At the end of the Tusk tour in 1980, Fleetwood Mac was over. Blown away on the tides of cocaine, money, madness, and a bloated double-album that appeared to do everything it could to distance itself from the winning, grinning, sinning So-Cal sound of Rumours.

Over-influenced by the sudden ascendance of punk, Lindsey Buckingham had cut his hair, shaved his beard and bent over backwards to try to bring Fleetwood Mac up to speed with the new now sound of the delusional late 70s. The irony that this was achieved in a $1.5 million purpose-built studio was apparently lost on him.

Now, in the aftermath of the relative commercial failure of Tusk, and a tortuous year-long world tour that had left all five members in a hurry to get as far away from each other as possible, prospects for any sort of follow-up were thin, to say the least.

Indeed, the next five years were to be so grim for Mick Fleetwood that by 1985 he had sold his mansion, his flash car collection, even all his gold and platinum records, and now slept on a cot in the back room of Mac producer Richard Dashut’s Laurel Canyon home. He was bankrupt, divorced, and so addled on coke that the only people he still spoke to on a regular basis were the voices in his head.

“I’d been down before, in the years after Peter Green left and we struggled to stay afloat,” he said. “But never anything quite like this.”

In 1985, the dogged keeper of the Fleetwood Mac flame – the man who had co-founded the group and been its driving force for nearly 20 years – found it almost impossible to imagine how he would ever fight his way back from this form of “extended hotel hell”.

How had it happened? How had things got to this?

If Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks had been the catalyst for Fleetwood Mac’s evolution from has-been British bluesers into Californian soft-rock exemplars – the magic sauce that nurtured the hits and reinvented the Mac’s grizzly old image – it was Buckingham and Nicks who used the early-80s, post-Tusk era to parlay new, more exciting solo careers for themselves.

Buckingham had sacrificed himself for Mac’s giant success for long enough, he now decided. It was time for him to go it alone, unbound by such trite demands as hit singles and release deadlines. He wanted to make art, and Fleetwood Mac was no longer the place for him to do it.

His next stop was Solo City – and a US Top 10 hit in his own right, Trouble.

“Mick was a little bit bitter about me leaving,” the famously strong-headed guitarist put it at the time. “But if Mick and I see each other, there’s nothing wrong. The chemistry is there – that’s what the band was all about in the first place.”

Indeed. And a statement that left the door nicely ajar for any future rapprochement.

Nicks, however, appeared to have other ideas. She was 32 in 1980, and ready for “a big new adventure”. She was also the biggest female singing star in the world, had recently taken on a new manager, the all-powerful Irving Azoff, also then manager of the Eagles, and destined to become one of the major music biz players of the century. When Irving told Nicks that now was her time to strike out on her own, she knew he was right.

“There’s the wild side to me and the free side,” she explained in 1982. “As I get a little older and a little wiser, there’s still the wild side that doesn’t want any discipline whatsoever in her life, and the part of me that knows the only way I can get to people is not to be so terribly out of control, to balance the two.”

Or put another way, if her solo career didn’t take off, she knew she could always go back to Fleetwood Mac. Only Nicks’s career did take off, her solo debut, Bella Donna, going to No.1 in America and selling nearly five million copies, and including three hit singles, with the first, Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around, becoming Nicks’s biggest hit song since Dreams four years earlier.

- Best record players: turntables your vinyl collection deserves

- On a budget? Here are the best budget turntables

- The best bluetooth speakers you can buy right now

- Best headphones for music: supercharge your listening

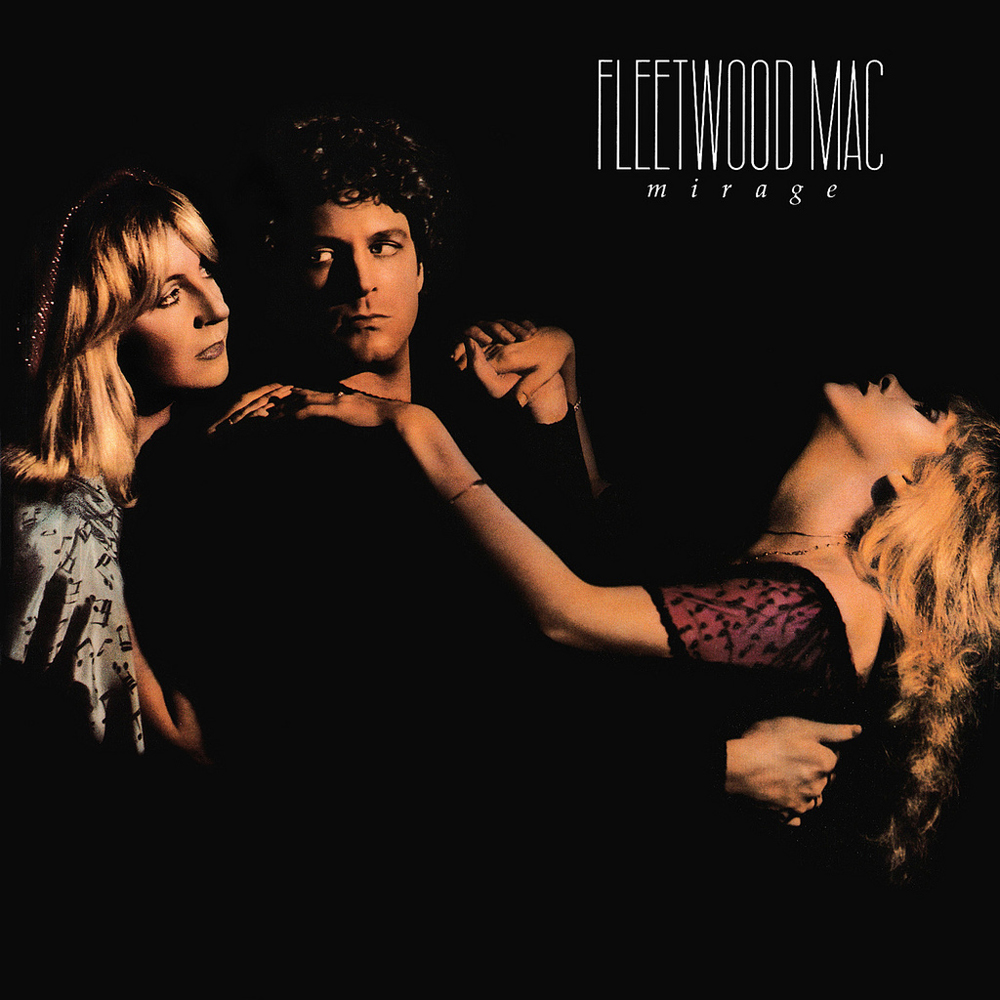

By 1982, as Fleetwood Mac gradually reconvened to make a new album, Nicks was so busy – planning a musical based on Bella Donna that would be “like the Othello of the eighties”; a ballet based on Rhiannon, or possibly a film version with Nicks as the titular heroine; a collection of children’s fairy stories, including her own The Golden Fox Of The Last Fox Hunt; and an autobiography full of “the love affairs, the heartaches, the tragedies, the incredible happiness” of her life with Fleetwood Mac – that she only had time to contribute three songs. One of those, That’s Alright, was a hand-me-down from her Buckingham Nicks days. Another, Straight Back, sounded like a well-meaning reject from Bella Donna. The third, though, Gypsy, was classic Stevie Nicks. Wistful, swirly and witchy, it gave the band another huge Rumours-style hit. That, plus the equally sublime McVie and Buckingham co-sung hit, Hold Me, elevated the new album, Mirage, to No.1 in the US. The album still didn’t sell even a tenth of what Rumours had done, but the Mac were back – like Tusk and coke and infidelity and deep pockets had never intervened. Well, almost.

“When I’m writing my songs, or just writing in my journal, I feel like the spirits are right here in the room with me, helping guide my hand,” Nicks told me one night, reclining on plush sofa cushions at her candlelit Hollywood Castle home. “Not ghosts, more like… good feelings. Strong emotions, from the past, from the future.”

Emotions that she wasted no time putting into her second solo album, 1983’s The Wild Heart. Mirage may have reestablished Fleetwood Mac as a commercial force, but it did nothing to discourage Nicks, Buckingham and now Christine McVie from instantly moving on to solo projects once the subsequent tour – just 29 shows in two months – was over.

Buckingham quickly moved on to make his second solo album, Go Insane – quirky, poppy, unashamedly MTV-focused – which flopped. McVie had a minor solo hit with Got A Hold On Me, which was Fleetwood Mac by any other name.

The only one who was content to lie back in the shadows and wait for the heat to drop was John McVie. He did some old-pals-act, jamming with John Mayall and Mick Taylor, reviving memories of his Bluesbreakers beginnings. He became, in his words, “a gagster” around LA, whenever he could be bothered to stick his head out the door. Mainly, though, he hung out on his boat, soaking up the rays.

As before, Nicks was the only one of the band’s front three to score heavily solo. And the only one, ironically, to really move the musical board on from the classic floaty Mac sound. Collaborating with Prince on The Wild Heart – hence the preponderance of squelchy synths and drum machines – she had another top-five hit with Stand Back, lifting the album to double-platinum status. Similarly, the yet-more-platinum 1985 follow-up, Rock A Little, in 1985, and the top-four single Talk To Me.

But by now Nicks’s health – and decision-making – was faltering. Having inexplicably turned down the song These Dreams, written especially for her by Elton John lyricist Bernie Taupin and multi-star collaborator Martin Page, she then suffered the ignominy of seeing Heart take the writers’ second choice version to No.1. Her voice had also gone from lamb’s-blood cool to wrinkled cat lady, the result in no small part of her years of cocaine abuse. That and the brandy, champagne and a ferocious cigarette habit.

“All of us were drug addicts, but there was a point where I was the worst drug addict,” she would later recall of the period. “I was a girl, I was fragile, and I was doing a lot of coke. And I had that hole in my nose. So it was dangerous.”

At the end of her ’86 solo tour, she checked into the Betty Ford clinic, and came out with a repeat prescription for the tranquilliser Klonopin – given to her by a certain “Doctor Fuckhead!” she scowled – which she also then became addicted to. Word was she had to have rhinoplasty to fix her coke-rotted septum. She also suffered long bouts of chronic fatigue syndrome following the removal of her silicone breast implants.

“They made me very, very sick,” she told one writer. “I had them done in December 1976. I’d only been in Fleetwood Mac one year and I was getting a lot of attention. I had always thought my hips were too big and that I had no chest.”

Now her problem was no self-esteem.

Meanwhile, Mick Fleetwood’s problem was no anything. He had also tried for some semblance of a solo career, with The Visitor, No.43 in 1981, and I’m Not Here, which came and went in 1983 without troubling the charts at all. The latter was billed as Mick Fleetwood’s Zoo, named after his three-million-dollar pad The Blue Whale in Ramirez Canyon. “A huge house built around a pool,” which he said quickly “turned into a real zoo” of dealers, groupies and after-midnight shenanigans. Neighbours included Barbra Streisand and Don Henley, but the entourage at the house became “a pool of leeches”.

Now bankrupt to the tune of eight million dollars, by 1986 Fleetwood was desperate to get the Mac money machine up and running again. He began by re-establishing his personal relationship with Lindsey Buckingham. The guitarist, who’d recently begun preliminary work on his next solo album with Richard Dashut, invited Fleetwood – still living at Dashut’s house – to work on some of the demos.

“I had some ambivalence about Mick,” Buckingham confessed. “He was clearly into my album, and yet I knew he was to a substantial degree instigating this whole band thing. I couldn’t be mad at him, because Fleetwood Mac is his lifeblood, really. He’s spent his whole life trying to keep the ship afloat.”

When the sessions then evolved into a nascent Fleetwood Mac album, Buckingham allowed it to happen. “Everyone has said to me: ‘This is going to be a good thing for you,’” he said, acting nonchalant, “and, of course, you kind of are suspicious of their motives, too. I’m a suspicious guy.”

The truth was that, like the rest of the band – Nicks, excepted – Buckingham hadn’t enjoyed significant commercial success since Mirage four years earlier. He may not have been broke like Fleetwood, but he craved the kind of bright-white-lights attention a new Mac album would give him.

Christine and John McVie were happy to collude. Fleetwood Mac had been their lives. They wanted it to revive as much as anyone. As for Nicks…

The album, titled Tango In The Night – an oblique reference to the various forms of ‘tango’ the band members indulged in during the moonlit hours, aka ‘dancing with the ice queen’, ‘no blow no show’ etc – would eventually take more than a year to complete. Yet during that time Stevie Nicks spent less than two weeks in the studio. Then when she did, she was so bumped-up, yanked-down, spun-around that she found the process turgid, boring, a drag, man. “I can remember going up there and not being happy to even be there,” she later admitted. “I guess I didn’t go very often.”

In fairness, she had been on the road touring for some of the time, been in rehab for some of the rest of the time, but mainly she was simply ill. From the drugs, from the withdrawal, from the implant infection, from the life she now found herself living as he spiralled into her late-thirties, alone and vulnerable.

It’s all there on the three tracks she wrote for Tango, most notably Welcome To The Room Sara, based on her month-long stay at the Betty Ford Centre, where she had checked in under the name Sara Anderson. The line: ‘Front line baby/Well you held her prisoner,’ was in reference to her management company, Front Line, whom she now blamed for working her too hard – the classic rock star response to allowing money and fame, and all the ‘fun’ that went with it, to fuck them up. It’s there again in the dreary, feeling-sorry-for-yourself ballad When I See You Again, singing about ‘the dream is gone/So she stays up nights on end.’ Not much better was the funk-lite Seven Wonders, which Prince had perked up for her.

Nicks was so utterly absent from the Tango sessions that when she sat down with the band to listen to the first official playback she had a major freak-out because, she screamed: “It’s like I’m not even on this record. I can’t hear myself at all.” To which Christine McVie replied dryly: “We wanted you to sing on it too. But you weren’t here. Now why don’t you just say you’re sorry and we’ll work it out.”

At which point, according to Mick Fleetwood in his 1990 memoir, “Quite gracefully, Stevie capitulated in front of the whole band and we gleefully layered her vocals into the mix of the album. Stevie had been right after all, and so had Christine.”

In fact several of her vocal tracks had been deliberately taken out of the mix by Buckingham, because she’d been drunk when she did them. Instead he used a Fairlight sampling synth to assemble some of her vocals. “I had to pull performances out of words and lines and make parts that sounded like her that weren’t her,” Buckingham later claimed.

It was a shame, as the rest of Tango In The Night contained some of the Mac’s best work since Rumours. Family Man, a Buckingham classic originally intended for his solo album became one of the album’s six singles. He also wrote and sang lead on the album’s most insistent hit, Big Love.

Christine McVie was also back on winning form, writing and singing the album’s other huge hit, Little Lies, a song that would once have begged for a Stevie Nicks vocal, here delivered with all the sugared aplomb of a true pro. Ditto Everywhere. This stuff was radio heaven, the kind of fluffy cloud-bouncing singalongs the Mac could again now be counted on to keep the big wheels of the record industry rolling.

Released in 1987, Tango In The Night became the second-biggest-selling album of Fleetwood Mac’s career after Rumours, selling more than two million copies in Britain alone. Surely, even with doubts about Nicks’s health still in the balance, the late-80s would be a new epoch for the band now celebrating its 20th anniversary?

It was – but not in the way any of them would have liked. Because just as they were about to begin a nine-month world tour, in September, Lindsey Buckingham decided he couldn’t go through with it and abruptly left the band.

Cue panic, fury, bitter recriminations, and so many different versions of what happened that have come out over the years since that it’s almost impossible to know which tells the most truth. What everyone – even Fleetwood and Buckingham – seems to agree on is that Buckingham bailed because he just couldn’t stand the thought of going back on tour with a band that still believed in all the ‘old-school’ ways of life on the road: dusty rose nostrils, white-walled eyes, brandy of the damned tongues and hundred-dollar-bill shoelaces.

Promises were made to him, inducement offered, and then accusations and threats that culminated in Buckingham calling Nicks “a schizophrenic bitch” and throwing her over the bonnet of a car. “You’re a bunch of selfish bastards!” Fleetwood recalls the guitarist yelling at them as he left.

Afterwards, John McVie merely shrugged: “It didn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out this was gonna happen.”

But Fleetwood, the old trouper, who had dealt with Peter Green at his most psychotic, who had dealt with other prima-donna guitarists walking out in favour of solo careers, who had kept the creaking Fleetwood Mac ship on its unsteady but direct course for two decades, shouted everybody down. He gave it the old stiff upper and lip and announced: “We’ve got a bloody great record, and we’re gonna look like a lot of bloody idiots if we don’t go on the road. Let’s keep our momentum going and use it to find new people.”

And that’s what they did.

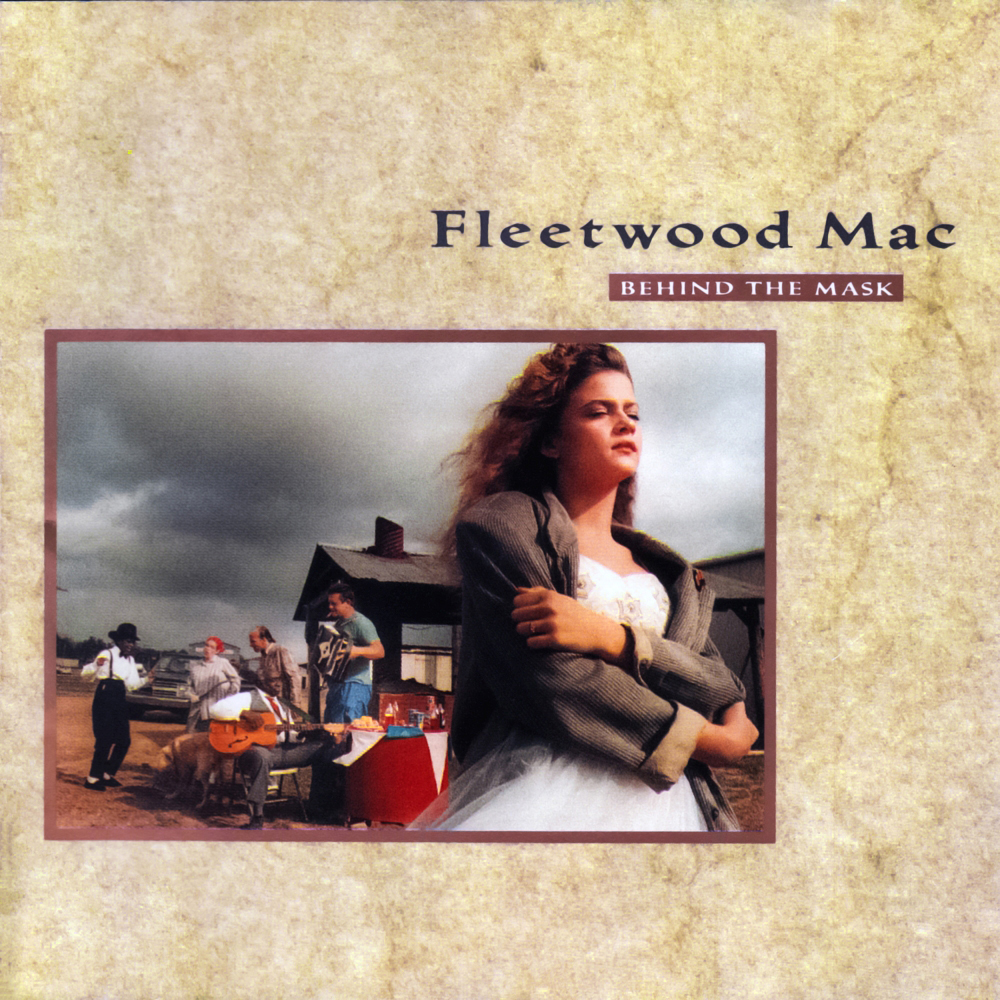

The 1990s would provide for a strange kind of afterlife for Fleetwood Mac. Fleetwood had desperately attempted to reinvent the wheel again, bringing in singer-guitarists Rick Vito and Billy Burnette to what was now the band’s eleventh line-up. But not even two guys could fill the tremendous Buckingham-shaped hole in the soul of the band, and though Fleetwood Mac toured successfully enough, chartering their own Boeing 727 aeroplane, the only album this line-up made together, 1990’s Behind The Mask, proved to be an artistic and commercial dud. On it there were no hits, no give-a-shits, and although it entered the UK chart at No.1 it dive-bombed thereafter and barely made the US Top 20.

Both Nicks and Vito split, and Fleetwood dug deep again, this time bringing in guitarist Dave Mason, the former Traffic/Hendrix/solo artist/session slinger, and Bekka Bramlett. The daughter of American duo Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett, Bekka was a leggy blonde 25-year-old who didn’t have a voice as distinctive as Nicks’s but she was almost half her age and sure looked good. This line-up also released just one album, 1995’s Time, which became the worst-selling Fleetwood Mac album since Penguin more than 20 years before. While on the road, the once magnetic Fleetwood Mac now found itself sandwiched onto a nostalgia package tour, between REO Speedwagon and Pat Benatar.

Buckingham’s next solo album, Out Of The Cradle had come out in 1992 – the same year Bill Clinton came to power on the back of Don’t Stop – but was a complete flop. Even John McVie put out a solo album in 1992, not that anyone noticed. For a while, it really did look like no one was getting out of this story alive.

No one – not even tunnel-visioned Mick Fleetwood – could have predicted that there would be yet more comebacks to come in the new century.

Instead, when I visited Stevie Nicks in the early 90s, at her home hidden deep in the Hollywood hills, I found the lady of the house in quiet repose. There was no ‘significant other’ present, just a bunch of giggling middle-aged female friends, all dressed to the nines in teeny-weeny cocktail dresses, drinking from fluted wine glasses, submerged in the dancing shadows of a house lit only by thousands of tiny candles.

She showed me round the house, every room, stairway, cupboard, hidey-hole, nook, cranny, even the bathrooms and toilets with their gold fixtures and fittings. Then we came to the bedrooms. There weren’t that many, actually. Then we got to her bedroom. She pointed to the four-poster bed on which sat dozens of Teddy bears, dolls and stuffed animals.

Later we settled on a couch and she told me how she believed in reincarnation. How she still loved Buckingham and Fleetwood – and others, right back to her earliest teenage crushes. She showed me her journal, which she had kept for years, full of dry-pressed flowers and her “secret thoughts” and poetry.

I asked if she could ever see herself back in Fleetwood Mac one day.

“No,” she she said, smiling. “Unless, you know…”

Oh, I knew.

How Rumours took Fleetwood Mac to the peak of their success

Every song on Fleetwood Mac's Rumours, ranked from Worst to Best

- The best budget wireless headphones: wire-free and wallet-friendly

- Best in-ear headphones: Louder’s top choice wired and wireless earbuds

- The best wireless headphones you can buy right now

- Take a look at the best true wireless earbuds

- Less noise, more rock with the best budget noise cancelling headphones