On June 7, 2005, Dave Ling travelled to the Icelandic capital of Reykjavík to witness Iron Maiden’s show at the 15,000-capacity arena Egilshöll. There, he caught up with founding member Steve Harris and looked back on the bassist’s legendary career…

Much as any opportunity to witness an Iron Maiden concert is savoured, I’d been dreading this particular diary date. Why oh why wasn’t I despatched to meet Steve Harris a year ago, after my own team, Crystal Palace, had stuffed his beloved Hammers in the Division One play-off final?

Now, with Palace relegated back to the Coca-Cola League and West Ham fluking their way back into the Premiership, spies in the Maiden camp say Harris is looking forward to greeting your correspondent when we rendezvous in Reykjavik. In the event our banter is good spirited, despite my prediction that the roles will be reversed next season.

Steve is passionate about everything in his world, particularly Iron Maiden and football. He had a trial for West Ham at age 14, but it was his second love, music, that hooked him proper – though he still likes to talk like a pundit.

“A lot of footballers give up when they’re supposedly at the top,” said Steve in 1998. “If it’s a case of them not loving the game any more, that’s fine, but I don’t understand when ego makes them stop. Once you’ve reached your career peak where’s the shame in dropping down a division if you still love the game?

“Musically, I’m sharper than I’ve ever been. I really wouldn’t mind playing [smaller venues like] Guildford Civic Hall as long as people come to watch. Okay, if nobody turned up then you’d have to reconsider, but I’m as happy playing Guildford as I am Madison Square Garden. If the fans are hungry, I’m hungry too.”

Harris doesn’t still love the game – both games – he worships them. He’s also pretty damn good at them. Seven years since that interview, six since the departure of vocalist Blaze Bayley and the triumphant return of Dickinson and Smith, Maiden are flying Champions league fixtures have replaced relegation dogfights. Shades must be donned to examine Iron Maiden’s gleaming silverware cabinet.

Dream Theater, Machine Head, Soulfly, Killswitch Engage, Cradle Of Filth, Mastodon, Funeral For A Friend, Shadows Fall, In Flames, Arch Enemy, Soilwork, The Haunted and Trivium, have all cited Maiden as a key influence. Harris and Dickinson are the Moore and Hurst of metal, and Maiden the equivalent of the 1966 World Cup-winning England team.

All 53,000 tickets for the band’s Gothenburg date on the Eddie Rips Up Europe stadium and festival tour were snapped up in less than three hours. It’s a great time to be in Iron Maiden, isn’t that right?

“It’s always a great time to be in Iron Maiden,” smiles Harris, not even that smugly. Although he acknowledges a strong competitive streak, conceit is not part of the Harris’ makeup. Those who have known him from the outset say stardom hasn’t changed him at all. Away from the spotlight Steve is a retiring, sensitive bloke.

“I’ve never been too comfortable making small talk,” he says. “That’s why it’s great to have someone like Nicko [McBrain, drummer] around. I find that part of the business pretty difficult. People expect me to be aggressive and loud and I’m not. They also seem to think I’m a lot shorter in person.”

Steve was born in the back room of his grandmother’s house in Leytonstone, a working class area of East London, on March 12 1956. He was the eldest of four children and the family’s only boy. “My father was a truck driver and we led a fairly simple life,” he says. “We weren’t exactly poverty-stricken, but we weren’t well off either. We were definitely a happy family.”

The Harris household rang with music, his sisters indoctrinating him to the sound of The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel and Tamla Motown. The phenomenon continues, with Steve’s offspring already playing in bands of their own. Aged 17, Harris bought a Telecaster copy bass for the, then, fairly extravagant sum of £40. By this stage he had given up his aspirations to become a professional footballer, despite having signed schoolboy forms with West Ham.

“I trained with them for about nine months and probably had a realistic chance to have gone down that route,” he says. “But at that age other things come into play. You start getting interested in girls and beer and it was impossible to do both. I became involved in music quite late, but once I did, I knew what I wanted to do.”

The young Harris became a huge fan of Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Judas Priest, the Scorpions, Jethro Tull, The Who, Wishbone Ash, King Crimson, Todd Rundgren and early Genesis and he’d go and see any of them live any chance he got. UFO bassist Pete Way was an early Harris idol, and it’s speculated that Steve, who met Way as Maiden were starting out, was so impressed by his hero’s affable humility that he chose to copy it.

“I don’t like it when anyone tries to make you feel different,” he says. “Because you’re not, and I certainly don’t want to be. I’m not complaining about the whole stardom thing, that’s just the way it is.”

Steve initially considered taking up the drums but didn’t have a room in which to store or play a kit, so he chose the bass and played along to records like Free’s All Right Now and Deep Purple’s evergreen Smoke On The Water. The notion of taking lessons was a complete non-starter, which ultimately benefitted Harris’ unique style.

“Steve taught himself in such a way that nobody can really copy it,” reckons Maiden guitarist Janick Gers. “People say it’s like a lead guitar, but it’s not. It gives the band a basis and it moves around quite a lot, but it’s the tone that he has. Steve has a way of hearing things and a tone that isn’t normally associated with a bass, it’s more like a rhythm guitar.”

A certain level of musical proficiency established, and with a day-job as an architectural draughtsman, Harris co-founded a band called Influence who quickly became Gypsy’s Kiss (the Cockney rhyming slang for taking a piss). They lasted a half dozen shows, before Harris threw in his lot with a boogie-rock outfit called Smiler. Despite their Fleetwood Mac style, Steve persuaded them to play one of his earliest songs, Innocent Exile (it later surfaced as Killers).

They were less impressed by Burning Ambition, another Harris composition that became the flipside of Maiden’s debut 45, Running Free. Like the song, Steve had a firm set of career goals, Smiler apparently did not. “They thought my songs had too many time changes.”

His boundless stage exuberance frowned upon, Steve quit Smiler and on Christmas Day 1975 set about forming his own band, taking the name Iron Maiden from a torture device he’d seen in a movie version of The Man In The Iron Mask.

As well as forming the band, it’s Steve’s love of Boys’ Own style adventure that has so spectacularly coloured the group’s repertoire. In the early days, Steve wrote pretty much all the material. But as new, more capable musicians came on board Steve relaxed his grip on the songwriting, but he never gave up his love for translating ambitious narrative into grandly- themed audio drama. To Tame A Land (from Piece Of Mind), Rime Of The Ancient Mariner (Powerslave), the title track of Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, Mother Russia (No Prayer For The Dying), The Sign Of The Cross (The X Factor) are just the tip of the literary iceberg.

Since forming the band, musicians and singers have come and gone, but Harris has always maintained his big picture vision. Three decades in, Sergeant Major Harris still calls the shots in Iron Maiden.

“Harry is my boss,” McBrain says when asked about the group’s chain of command. “Rod [Smallwood] is my manager, and he’s incredible at his job but sometimes he’s there to play good cop/bad cop. He informs us all of decisions that Steve has made. That’s the nature of Maiden. We’ve succeeded because everybody knows their job, and sticks to it.”

It’s a game plan that’s paid-off handsomely. Many felt Harris had completely lost his marbles when he chose to dispose of a frontman as charismatic as Paul Di’Anno. But Di’Anno was in self-destruct mode and his performances sucked. Nobody short-changes the fans for long on Harris’ watch.

It’s well documented that Steve had to talk Smallwood – who felt that Maiden had been “stitched-up” by rival band Samson – around to the idea of poaching the group’s singer Bruce Bruce (aka Dickinson) as a replacement for Di’Anno. But how astute did that decision turn out to be? It was also hard to give marching orders to Clive Burr, whose playing quality fluctuated according to his post-gig habits. But in 1983 Maiden were at a crucial point in their career and couldn’t afford slip-ups, so Burr went. The wayward drummer’s replacement, Nicko McBrain, has been with the group for more than 20 years, another tick in Steve’s ‘vindicated’ box.

As well as whip cracking, Steve is also capable of accepting good counsel. The band wanted his chosen frontman, Blaze Bayley, to go and a reunion with Dickinson initiated. Having hand-picked Bayley and enjoyed a comparatively stress-free collaboration with the ex-Wolfsbane singer, it was a difficult pill for Steve to swallow. But he choked it down. Despite being a tough boss, he remained loyal to Bayley and, even with Dickinson back in the fold, flatly refused to discuss the reasons for letting Bayley go. “I appreciate it makes your job a lot harder but if Blaze hasn’t spoken about what happened then neither will I,” he said at the time.

After the retirement of producer Martin Birch, Steve had seized the role of producing Iron Maiden’s records. This became a sticking point with Dickinson who heard a set of Dream Theater demos and realised they sounded better than an officially sanctioned Maiden recording. Sure enough, when Bruce agreed to rejoin the group in 1999, Kevin Shirley of Aerosmith/Dream Theater/Black Crowes fame was installed behind the console (with Steve agreeing to accept a role as ‘co-producer’).

Janick Gers is one of the first to big up Steve’s fairness. “Steve’s one of the few people that you can totally trust,” he says. “He won’t sell you down the river or badmouth you behind your back. You can confide in him and it won’t get passed around. He doesn’t bullshit and he can stand back and look at both sides of a situation. But if he’s convinced he’s right, he’ll argue with every fibre of his body and never change his mind, which I think is a great strength.”

One welcome, rare, U-turn was Steve’s acceptance of Bruce back into the group. He initially doubted the singer’s long-term commitment, believing Bruce felt an album or two with them again would re-start his solo career. “Better the devil you know,” is how Harris described it.

“I’m as pleased [with Bruce] as I can possibly be at this time,” said a wary Steve after a sell-out gig in New York’s Madison Square Garden in 2000. “In six months it could all go pear-shaped.”

Five years later and it still hasn’t.

“There was a part of me that wondered, ‘How long is this gonna last?’,” confirms Harris in Reykjavík. “After all the fuss [of the reunion] had died down, how long would Bruce want to be around? I was unsure. But I don’t feel like that any more.”

We find Maiden in top form. They’re touring Europe and America with a live set culled from their first four albums, and next year they’ll record their third post-reunion studio disc.

“Nothing about the next album is certain yet,” says Steve. “I put down ideas on tape all the time, but I never work them up till a lot nearer the time.”

Steve says he was “very happy with the response” to the last record, despite some duff reviews.

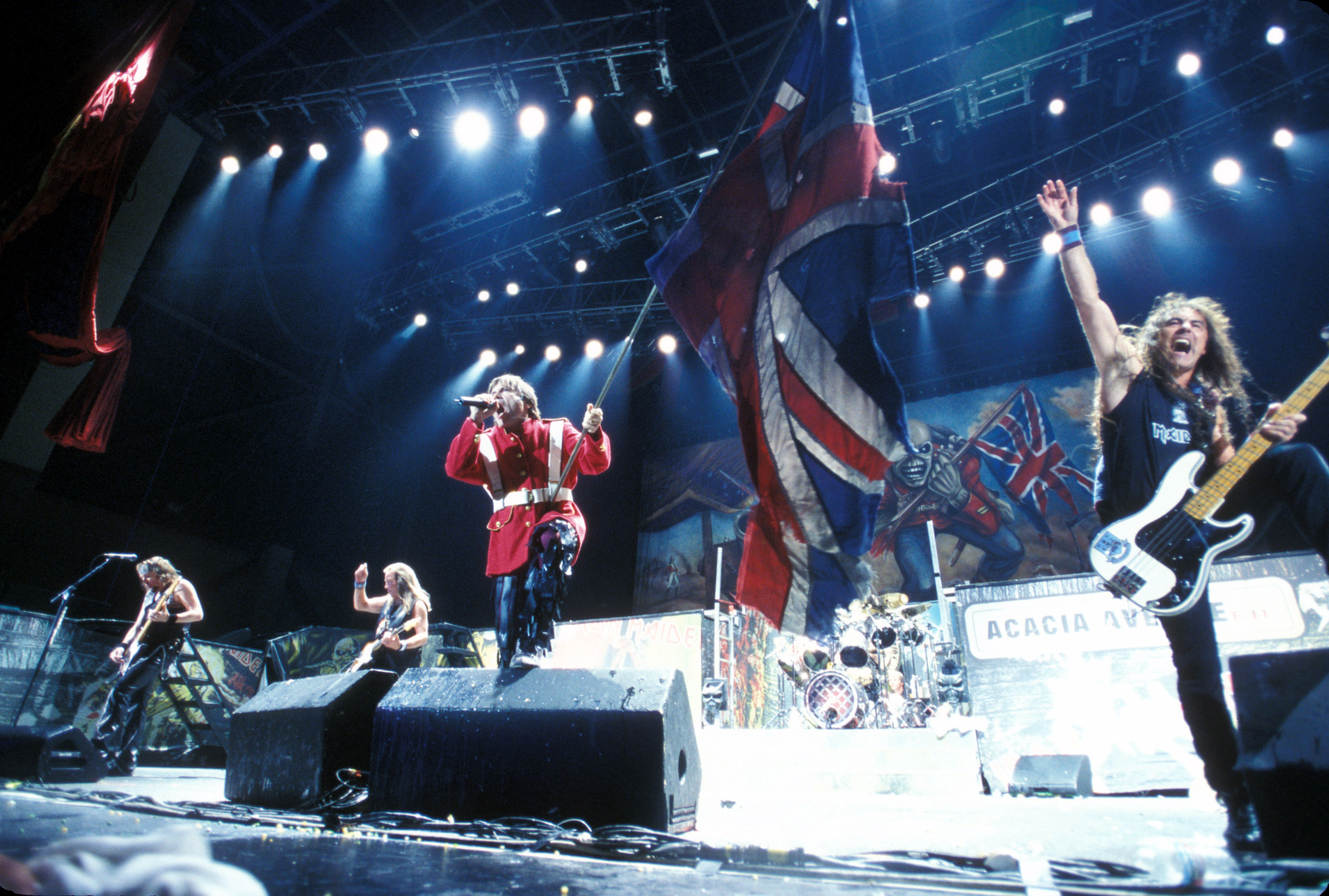

“I’ve never let those bother me,” he grins. “The material was strong, and some fans said the tour was the best we’ve ever done. It’s difficult for me to comment, but it was very theatrical. Bruce hamming it up in all his different outfits was great. Editing the live DVD [Death On The Road, filmed in Dortmund] gave me goosebumps.”

Regarded by some as a living anachronism (“I’ll cut my hair when I’m fed up with it and not before”), Harris is aware the band are entering the twilight of their career. “From now on, every gig is sacred,” he says. If the set of the Eddie Rips Up Europe tour is a belated bid to place Iron Maiden in the pantheon of all-time hard rock greats, then it’s successful.

“A few years ago it was all computers, but live rock music is finally coming back. All around the world we’ve had no problem pulling in new young fans,” says Steve. “But it’s been a bit more difficult in the UK. That seems to be changing now. It’s very exciting.”

This feature originally appeared in Metal Hammer Presents: Iron Maiden – 30 Years Of Metal Mayhem in 2005.

For more Maiden and their legendary World Slavery Tour, then click on the link below.

Scream For Me: Down The Front On Iron Maiden's World Slavery Tour