Steve Howe: the ultimate interview

Steve Howe was the guitarist with proto-psychedelic Brit-rockers Tomorrow. Then he joined Yes and embarked on a hugely successful career as a member of prog royalty

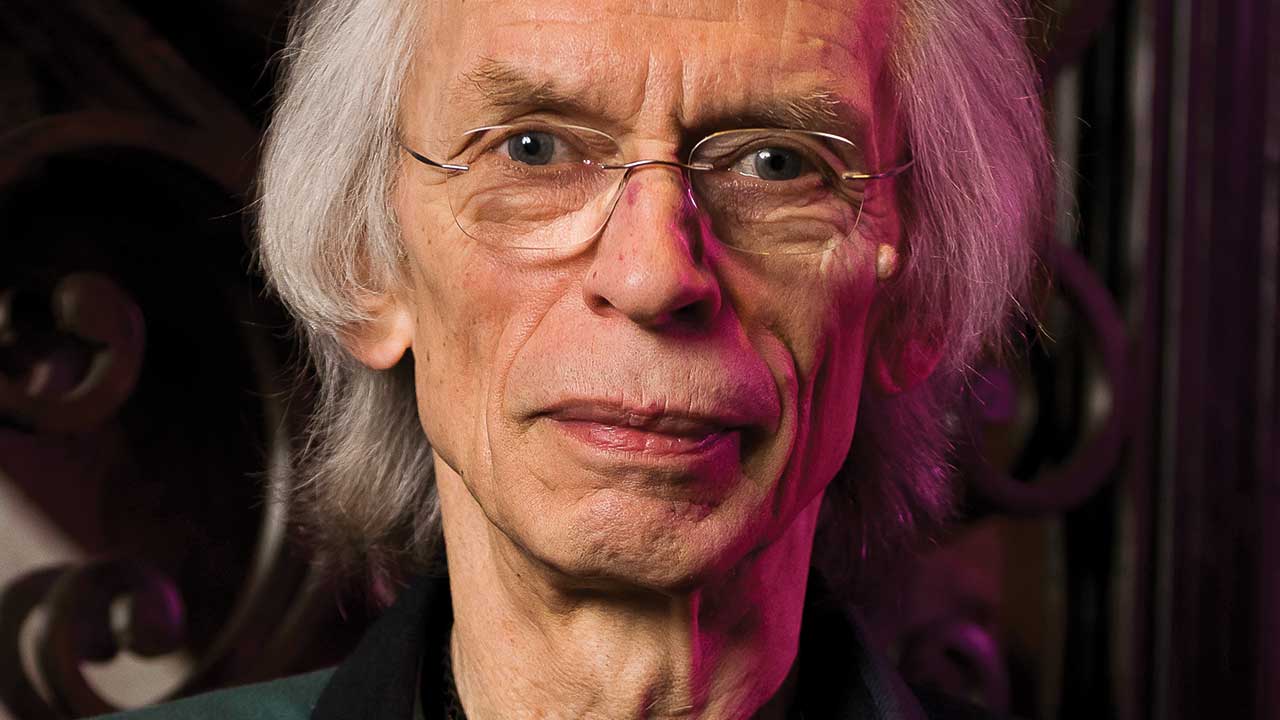

Steve Howe is one of those people to whom photographs no longer do justice. Approaching his seventy-third birthday, the polite, engaging English gentleman Classic Rock meets today in the restaurant of a London hotel is far removed from the cadaverous, wispy-haired figure of his publicity shots.

He’s still scarecrow-thin and ghost-grey-skinned, but alert and warm in person. A lifetime of being one of the (many) leading lights in Yes, a group whose music never knowingly stooped for the merely catchy when opulent melodrama and maze-like intricacies were always within reach, has left Howe sitting atop the mountain, in terms of reputation, fame and guitar-artistry. Although it’s the decades of first vegetarianism, then devotion to macrobiotics and long-form transcendental meditation, you feel, that has given him his ageless aura.

Don’t mistake any of this for some sort of old-school hippie-flakery, though. Howe was born in the post-war rubble of Holloway, norf-London, the youngest of four siblings. His parents, he says, were, “very strict”. But he always knew he “was going to find some other way of getting through my life, that didn’t involve a regular job”.

He began playing guitar at 12, playing in school bands, joined his semi-pro group, The Syndicats at 17, released his first single, a cover of Chuck Berry’s Maybellene, at 18, and joined The In-Crowd, who had just had a minor chart hit with a version of Otis Redding’s That’s How Strong My Love Is, just a few months later.

When The In-Crowd transmogrified into Tomorrow – now recalled as one of the proto-psychedelic Brit-rockers of the acid-rained Summer of Love – he glimpsed the future. “I was ready to really show the world, to improvise.”

He has continued to demonstrate that ability ever since, mainly through the prism of Yes, but also, unexpectedly at the time, via the power balladry of Asia, GTR, ABWH and any number of solo albums, one-off collaborations and attendant musical wizardry.

Later this year he was due to tour again with Yes, revisiting their 1974 album Relayer, although only Howe and drummer Alan White from the current line-up played on it. Coronavirus put paid to those plans, and the dates will be played in 2021. He also has solo shows planned for the autumn, a new book, All My Yesterdays is out now, and a solo album, titled Love Is, “fifty-fifty instrumental and songs”, is due in July.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Tomorrow, which you formed with singer Keith West, who was about to become famous in his own right as singer of Grocer Jack (Excerpt From A Teenage Opera), came along just when albums had become more important than singles. Experimentation, expanding the idea of pop music. It wasn’t just Tomorrow, it was Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, Jimi Hendrix, all led by The Beatles. How self-conscious of that were you at the time?

Yes, with Tomorrow we were in the centre of it all, and we loved that. We were just having a great time. The UFO club, concerts at the Alexandra Palace, or at Earls Court, all the psychedelic things, we were part of it all. And the world was our oyster. We were most probably living in Chelsea, all living it up, on seventy-five quid a week.

Yet it all fell apart after one, albeit mind-blowing, album. Why?

We were doing very well, but unfortunately none of us knew how to hold a band together. So the record was late, it came out in 1968. So it was only really the single My White Bicycle that people can associate correctly with Tomorrow. But when we played on stage, we played with such conviction and speed and excitement. We had a kind of edgy craziness to it. And this allowed more improvisation. So a song would start, and then, for example, we’d go off on some imaginative journey. We weren’t the only band doing it. But we did it in a particular way that people liked.

Did you know those other guys – Floyd, Hendrix and so on? Did you see them as rivals in any way?

Yeah. We saw them as equals, sometimes. But we were all very egotistical, as far as “We are good. We’re going to blow this band off stage.” But when you’re young and naïve you’ve got this bullshit factor that helps you through a lot. But as I said, we didn’t understand how to hold a band together. So I then had a couple of leaner years, sixty-eight to sixty-nine, in a group called Bodast.

An even more short-lived and far less influential quartet that had the misfortune to be signed to the Tetragrammaton label, which went out of business just before the scheduled release date for the Bodast album. How would you nutshell that story?

Bodast was a struggling, kind of desperate band, really. But what we were honouring was that we wanted to do all our music, and to hell with the world, you know what I mean? And we paid the price. The album was good. But that band just struggled. Everything was a struggle. We got let down.

How much did LSD have to do with the kind of music you were making at this point?

I saw other people going a bit in there with that, and I thought: “Well, I’ve got to try this stuff.” But I always minimised what I took. And I thought: “Well, that was enough for me!” Thank God I didn’t take any more of the stuff. It influenced my life for many years, yeah. But I was young enough to absorb the transition that it maybe took me through. The heightened awareness of nature was the most beautiful thing about it. I guess in a way the hippies were the original eco-friendly guys.

Back to the garden?

We were in the garden. We loved animals. When you’re seeing creatures that you share the world with, under those influences, it’s quite mesmerising. So we had a lot of fun. We giggled around a lot. We listened to music, and thought: “Oh, this is wonderful.” The whole thing was like an event, a constant event. By the time I joined Yes [in 1970], I think the influence was still there.

Had original Yes guitarist Peter Banks left the band by then?

No, not really. But they were trying to cover their bases and then telling him. So basically, without much ado, that was when it all clicked in with me. Because when I got there it was fairly easy to see that this was great, and hey, I wanted to join. And they saw something in me, and said: “We’ll offer you the gig. Twenty-five quid a gig.”

So I thought: “I can just about live on that.” I had the belief that the people I was joining with were very talented, very individual, and I think that’s what I’d been looking for, individual values in people.

Were you already on a mission, to broaden the musical scope?

Yeah, I think that’s a big point. We didn’t have a hit we had to play every night yet. It was really ground upwards. To me it felt like a new band. I think they sensed that a little bit, too, that this was going to be something they’d really want to commit to, because of the quality that we’d created together.

And that was, not least of all, because of our writing and rehearsing in Devon, where we kind of got our heads together, in songs like I’ve Seen All Good People and Perpetual Change and Yours Is No Disgrace. These were not small, dismissible works. Because underneath it, none of us wanted to stand still, play blues riffs or do anything that most other bands were doing. And the fact that [Yes vocalist] Jon Anderson and I became a strong songwriting team didn’t hurt the band at all.

Why did you and Jon become the real songwriting force, not, say, you and Chris?

Chris was a great writer, but you really didn’t sense he wrote a great deal. So his output was lower than Jon’s and mine. And Rick [Wakeman, keyboards] didn’t write for Yes, really. Bill Bruford had a weird way of writing, because he’d write ideas on the piano, although he was a drummer.

So the way you could write in Yes wasn’t that you went home, and you came back with some written music with words on it. Not at all. You just could sit in a room and go: “I got this, I got this, put that over there, and let’s just go to that.” And then somebody at the same time said: “No, we need a riff here.” The band would actually invent music, a lot of it, through that method, where it was purely spontaneous in the room.

Of course, you had to force your music across, otherwise somebody else would change it, and it wouldn’t be what you wanted. It was a creative interplay.

What Yes did was take simplistic things and complicate them a little bit, for our amusement.

Would you and Jon work on your own to write, and then present some ideas

Well, we did do that. But amazingly, we did most of it on the road. Jon and I would be like, “Do you want to come to my room? I’ve got this song.” And we just started collaborating in that sense, that we could both share ideas. I’ve even got cassettes where I play him stuff, and he goes, “Oh, that’s really good. Have you got anything else?” And I’d play him something else. “Oh, you got that? Let’s use that.”

I was writing melodies, didn’t care whether they were sung or played. So there were a lot of musical ideas, and Jon had some left-field ones. Sometimes it was great to have Jon’s simplicity. What Yes did was take simplistic things and complicate them a little bit, for our amusement. Sometimes we’d take the chords out and just play riffs.

So the band had songs, melodies, riffs, three-part harmonies – a technical proficiency high enough for anybody to spontaneously say: “Why don’t we do something like that?” and we would get there.

With that technical proficiency came groundbreaking albums such as Fragile, Close To The Edge, the double Tales Of Topographic Oceans, Relayer… the sort of one-track-per-side records Bob Harris would drool over on The Old Grey Whistle Test, and their critics still look down on as the kind of thing that public schoolboys masturbated to.

Yes, meanwhile, became one of the biggest, bands on the planet, achieving Led Zeppelin-levels of success. And with that came that deadly scourge of all successful groups: ego. By the mid-70s Yes were becoming known as over-indulged male divas, the band’s five members split into two camps: the veggie, meditating life-affirmers (leaders: Howe and Anderson) and the party-hearty rock bad boys (Wakeman and bassist Chris Squire).

As Yes became giants, people started to leave. First Bruford in 1973, then Wakeman a year later. Then Wakeman came back then left again. (And would later come back again – and leave again.) By the start of the eighties, even Anderson and Squire had gone. Why?

Unlike most bands, we… I mean, there’s five people in the band, and four of them are getting really tired, and this one guy is a bit flaky. And he goes away, and he says: “I don’t really want to be in the room.” It was like: “Oh, wow. Well, who could we get in next?”

There was no fear. And we kept wanting to kind of step up the game. So those ten years were bumpy behind the scenes. And we didn’t really want to talk about it too much. We didn’t want people to know at the time. Even people who stayed had problems. Where we had to say: “Well, look, if you don’t get this problem sorted, we’re going to have to say to you you can’t do it and carry on.”

So it was a test for people. Jon and I didn’t make it very hard for ourselves. We floated through that, in a quite cosmic, slightly spiritual, slightly out-there way. But it was harder for some other people. And they got indulgent, and sometimes we had to say, “Whoa! This is going way too far.”

That was the era though, wasn’t it? You’re feeling ill? Have a line of blow.

We wanted to avoid that. We’d all been pretty spaced-out in the sixties. We’d started to get out of that, and we banned substances like you just mentioned. Obviously, people broke those rules occasionally, and usually, were the people who’d come up against the most difficult times.

So most of us who got through it basically held it together, while somebody else was flaky. We were tolerant of it, to a degree. But also, once there was a grouping of four, with one person out of step, we were a strong force to reckon with.

Tell us about Drama, the 1980 Yes album where Anderson and Wakeman were replaced by Buggles duo Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes.

That was the big breakaway from all the traditions of Yes. Chris, Alan and I basically became a trio, with nobody else in the band. Chris said to me: “Have you heard the Buggles?” I said: “Yeah. Video Killed The Radio Star is great, isn’t it?” He says: “Yeah, but have you heard the album?”

So I put it on. And I went: “Jesus, this is good!” It’s not pop! I mean, Video is totally, but the rest of the album’s quite kind of spacey and clever, and Trevor’s singing great. And it’s lyrically very strong. I thought: “They’ll never want to leave The Buggles, that’s a hit band.”

But they came down, and we offered them a gig, and they went: “We’d love to do this.” So they delayed their second album and gave us full tilt.

Drama was a big hit in the UK, less so in the US. Good memories, though?

Trevor came through as a lyricist, and Geoff was a new kind of keyboard player, the new breed. Drama was a revelation. But nobody in America was fully clear who was in this band at the moment. Or that maybe the other guys hadn’t left yet or something. But we went out, and people went: “They’re playing Madison Square Garden, with the Drama line-up.” So we had a terrific time.

Yet at the end the group split completely. Why?

Trevor and Geoff needed to do the second Buggles album. Also, Trevor was unhappy that we were not prepared to change keys of old songs so he could sing them. Maybe that could have been fixed. But then Chris [and Alan White] went off with Jimmy Page for this XYZ thing [the ill-fated supergroup formed in the wake of the official Zeppelin split, then eventually abandoned].

Which brings us to Asia. Most musicians thank the gods for finding global success just once, but you went out and did it a second time with John Wetton, Carl Palmer and Geoff Downes.

It was disappointing that Yes couldn’t do more stuff with Trevor. But I think he felt he wasn’t supported enough, which I understand now. But by then I’d developed a good writing relationship with Geoff, and could have built a new line-up of Yes around just me and Geoff, but I was tired by then.

I’d had ten years of helping hold the band together, and I wanted a break from that. So I had a break, and had a look at what was going on in the rest of the world. Then [legendary Geffen Records A&R exec] John Kalodner called and said: “How you do fancy working with John Wetton?

Wetton was a veteran of a number of high level British rock bands, notably King Crimson, Roxy Music and UK, the latter including original Yes drummer Bill Bruford. Did you know John Wetton personally?

No, but I knew of him, of course. I knew that if he’d been in King Crimson then he was serious. We spent two days jamming, just the two of us doing all this crazy stuff. I thought that’s where we were going. Then John said: “I’d like the band to be more song-based.” I said: “Great. I’m happy with that.”

That’s when we came up with things like One Step Closer and Without You. Then John said: “What I’d really like to do is get a drummer like Carl Palmer.” I thought that sounded amazing. ELP drummer, Yes guitarist, King Crimson bassist/vocalist…

So Carl came in and he was impressive! You don’t need to hear him, you just have to watch him [laughs]. Then I said: “We need a keyboard player.” They said: “Just be a trio.” I said: “No, no, no, you’ve got to get this Geoff Downes guy in!”

So I brought Geoff in to play with Asia too, because I liked working with a guy who was at the edge of technology too, because I was doing that with my guitars and effects, and I was trying to have the best sounds. We also had a strange limbo where we tried out other writers and singers. Roy Wood was one, who was a lovely, lovely guy but not really the right fit for us.

Wasn’t another one Trevor Rabin, who ironically didn’t get the gig but later replaced you in the re-formed Yes?

That’s not a very public story. We were looking for someone that could add to the writing, but again the chemistry just wasn’t there. Another one was a guy called Robert Fleischman, who had sung with Journey briefly. In the end we stuck with the four of us and everything just clicked from there. The whole machinery behind Yes jumped ship and came with us, management, crew, etcetera.

For all Asia’s obvious musical prowess, the band’s big hit, Heat Of The Moment, was the epitome of slick-sounding, early-eighties power-balladry. More Journey, in fact, than Yes. How did that happen?

Well, the production was a bit Journey-esque. That was down to Mike Stone, who’d co-produced Escape, which was a huge album for Journey. But Heat Of The Moment was the last song we recorded for the Asia album. By then we’d already done stuff like Time Again and Wildest Dreams, which were very progressive. There was also this sweetness in Time Will Tell. But as soon as I stacked up the guitar and John started singing, we knew we had something special in Heat Of The Moment.

A huge hit single, it helped send Asia to No.1 in America. What was that like?

It was wonderful, of course. It felt like vindication after the way Yes had fallen apart, really. But I’d already experienced highs like headlining sold-out arena tours of the States in Yes. As had Carl. But for John it was something else, I think. The pressure was really on, and I think the sheer scale of the success had an effect on him that made him quite introverted in a way. Very cut off.

I don’t like the stories you hear about me and John Wetton falling out. It was never that simple.

Your personal relationship with John also suffered, didn’t it?

Well, I don’t like the stories you hear about us falling out. It was never that simple. The whole thing just got out of control. None of us were happy with the mix of the second album, Alpha.

The tour was crazy – too many champagne breakfasts, you might say. That’s when I started driving myself to shows rather than fly with the band. But we ended up pulling the final dates. It was a mess. People started forgetting parts, or running orders, or whether it was the single version or the album version we were playing.

That’s when we spoke to John. He said: “It’s not all me.” Yes, but if you’re singing and playing and you go somewhere we don’t know, we’re going to have problems. At that point it started to fizzle out.

While the end of Asia was messy, with Howe being fired from the group, Yes were about to embark on their own new adventure with the 90125 album and the revamped line-up starring Howe’s replacement on guitar, Asia reject Trevor Rabin.

Howe laughs about it now, and acknowledges the astonishing success the single Owner Of A Lonely Heart brought the group. But can’t resist the teeniest dig when he says he thought the video for Owner “looked like Duran Duran”.

Musically, he says, “it was like a whole new band. The bass and drums were the most radically different. I thought there was even a slight Asia aspect to it.”

Not to be outdone, Howe formed a surprisingly fruitful partnership with former Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett in the short-lived but amazingly successful outfit GTR, whose self-titled only album hit the US Top 10 and gave him another chart single with When The Heart Rules The Mind.

Behind the scenes, though, there were tales of the pair not getting along, with rumours that Hackett would not stay on the same floor of a hotel as Howe and the rest of the band. Too damn noisy, apparently.

Howe then found himself back on the Yes trail. First with the cumbersomely named but musically wondrous Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe (ABWH), which bled into an unctuous collaboration between that line-up of Yes and the 90125 guys with the almost ironically titled Union in 1991.

Later came his one-off reunions with Asia, a further expulsion from Yes for one album, to where Howe is now, de facto leader of all he surveys.

The Union album was interesting. The tour less so. Too many cooks?

It was immensely complicated even before we’d put our tracks with their tracks. There was all this signing off on things to be done, and everybody had to agree to this and that and blah, blah, blah. But that whole album became a hodgepodge. I did a lot of things that didn’t end up on that album.

Then people wanted to be on stage all of the time. The best were in the UK where there weren’t several people playing the same things at the same time and there was far less spotlight-hogging. The hardest was the first leg in America, where I wasn’t ready for what Trevor Rabin was gonna do on Yours Is No Disgrace.

Then after a few nights everybody was going to him saying: “Steve’s unhappy.” Because I was. It was a little bit more heavy metal than I could put up with. This was Yes, after all. By the time we got to Japan at the end of the tour it was becoming a real struggle.

Jon Anderson finally bowed out after the 2001 album Magnification, amid much public recrimination. How is the love-hate relationship between the two of you now?

I’m not going to tell you a lot. But in the seventies Jon and I were a great team. After that, in the eighties, that role got diminished. Then we came together again for ABWH, and the Yes continuation right up to the final split in 2004. That’s an awful lot of time. Stimulus, agreement and likemindedness most definitely fluctuated continually. But it was never impossible to work together. But it wasn’t as dream-like as the seventies.

Is that door still firmly closed?

Jon and I get on really well now. We have the history and the friendship. But it’s probably better that we don’t attempt to work all the time together – because of this and that. But nobody knows what the future holds.

Time waits for no one, though. Chris Squire died in 2015, John Wetton in 2017. How did those losses make you feel?

Chris was having some difficulties for some time. We had to cancel some shows once for him to have some [heart] surgery. The year before Chris passed was really touch and go. Chris spoke to me on the phone two days before he passed saying: “You know, I think I’m going to be alright.”

But he had a relapse and there was no coming back. We were really messed up by that, losing somebody you love. Whereas when John went it was slightly more of a shock. It was similar in some respects, in that John had some problems. But he seemed to be fine. I mean I knew he was unwell but it was hard to believe that John had passed away. More sort of catastrophic.

You also suffered a dreadful family loss when your son Virgil died in 2017.

He was forty-one and had a heart attack of some kind and we don’t really know any more. It’s our biggest tragedy of our personal lives in our family to lose Virgil, since we loved him so much. We’d just formed a musical partnership as well. We’d just recorded Nexus, and we brought it out even though it was a couple of months after he passed away.

He was really proud of the record. It was really his music and my collaboration. So it’s a record that has sadness about it. If he hadn’t passed away we would have immersed ourselves in it and enjoyed it so much more. But then there was Greg Lake too, who I didn’t know that well but who didn’t have the longevity that he should have.

Then Keith Emerson. A very tragic period. You’ve got to say that some of these guys pushed the envelope and lived their lives to the fullest, and others just didn’t get the chance to. So, you know, life is about tragedy as much as it’s about joy.

Do you think about your own mortality?

I believe that you’re here and nobody knows what happens afterwards. It could be something about our spirit that’s more than just our minds and our bodies, that there is something else. And that’s a beautiful thing. I’m not anticipating coming back. But whether you go to a different place, whether you go to another sphere…

Although I’ve never adopted a religion as such, that doesn’t mean I’m not spiritual. Part of what’s right about being in this world is that you care about other people but you also take a little care of yourself – and hope in some way that, yes, there’s some sort of meeting place where we can all meet up again. That would be nice.

Steve Howe's All My Yesterdays: The Autobiography of Steve Howe, is out now. Upcoming album Love Is is available to pre-order.

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.