“Once you realise your existence is futile and life is a random gift, you think, ‘I’m going to make the most of it.’ Life is meaningless – so embrace it”: Steven Wilson looks back at Planet Earth

His challenging return-to-prog album The Overview contrasts the collapse of a nebula with a bursting grocery bag in Swindon, all to illustrate that space is “nothingness; it’s scary; it’s death”

Buckle up and prepare to be taken on the ride of a lifetime. Steven Wilson is back with The Overview, an album that even he admits is prog. Comprising two tracks, the conceptual suite includes lyrics from XTC’s Andy Partridge and visuals that are out of this world. Prog visited the musician at home to get the lowdown.

There’s a phenomenon that affects astronauts when they travel into space and look back at the Earth, called the overview effect. “It’s reportedly a cognitive shift that occurs that’s to do with perspective and how they feel about their lives,” says Steven Wilson, a man who hasn’t been into space yet but has thought about the overview effect a lot over the last couple of years.

“It’s a mental perspective – quite literally having an overview of where we fit in time and space, or some inkling of it, and understanding in a split second of just how insignificant we are.”

It affects different people in different ways. When actor William Shatner, at the age of 90, travelled into space aboard the Blue Origin shuttle in 2021, the former Captain Kirk had an overwhelmingly negative reaction. “He said he’d expect to feel this sense of euphoria – but all he felt when he looked back at the Earth was a sense of death and nothingness,” says Wilson, as we sit at right angles on a pair of sofas in the open-plan kitchen of his north London home. “Isn’t that funny? Of all the people.”

Others have found beauty or even comfort in something that only emphasises our ultimately insignificant place in an unmeasurable, potentially infinite universe. Steven Wilson can understand this. “Your life is futile, it’s meaningless – and isn’t that a wonderful thing?” he says with more relish than it probably warrants. “And I do mean that. We spend so much of our time anxious, stressed, worried about things that sometimes we just need an injection of perspective.”

The idea informs Wilson’s new solo album, tellingly titled The Overview. Across its two lengthy tracks – one 23 minutes, the other 18 – it makes a dizzying, dazzling journey from the surface of the Earth to the most distant reaches of the universe. Musically, it’s the most recognisably prog album he’s made since 2014’s The Raven That Refused To Sing, even if it shares little with that record’s self-conscious homage to vintage prog.

Instead, the new work offers a much more contemporary version of the genre. “This record is definitely more informed by the genre hitherto referred to as progressive rock,” he says wryly at one point. Conceptually, it’s extremely ambitious. It starts with an encounter with an alien on some unnamed moor and ends billions of light years away on the very edge of the universe, taking in everyday dramas on the streets of Swindon, the destruction of Earth and such vast cosmic phenomenon such as the Omega Centauri, the Andromeda galaxy and the Eridanus supervoid.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It’s an album about the rise of social media and the death of curiosity, about the existential futility and beauty of human life. But mostly it’s about perspective. As Wilson puts it: “Sometimes being reminded how insignificant you really are in terms of time and space can create a sense of perspective, in a positive way as well as a negative way.”

The whole album is about cosmic vertigo. That’s what the overview effect is

Prog has already heard The Overview through headphones; but before we sit down for the interview, he invites us through to his home studio to listen to it through the ultra-high-end equipment he uses in his capacity as both a musician and one of the most in-demand Atmos remixers around. Sitting in a high-backed chair, bathed in unearthly wall-mounted mood lights, a screen flickering with lines and numbers before us as the album bounces around the room like it’s alive, it feels like we’re on the deck of a spaceship.

The album’s two parts has two personalities. The first, Objects Outlive Us (“The human story,” as Wilson describes it), is detailed and protean – a suite of music that shifts from acoustic passages to warm electronics, capped by an all-time-great solo from guitarist and regular Wilson collaborator Randy McStine.

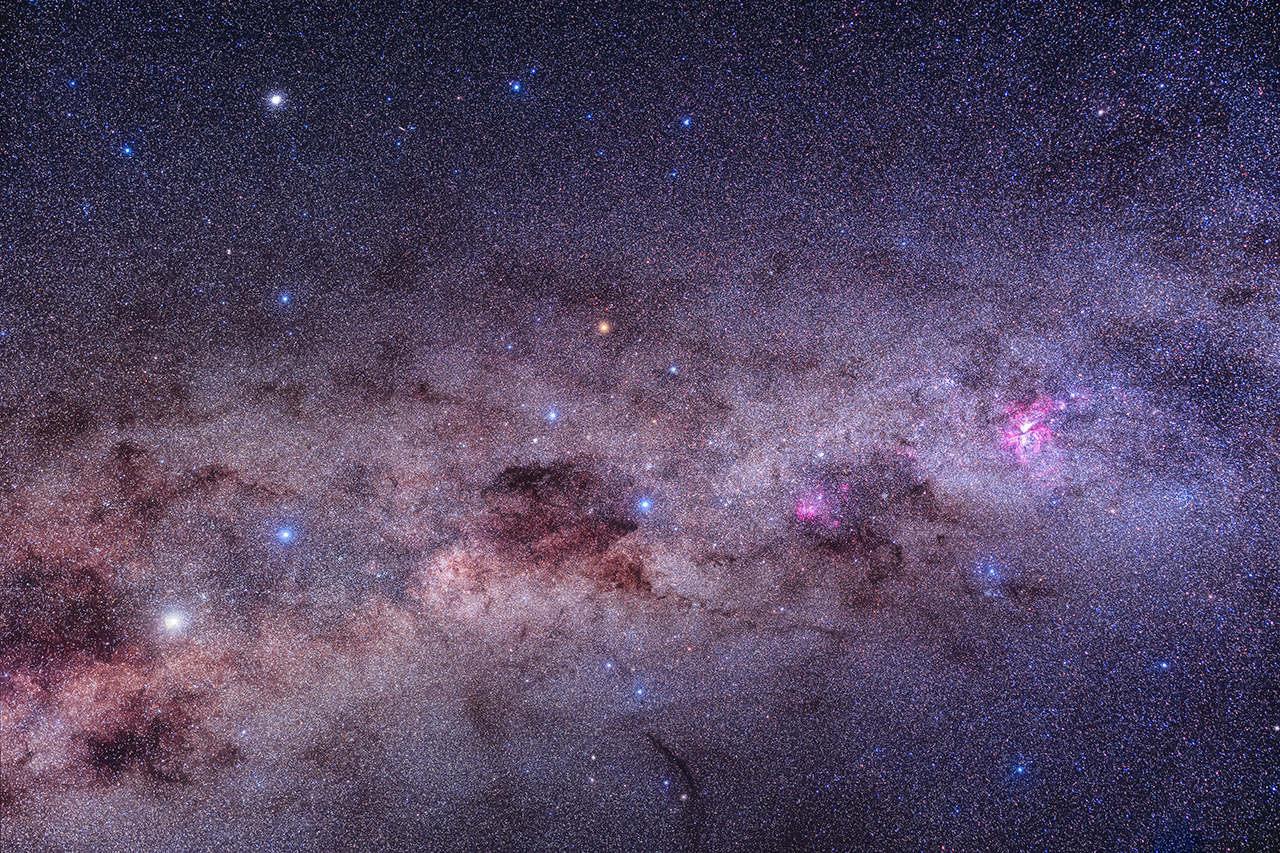

The second half, the 18-minute title track, is entirely different. More electronic, it evokes the sparseness and coldness of space – emphasised by the sound of Wilson’s wife, Rotem, dispassionately intoning numbers that correspond to increasingly vast distances from Earth and the cosmic phenomenon they represent. It may be a cognitive illusion of our own, but it evokes a sense of movement: a camera view of Earth as it gets more and more distant, pulling away until what Carl Sagan referred to as the “pale blue dot” vanishes; part of an ever-growing tapestry of galaxies and nebulae, as everything we know is erased by distance and time.

“What did you think of it?” asks Wilson, when Prog emerges, blinking, from the studio and touches back down on the sofa in the kitchen. It sounds brilliant, but it’s also thought-provoking, disorientating and existentially terrifying, in a good way. “I kind of want that,” he says. “The whole album is about cosmic vertigo. That’s what the overview effect is.”

The Overview is Wilson’s second solo album in less than 18 months, following 2023’s The Harmony Codex. He seems very proud of that fact. “It’s not quite up there with Taylor Swift knocking them out every year, but it’s not far off!” he says. “By the standards of musicians in their 50s it’s pretty good going.”

He admits he didn’t know what to do next after finishing The Harmony Codex. “Every time, I think, ‘How the fuck am I going to do another record? What the fuck am I going to do next? There’s nothing left in the well.’ I’m always thinking, ‘What can I do next that’s completely different?’”

These days we’re more interested in looking into the phone than we are looking up. It’s the enemy of curiosity

One of the things he considered was writing the music for an installation of some kind. He met up with Alexander Milas – former editor-in-chief of Prog’s sister magazine Metal Hammer, and founder of Space Rocks, a unique multimedia project that brings together science and the arts – with a view to collaborating on something. It was Milas who introduced Wilson to the overview effect. “It was the lightbulb moment,” he says. “I thought, ‘Oh Christ, there’s an album there, isn’t there?’”

Wilson has never had any particular interest in sci-fi, at least not in the kid-friendly Star Wars variety (the cold, existential sci-fi of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is a different matter). What he is interested in is space itself – the scale, the emptiness, the mindblowing incomprehensibility of the numbers involved. He starts reeling off stats.

“There are two billion trillion stars in the universe. That’s 23 zeros; I worked it out with Google! Earth has been here for four billion years, and we – as in humans of some sort – have been here for 300,000 years. That’s 0.007% of the time the Earth has existed.” How does that make him feel? “I don’t know,” he says, shaking his head like someone whose brain is in danger of short-circuiting from data overload. “I. Don’t. Know.”

He dove into research. Not books or movies, but facts. He spent a lot of time “mucking about” on an interactive website, Scale Of The Universe, which allows the user to zoom into the most infinitesimally small thing science can comprehend (the ‘string’ of string theory) and out to the most immeasurably large thing (the Hercules- Corona Borealis Wall, which stretches to an estimated 10 billion light years).

But it wasn’t just the daunting sizes and distances of these universal phenomena that were inspirational. It was the reality of space itself. “Space is very often portrayed as this kind of cuddly place, where people have adventures,” he says. “And the reality is the complete antithesis of that. It’s nothingness; it’s scary; it’s death. It’s fucking terrifying.”

Wilson’s journey to the stars began here in north London with a five-minute piece of music originally written for The Harmony Codex, but left out. “It was good, but I felt it was a bit too progressive for that record,” he says. The piece appears halfway through The Overview’s title track.

I told Randy McStine, ‘I don’t Comfortably Numb – I want something that’s similarly heroic and epic. Find a new way to speak in that vocabulary’

He admits he’s not the kind of person who “can go into a hotel room with an acoustic guitar and come out with something.” Instead, he develops ideas from piano melodies, drum patterns or keyboard textures. Lyrics, he says, slow down the flow of music. “They always come at the end. I can’t stop to write lyrics.”

These lyrics – and its overarching narrative structure – don’t feel like an afterthought. Musically and conceptually the pair of tracks are two sides of the same coin. “Objects Outlive Us is about what we do to the planet, juxtaposed with what’s going on on the other side of the universe. Then The Overview itself is basically about being lost in space, on the other side of the universe.”

Objects Outlive Us begins with an encounter with an alien, who asks, ‘Did you forget about us?” – plugging into another favourite Wilson theme: the idea that humanity has lost its curiosity. It also ties in with a recurrent bugbear: our obsession with screens, with gazing downwards at the internet rather than upwards.

“The first line on the album is, ‘I incline myself to space,’” he says. “The idea is that we no longer look up at the stars in the way that we used to in the 60s, when Kubrick made 2001 and everyone was obsessed with the Moon landing. These days we’re more interested in looking into the phone than we are looking up. It’s self-obsession; it’s narcissism – it’s the enemy of curiosity. Curiosity is one of the most undervalued human attributes. It’s what takes you to great music, to great movies, to other countries.”

For one sequence in Objects Outlive Us, Wilson enlisted the help of XTC’s Andy Partridge to write the lyrics. “The whole thing about Andy is that he’s brilliant at observing smalltown England,” he says. “I knew early on that I wanted a sequence that would be this juxtaposition of the triviality of human life with these nebulae exploding and black holes imploding on the other side of the universe. So I rang him and said, ‘I’ve got a challenge for you. I want smalltown soap operas juxtaposed with cosmic phenomena.’ And he said, ‘OK, I’m going to give it a try.’”

Partridge nailed the brief. That sequence, titled Objects: Meanwhile, offers pithy yet perfectly-drawn portraits of a shopper helplessly watching as her grocery bag bursts, spilling their contents in shapes that resemble star clusters; a distraught driver weeping in his car over the debt he owes as a star blinks out billions of light years away; or an elderly widow dreaming of dead spouses as “a nebula dives into our Milky Way.”

It disappoints me who people vote for, it disappoints me what they eat. But I think life is amazing – an incredible gift

“The idea was that you have these little soap operas in Swindon – because it’s Andy, obviously – which end with, ‘…Meanwhile, on the other side of the universe, this is going on...’” says Wilson. “Isn’t that fucking amazing?”

A subsequent section of Objects Outlive Us takes what Wilson calls “a nihilistic, doom vision of where we are right now as a planet”, before the remnants of humanity packs into an ark and heads for the stars. “The alien becomes our guide, and we end up literally floating in nothingness on the other side of the universe, billions and billions of light years away.”

Objects Outlive Us concludes with one of the album’s most transcendent moments courtesy of Randy McStine. The guitarist delivers a monumental solo, one worthy of David Gilmour or Steve Hackett. It’s the point of lift-off in more than one sense.

Wilson recalls: “What I said to him was, ‘We need to reinvent the classic rock solo. What I don’t want is Comfortably Numb – what I want is something that’s similarly heroic and epic. I want you to find a new way to speak in that vocabulary.’”

The result is a solo statement. It doesn’t sound like Comfortably Numb or Firth Of Fifth or any of the great 70s solos that defined the form, instead updating that heritage. Why didn’t Wilson play it himself? He laughs. “Honestly? I don’t think I’m good enough. I can shred a solo OK, but I bore myself. What’s beautiful about a soloist coming along is that they’ll give you something unexpected and make you rethink where the music is going to go. And that was what Randy did.”

If Objects Outlive Us sees humanity’s tiny, cosmically insignificant dramas playing out on the vast stage of the universe, the 18-minute title track flips things around. It features the aforementioned contribution from the album’s other notable guest, Rotem, making her third appearance on one of her husband’s albums, following The Future Bites and The Harmony Codex.

In a featureless, almost mechanical monotone that deliberately echoes HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey, she relates a series of increasingly large numbers followed by the proportionately enormous cosmic phenomenon, representing both their size and distance from Earth. ‘Size beyond one megametre... 10 to the power of six... Ganymede, Callisto, Wolf 359...’ she recites, culminating with: ‘Size beyond one yottametre... 10 to the power of 24... Virgo super cluster, Eridanus supervoid, supercluster complex’, the latter one of the most distant structures discovered in the universe. It’s a lesson in contrasts.

I love so many different kinds of music that I didn’t think of myself as having a very limited pool of inspirations

“It all goes back to perspective,” he says. “That idea of cosmic vertigo. And that, by the way, is exactly why I think we’ve invented religion. Religion is a classic manifestation of cosmic vertigo: ‘I don’t understand my place in the world, I don’t understand the point of my life, there must be a reason for this – let’s invent religion.’ What amazes me is that it still clings on as an idea in such a big way when you think we should have evolved beyond that. To even understand even the very simplest, most basic facts about space, should be enough to disabuse anyone of the notion of God. But apparently it doesn’t.”

If he sounds disappointed by culture’s inability to let go of outmoded models of thinking, that’s because he is. “I’m a 57-year-old man – of course I’m disappointed,” he says with a laugh. “It disappoints me that people still believe in bullshit; it disappoints me who people vote for, it disappoints me what they eat. But at the same time, I think life is amazing. I think it’s an incredible gift.

“I look around the world and there’s so much to be fucking depressed and miserable about. But there’s also so much incredible stuff that we do – unbelievable, beautiful, inspiring, dazzling. It’s possible to hold those two things simultaneously in your mind: the logical and the illogical, the good and the bad.

“And one of the things The Overview is about is that once you realise just how futile your existence is, and what a random gift life is, you think, ‘OK, fuck it, I’m going to make the most of it.’ That’s the positive side to it. At the end of the day, your life is meaningless – so embrace it.”

He pauses. Suddenly the interstellar camera stops, reverses. In a fraction of a heartbeat, we’ve flashed back across tens of billions of light years and we’re back on a sofa next to a window in a kitchen in north London. “Do you want another cup of coffee?” he asks. In the face of a vast, unforgiving, incomprehensible universe, yes, another coffee would be nice.

If there’s a thread running through Wilson’s eight solo albums, it’s that no two sound the same. The Steven Wilson Solo Musical Universe stretches from the abrasive guitar rock of Insurgentes to the graceful art-pop of To The Bone, from the robots-dancing-on-a-production-line electronics of The Future Bites to the wilfully boundless multi-genre exercises of The Harmony Codex.

The Overview finds him broadly circling back to the same territory he explored on 2014’s vintage prog homage The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories), albeit in markedly different form. “To pre-empt a question you’re maybe going to come to, why have I gone back to a more progressive style?” he says. “It’s because that’s what the theme suggested to me. It all comes down to this idea of perspective. That immediately suggested something more long-form, more conceptual and, dare I say it, more progressive.”

Porcupine Tree ahead of our time in the way we infused big metal riffs with classic songwriting and electronic sound

So, you’ve made a prog album. “It’s definitely going to appeal to...” he starts to say, then laughs. “It’s a prog record, yes.”

Having to prise this admission out of Wilson shouldn’t be a surprise. His relationship with progressive music runs deep – he’s said that Pink Floyd were fused into his DNA as a child after being introduced to them by his late father. But it’s also a complicated one. His solo career has often seemed like an exercise in running away from the idea of being pigeonholed as a prog musician.

“Did I run away?’ he asks, almost to himself. “I guess I did. I think the simple answer is that I don’t think of myself as a generic artist. This is a progressive album, and I’ve made progressive albums before, but I never thought that was the extent of what I could do. Perhaps part of making records like The Future Bites, which is an electronic pop record, or The Harmony Codex, which is a fuck-knows-what- kind-of-record, and coming out the other side is that I feel like I can make a progressive rock album again and people aren’t going to say, ‘That’s all he does’ –because they know that isn’t all he does.”

Prog wonders if being pigeonholed was really that much of a fear. He thinks for a couple of seconds before answering. “It’s more that I listen to so many different kinds of music and I love so many different kinds of music that I didn’t think of myself as being someone with a very limited pool of inspirations. So when anyone would tell me that I’m a ‘progressive rock’ artist... yeah, I guess I’m in that tradition, but I also reserve the right to go off and do dark ambient drone music or noise music or electronic pop music.

“I’ve always kicked against the notion of being a generic artist, of being associated with only one genre and one musical style,” he continues. “The great movie directors are able to go from making a costume drama to a horror movie to a ghost movie. They can go from one thing to another and no one thinks that’s off. Do that as a musician... it’s hard to redefine yourself with every record you make. And yet the artists I admire the most are the ones that have done that.”

It sometimes seems like Wilson has a healthy disregard for what other people want from him. He doesn’t go out of his way to alienate his audience, but he certainly doesn’t pander to them. “I love the idea of confronting expectations,” he says. “People think I deliberately go out of my way to upset prog fans! There’s a small group of hardcore fans I probably would be very happy to upset: ‘If it doesn’t sound like it was recorded in a basement in 1972 with Mellotrons, it’s not proper music and people need to be educated to enjoy it.’

“Those people, I would be very happy to upset any day of the week, and I’ll go out of my way to upset them. But generally, people who like more progressive, more conceptual rock music, they’re much more open-minded than perhaps even they give themselves credit for.”

Still, it seemed like he did lose some of your audience with To The Bone and especially The Future Bites. Is that how it felt? “For sure.” DId that bother him? “Of course,” he admits. “It’s not my goal to lose people. But there is another side to that coin. The Future Bites got me so much more attention in parts of the media that had never paid me any attention before. While it wasn’t resonating so greatly with my fanbase, it was getting phenomenal reviews with the more indie, hipster people that hadn’t really paid attention to me before.

If people don’t like everything I do, they’re still curious. Even if it’s to moan that you’re not doing what they wanted

“Certainly this time around there are people paying attention to this record that would never have paid attention to The Raven 10 or 11 years ago, and that’s because I’ve made songs like King Ghost and Personal Shopper. Not that it was intentional – I want to make that clear. There was no masterplan: ‘I’m going to make this record and get more press on my side.’ The thing is, I don’t mind if people don’t like what I do. It’s when they dismiss it as trash...” That doesn’t really happen very often, though, does it? “I don’t know,” he says, shrugging. “I don’t read stuff online.”

A cynical view of The Overview – one that glosses over its brilliance – is that it’s a deliberate move to claw back some of those more dug-in prog fans lost through The Future Bites. “No, absolutely not,” he says emphatically. “Because if I were to do that, I would have done it with The Harmony Codex. It’s hard to answer that question, because on the one hand I’m aware that it’s going to happen; on the other hand it really wasn’t a motivating factor.

“I’m sure some people might draw that conclusion, but anybody who knows me well enough knows that wasn’t the case. Also, with my next record – whatever it is – I’ll be looking to do something completely different. Which will probably alienate people who like this record!”

Even before The Harmony Codex, Wilson reasserted his prog bona fides with the surprise return of Porcupine Tree after an 11-year hiatus with 2022’s Closure/Continuation album and a hugely successful tour. Where The Harmony Codex was written “before, during and after” the reunion, the new one is the first Wilson album to be written since then. Did the Porcupine Tree comeback feed into The Overview in any way? “It must have done, but I can’t tell you how, not in a conscious way,” he says. “Did I feel more liberated? No, because that’s never been an issue for me anyway.”

The subsequent Porcupine Tree tour was a huge deal. Venue for venue, they played to more people than Wilson does as a solo artist. “For sure,” he says. Is that annoying? “Not at all. The reality is that Porcupine Tree came back and played to more people than Porcupine Tree did. When we stopped in 2011, the pinnacle was one night at the Royal Albert Hall.

“I played three nights at the Royal Albert Hall as a solo artist. When Porcupine Tree came back, it leapfrogged all that and we sold out Wembley Arena. I’m going to take a little bit of credit for that myself, having carried on as a solo artist. And Gavin Harrison being in King Crimson helped too.”

Does that mean people want a shot of nostalgia from old music more than they want to hear new music? “I’m not sure about that, because we made a point of playing the whole of the new record,” he says. “Everyone who comes to a show wants to hear their favourite songs; of course they do. That’s true of my solo shows – people want to hear The Raven That Refused To Sing and Harmony Korine.

“Maybe I’m flattering myself in saying this, but Porcupine Tree were a little bit ahead of our time in the way we infused big metal riffs with classic songwriting and electronic sound design. It was very unusual when we were doing it back in 2002, 2003. Since then it’s started to grow. A lot of bands sound like they have been quite influenced by us. In fact, I know there are a lot of bands who have been influenced by us.”

Porcupine Tree haven’t got any plans, but I think we’ll make another record. We really enjoyed making the last one

The surprise return after a decade of radio silence defines Wilson’s modus operandi. It’s not that he’s unpredictable – that suggests chaos and randomness, which don’t seem to be his style. It’s more that he thrives on confounding predictability, partly from fans but mostly from himself. Pretty much the only thing that links his solo albums is the impulse never to repeat himself. It‘s why he’s come back to prog – or at least a version of it – on The Overview.

“I always like to do the unexpected,” he says. “‘I always like to do something different to what I did before. I do really push my audience around, and for whatever reason – with the exception of the prog hardcore that have drifted away – they’ve stuck with me. Even if people don’t like everything I do, they’re still curious. Even if it’s to moan that you’re not doing what they wanted.”

There’s another thing that defines Steven Wilson, which is the fact that, in mainstream terms, he’s been on the outside looking in for the whole of his career. He’s had huge success within whatever fields he’s chosen to operate in, but he’s never crossed over to reach an entirely new audience. He’s one of the most successful cult artists on the planet, and there’s sometimes a sense that this frustrates him.

“Would I love to be embraced by the mainstream? I’d be lying if I said I wouldn’t. Would I love to have a Grammy, finally? Yes. Would I like to have the same level of respect afforded to Radiohead or feel like Thom Yorke digs what I do? Of course I would. Why am I never considered in the same breath as Thom Yorke? ’Cos I’m not as talented, I know that. Or it could just be down to the music I make. But yes, there’s a part of me that does crave that – the part of me that looks at Pink Floyd or Radiohead and says, ‘They never compromised and they’re household names.’”

On the other hand, you’ve done pretty well without mainstream approval. “Yeah, I’ve done alright. But wherever you are, you’re always looking in the distance at something you can never get to. You’re always looking at the horizon, and when you get there you’re still looking at the horizon. You can never reach it.”

On the near horizon for Wilson is a run of UK and European dates in May and June, including four nights at the London Palladium. Remarkably, it’s his first solo tour in seven years. He’ll be playing The Overview in full, together with a set of solo songs he says “will be informed by the style of the new record.”

So, a prog set, then? “I didn’t say that,” he replies good-humouredly. “But I think Prog readers will be happy with the set. I’m going to be doing more long-form tracks. That’s not a cynical thing – it feels like the right thing to do.”

And further out in the Wilson universe? It’s too early to think about a new solo album, but there will be one at some point. He’s not opposed to the idea of another Porcupine Tree album, either. “We haven’t got any plans, but I think we’ll make another record,” he says. “We really enjoyed making the last one, partly because nobody knew we were doing it. Everybody thought the band had gone away forever. We had so much fun, just the three of us without any agenda.

You can never second-guess what’s going to do well and what isn’t. So just do what you want

“One of the things we said at the end of the Closure/Continuation cycle was that if we were going to make another record, it would have to be something different that we feel is exciting. So yeah, I’d be surprised if we didn’t make another record.”

Given The Overview was seeded by a conversation about space, so Wilson is keen to dive deeper into that world. He invited astronomer Dr Stuart Clark – a member of prog rockers Storm Deva – to a recent Atmos playback of the album, and would like to involve astronauts with their experience of having gone into space. “Imagine someone who has actually experienced the overview effect talking about it,” he says. He has plans to visit an observatory in Chile to look first-hand into the cosmos.

Any musician could conceivably do this. What sets Steven Wilson aside is that he’s actually thinking about doing it. In a world where success is measured in streams and views and the luck of the algorithm, there’s something to be said for turning left when everyone else turns right. The sky isn’t the limit. That’s the whole point.

“Just be emboldened to do what the fuck you want,” he says. “These days, you can never second-guess what people want or what’s going to do well and what isn’t. So just do what the fuck you want. Being able to do that, that’s got to be the measure of success, right?”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.