Regardless of project or period, the one constant we expect from a Steve Vai record is white-hot virtuosity. From his 80s shift as Frank Zappa’s ‘stunt’ guitarist, through his blurred-fingers solo breakthrough Passion And Warfare (1990), to the ongoing G3 shredder tours, Vai has become a byword for unfeasible pyrotechnics. Or so we thought.

In a genius twist to the late-period script, the 62-year-old New Yorker has just blown the dust off Vai/Gash, an unreleased biker-rock album, recorded back in 1991 and featuring the kind of AC/DC-style riffing that a teen garage band could conceivably pull off.

Just as intriguing are the vocals, by Vai’s wildly charismatic biker buddy Johnny ‘Gash’ Sombrotto, who died tragically on the road seven years after the sessions

Presumably you’re happy with the Vai/Gash album?

I’ve been happy with it for decades. It’s funny, because in my career I’d occasionally have these bouts of creativity where I’d just stop everything I was doing, rip something out relatively quickly and then just leave it. Kinda like little bookmarks of my life.

This record was one of those. It came from a very simple desire to make music for myself and my friends when we were riding our motorcycles in the nineties. I was gonna sing it, which would have been a disaster. Then I discovered this voice inside of John Sombrotto – that’s Gash.

When you met him in 1990, Gash was a thirty-something biker. Tell us more.

I’ve worked with many colourful people: Dave Roth. Devin Townsend. Frank Zappa. Gash was unlike any of them. He was crazy, funny and New York to the bone; you have to know New Yorkers. Gash was so loveable. And a complete daredevil, beyond, beyond. He wasn’t into drugs, but if his devil-may-care attitude didn’t kill him – which it did – then being a rock star probably would have.

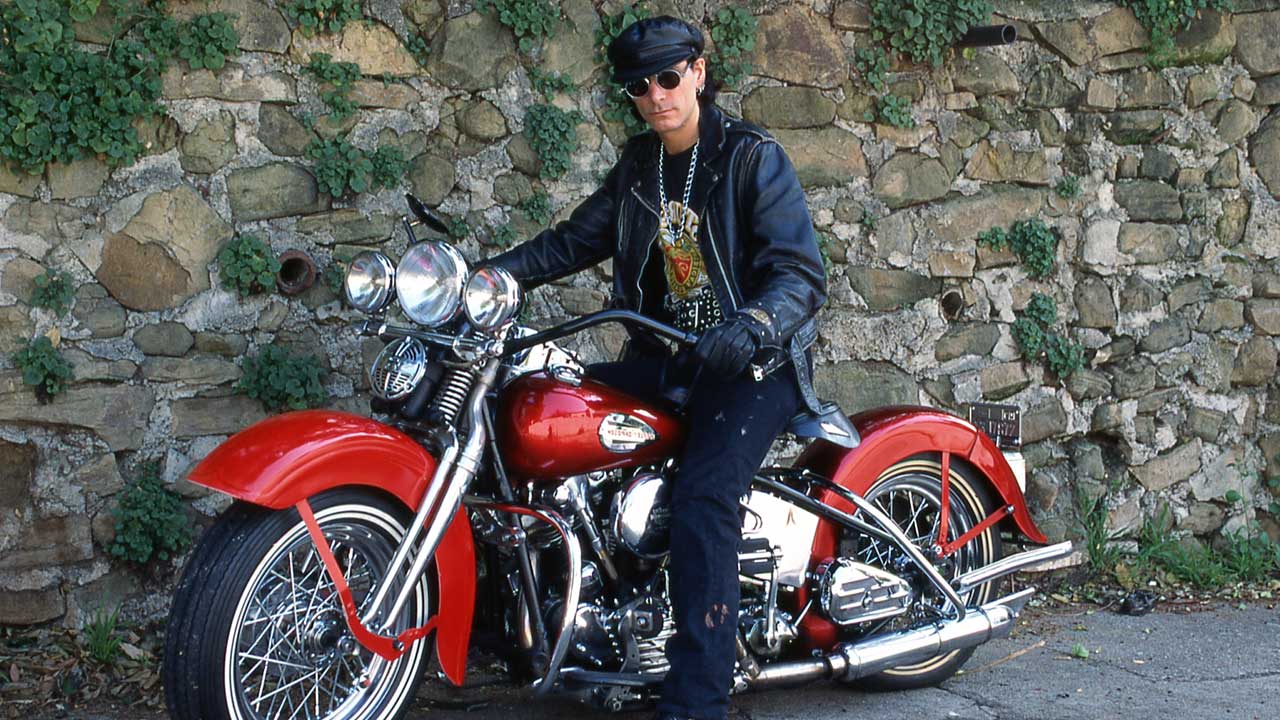

Gash looks pretty intimidating on the album sleeve.

He had that edgy kind of look. Gash had an accident when he was twenty-one. He was climbing these high-tension wires because he was riding his motorcycle and got lost and was trying to see where he was. The electricity went through his body and he fell sixty feet on to a barbed-wire fence. The treatment he went through was unbelievable. Sixty per cent of his body was burned. But he survived. His ear was totally burnt off. His whole neck. But his face was perfect.

What was your greatest adventure together?

Oh, man. I rode on the same motorcycle with him once and I’d never do it again. He’d be riding down the street, either standing on the seat in an iron cross, or with his feet up on the handlebars reading a magazine. If you look at the back of the album cover, he’s sat facing backwards, flipping the bird. He would do wheelies on Harleys. It might sound like hype or bullshit. Like: “Oh, there’s Vai trying to sell a record.” But you had to know this guy.

You would say: “There’s a fucking rock star.” And as far as a singer, I got him in the studio and I just couldn’t believe his voice. He had all the elements. In my mind, his potential was as great as any of the rock singers I’ve worked with or known.

This album presents a very different side of Steve Vai.

One of the ingredients that flipped my switch when I was young was massive guitar solos. But I chose not to do that on this record. I didn’t want to make it a showcase of Steve Vai guitar extravaganzas. There’s enough of that out there. I wanted it to be straight-ahead. Like: “There goes the solo, don’t blink.” There’s no noodling, no filler. Nothing is over-produced. It would never satisfy me for ever to make music like this, but it was certainly satisfying to do it once.

Why are you releasing this music now?

When John was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1998, I was just so disheartened. I put the project on the shelf. I created a blank about the whole period. Also, it was getting into the nineties and rock music was getting devoured. It would’ve been like throwing it to the wolves. So I just sat on it. But I kept listening to it, just enjoying the simplicity, the melodies, his voice. I thought: “Well, now’s a good time.”

Myself and John’s brother and girlfriend got together and pulled this thing out of the weeds. Before he died I only had eight tracks. One of them, New Generation, I wrote with Nikki Sixx. We gottogether once, many years ago, fooled around, wrote a song. I demo’d it and put Gash on vocals, and I ended up putting that on the record too.

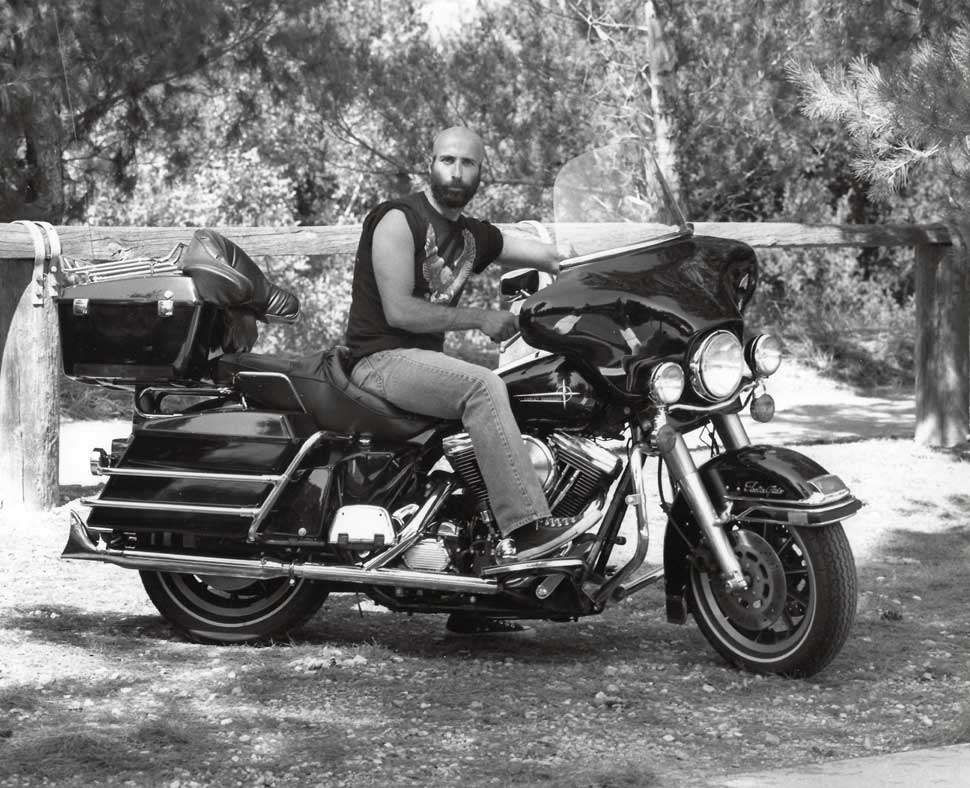

Your passion for biking isn’t that well known. How did it come about?

I was a motorcycle enthusiast as a kid. I’d build mini-bikes and go-karts. I could never afford a real motorcycle. My brother had a Harley, and when I finally started making some money I bought one and I was into the culture. I love the people. There’s a preconceived idea that bike-culture people are roughnecks and thugs. Of course that exists, when you start moving into bike gangs. But primarily they’re just good people.

Why is the motorbike so emblematic of rock’n’roll?

Well, it has the reputation as a bad-boy toy. And there’s that element of freedom. That has a huge impact. Just think how you feel when you get in a convertible, as opposed to a car. When people take back their freedom, they become themselves. You’re taking your power back, fanning the flames of your confidence. And that gives you a sense of dignity, purpose and worthiness. Like: “I am worthy of being myself, and I don’t care what anybody thinks and I don’t mind how they are.” That’s biker culture.