Steven Van Zandt: "Rock'n'roll is my religion"

Guitarist with Springsteen’s E Street band, leader of his own band, label owner, actor (Silvio Dante in The Sopranos), radio host… And there’s a lot more to Steven Van Zandt than that

In every sense, the man born Steven Lento has led a gloriously colourful life. At one time or other – and often all at once – these last forty-plus years, he has been a rock’n’roll musician, activist, actor, broadcaster and educator. Along the way he co-piloted two great bands out of his adopted New Jersey – the E Street Band and the Asbury Jukes – and fronted his own band the Disciples Of Soul. He has founded a record company, Wicked Cool, devised a globally-syndicated radio show, Underground Garage, and created not one but two pop-culture icons: strip-club-owning consiglieri Silvio Dante for David Chase’s groundbreaking TV mob saga The Sopranos, and his own bandana-sporting, gypsy-maverick on-stage alter-ego, Little Steven. When in 1982 he married his actress wife, Maureen Santoro, the couple were sung down the aisle by soul giant Percy Sledge, Bruce Springsteen acted as best man and the presiding minister was Little Richard.

“The trick is to be able to keep it all going simultaneously, but part of the joy of life is integrating all of your interests,” suggests the man better known as Steven Van Zandt, aka Little Steven. “It keeps everything fresh and you never get bored. Plus I found out a long time ago that if I focus on just one thing I tend to obsess and overdo it, whereas if I have five things on the go, that’s about right for me.”

It’s a hot spring day in Manhattan and Van Zandt is working out of his downtown office, an hour’s drive from his home in Jersey. Momentarily he is distracted by his wife dropping by and insisting that he take delivery of their King Charles spaniel, and then again by the question of whether or not he ought to retrieve his car sometime soon. “Am I going to need to go out again? Yes? No?” he asks of his assistant rhetorically. “Yes! Jesus, I was a fucking idiot to park it up in the first place.”

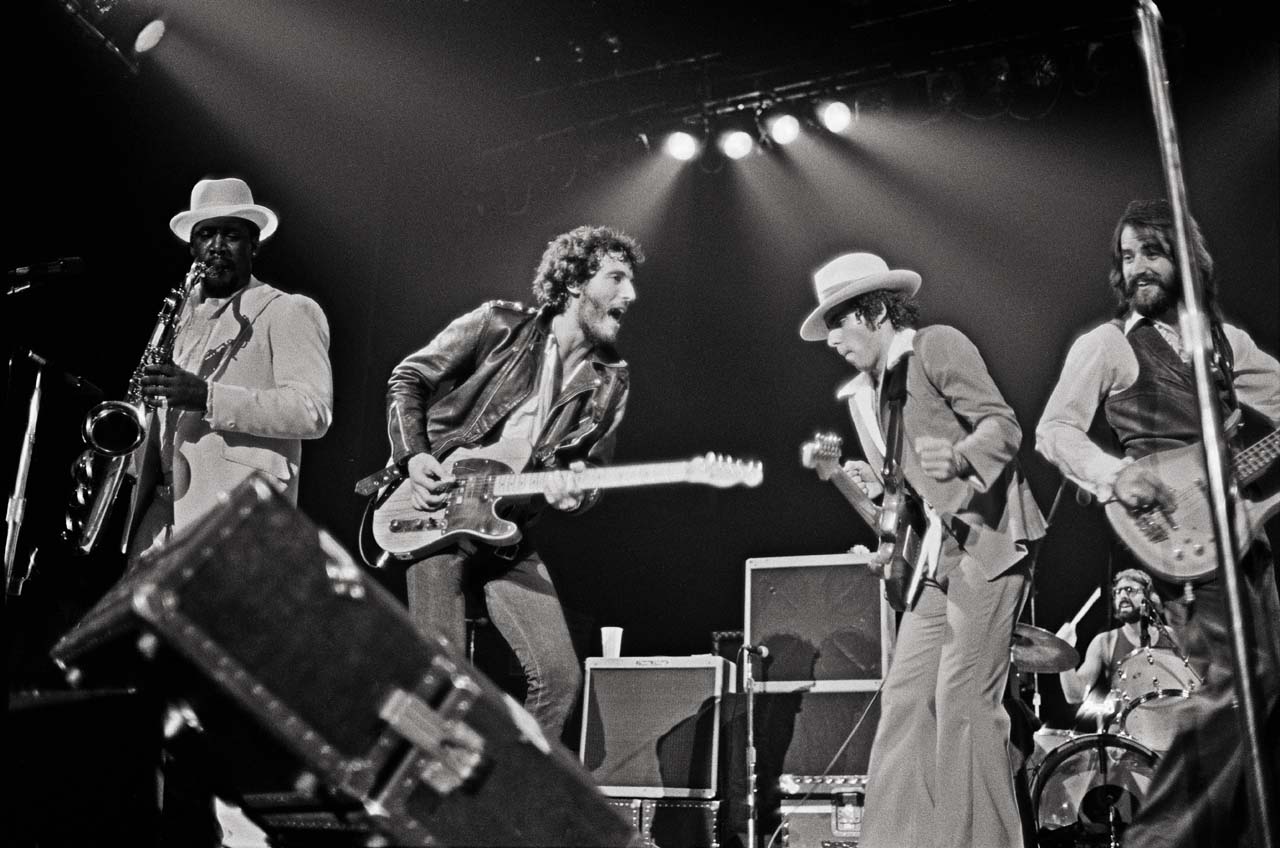

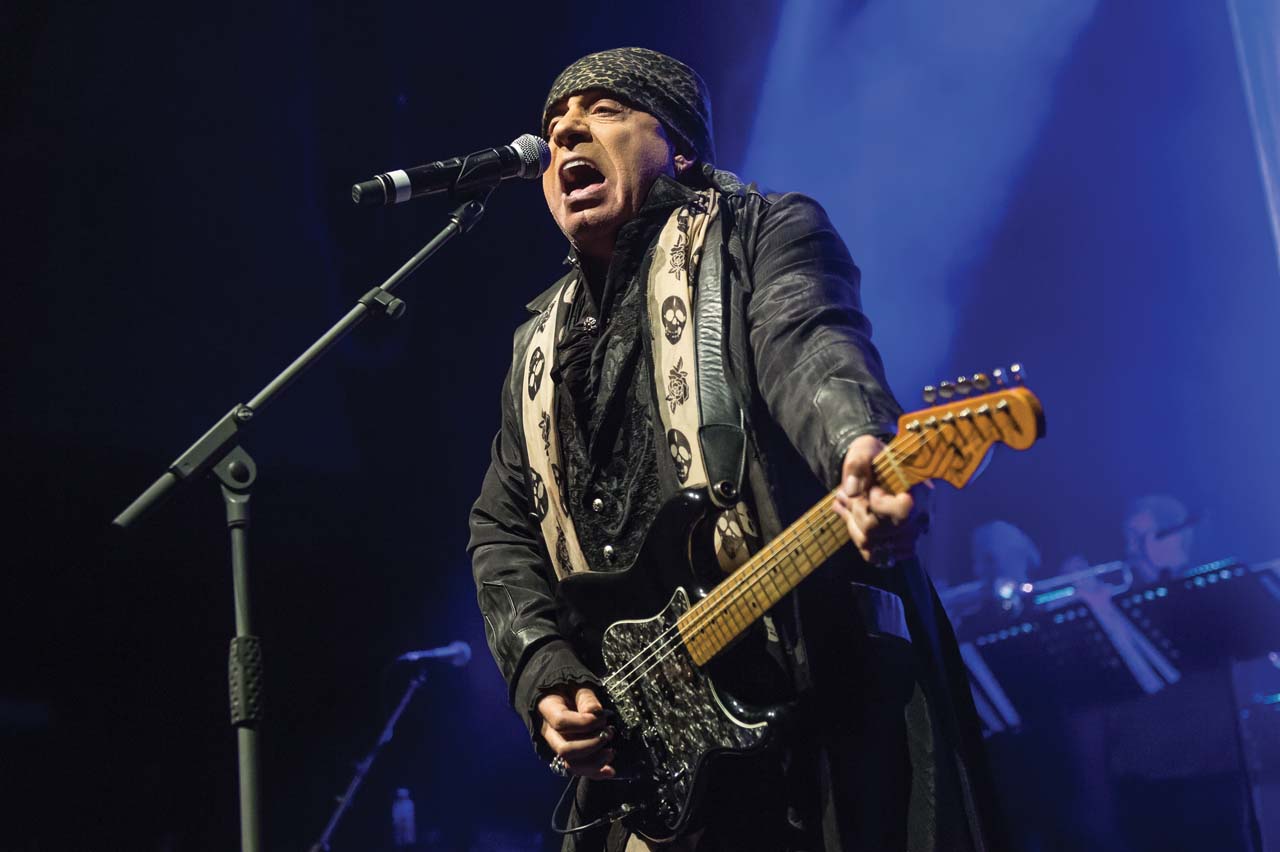

Domestic dramas aside, Van Zandt is very much in the room. Sixty-seven this November, he is still recognisably the outsize character who was generally first sighted sidling up next to Springsteen at the microphone in the mid-to-late 70s, the Boss’s left-stage foil and right-hand man. The voice and gestures are exaggerated, the yadda-yadda Italian-Americanisms together with animated chocolate-brown eyes suggest pathos and smarts. Fixed in place on his head is a bandana, black, the kind of which he has sported all this time – and not to hide premature baldness, but head scars sustained in a car accident as a teenager.

Get him on a subject that he is particularly passionate about – which is to say all of the above – and he lights up, his words spilling out a mile a minute. Right now the topic up for discussion is Soulfire, the sixth album he has made with the now 15-piece Disciples Of Soul and their first in 18 years. On it, Van Zandt revisits a collection of songs that he originally wrote, and invariably produced, for other artists including Southside Johnny And The Asbury Jukes and R&B stomper Gary U.S. Bonds. Altogether the record’s 12 tracks revel in the ‘New Jersey sound’ that Van Zandt did as much as anyone to hone. A strident, joyful, heart-racing, foot-pounding melange of rock guitars and R&B horns, the sound rose up along the Jersey Shore in the early 70s and went hot-rodding right on into the next decade and beyond.

“Without realising it I sort of created my own genre,” Van Zandt says. “These songs don’t belong in any one category or sit in a format. Which if you cared about the modern world would be a problem. Fortunately I really don’t. And the further we get from the roots of where they’re coming from, the more unique they sound.

“No doubt, over the years my own thing has got completely forgotten, and it was my own fault for walking away from it when I did. I got into a lot of other crafts, like acting and writing. Before you knew it, the best part of twenty years had gone by. So I’m starting over again and also trying to make amends.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Van Zandt was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1950, right on the cusp of the rock’n’roll era. His dad played a bit of trumpet, but there was nothing about his early childhood that foretold to him the world of possibilities just beyond the horizon. That wouldn’t come until 1964, and by which time his parents had separated, his mother had got remarried to William Brewster Van Zandt and young Steven had moved with them to live in Middletown Township, New Jersey. It was there, on the star-crossed night of February 9, that The Beatles were beamed into the family’s living room by the medium of television, specifically the Fab Four’s first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“The day before that, there were literally no bands in America,” Van Zandt recalls. “Day after, everybody had a band.”

He was no exception. In quick succession he formed The Whirlwinds, next The Mates, and then joined a third short-lived group, The Shadows, that was cast in the image of the British Invasion bands. He was sent home from Middletown High for having his hair too long, but graduated in 1968, and by then he had met the other ace young guitarist in the area, Springsteen, his senior by one year.

Van Zandt went on to play bass guitar alongside the elder hotshot in Steel Mill, a wannabe Allman Brothers Band, and then the Bruce Springsteen Band, aping Van Morrison’s big-band folk-rock. They built up followings in Jersey and nearby Virginia, but couldn’t break out to become more than just local big noises. Springsteen’s later songs refract this period in grand-romantic terms, carrying with them the sense that they were desperados on the run from their dead-end town and propelled by the idea that they were meant for better things. Ask Van Zandt now if the way that it played out was quite so evocative and his response is an eruption of laughter.

“No, no, not at all,” he elaborates. “There were only a dozen or so bands in the area that got out of the garage. We all became friendly, because it was a very underground thing and we were freaks, misfits and outcasts together. The Shore was a fucking wasteland. It was a ghetto. We had race riots. People had stopped visiting, so it was no longer a resort. Bruce and me, right away I think, realised we were a little different from the others, more dedicated.

“Slowly, everybody who had a choice took it: they went to college, or the military, or got a job. Eventually it was just him and me who were stood there, the last outcasts that didn’t really belong anywhere. People always tell me how persistent we were and stuck to our guns, trying to romanticise the whole thing. The truth is we couldn’t do anything else. We were completely incapable, so had no fucking choice. I would run into Bruce on weekends up in Greenwich Village, a bus ride from Jersey. We were out there trying to steal ideas, because New York City was a year ahead of Jersey and in those days it was all about what was coming next. Truly, every month a miracle would happen.”

Early in ’73, Van Zandt skipped town to go off and play guitar on tour with a doo-wop quartet out of Philadelphia, The Dovells. They criss-crossed the States, ending up in Miami, where Van Zandt picked out for himself a suitcaseful of lurid beach shirts. Returning in his new garb to frigid grey Jersey, he soon acquired the nickname ‘Miami’ Steve. In his absence, Springsteen had been signed as a solo artist to Columbia Records and was about to release his debut album, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. Van Zandt threw in his lot with another local hero, John Lyon, ‘Southside’ to his friends and supporters, and together they formed Southside Johnny And The Asbury Jukes, and took up residency at a club called the Stone Pony right on the boardwalk.

When it came time for the Jukes to venture out of Jersey, Van Zandt corralled a group of horn players to flesh out their touring sound and christened them the Miami Horns. For the next four years, on sweat-soaked club stages at first and then in the studio, and with Van Zandt as their chief songwriter, arranger and producer, the Jukes established the heart and soul of their home state sound. This burst into stereo life on the Jukes’ first album, 1976’s I Don’t Want To Go Home, and on the brace of joyous albums that followed: the following year’s This Time It’s For Real and Hearts Of Stone in ’78. According to Van Zandt, their trailblazing was once again born out of necessity.

“We were a bar band, so you had to make people dance,” he says. “Once upon a time people danced to rock’n’roll, and that was the same way that The Beatles and the Stones had started out. There’s just something magical about that combination of Motown, Stax, Atlantic soul and New Orleans R&B with rock guitar, and that became its own thing. By the time we got into the record business we had our own little niche, but even then it wasn’t hip. We had to make a living playing live, because we weren’t getting on the radio.

“Music is basically to do with five crafts, which are learning your instrument, arranging, writing, performing and recording. To me the main one of all those is when you get on stage and have to interact with other band members and an audience. That’s also the one that I see disappearing, because people are going straight from learning to play to selling their music over the internet. They’re skipping the most important phase of a career, which is to be a bar band.”

- The 10 best songs from Little Steven's Underground Garage

- Steve Van Zandt on Jimi Hendrix, Paul McCartney, Miles Davis and more

- TeamRock Radio app back on Apple’s app store

- Read Classic Rock, Metal Hammer & Prog for free with TeamRock+

Even before the first Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes record got off the ground, Van Zandt had found himself back in Springsteen’s fold. By 1975 his old friend’s first two albums had tanked and he was making his third under intense do-or-die pressure at the Record Plant in New York City. The sessions had dragged on for months, and when Van Zandt dropped by one evening, he found Springsteen, his manager Mike Appel and co-producer John Landau agonising over the horn parts to most Jersey-sounding song on Born To Run, Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out. Van Zandt leapt in and arranged for them a Motown-kissed groove in ten minutes flat.

After that, Springsteen invited him into the E Street Band. Van Zandt expected his tenure to last no longer than it would take them to fulfil their immediate obligations, which were a handful of shows booked to warm-up the record. Instead Born To Run rocketed out of the gate and he was at Springsteen’s side for the next seven years.

“It was a big deal, my joining the E Street Band, because I was just as popular as Bruce was locally,” he says now. “So that when I called him Boss, people started to take it seriously. I just saw in him something that was special and that I didn’t quite have, and nor did anyone else.

“There were also certain things that he wasn’t so good at. Turned out I was a better arranger and producer than him. I’m a good songwriter too, so was able to help arrange his songs from that point of view. If I hadn’t been able to contribute so considerably, I wouldn’t have done it, because I’m not exactly the sort of person who works for someone else.”

On stage, Van Zandt was the driver of the E Street Band’s stupendously tight backbeat, and in the studio a voice of reason and counsel. Following the brilliant but bleak and troubled ’78 album Darkness On The Edge Of Town, Springsteen made him co-producer for his next album, 1980’s The River. Van Zandt’s imprint was evident on the greater part of that double record. After Springsteen flew solo for 1982’s Nebraska, Van Zandt was back in the producer’s chair for Born In The USA. That one was very much his kind of record, the band cutting it live in the room, and full of wide-eyed songs that hurried to their choruses, but he upped and left before it was even released.

While Springsteen had been labouring over the sparse Nebraska, Van Zandt had assembled a big band of his own, the Disciples Of Soul, and with them made a euphoric rock-soul record, Men Without Women. It hadn’t sold much, but he’d got enough of a taste of his own thing to want more. Also, he was going through a political awakening. In 1980 Ronald Reagan was elected President of the United States, and Van Zandt became appalled at how American interests were being expanded into the Central American countries El Salvador and Nicaragua. He poured that into a second album with the Disciples Of Soul, 1984’s excellent Voice Of America, and very specifically on pointed protest-rock songs such as I Am A Patriot and Los Desaparecidos.

In 1985 he threw his weight behind the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, and founded Artists United Against Apartheid to encourage other musicians to snub lucrative offers to play the whites-only, high-roller resort of Sun City in the country’s North West Province. Springsteen, Bob Dylan, U2, Run DMC and Tom Petty were among the 49 artists who joined him in performing Sun City, the song he wrote to be its rallying point.

It was nothing like the mainstream smash that another superstar-laden issue-song, USA For Africa’s We Are the World, was that same year, but Sun City nevertheless helped to bring apartheid into an unforgiving international spotlight. It also succeeded in raising greater awareness of the plight of its most compelling opponent, the ANC’s Nelson Mandela, then serving the twenty-first year of a life sentence at Robben Island jail. By the time Sun City was out, Springsteen was enshrined as the rock superstar of the 80s and Born In The USA was on its way to selling more than 30 million copies.

“Oh, you can’t be stupider than me,” Van Zandt says, again roaring with laughter. “That’s why I give the best advice in the world. Not on account of me being smart, but because I’ve fucked up in every way possible that a person can fuck up. Leaving the E Street Band when I did, it’s one of those things you look back on and say was a tragic mistake.

“Even still, I probably would not have done the South Africa thing had I stayed. That’s likely going to be the one accomplishment of my life that means something, so you can also look at it that way. Now, I don’t think it will be remembered, but I know that I made a considerable contribution to bringing down that government and getting Mandela out of jail. I feel like that is some justification for missing out on those tens of millions of dollars. Meanwhile, as I was sneaking into Soweto for a meeting, hidden under a blanket in the back of a car, the E Street guys were all off buying their mansions.”

Van Zandt made further admirable records with the Disciples Of Soul, including 1987’s Freedom – No Compromise, its impassioned rock boosted by elastic Latin rhythms, and two years later a foray into Prince-style funk-rock territory with Revolution. The wider world barely noticed. Van Zandt now puts his gradual shift to the margins down to his own refusal to stick to one musical identity, and the fact that he didn’t have a manager to smooth his path.

He had all but vanished from view by the end of the 90s and when he got handed an entirely unexpected third act. In January 1997 he inducted proto-garage band The Rascals into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. Watching the ceremony on TV, writer-director David Chase was struck by Van Zandt’s comic shtick. At the time, Chase was looking to cast a sprawling Mafia drama that he was planning for the cable channel HBO. He called Van Zandt and invited him to audition for the lead role of antihero mob boss Tony Soprano. Never having acted outside of a school play and reluctant to shoulder the show, Van Zandt suggested instead a support character to Chase, Silvio Dante, who he had written up into a short story treatment of his own.

From when it was first broadcast in the US in January 1999 and over seven seasons of The Sopranos, Van Zandt, in a towering pompadour wig, delivered an acutely observed, finely sketched performance. His Dante was by turns funny, wry and chilling, in a landmark drama that revolutionised the scope of American television. He followed it up by writing, producing and taking the lead role in three seasons of another well-received mob drama, Lilyhammer, playing a hitman exiled through the Witness Protection Programme to the near-titular Norwegian town.

“I didn’t have any desire to be an actor, so I’ll be forever grateful to David Chase for persuading me otherwise,” he says. “I got a wonderful burst of energy that learning a new craft gives you. In The Sopranos I was able to use my relationship with Bruce as a model for Silvio’s with Tony. Silvio was the only character that didn’t want to be boss. He was comfortable with being the right-hand man.”

As fate would have it, just as The Sopranos was starting up, Springsteen, who had also gone off and tried to forge a fresh direction of his own with unspectacular results, decided to reactivate the E Street Band. Van Zandt re-signed up, and from 1999’s grandstanding Reunion Tour onwards, and despite the loss of core members Clarence Clemons and Danny Federici, they have gone blazing into a new century. Their singular achievement, Van Zandt maintains, is that they are not getting by on nostalgia, “or on people’s memories of what we once used to be. Bruce is still writing to an extremely high level, and we’re still able to do three-and-a-half hour shows, and we bring it every single night.”

Alongside his twin rock’n’roll and TV careers, Van Zandt has continued branching out. He launched his Wicked Cool label in 2006 to provide a home for venerated and emerging garage rockers alike. In 2007 he established the Rock And Roll Forever Foundation, devising a curriculum to teach the history of rock’n’roll and that is free for use in middle and high schools. And having switched on the radio and discovered that “rock’n’roll was gone from the airwaves”, since 2003 he has hosted Little Steven’s Underground Garage, which he devised and writes. Syndicated through the Sirius satellite network, the show goes out to a weekly audience of more than a million listeners in the US alone. Van Zandt now serves as an executive programme director at Sirius for both an extended Underground Garage channel and a second one that he subsequently devised for the service, Outlaw Country.

“People said rock’n’radio would never work in this day and age, but of course it does,” he says. “We have close to five thousand tunes on the Underground Garage playlist now and I pick every one of them. In that respect it’s an archive of sixty years of rock’n’roll and the roots of it, which was a true renaissance era when the best music being made was also the most commercial. Also, it’s giving new bands a chance to be heard and who would not have that anywhere else. Third, it allows me to show my gratitude to the greatest artists in the world and that I grew up with, like The Beatles, the Stones and The Kinks, not to mention the pioneers such as Chuck Berry and Little Richard. I’m also the only one that plays the Stones, Paul McCartney or Ray Davies when they have a new record out.

“Rock’n roll is an endangered species, and I think it’s really important that it continues to exist and be accessible to future generations. Hopefully what I’m doing on the radio will continue to live on beyond me.”

In the immediate future, Van Zandt hits the road with the Disciples Of Soul this month. Beyond that and juggling all of his other activities, he plans to do more TV for half of each year (he says he has seven different scripts currently in development), and tour in the summer with either his own band or Springsteen’s. For now, though, the dog is barking for his attention and he has a car to retrieve.

“Rock’n’roll is my religion,” he announces as he scoops up his keys. “It’s what I believe in and does all of the things for you that religion is supposed to. It’s inspiring, motivating, enlightening and educational. And, goddamn it, country to country, it’s still the greatest form of communication that we have.”

Soulfire is out now via UMC. Little Steven & The Disciples Of Soul play UK dates from November 4 to 16.

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.