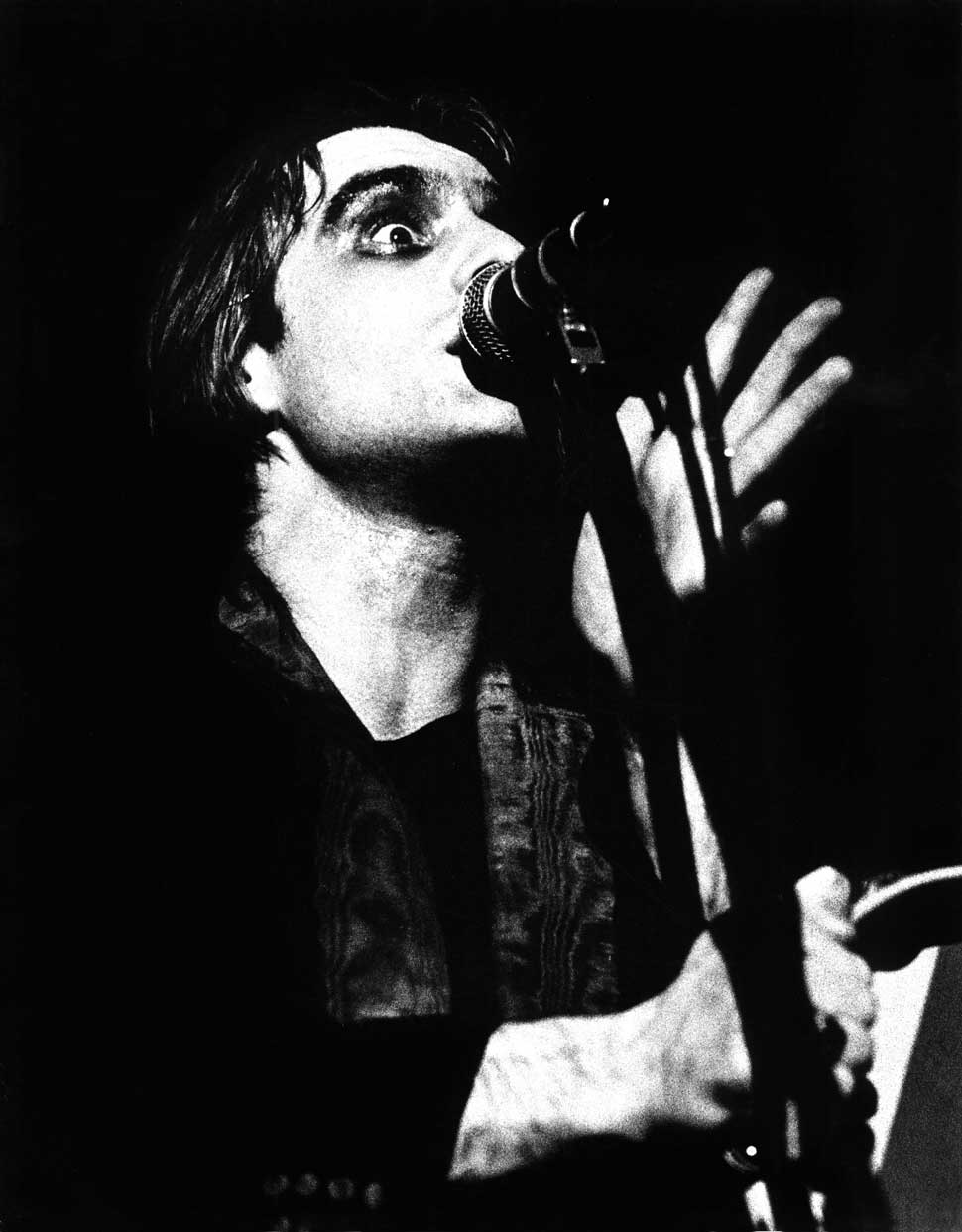

The page-one photo of the Cockney carouser – grabbing his mic tightly, mouth wide open in an agonised ‘O’-shape – was accompanied by the oh-so pertinent headline: The Rebel Who Played The Game & Won.

As we head toward the middle of the first decade of the noughties, it’s easy to underestimate the impact Steve Harley and his swashbuckling Cockney Rebel cohorts had when they came out of nowhere and released their debut album, The Human Menagerie, back in ’73.

“We were young and full of dangerous ideas and adventure, ready to experiment without consideration for the consequences or costs,” Harley says in the sleeve notes to …Menagerie, now reissued on BGO Records.

Certainly, self-belief oozed from Harley’s every pore and pulsed through even the narrowest of his veins. He predicted success in his first interview; he laid carefully calculated plans to gain stardom; he manipulated people like chess pieces; he treated the music biz as if it were a complicated game. What’s more (to continue the chess analogy) Harley was an insensitive tactician, not hesitating to sacrifice a few sluggardly pawns along the way.

In the early 70s, the risks for a young, outspoken artist such as Harley were enormous. But the great surprise – particularly to those wasters on the NME, upon whom the singer declared all-out war – was that he lived up to his no-nonsense proclamations, and that he managed to secure his slice of notoriety in a relatively short space of time. Checkmate: with a self-satisfied, triumphal sneer.

“Was it really like that? The seventies seem like a dream,” Harley rationalises today, as we talk backstage before one of his acclaimed electro-acoustic shows at the Mick Jagger Centre in Dartford. “But yes, I remember being confident at the time. Extremely confident. I expected shows like Wembley to sell out, I expected to sell out three nights at Hammersmith, I expected to sell out shows all over Europe, I expected to sell thousands of records. I expected it.” He draws a deep breath. “I put on a big show – it wasn’t Genesis or Pink Floyd, but I always had something going on. But I also did a lot of drugs and I drank a lot, and what you get is a hazy memory for detail. Not good. Not clever.”

Now, Harley insists, “I’m much more humble. It amazes me that people still care so much after all this time. It’s really a great feeling. All I want is an audience.”

Steve Harley certainly made a major impression on yours truly when …Menagerie first arrived in the shops. I embraced the album with obsessive enthusiasm. I had been too young to succumb to the early attractions of Marc Bolan and David Bowie, but at last I’d got a hero of my own: the fey, off-kilter and self-absorbed Cockney Rebel mainman. To me, the vision of a wild-eyed Harley preening the fox-fur collar of his leather jacket on Top Of The Pops is every bit as enduring as Noddy Holder and his mirrored hat, or Roy Wood and his crazy facepaint, or The Sweet and their Red Injun head-dresses.

No doubt about it, Harley and his group were a brand new thing in futuristic satin suits and bow ties, and one of the members (bassist Paul Jeffreys) even had a tiny heart painted on his left cheek, which I thought was rather endearing. And the fact that Cockney Rebel didn’t even have a lead guitarist was neither here nor there.

On first examination in the early 70s, Harley’s music sounded unremarkable: it was understated, jangly and folk-tinged. But closer study revealed it to be strangely subversive: it was jagged and edgy, with the singer’s highly mannered, nasal voice augmented by the abrasive, nails-across-a-blackboard sounds of violin player Jean-Paul Crocker. A stream-of-consciousness conundrum of quirky lyrics added to the attraction: ‘So now we’re on a death trip/Listen to the blood drip/Oozing from a curled lip’ (Death Trip). ‘You can shuffle your hips or M-M-Mae West your lips’ (Mirror Freak, Harley’s affectionate tribute to his friend Marc Bolan). And best of all: ‘My only vice is the fantastic prices I charge for being eaten alive…’ (My Only Vice).

Naturally, it didn’t take long for Harley’s ego to break out of its cage and savage all who stood in its path: “I hear bands who support us say that I won’t let them use my drum rostrum or PA, things like that,” Steve told me in that interview back in ’75. “Why should I? I’m antisocial. I don’t go to clubs. I never asked for any favours on the way up. I’m not nasty to them. If they keep out of my way, it’s all right. I’ve been a right bastard to get where I am now.”

Steve Harley was born Stephen Nice in Deptford, South London, on February 27, 1951, the second of five children. In the late summer of 1953 he contracted polio during a countrywide epidemic of the potentially fatal disease. He was afflicted in the right leg, which accounts for his limping gait today.

“I spent a total of about four years in hospital between the ages of two-and-a-half and sixteen,” Harley recalls. “I had a couple of yearlong stretches, plus there were loads of odd three- and one-month periods. I came out of hospital for the very last time after surgery at the beginning of nineteen sixty-seven.

“In those days,” he explains, “you’ve got to remember that if you needed physiotherapy they kept you in hospital for months. Now you’re kicked out on to the streets almost immediately – but you seem to get better naturally. The surgery is also much more accurate now, less damaging, not as painful, and you heal quicker. So it was all physio and recuperation and months in hospital in those days. Especially for children, I think. So yeah, I spent nearly four years of my life in Queen Mary’s Hospital for Children in Carshalton Beeches, Surrey.”

It was when Harley was aged 12, while in hospital recovering from another major operation, that he first heard Bob Dylan and realised that his life was likely to be preoccupied with words and music. A Christmas 1964 children’s-ward visit by The Rolling Stones – who were on a goodwill PR jaunt – reinforced this brave young boy’s determination.

Of course, all the years in hospital left their scars. In fact when Harley looks back on those times now he often talks about himself in the third person; he calls himself ‘Little Steve’.

“I do say to the audience sometimes, ‘You don’t want to hear songs about, hey, life’s great for me, I’m really happy; you don’t want to hear that in a song, do you?’ Of course you bloody don’t. Great art is normally when an artist is young and hungry, full of angst; the creative juices are pumping, when you think the muse is forever on your shoulder. So increasingly these days I find myself thinking about Little Steve, and how he was affected by those years of… solitary confinement, almost.”

Harley finds that the smallest incident can trigger memories of Little Steve. Like when his wife, Dorothy, once tried to tidy up his study (“Which is a bit of a tip, I’ll admit”) back at their home in the Suffolk countryside.

“I don’t know why, but something cracked inside me and I was furious,” he discloses. “When I hit the roof about it I had to explain it to Dorothy this way: I spent four years on and off in hospital as a young boy, and everything I had in the world was in a wooden cabinet that sat there by the side of the bed. You leaned over and you opened the cabinet, and there was your world – with a bowl of grapes on top. And a bottle of Lucozade.

“That was my life in there: my books, my paper, my pens, my pencils… that was all I ever had for a long period of my life. And it made me think, ‘Look, that’s my private space, people mustn’t invade it’. That made me protective of the most important, tiny things in my life. I can’t shake this. I can go to therapy, but who needs it? I know more about life than any therapist I’ll ever meet. But it is there, and it’s from the childhood.”

Between the ages of five and 11 Harley was a pupil – on and off – at Edmund Waller Primary School in Waller Road, New Cross, London, a short walk from his parents’ flat at Fairlawn Mansions, New Cross Gate. His first guitar, a Spanish, nylon-strung instrument, was a Christmas gift from his parents when he was 10. He took classical violin lessons from the age of nine to 15, and played in the school orchestra at his secondary school, Haberdashers’ Aske’s Hatcham Grammar, in Telegraph Hill, New Cross. But he left school at age 17 without completing his A-Level exams.

In spring ’68 Harley got his first full-time job, as a trainee accountant at the Daily Express offices in the famous art-deco ‘Black Lubyanka’ building in Fleet Street – in spite of gaining just 9 per cent in his mock O-Level maths. Needless to say the school declined to enter him for the exam proper. But Harley’s heart was set on a career in journalism, and he eventually signed indentures to train with Essex County Newspapers in Colchester.

After three years working for the group, he moved back to London to work for the East London Advertiser, then based in Mile End Road, in the heart of London’s East End. (One of his contemporaries was Richard Madeley, of Richard & Judy TV fame. It was Madeley who actually took over the desk relinquished by Harley at the East London Advertiser in ’72. “If you hadn’t given it up to become a rock star,” Madeley once told the singer, “I may never have got my chance to become a reporter.”)

Later, Harley would use his journalistic background as a tool to rile certain sections of the UK music press – in particular the pretentious pen-pushers at the NME who had taken a pathological dislike to the Rebel rouser.

“God knows what overtook me,” Harley sighs. “I was young, arrogant, I had been a reporter and I had been trained by two very good, really top-notch news editors, really top men. I still keep in contact with several of my journalistic pals from those times today. They’re much better company than musicians, so witty and worldly.

“So it was hard for me to read pieces about me in the music press that were poorly written. The problem with most of you [music journalists] in the early seventies… you were wicked, evil, you only came alive when you were taking the piss, whereas really great writers can write really great stories without tearing people apart and humiliating them.”

Charles Shaar Murray was a particular hate figure of Harley’s: “It didn’t help when I referred to some of the music press as failed drummers, or failed harmonica players in Shaar Murray’s case. He wrote some shit about me in the NME, so I pinned him to the wall at the Reading Festival.”

Harley claims he’s a mellower man these days – he has even managed to make the peace with Shaar Murray in recent times (“We’re both wiser now”). But he’s still got an unnamed writer from Q magazine in his sights: “I had this album in ninety-three called Yes You Can. It ain’t my finest collection, but it ain’t a bad one. It came out through Music For Nations. Q gave it to some bozo to review who is now writing in Fleet Street. He’s been on telly a few times doing cheap and cheerful travel reports – free holidays for him and his family. And he will be in a room with me one day – and he will have to answer to me.

“This guy decided to stick a knife into Steve Harley – God alone knows why. For a review that he got paid something pathetic like twenty-five quid for, he wrote that I’m ‘still apparently quite popular in some far-flung corners of the planet’. How dare he diminish me like that? He’s a shit. And I know his name and I know what he looks like – but I don’t think he knows that I know…”

Harley throws his arms up in exasperation. “Why should I put up with shit? This is a grumpy old man talking, I understand that, but I’ve still got a twinkle in my eye. You could say why not let it go. But this guy single-handedly, in the most important reviews section in this country, ruined that album’s chances. He doesn’t write about music now, by the way. His column in one of the nationals is a really second-division diary piece – and I’ll tell him that when I see him, too. I’ll get him. I talk a good fight, ha-ha!”

Harley began his career in music ‘floor-spotting’ (singing for free as a member of the audience) in London folk clubs in ’71 and ’72. He performed at Les Cousins, Bunjie’s and The Troubadour on nights featuring John Martyn, Ralph McTell, Martin Carthy and Julie Felix, all leading lights of the London folk movement of the time.

Harley later joined the folk band Odin as rhythm guitarist and co-singer, which was where he met the first Cockney Rebel violinist, Jean-Paul Crocker. However, the folk scene proved a little tame for Harley (“I couldn’t stand playing to greasyhaired beatniks,” he was reported as saying) and, as he was constantly writing songs, he formed Cockney Rebel as a vehicle for his own work.

He experimented with different line-up permutations, eventually opting for a band without guitar, an instrument which at the time, he said, he found derivative and despicable (just don’t tell Jim Cregan). For the …Menagerie debut album, the Cockney Rebel lineup was completed by bass player Paul Jeffreys, keyboard player Milton Reame-James and drummer Stuart Elliott.

“I cleaned floors to help boost my dole money,” Harley declares. “I’d long since given up proper employment and I spent all my time busking it in the London subways, people-watching and writing. I polished a parquet floor for a famous model. She wore grey, and looked quite severe and beautiful as the smart set of pre-war Germany would have looked, and I got the song What Ruthy Said [the second track on …Menagerie] from that day.”

In ’72 Cockney Rebel signed to EMI for a guaranteed three-album deal: “No options or get-out clauses which litter the contracts of today,” Harley insists, “just plenty of time to develop.” Or as he put it to me in that interview in ’75: “Before we actually signed a recording contract, there were a lot of big-name companies after us. But I knew we could get what we wanted. I haven’t been in the music business very long, but I’m not stupid.”

The Human Menagerie was released in November ’73. Disappointingly, it was a slow-seller, and the single from it, Sebastian, which was widely tipped to be a freak hit, flopped – at least in the UK. Even today this mysterious, baroque epic remains a mainstay of Harley’s live set. But at almost seven minutes in length, no one really knew what to make of Sebastian way back then. With lyrics such as, ‘You, oh-so gay, with Parisian demands, you can run around’ the song eventually became a ‘pink anthem’. Today Harley prefers to describe it as “a gothic love song”. ‘

…Menagerie was recorded in June and July ’73 at Air Studios, then on the top floor of the Peter Robinson department store at Oxford Circus in London’s West End. It was about three-quarters finished when producer Neil Harrison said he would like to overdub an orchestra and a choir on to Sebastian and the album’s closing track, the bleak and mesmerising Death Trip.

“I was just twenty-two years old, I had Geoff Emerick engineering, who worked with The Beatles, and suddenly, for my three-chord Sebastian, a forty-odd piece orchestra sits down,” Harley gasps. “It was extremely moving, it tore me up. It was cathartic; it would change you, wouldn’t it? I’d busked all those songs, I’d written all of …Menagerie and half of [second album] Psychomodo before I got a record contract. I was on the dole for a year, living near Marble Arch and busking the subways, and now I’ve got this bloody orchestra in front of me.”

Despite apathy in the UK, Sebastian was a big success in mainland Europe: “In Holland or Belgium it was number one for so long they put it above the chart, they called it a super-hit so they could have a new number one after about fourteen weeks or something, and in Germany Sebastian earns me more airplay than [’75 mega-hit] Make Me Smile. It’s played a lot. So it was a big hit in places, enormously so, but in the UK, no.”

Cockney Rebel made tentative steps out on to the British club circuit and, hopefully, the Sebastian single was re-released. Comparisons between Harley and David Bowie began to surface for the first time – people discovered that both at one time did a residency at the Beckenham Three Tuns; both started off a tour at Aylesbury Friars; both wore make-up and looked glamorous – Harley getting his fancy togs from Granny Takes A Trip down the King’s Road.

The parallels would continue, but Cockney Rebel – by this time branded ‘Cocky Rabble’ by an increasingly infuriated NME – were steadily building up a staunch following. The band’s gigs were bizarre affairs. Harley, often dressed like some refugee waiter from The Savoy, in black tails and satin bags, proved himself a spellbinding performer. The group played a showcase for European press and promoters at the Rainbow Room in Biba’s, the eccentric Swinging 60s fashion store in London’s Knightsbridge – and it was a perfect fit.

People also started to speculate about who the real Steve Harley was, and they tried to peel away his Cockney Rebel bravado. For the man was (and still is, to a certain extent) a puzzling but enthralling character. As I put it in my review of Harley’s Dartford show in Classic Rock issue 67: ‘He has a unique presence; fragile and vulnerable, yet bad-tempered and belligerent at the same time.’ But to tell the truth, for most of the 70s it was well-nigh impossible to tell whether Harley was serious or not. Perhaps not. Still, he had great charisma and the Rebel yell was coming on strong.

Harley made good journalistic copy. In interviews he was outspoken, determined, cocky, controversial. He made a fair number or enemies as he bluntly and contemptuously put down the music business and all it stood for. He disregarded all convention; he wanted the whole world to know who he was, and how and why he was destined to succeed.

“I went through a lot of people and heartbreak,” Harley once admitted, “but I know I’m going to make it.”

The breakthrough in Britain came with the March ’74 release of the single Judy Teen. Record buyers eagerly embraced this weird, staccato-sounding, rinky-dink pop creation. They became accustomed Harley’s affected enunciations and began to find Cockney Rebel’s avant-glam stylings strangely appealing. Judy Teen rose to No.5 in the charts.

Harley admits: “What was a big shock to me, in retrospect, was that EMI said, what do we do now, there’s not another single on the album. But if you play ….Menagerie, for Chrissakes, you’ve got What Ruthy Said, maybe Crazy Raver, which is a bit childish, admittedly… but you’ve certainly got Loretta’s Tale. I can’t believe they didn’t think of releasing one of them as a single after Sebastian, something a little more mainstream. But anyway, I went away and wrote Judy Teen, came back and said to the EMI guys, I think I’ve done it.”

Psychomodo, the second album, built up advance sales orders of 12,000 before it was released in June ’74. Sounds – always quick off the mark to spot a fast-rising trend – scrambled on board the Cockney fruit barrow and branded the Rebel ‘the fastest rising band of the year’.

As ‘sold out’ signs began to appear outside Cockney Rebel gigs, Harley said at the time: “We’re doing the same live circuit that Bowie did in seventy-two, but we’re doing much better. It’s happened so quickly, but it hasn’t affected our, or my, ego. It hasn’t even boosted my morale. It hasn’t surprised or mildly shocked the band. Everyone else was shocked, but they should have had faith in me in the first place.”

In his famous song Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie sings: ‘When the kids had killed the man I had to break up the band.’ In late July ’74, in Manchester, at the end of a headlining tour, Steve Harley did the exact same thing. Cockney Rebel had been together for just over a year, and they had just become the biggest band in Britain. So Harley split them up.

“I didn’t disband it,” Harley insists today. “I’ve dined out on that story ever since, but it’s not true. I’ve started to speak out about this lately, I’ve decided that the truth should be told.

“What happened was, one of the Cockney Rebel band members [Milton Reame-James] came to see me after a forty-four date British tour, which was entirely sold out. He came to me and said that we [the rest of the group] want to write songs for the next album.

“Ha!” Harley exclaims. “‘Mr Soft’ had been a hit off the Psychomodo album, Psychomodo was top-five, we were selling out dates all over Europe, we were doing rather well with me in charge, I thought, so what are they worried about? We’ve all come out of obscurity into this.

“So I said, ‘No, I’m not ready. I’ve already written the new album, I’ve already finished it’ – even though I hadn’t. ‘No, I don’t want to sing your songs. I’ve got a million ideas of my own, my head’s full of creative thinking.’ Reame-James told me, ‘We can write songs, too’ and I said, ‘Well, go on, go and do that, then’.

“It was a mutiny, and he took with him two lovely young fellas [violinist JeanPaul Crocker and bassist Paul Jeffreys; much later, in December ’88, Jeffreys was tragically killed in the Lockerbie aircraft disaster].”

Despite his protestations of innocence, at the time of the bust-up it was widely reported that Harley sent Reame-James packing with the words: “I could stand up with four cardboard cut-outs and still be a star.”

“Yeah I probably did,” Harley chuckles. “Sounds like me, doesn’t it? Of its time, not a bad quote. No, they ruined it for me. They dropped me in the mire, left me in the lurch without a band. Stuart [Elliott, drummer] stayed with me, but the three of them walked out to go their own way and prove their own point. But they screwed me. I was already booked to headline the Reading Festival in August and I hadn’t got a band.”

Initially, Harley’s career was robbed of momentum. Mr Soft, released in July ’74, got to No.8. But the follow-up single, Big, Big Deal, didn’t chart at all. So Steve focused his anger and wrote a song about the Cockney Rebel estrangement, Make Me Smile (Come Up And See Me). Released in February ’75, it gave him his one and only No.1 hit single in the UK.

“Yeah, one good thing came out of it [the split] – Make Me Smile. It’s a good song. It’s my pension – it’s the truth, and I don’t mind owning up these days,” Harley proclaims. “So Make Me Smile came out of it, and it isn’t the sweet pop song everyone thinks it is, it’s quite dark actually. But it’s phenomenal. I wish I had ten of them. It is huge over most of the world. I hear it everywhere I go, all over Europe… It was being played in a restaurant in Menorca I visited with the family a few months ago and it blasted out. I said, let’s hit the road, I don’t want to sit here and hear that!” he laughs.

Harley assembled a new Cockney Rebel, retaining drummer Elliott and bringing in guitarist Jim Cregan (ex-Family, and responsible for that deceptively complex signature solo on Make Me Smile), Duncan Mackay (keyboards) and George Ford (bass). The prolific recording output continued: an album called The Best Years Of Our Lives was released in March ’75 and reached No.4; the single from it, Mr Raffles (Man It Was Mean) peaked at No.13.

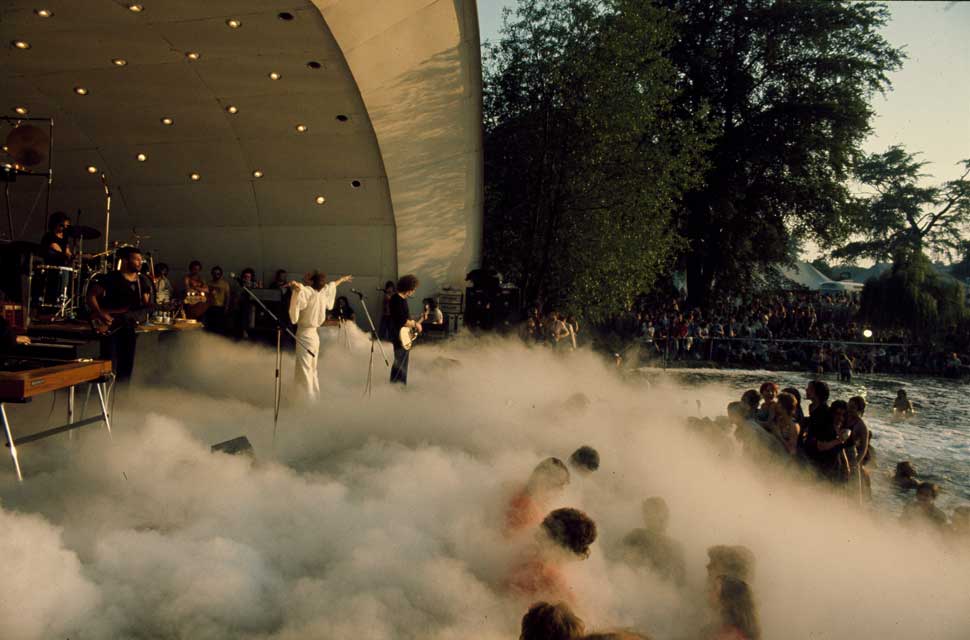

When Harley and his new Cockney Rebel played in the open air at Crystal Palace Bowl in south-east London in June ’75, the singer – in bare-faced Jesus Christ pose – planned to walk on water in the lake in front of the stage. It nearly paid off until the fans decided to cool off – it was a blazing hot summer’s day – and take a dip in the lake, and discovered a crafty ramp just beneath the water’s surface.

“We had a fibreglass board, like a diving board, a springboard, that had been built out of the stage on blocks into the water. It was three inches below the surface and I was going to walk on the water, ha-ha! It was just like what the NME said I thought I could do,” Harley chortles.

Guitarist Cregan left to join (and write songs for) Rod Stewart’s band, but the Harley albums kept coming: Timeless Flight (February ’76), Love’s A Prima Donna (October ’76). In between Steve had another Top 10 single, with a jaunty reinterpretation of The Beatles’ Here Comes The Sun. A live album, Face To Face, was released in June ’77 – and promptly disappeared amid the onslaught of punk rock.

“My fans weren’t interested in punk,” Harley says with a shrug. “The Sex Pistols… I was five years too old to dig that, why should I pretend to dig it? It wasn’t aimed at me. I wasn’t a punk, I wasn’t going to jump on any bandwagon, I wasn’t even going to pretend that it had any merit to it. It was a social phenomenon, it wasn’t music. It didn’t take the place of music, did it? So… it came and it went. It allowed a lot of people with exceedingly limited ability to get on the telly. I couldn’t really care less, to be honest.”

But, perhaps spurred on by such a brazen attitude, a certain Malcolm McLaren stepped into the ring and delivered a blow that landed firmly below the belt. When The Sex Pistols were dropped by EMI, the band’s svengali announced that it was all Steve Harley’s fault, because he’d sniffily told the suits at the top that he didn’t want Johnny Rotten and his snotty friends on ‘his’ label.

“I had no axe to grind except that Malcolm McLaren tried to use me to his and his group’s advantage, which I found rather distasteful,” Harley complains. “When EMI sacked The Sex Pistols, McLaren commented that it was because I wanted them off the label. As if I had any influence; my sales were already down, and I don’t think I carried a lot of clout at EMI. McLaren knew perfectly well he was making it up, he was making me look like the bad guy in the middle of it all, and I had nothing to do with it. EMI could have put him straight, but he made it up because he was a bigger self-publicist than I was, for Chrissakes!”

Harley was getting dragged down, and it began to get worse. The singer acquired an American manager, Ed Leffler (who had been The Beatles’ tour manager in the 60s, and would later go on to direct the career of Van Halen before his untimely death from thyroid cancer in ’93). Leffler persuaded Harley to leave Britain and move to the States.

“Yeah… yeah… that was one of my mistakes,” Harley confesses. “I didn’t do much work for about a year and a half. I was living in Coldwater Canyon and basically getting up late, drinking a lot of champagne, having brunch, staying up all night partying, doing drugs. I really regret going to live in California, it was the start of a serious decline in my popularity, and in my creativity.”

One day in the US, Harley decided to ring his accountant back in England: “I asked him to transfer some funds, and he said to me that the pot was empty. I remember my mouth drying. I’ve kept a very, very close eye on my finances since that day. So I packed up and came home. I did a good album, Hobo With A Grin, there… that one and The Candidate were the last two for EMI. They were [July] seventy-eight and [September] seventy-nine.”

Then came the 1980s – which Harley sometimes calls “a lost decade”. He sighs: “I fell hopelessly in love. In eighty-one I was married, in eighty-two my son was born. I think I was tired of rock’n’roll, my popularity was waning, and it wasn’t until eighty-nine that I toured again. But I was active throughout the eighties and I did the Phantom Of The Opera stuff for about nine months [gaining a hit single with Sarah Brightman in December ’85; but Harley was beaten to the lead in the London stage show by Michael Crawford]. I did a single called I Can’t Even Touch You with Midge Ure, put it out on Chrysalis, I did a Jon Anderson charity record…”

Although all this was a far cry from the heights of Cockney Rebel, Harley remained philosophical: “I have to say that I enjoyed having children and chilling out, and I did begin to have a good income again. I got my hands back on the purse strings through the eighties; I wasn’t broke at all, even though my accountant said I was. It was just lying around in other places, and there was money owed that wasn’t getting to me. I unchained all those locks and I started stamping my foot and sorting people out.

“I actually had a very good life all through the eighties,” he adds. “I’ve always lived in lovely houses, and to this day I don’t owe a penny to anyone in the world. But it was in eighty-eight that this man [Steve Mather] came to me through a mutual friend. He was in showbusiness, but he was a fan of mine. Mather had an agency for actors in Shaftesbury Avenue. We met for lunch, and he looked me in the eye and asked me: ‘Would you like to go back on the road?’

“I said: ‘Why are you asking? You’re an agent for luvvies.’

“‘I’ll do it,’ he said. ‘I’ll get you out on the road.’ “I said: ‘But I don’t think I’ve got an audience; no one will want to see me. I don’t know who I am any more. How would I do a show? What would it look like? What would I wear?’ Stupid things like that, almost like nervous-breakdown details that are pathetic and pitiful… neurotic. I was neurotic about it in private.

“But I called him back and said: ‘What’s on your mind?’ And six months later I was in Germany doing three weeks. I came back and started Britain, did a week or five nights at The Venue in Victoria, and I’ve carried on playing ever since. Mather got me out there, God bless him, he kind of twisted my arm. He didn’t earn a lot from it, and he eventually went off to be a barrister specialising in contract law. But I can never, ever forget him.”

These days Harley has a regular radio show slot every Tuesday evening on Radio Two’s Sounds Of The Seventies. But touring remains his passion, whether it’s with the aforementioned electro-acoustic combo or with the “full rock band” (Cockney Rebel). And he’s doing rather well out it: “Most of the biggest live performers in the world don’t sell records. But touring, it makes fortunes. Mine is a very, very handsome annual income, but strictly between me and the taxman and my accountant – my new accountant, of course,” he grins.

“Record-wise, I haven’t done much,” Harley continues. “The Yes You Can album was in ninety-three, and in ninety-six or ninety-seven was Poetic Justice – a lovely record, I think. Those are the two nineties albums, apart from the new live one, Anytime. That came out well. I sound very grown-up on it. I also notched a minor hit single with A Friend For Life two or three years back.” The latter, later recorded by Rod Stewart, is a bang-on return to form – for the married men among you, it’s a bona fide tearjerker if you listen to the lyrics too closely.

Harley says there are people around him these days who want him to be more ambitious, “but what they don’t know is that in a sense I am. But I have an awful fear of rejection. I’m sort of better off not releasing a record than having it slagged by people. I’ve got a total horror of rejection, and I don’t know why that is. I guess it goes back to Little Steve in that hospital and that little cupboard by the bed.”

Harley doesn’t plan to wind things down any time soon: “I say to people, you can wheel me out there when I’m seventy-five, just please God give me a voice. All I want is a voice and some people who like to listen to it. You don’t retire from this – well, at least I don’t. Mick [Jagger] will have to retire from running about like a twenty-year-old. He’s got to, because it’s starting to look somewhat ridiculous. I’ve never done that. I’m James Taylor, I’m Carole King – I just sit and play and sing. It’s a job for life if you do it properly, and if you show humility and respect. All I want,” he repeats, “is an audience.”

Horse racing is another of his fervent interests, and he is part-owner of several nags: “I had a bad Cheltenham… until the end,” he smiles. “There is a God. I was nearly two thousand pounds down over the three days, and in the last two races I had rather large each-way bets at eight-to-one and six-to-one, and they both won. Got nearly all my money back. I was about eighty quid down after being two grand down.”

In a statement that sums up his topsy-turvy career, Harley adds: “You’ve got to be fearless to get the wheels back on the bike. You cannot quit. I don’t gamble, I don’t go on the roulette table; I don’t back horses I haven’t studied. When I back a horse I believe it should win the race. That’s not gambling, that’s a bet.”

There’s Steve Harley for you. Still a Rebel, and still playing the game and winning. Or at least breaking even.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 71, published in October 2004. Steve Harley died in March 2024.