Steve Rothery nearly caught fire the first time he played a gig with Marillion. “The career could have ended there and then,” he says matter-of-factly. That was 37 years ago. Marillion were still called Silmarillion, and making their debut appearance in front of one man and his dog (and a teenage Steven Wilson) at Berkhamsted Civic Centre in suburban Hertfordshire. But more on that story later…

In 2017, Steve Rothery and Marillion are still intact, and their impressive showing in the Top 100 Greatest Prog Anthems list illustrates the level of affection in which they’re held. “I think Marillion appeals to people who are looking for something a bit more… maybe a bit deeper,” offers Rothery. “Something you can sink your teeth into.”

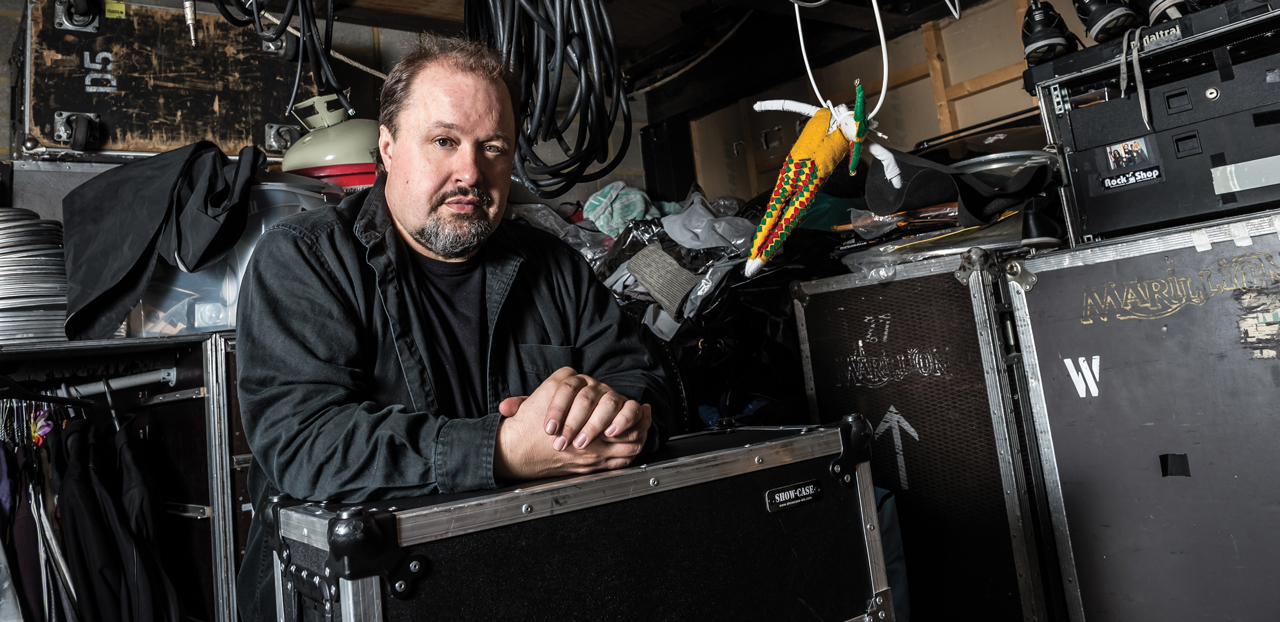

An uncommonly grounded musician – the term ‘rock star’ feels inappropriate – Steve Rothery has manned his corner of the Marillion stage with understated efficiency and gentle virtuosity since 1980. Not for him the drink, drugs and divorce papers that have felled some of his heroes and contemporaries. “Everything has a price,” he says philosophically.

Rothery is talking to Prog from Aylesbury, the Buckinghamshire town celebrated in Marillion’s debut single, 1982’s Market Square Heroes (that one’s not in the Readers’ 100). The 57-year-old guitarist, songwriter and, one suspects, Marillion’s prog rock conscience, is a man still charmingly fascinated by music: his own and other people’s – especially Genesis and Camel’s. But where did it all begin?…

You were born in South Yorkshire and lived in North Yorkshire until you were nearly 20. Do you still consider yourself a Yorkshireman?

Deep down I probably do. I lived in Whitby until I was 19. But I’ve moved around so much since then, it’s all started to get a bit blurred. My daughter and now my son were at university in York, and I spend a lot of time there. It’s still one of my favourite places in the country.

What was the first music you remember listening to?

Like every one of my generation, I was exposed to The Beatles. My uncle still has a reel-to-reel tape recording of me singing a Beatles song, when I was three or four. Yes [puts on faux-serious voice], my earliest recording. But then I got really into film music when I was about 11 or 12.

What specific films?

I started listening to all the John Barry soundtracks for the James Bond films, and the score for The Dam Busters. I went deep into this stuff on vinyl. I also had an album called Space Experience by John Keating. I think it was one of the first synthesiser records. That record got me really interested in synthesisers.

Are you a frustrated keyboard wizard then?

Yes. I originally wanted to be a keyboard player. My parents considered buying a piano, but they couldn’t get one – it wouldn’t have fitted in the house. But after the film soundtracks and John Keating I got into rock music and guitars when I was 15 [in 1974].

What converted you?

I fell in love with Genesis after I heard The Knife on Alan Freeman’s Saturday Rock show. After that, I discovered Camel, Yes, King Crimson…

Don’t you think that Camel are the great unsung heroes of 70s prog rock?

Absolutely. Especially those early Camel albums. There’s something magical about those records – a very special chemistry. They were a big influence. Really, my guitar playing is a mix of [Camel’s] Andy Latimer, Steve Hackett and David Gilmour.

So you’re not shy about mentioning those influences.

I have no problem being compared to them at all. They’re the people whose music I grew up with. It’s funny, because I know Andy Latimer and Steve Hackett really well now. David Gilmour, though… Ummm…

Gilmour’s a bit more remote, isn’t he?

Yeah, he’s up there in the stratosphere.

What was the first song you ever wrote?

I can’t remember the name. I wrote bits and pieces when I still lived in Whitby. I had a band with a friend of mine who had a complete Beatles fixation. We were never going to get signed. I didn’t really start writing until I moved down south to Aylesbury and joined Marillion.

What was the first piece of music you remember writing in Marillion, then?

Probably a song called Close which later became The Web. Then there was another track called The Tower which became part of Grendel.

What was your debut Marillion gig like?

It was in Berkhamsted [in the Civic Centre, March 1, 1980] and a very young Steven Wilson was in the audience. This was when we were still a four-piece before Fish joined. Our original bass player Doug [Irvine] was also the singer.

Were you any good?

It was… er… great. There were only a handful of people there. Something went wrong with the pyrotechnics. There was too much and I felt this sheet of flame shoot up my back. I was just happy to be gigging. That was the dream then – just to play live.

Aylesbury Friars was one of the great music venues. Bowie, Genesis and Mott The Hoople played there in the 70s and Marillion in the 80s. What was it like when you first arrived in town?

It was still in its heyday when I moved down. The music was incredible, and there was a real sense of community. You would go there even if you weren’t nuts about the band playing that night. I remember seeing Camel on the /Nude/ tour and King Crimson on the Discipline tour. I also saw The Police there a couple of times. The bands playing there were sometimes out of all proportion to the size of the venue.

What was your first impression of Fish?

Very tall and very Scottish. I had no problem understanding his accent but not many people in the band could follow it. Obviously, he was very self-confident and very driven. You could hear his influences, but there was something distinctive about the way he blended them together. Even then he was a great lyricist. We knew we’d found the missing piece.

If Fish was very self-confident and driven, where did you fit into the band? How would you define Steve Rothery’s role in Marillion?

In the early days I suppose I was the main musical writer, but I’m not naturally a pushy person. I’m not ego-driven. My focus has always been the music. These days nobody assumes the role of leader. Marillion really has become a democracy.

You mentioned your son and daughter. How important is family to you?

Very. My daughter Jennifer is a songwriter and recently moved to Brighton. My son, Michael, is in his third year studying computer science. My wife Jo and I celebrated our 30th anniversary last year.

Thirty years is going some in the music business. What’s your secret?

Many things. Behaving yourself? Yes! [laughing] I married the right person, which is always a plus. Jo gave me a lot of love and support. Sometimes, when you’re away on the road, and you’ve got a young family, it’s like your partner becomes a single parent, and it takes someone quite dedicated to pull through that.

But is she a Marillion fan?

Yes, she really is. My son and daughter are as well. You get the sense everyone in the family understands the sacrifice. They get it.

You’ve always seemed like a very clean-living musician.

I’ve never been seduced by the rock’n’roll fantasy. That’s not what’s real for me. That’s not what life’s about.

You published a Marillion photo diary, Postcards From The Road, in 2016. Photography seems to be your only vice.

Yes. I’ve been interested in photography since I was about 14, when I used to wander around Whitby taking pictures. I had an old Zenit B SLR. Once I started earning a bit of money around the time of [Marillion debut album] /Script For A Jester’s Tear/, I got myself a Pentax. I don’t know what drives me to do it, but it’s something I love.

Are you like everyone else these days, though, taking pictures on your iPhone?

I try to take a camera with me. But I’ve dragged huge camera bags around the world over the years, and you get sick of that. There are many times when the best camera is the one you’ve got with you – and that happens to be your phone. It’s OK, as long as the light’s good. If not, you’ll struggle.

You mentioned your love of soundtrack music growing up. Is it true Marillion were offered the soundtrack to Highlander? You turned it down and Queen got the gig instead?

Yes, apparently, that’s what I was told. Yeah, it was a management decision not to do it. We were touring the world at the time on the success of Misplaced Childhood. So there was no time. Fish got offered an acting role as well around then. It was one of those great ‘What if’s.

Would you still like to do a soundtrack?

Yes. I did some music for an American PBS documentary about bullying [the Emmy-winning From Our Hearts in 2014]. So it would be great to do another soundtrack. It doesn’t have to be a big budget film – something interesting, maybe an art film.

What’s it like being mates with Steve Hackett when you’re an old Genesis fan?

We only became good friends about three years ago, and it’s very strange hearing these stories about Genesis’ old days when he’s one of the reasons I picked up a guitar. We go to dinner quite regularly, and it often ends up with my wife Jo and his wife Jo down one end of the table and me and Steve at the other, talking guitars and world domination.

Marillion played Cruise To The Edge in 2014 and 2015. How is it being stuck at sea with a bunch of prog rock fans?

It’s surreal – a bit Twilight Zone. Our fans are fantastic, but you are on a boat with all these people who share a common passion for this kind of music. And, let’s face it, there are not that many of those people in the world, so to put them all together on a boat does warp the fabric of reality. But at the same time, it’s a lot of fun, and we’ve met some lovely people.

Have Marillion ever had a mad fan or a stalker?

Very occasionally you get the scary ones. There was a girl in the 80s who used to write Fish letters in her own blood, and there was an American fan who you could imagine… er… having a John Lennon moment with. You have to be careful, but we been incredibly lucky.

It’s been almost 30 years since Fish left. There was bad blood and recrimination at the time. But what lessons have you learned since then? Is there anything you’d have done differently?

Funnily enough, not so much to do with when Fish left. But more to do with what happened a few years later after we sacked our manager, John Arnison. This was around the time we were signed with Castle Communications [in the late 90s and 2000s]. I made a point of trying to understand the music industry, because when you’re a musician in a band, that isn’t the priority – the music is. So I read a few books about how this industry I’d been working in for 20 years actually worked.

What did you discover?

It gave me some perspective on how crazy our situation was in the 80s. We were selling out stadiums and having gold and platinum albums, but we’d seen very little of the money. There were various frustrations and things happening that could have been resolved by someone with a bit more vision and a clearer head.

So what you’re saying is your manager let you down and you should be richer than you are?

Yes. We sold something like 10 million albums. We should all be in living in country piles with crunchy drives… But at the end of the day you have to look at where you are in your life, and put it all in perspective.

That must have hurt, though?

Yeah, at the same time, you can’t help but feel a little… annoyed.

What was your first impression of Steve Hogarth?

Steve’s music publishers Rondor sent us a cassette tape, and his voice reminded me of Paul Buchanan from The Blue Nile. When he came in though, we were rehearsing in [bassist] Pete’s [Trewavas] garage. Pete has cats and Steve is allergic to cats. So there was this short period when he sang a couple of things, and we were blown away by his voice, and then a lot of time spent talking outside in the freezing cold. When he was offered the job, he had to go away and think about it – which we found quite strange and more than a little arrogant.

Don’t you think his arrogance turned out to be a positive, though? Surely, better that than some Fish clone desperate to join Marillion?

Absolutely – and we auditioned enough of those to know that’s not what we wanted. But Steve had also had an offer to play keyboards for The The – who were ultra-cool back then [1989], whereas we were as far away from ultra-cool as you could get.

If Marillion are having an argument does Hogarth ever lose his rag and go, “Christ! I could have been in The The!”?

Ha! I’m sure he can imagine an alternative reality. But I think he’d gotten to the point where he was so disillusioned with the business he was thinking about walking away and becoming a postman in The Dales. In the end, it all worked out. We went down to the mushroom farm near Brighton to give it a go [write and demo 1989’s Season’s End], and the rest is history.

If music hadn’t worked out as a career, what job would you have had?

Probably photography. It’s the only other thing that’s called to me in a similar way to music. When our original bass player left, just before Fish joined, I went for a job interview at the National Film Archive in Aston Clinton [in Buckinghamshire]. That’s the thing that could have diverted me off this path.

There are several Marillion songs in the Reader’s Top 100. But if you were trying to convert a non-believer, what album would you play them?

The new one [2016’s F.E.A.R.]. Of course [laughing]. I honestly think it’s one of our best-crafted albums. /Afraid Of Sunlight/ is another one of my favourites – a fantastic collection of songs, each one so different and not a weak song on there. A lot of people also like Marbles.

F.E.A.R. was your highest charting album since Clutching At Straws in 1987. Is the tide finally turning for Marillion?

We have seen things slowly turn around. Maybe because we’re almost like the last men standing in the prog world. But I think you’ll always have that thing if you had big success thirty odd years ago. Some people will always associate Marillion with Fish. There are still some people who think Marillion are a Scottish heavy metal band.

When you first heard Radiohead’s OK Computer in 1997, did you not find it galling? There wasn’t much difference between, say, Karma Police and some of the songs on ’94’s Brave.

[Long pause] Yeah, it’s funny isn’t it when you see that photograph of very early Radiohead and there’s a Marillion poster in the background…

But you can see the comparisons? No offence, but you’re both groups of earnest men playing the same sort of music with what sounds like a lot of repressed emotion.

I know. But Radiohead managed to encapsulate whatever that ‘student band’ cool thing is, and it never seems to go away. I thought their new album [2016’s A Moon Shaped Pool] had some great songs on it, and there is a great creative force there. But it’s funny how some bands can do no wrong.

I get the impression that Marillion being called a ‘prog’ band doesn’t bother you?

For me, there’s only good and bad in music. Labels are meaningless, and the true meaning of ‘progressive’ is music without any self-imposed boundaries. It’s having the freedom to work outside the constraints of conventional song structure – almost like a soundtrack type approach to creating songs. It’s whatever you want to call it.

Almost every Marillion album since 2001’s Anoraknophobia has been crowdfunded. Were you always convinced it would work?

It was unheard of. But we had to try. Our deal with Castle Communications ended, we had to decide – do we sign with another small label or try something else? That’s when Mark [Kelly, keyboard player] had the idea: Let’s take control ourselves, mail the fans direct and see if they’d be willing to pay upfront. It’s one of the reasons we’re still around. Our fans want it – they want the ultra-edition of the new album.

Will there be another Steve Rothery solo album?

Yes. I will do another solo album next year, but this year I have another project I can’t talk about yet. It’s very exciting but I’ve got to make sure it’s going to work before I announce it. Prog will be the first to know.

When was the last time you spoke to Fish?

Quite recently, actually. We get on a lot better these days. We’re older and wiser and we all have a different perspective. Everybody’s calmed down, and everyone knows that the whole reunion thing is just not going to happen.

It’s really never going to happen?

No, it couldn’t ever happen. I understand why people keep asking, because of what it represents to them and their lives, but no. Steve Hogarth has a T-shirt – ‘The New Boy Since 1989’. We did four albums with Fish, but we’ve done 14 with Steve.

What’s next then?

Apart from my incredibly secret new project [laughing], the Marillion Weekends are coming up [in March], in Holland, Poland, Leicester… and Chile.

Hang on, so Marillion are officially big in Chile?

Yes. There’s a radio station in Santiago that plays us all the time. We’re holding the convention in the same theatre we play in – the Teatro Caupolican. Every time we play there, there are 4000 people going crazy from the first note.

And you’re still big in the holiday parks?

We’re doing Center Parcs in Holland. We did our first Marillion Weekend at Pontins, then we slightly upscaled to Butlins. Now we’ve gone completely upmarket to Center Parcs. We’re going up in the world.