Definitions. In step: Moving in rhythm. In conformity with one’s environment. In step with the times.

In step: a reference to embarking on the Twelve Steps programme whose tenets include ‘We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable’ and ‘We came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.’

In Step. Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble’s last non-posthumous album, released in June 1989.

Six months after the album came out Vaughan addressed the Aquarius Chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous at the Ritz Hotel in New York and gave them his greatest unscripted message. “I started off my drinking and using career, oh I guess… early 60s, when I was somewhere around seven or eight years old. I grew up in an alcoholic family. My father was an alcoholic, and even though I saw the problems that alcohol caused in our family, I still found it attractive for some reason. I don’t know what that was; I was always a kid who was afraid I was gonna miss something.

“Somewhere along the line, I started trying to find out why my father would go back and continue to drink, even though every time he did I saw what happened, which was, big fights – you know, violence. We were always real scared of him. But he continued to do it anyway. I never… I never did understand what that was, until one day a few years later I realised that I wasn’t doing anything any differently other than making a little bit more money, and I’d added a few drugs to it, you know.

“I guess about seven or eight years old, I started stealing drinks either… well, my parents used to have these, these ‘42’ parties, and quite a few people would come over and they’d be havin’ their Tom Collins or whatever, you know. And when somebody wasn’t looking, I’d take one of the drinks and run to the kitchen, you know, an’ make them a new one. And, refresh their drink, you know. It’s just that I would refresh my memory about what it tasted like a lot of the time. I never really thought that it tasted very good or anything.”

Maybe now we see why Stevie Ray wasn’t on the dime when he came so close to death after playing the Pfalzbau in Ludwigshafen, September 28, on the German leg of his 1986 European tour. Not just him. Bass player Tommy Shannon was lying on a hotel bed sick with his own excessive cocaine and alcohol usage. He recalls how in the adjoining room Stevie was mumbling incoherently and vomiting blood and bile. Staggering to the phone Shannon pleads that an ambulance be called, and Vaughan is rushed to hospital with IVs in both arms. Miraculously he makes some sort of brief recovery, but by the time SRV and Double Trouble arrive in London to play the Hammersmith Palais on October 2, the group and most of the crew are wandering backstage like dead men.

Dr Vernon Bloom, who specialises in helping addicts withdraw – he’s had plenty of practice on Pete Townshend and Eric Clapton – has been contacted via Eric’s people and administered the relevant meds before Vaughan and company take the stage. The show passes without incident – it is neither great nor tragic – but in the gloom, just before he’s called back to encore, Vaughan slips off a gangplank and starts internal haemorrhaging. For the second time in days he is rushed to hospital. If this is a wake-up call, someone forgot to set the alarm.

The day after the Palais gig is Stevie’s birthday. To paraphrase Bo Diddley’s Who Do You Love – he’s got a tombstone hand and a graveyard mind. Just 32 and he don’t mind dyin’. Stevie’s habit is ridiculous. He’s snorting a quarter ounce of pure, pharmaceutical Merck flake cocaine a day, and necking a quart of Royal Crown scotch – at least. It doesn’t touch the walls. Dr Bloom discovers his patient’s already ruined septum is so corrupted that he’s taken to dissolving the cocaine in the whisky. X-rays reveal Vaughan’s stomach lining is rotting. Cocaine is crystallising in the man’s intestines. Bloom gives Stevie two weeks to live. Or you can stop right now and delay your death warrant. If you’re very lucky. But hey, it is his birthday. Bloom allows him a small plastic cup of champagne to celebrate and to wash down the Phenobarbital.

Stevie calls his mama Martha in Dallas and breaks down: “Ma, I’m real sick. I need help. I got to come home.” This isn’t great news. Martha’s husband Jimmie Lee Vaughan – Big Jim – is barely a month in his grave having succumbed to Parkinson’s disease, his own alcoholism and a working life spent around asbestos. In any case the tour is cancelled – though the press release only states Vaughan is unwell – and the guitarist flies home to enter the Charter Lane rehab centre in Atlanta, Georgia, while Shannon goes into their Austin facility. Drummer Chris ‘Whipper’ Layton is in marginally better shape, though no stranger to the drug and booze frenzy that has insiders comparing Double Trouble to the Allman Brothers Band at their absolute worst.

Indeed, Vaughan’s performances are so erratic in the period covering the Soul to Soul and Live Alive albums that a second guitarist, Derek O’Brien, is hired to supply some lead work on tour as Stevie’s fingers can’t talk the talk, while keyboards player Reese Wynans – ironically an Allman Brothers accomplice from Florida – joins the madhouse, ostensibly to add his 6 feet 6 inches of muscle to the group before they implode. Long tall Wynans is shocked by their business affairs and the amount of money they waste to line dealer pockets. Double trouble. Everyone seems more anxious to hang around expensive studios playing ping pong and waiting for the main man to arrive bearing goodies than actually playing the blues. “The drugging was so bad I was scared for the man’s health” Reese recalls. “Stevie was so worn down he obviously needed to rest, but it’s hard to stop working when you’re in big debt.”

Flash back to autumn 1986. Stevie Ray calls his wife Lenora (aka Lenny) and soul mate for the past 13 years, but she refuses to visit him in rehab. Turns out she’s been running round town with other men and spending her husband’s money on hard dope. Divorce papers go to and fro. Stevie comes home to find she locked the house, cut off the electricity and taken to hanging with ne’er do wells described by local insiders as “police characters, criminals and the scum of the earth”. And she took the dawg.

If there is solace in Stevie Ray’s collapsing world it arrives when he bumps into a beautiful brunette, a 17-year-old Russian émigré called Janna Lapidus. She finds him sitting head bowed on the steps of Wellington Town Hall in New Zealand where Double Trouble are performing in the spring before his final collapse. A rising star in the modelling industry, Janna goes on tour in Australia with the band, and she does visit Stevie in rehab, and they will become an item. Although she’s young, Janna has a wise head. During his London rehab the pair walk arm in arm in Hyde Park and pledge their allegiance to romance and loyalty, having seen an ageing couple holding hands by the Serpentine. Janna’s name is on In Step alongside the band’s saviour John Hammond. Janna is credited with turning Stevie’s life around.

But Vaughan turns out to have a strong constitution. On November 22 1986 the aborted Live Alive tour recommences and for the first time ever he plays clean and sober at Towson Centre in Maryland, with Bonnie Raitt.

It’s December 1988 when producer Jim Gaines gets the call asking does he want to produce the next SRV album? Based in San Francisco, Gaines’s main client is Carlos Santana, and ole Devadip knows Stevie well – they’ve played together. Plus, Gaines is a guitar guy. Vaughan asks him: “How do you feel about recording me when I’ve got 10 amps goin’ at once? Think you could handle that?” Gaines has trudged through the sludge with Carlos and Ronnie Montrose, who both use six or seven amps in the studio, so he agrees. “Why not? It sounds like a nightmare. Let’s do it.”

Just before Christmas, Double Trouble’s Epic Records man calls Jim and says: “The band wants you to make the new album. Congratulations. You got the job. By the way, I didn’t want you to do it.” Gaines is taken aback but hell, it’s a Texas four-piece blues band, how hard can this really be? “Hard. I was the first person they ever used who wasn’t from the Texas connection,” he says. “It could get tense because I was also the first person to ever tell Stevie: ‘Nope, that’s not good enough. Do it again.’”

On Texas Flood, Couldn’t Stand the Weather and Soul To Soul the band had produced themselves, but while Grammy Awards and critical acclaim ensue, there are many who take the line that Vaughan can’t decide whether to be his heroes Albert King and Jimi Hendrix, or locate his own voice. Modern blues acts are beset by this conundrum – who needs the pastiche when we already got Muddy Waters? But there is a difference: SRV is undoubtedly a genius musician, and when the layers of parody fall away he recalls all the well-known cats, but with a fair measure of the forgotten Lonnie Mack – check him out playing bass on The Doors’ Roadhouse Blues – thrown in for whammy punch.

Gaines and the band decamp to the Power Station in New York City to rehearse, but the producer can’t record a note because there is a god-awful hum in the little room they use that sounds like you’re standing underneath a pylon. Vaughan’s none too happy when Gaines pulls the plug because he’s used this studio before to cut Couldn’t Stand The Weather; it’s also where David Bowie made Let’s Dance, which is smeared all over with Stevie licks and is indeed the album from 1983 that made his name.

“I moved us to Kiva Studios in Memphis and that solved the problem,” says Gaines. “They had a big isolation room and it was great, since the band loved the city and the bosses loved him because he’s a big star. Still had the problem with the amplification though, and I’m known as the man who made him play in a chicken coop. We were getting hum because he’s using a single coil Strat, so I wrapped the room in copper wire to form a conduit and put him inside what looks like a baseball-batting cage. That pulled the interference down 70%. I could live with that.”

Gaines also persuaded the boys they had to embrace the emerging digital technology that enabled him to get round the problem of using eight tracks for one guitar feed. “I was in a panic because pretty soon I’m running out of tracks. We sorted out a 32-track at the Power Station and teamed that with an analogue machine and while everyone then is fearful of digital – Stevie hated it – the tube amps were warm and we didn’t have to use any slaving.”

For the first time SRV and Double Trouble will record without the use of any drink or drugs. Stevie has played with his mentor Bonnie Raitt and discovered that being sober is a blessing for once, and he will go on to deliver some of his finest music since the fucked-up era when he was so majestic on Jennifer Warnes’ classic Leonard Cohen tribute album Famous Blue Raincoat (1987), of which he remembers nothing.

“Considering he almost died in London Stevie was in great shape,” says Jim. “One reason why he chose me was because I’m Mr Squeaky Clean, Mr Hillbilly,” Gaines laughs. “I’ve never done a drug in my life. They were all going through the step programme and attending meetings every night and day. They couldn’t have a drink and smokes man around. Stevie told me: ‘This is the first thing I’ve cut with no chemical enhancement. I’m as nervous as hell.’”

If the days of climbing the walls as withdrawal kicked in were gone, that didn’t mean the sessions were easy. Gaines still had to prove himself to gain entrée in to this tight-knit clan. “I trod with care. I’ve never been a ‘world’s gonna-end’ type and we became friends as the recording progressed. Stevie gave me his trust and laid a lot of his life on me in private moments. I was shocked and privileged to hear that. Stevie told me he wanted to make amends and move forward and In Step and the album he made with brother Jimmie (Family Style) right before he died were his way of removing any bitterness and jealousy from his life and letting it rest.

“When the album was finished he gave me a hug and he wouldn’t let go for minutes. Man, I realised he needed a hug real bad. I learnt a bit about his father, those difficult situations, and I heard how his mother had received that, too. I know how much those boys loved their mom. I treated Stevie and the boys like cousins. I loved ’em, but I couldn’t let them get too much into my life because making an album is business.”

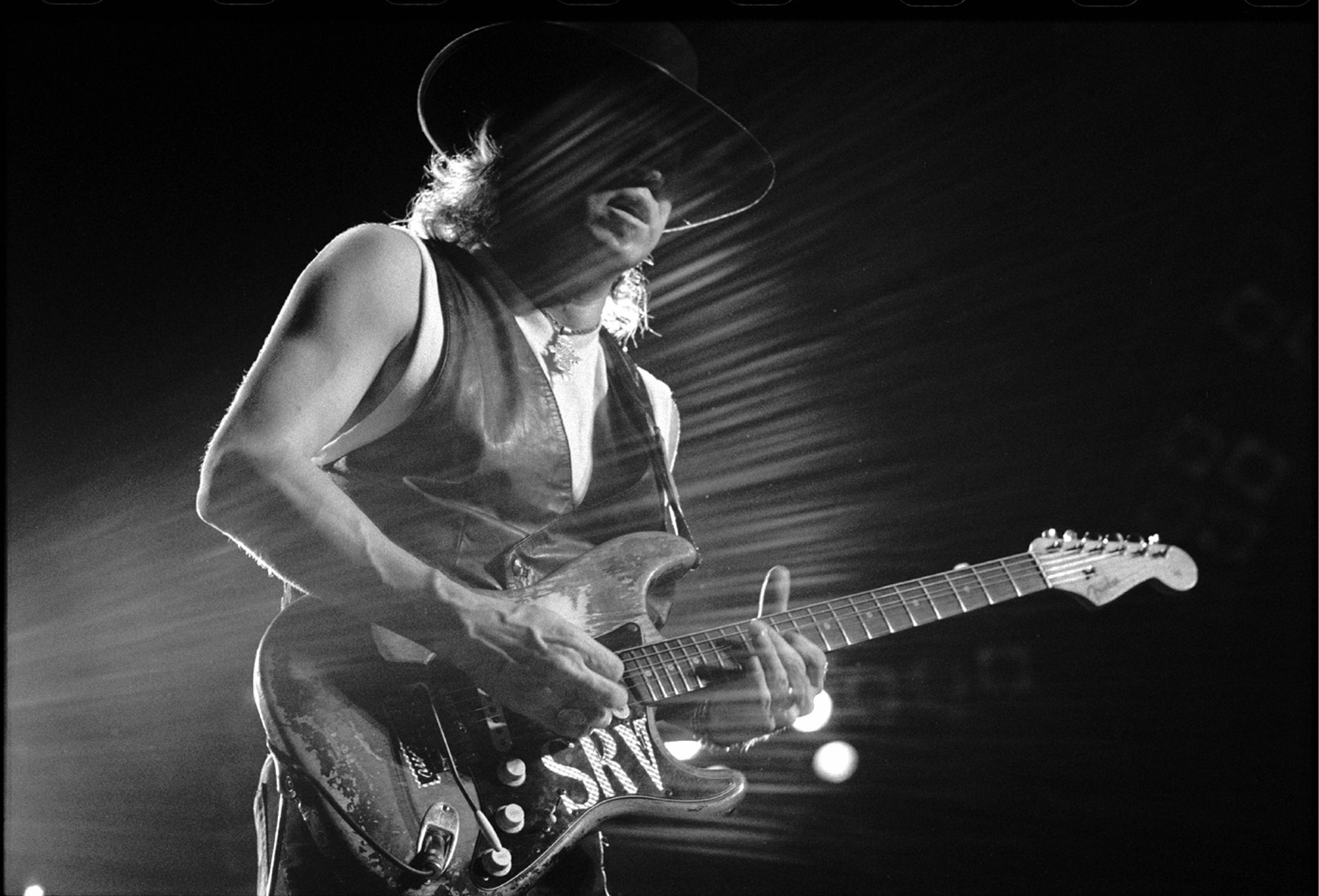

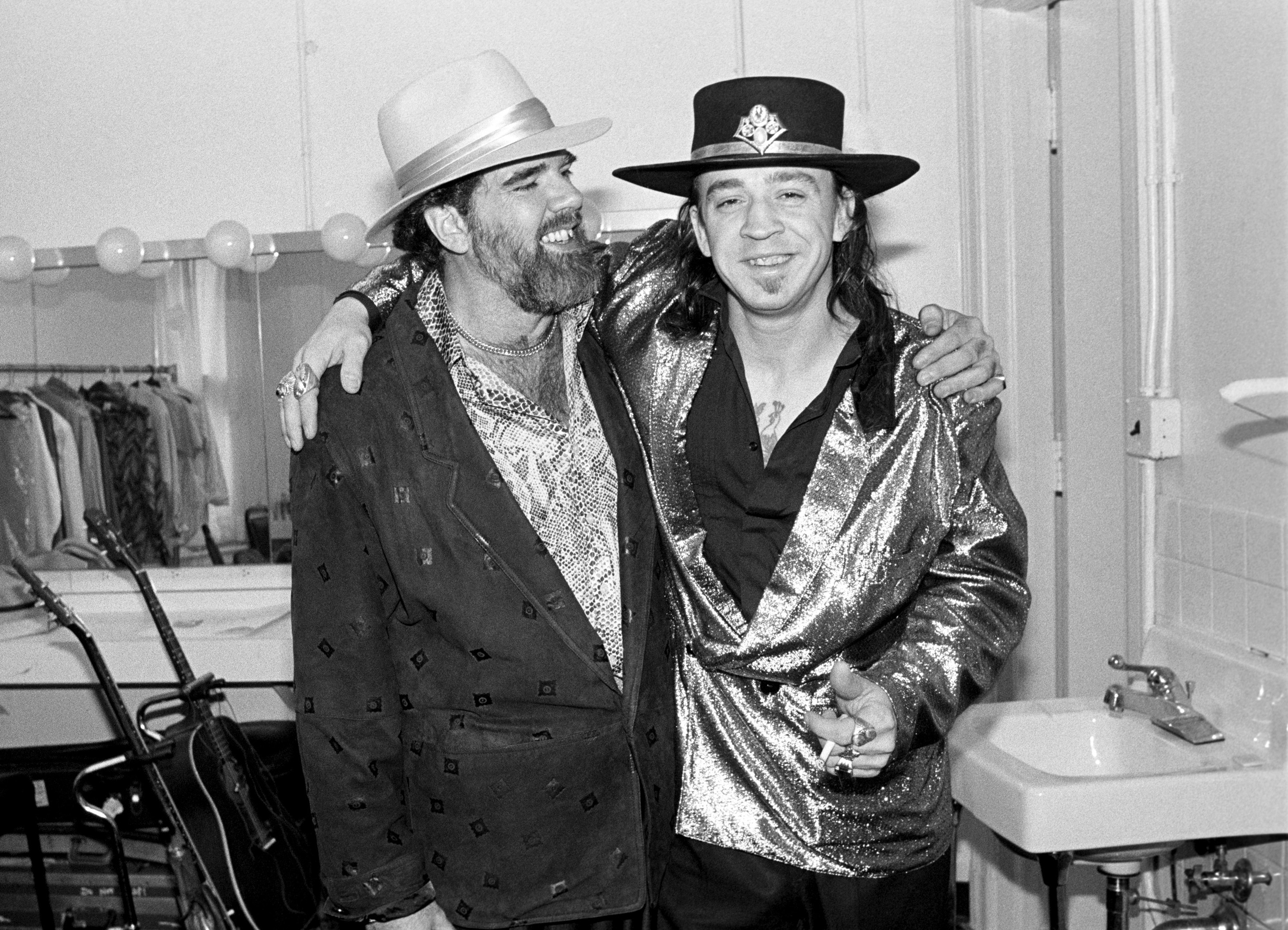

Bro’ Jimmie Vaughan from the Fabulous Thunderbirds hung out during some sessions on In Step, especially when work moved to Los Angeles, and Gaines noticed that maybe the older man was slightly jealous – and certainly in awe of his kid brother, who had achieved such notoriety by playing with Bowie and Nile Rodgers, and especially on Albert King shows, trading white boy licks with AK’s driven Flying V. Stevie was as shy as Jimmie was ebullient. Says Gaines: “He was a small guy but he had very strong hands, and that’s how he could handle those big brass strings he used, especially on the 1959 Fender Strat” (actually a 62⁄63 mongrel SRV called his “first wife” or “Number One”).

The material that became the In Step album impressed the savvy Gaines. It is often described as SRV’s confessional album, but that isn’t the whole truth. Obviously Crossfire, Tightrope and Wall of Denial, with lyrics that refer to being ‘Afraid of my own shadow in the face of grace’ and ‘demons from the garden of white lies’, deal with addiction and redemption, but Stevie didn’t write those words – they were penned by his long-time friend and accomplice, drummer songwriter Doyle Bramhall, who had trodden a similar path and channelled Vaughan’s misery better than he could have done himself. The deeply personal stuff was dispatched first in early January, to get it out the way.

Wrapped around those epic tunes are startling takes on songs by Chester Burnett (Love Me Darlin’), Buddy Guy (Leave My Girl Alone) and Willie Dixon (Let Me Love You Baby) – these situate Vaughan in his natural milieu, less a Hendrix clone and more an old – well 34-year-old – blues man.

In fact Stevie Ray still didn’t feel willing to bare his own lyrical soul, but he made up for that with the gorgeous Travis Walk and the stupendous Riviera Paradise, Gaines’ favourite moment. “I only heard that as a jam in New York, but they had it worked out in Memphis. To set the scene: It was 1am. I turned all the lights way low. Stevie is head down. Tommy and Chris are in the dark. I knew I only had a few minutes of tape on the reel and they start playing, and Holy Shit! It’s magic. As the tape spins it’s so good I have shivers up my spine, but I’m worried we’ll run out. I have to get his attention but he’s got his back to me, so I motion to Chris Layton: ‘CUT CUT’ and then Stevie looks at Chris and they nod. And as the last seconds of tape spool out they end the song and that’s the only take we ever did.”

Gaines finished the album over three months and regards In Step as a success with a proviso. “Stevie hated doing vocals, like really hated that process. I’d have to line him up with Halls cough drops, honey, tea and lemon – anything to get him in the booth. His attitude was: ‘I’m a guitar player who has to sing.’ The other problem I had was when he couldn’t get hold of Janna on the phone. She was in NYC modelling or at the agency or in the apartment she shared with the other girls. They were so young they had a housemother. Stevie would get incredibly nervous if she didn’t pick up. He was so madly in love with her that the sessions would come to a screeching halt and the other guys got pissed off at me! They’d say: ‘Go get him, make him come back’, and I’d say: ‘Dude, he’s in your band, you go and get him.’”

Vaughan also had a tendency to get bored. At those times he’d go into the studio on his own and play Hendrix songs for hours to himself or change the mood with some Buddy Guy or Lonnie Mack tune from his vast repertoire. Gaines would tape some of those moments, surreptitiously, but when he sent the tapes to Epic they got lost, and that infuriates him because: “At those times, you would swear that Hendrix was in the room.”

Sometimes Albert King dropped by or even sat in, which was a problem because he couldn’t be used for contractual reasons and he was apt to throw in some none too helpful comments that had to be politely heard and ignored. But he was also a sweet, somewhat distracted guy. One day a call came through from Jon Bon Jovi asking Stevie – and Albert – if they’d like to guest at the hairy rock god’s LA show. King homes in on this request and asks SRV over the playback: “Hey Stevie. These Jim Bon Jovis: are they pretty big?” Learning, yes they are, King’s eyes lit up, but in the event he didn’t go and chose to go and play cards with a lady friend.

Tenor sax man Joe Sublett and trumpeter Darrell Leonard made their debut as the Texicali Horns on In Step. Gaines wanted them to emulate the Oakland East Bay funk and swagger of his beloved Tower of Power horns, but they stuck to their Texan/Oklahoma blues and shuffles instead. Joe and Darrell were tight together, but Joe had known SRV since 1973 when he was playing alongside the great Marc Benno in The Nightcrawlers, then Paul Ray and the Cobras, and thus to Triple Threat and Double Trouble. They’d been roommates off and on, swapping riffs on Bobby Bland and Ray Charles tunes, or shooting the breeze while listening to King Curtis and David ‘Fathead’ Newman albums, or marvelling at the silky musicianship of Lee Allen and Wes Montgomery.

Sublett was aware that his old colleague had been through major changes in the interim, because SRV’s heavy partying went way back to the mid-70s when he and Bramhall raised it high on the hog in Dallas and Austin.

- Duane Allman: The life and legacy of a southern man

- Interview: Jeff Beck on Hendrix, Page, Clapton, Van Halen and more...

- Stevie Ray Vaughan & Double Trouble: Complete Epic Recordings

- Stevie Ray Vaughan: The Making Of Texas Flood

“I saw In Step as a new birth, although he – all of them – were definitely into the AA book and there was a lot of Christian and higher power talk going on, which comes with that territory,” says Joe now. “I figured Stevie had always had some Christian elements, even in the bad craziness and party all night days he had a spiritual interest. I wasn’t too concerned at the mood in the camp, because even when he hadn’t played at his best he was still great, and now suddenly he was even better. We had a lot of discussions in his car between breaks and he off-loaded. Stevie Ray was very enlightened about playing sober, and very scared.”

Sublett didn’t see him when he’d gone through the terrible stages of his withdrawal – he saw a man who was moving into a kind of Band of Gypsys phase. “Funk meets blues. Maybe with a bit of Kenny Burrell jazz thrown in. Stevie was an ear player; he didn’t read charts. But he could learn a riff in a second and instinctively knew the changes and the octaves – all the little flavours.”

Joe was knocked out by what he saw and heard. He’d played on Soul To Soul in 1985, and seen the other side of Stevie; now it was like regular folks. The horn parts were cut in Los Angeles, but with mutual schedules starting to mount up there was little time to reminisce. Double Trouble were itching to get back on the road long before In Step’s June ’89 release, and the Texicali boys were finishing off an album with Bruce Willis, If It Don’t Kill You, It Just Makes You Stronger, so in the event they cut Crossfire, which became a huge radio hit, and Love Me Darlin’ before they hooked up for some West Coast dates with the Trouble, augmenting their section with David Woodford’s baritone.

“It was fun playing the album tracks live because that record was different sonically; more centred. Before there was this thing of having a guitarist who is incredibly loud but are you hearing the rhythm section? Now you could hear Tommy’s bass and it was better balanced. It was about more than Stevie’s virtuosity, and yet his singing is more confident. That was down to Gaines who was an incredible diplomat, who could tell him: ‘Hey look, let’s hear you sing and back off a bit on the guitar.’ He was worthy of respect, whereas another guy might have been met with: ‘Who the hell are you to tell me with my track record, how I should sound?’ Gaines knew the times were changing and it wasn’t enough just to sound like a blues player on the radio – you had to have something else. And Stevie? I guess he figured, hell I might just learn something to my advantage.”

In the old days Stevie and Joe were like young punks, everything was about the music and the guitar and Stevie would say: “Every time I play a solo, it’s like I’m breakin’ outta jail.” On a personal note Sublett recalls SRV’s “huge hands, like Howlin’ Wolf’s big ol’ paws”, and his pleasant nature. “For years he lived in the house he bought for his mom in Dallas. He never owned any big cars and could care less about possessions. The best thing for him was Janna, because he’d had a lot of turbulence in his marriage. I remember his smile, and if there was a hang up in a session he’d have a goofy grin and say: ‘This too shall pass’.

“He was a hilarious guy really, with a rubber face. He liked pulling stupid expressions. He told me he busted his nose seven or eight times falling out of trees or off cars, but he wasn’t just a simple soul. He was very intelligent. I never saw him as the guy in the hat or the badass guitar slinger or the Spaghetti Western character. He was never a hard-arsed mean guy. His only ego trip was that when he played, he would never want to give you less than 100%. He wasn’t trying to be better than you; he was just trying to be his best. If people told him: ‘Hey man, you’re great,” he’d make a joke out of it.”

While SRV had an image – the hats, the Native American silver, the poncho and soft suede Cheyenne warrior boots, even that was no big deal to him. “He had that look which is what people expected of him and he knew they liked to see him dressing up. But he never took himself so seriously. When I first met him I gave him a flat brown hat, because those Stetsons he wore got so funky.”

Darrell Leonard wasn’t one of the inner circle, but he was impressed with the man from the outset. “As a brass player you think, ‘Oh everyone plays guitar. I’ll just emulate what he does.’ It was harder to do that with him. He didn’t show me any clichés. He didn’t play the obvious. He took the language of the black blues guys and turned it into his voice.”

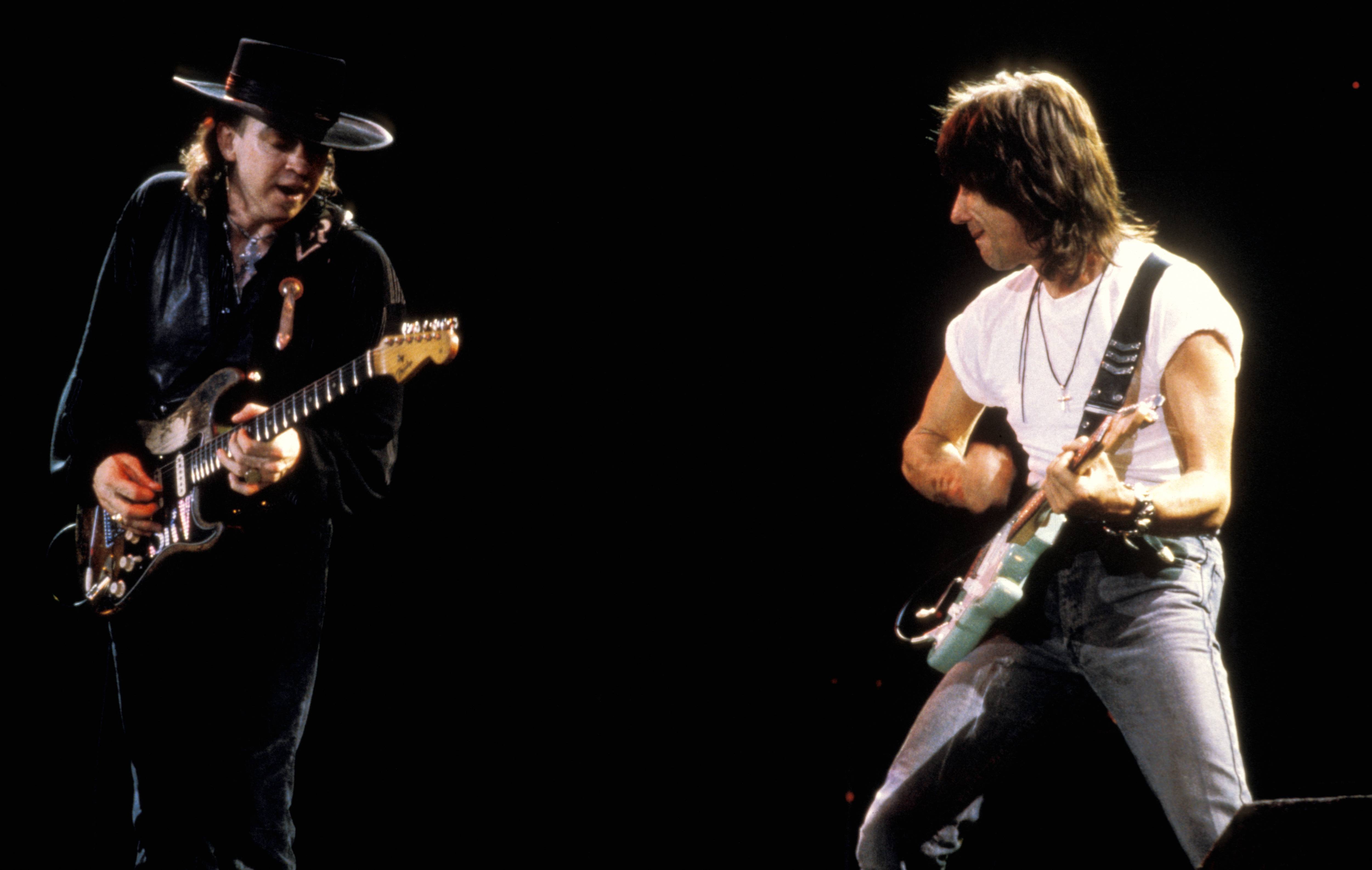

The Texicali boys were overdubbed in LA just before the In Step resumed. In the period after his collapse and before he died Vaughan would play some 300 shows, including The Fire meets The Fury bash with Jeff Beck. Leonard suddenly got the SRV trip. “His connection was all about the audience and letting them know he’d changed. He talked about it directly every night. His thing was: ‘You don’t have be the last person to leave the party.’ He made it a positive. Now there was no party. No pot. No beer. No crazy men out of control with powders and needles. I’d seen all that. Don’t forget Stevie came out of the Austin scene when it was stay up all night. Get high. Repeat. That’s how the blues movement started there. It wasn’t the rinky-dink state capital it is today.”

If Vaughan hadn’t taken that fateful helicopter ride, Leonard believes they’d have worked together again. “He didn’t have any big star vibe. He was regular. I spent one night with him on the bus driving from Northern California to LA for the Greek concert, and he told me about all the shitty stuff. He had hidden depths. But he was cool. I never loaned him money. He never didn’t show up. He was clean and sober. I saw the best SRV possible. I’ve been lucky enough to play with both him and with Duane Allman and I can hear them on the air.”

In early 1990 the Vaughan bothers cut their long-mooted Family Style album that reunited Stevie with Nile Rodgers and some of the cast from Bowie’s Let’s Dance. Rodgers hadn’t wanted him to play on that, telling Bowie: “He’s just an Albert King wannabe.” But Bowie had been knocked out by Double Trouble when they were an unsigned act playing the Montreux jazz festival and told Rodgers: “You’re wrong. He’s a unique artist.”

The producer changed his mind soon afterwards. “He was like a child who was a genius. He was amazed when I sampled his guitar through a Synclavier. ‘What the fuck is that?’ ‘That’s your guitar!’ ‘Holy crap I can play a note and move it from here to here?’ For a person of his virtuosity you never met a more humble person. He wasn’t fake humble. He really was charming and sweet.”

Jimmie Vaughan regarded Family Style as a clean slate for their relationship. “We wanted to do a record that showed everything that we could do on the guitar. The record’s got all of the licks that our favourite guitar players did, plus other stuff. It’s got Albert King, B.B. King, Johnny Watson, T-Bone Walker, Lonnie Mack, Hubert Sumlin and Freddie King. It’s like a short history of who we listened to.”

Yet in many ways it was still like the old days. “One of the first things we cut was Brothers, where we used the same guitar, pulling it out of each other’s hands. People are always asking us questions about what it was like when we were kids, and they probably think that it was just like that, us fighting over the same guitar. So I thought, well, hell, let’s give it to ’em! It was just for fun. And even though it’s the same guitar and the same rig, the tones sound different. The whole project was just fun, and that sort of set the tone.”

Summer of 1990, Double Trouble went on the road with Joe Cocker before their piéce de résistance – two nights with Eric Clapton, Jimmy, Buddy Guy and Robert Cray at Alpine Valley, Wisconsin. After the second show, which climaxed with an encore of Sweet Home Chicago, most of the entourage headed to board four chartered helicopters to take them back to the Windy City and a good night’s rest. Clapton recalls how foggy the early morning of August 27 was.

“I didn’t want to fly at all. I was wiping condensation off the windows and thinking: ‘We’re all gonna die.’” Then they took off and above the weather was clear sky and starlight.”

Vaughan was on a flight with three of Clapton’s crew. In the early hours it was reported they never landed in Chicago. In fact their pilot had taken off and crashed into a ski run on the side of a mountain after 42 seconds. When Jimmie Vaughan went to identify Stevie’s body he had to so by recognising his distinctive silver jewellery.”

Shannon and Layton sat in their hotel room and wept. They’d gone into Stevie’s room hoping he’d be there, but the bed was still made with chocolates on the counterpane and the alarm radio was playing The Eagles’ Peaceful, Easy Feeling.

A strange thing happened at that last gig. Those who knew Stevie said he played with a halo of light around him. His guitar tech Rene Martinez remembered him giving everyone a huge hug and telling them how much he loved them. He had an aura about him, like a premonition.

At Stevie’s funeral the mourners included Stevie Wonder and Dr John, who sang Amazing Grace and Ave Maria while Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, Rodgers, Clapton and ZZ Top wept a Texas flood in the Laurel Land Memorial chapel. Stevie’s marble and bronze headstone simply gave his dates, his name and the inscription that says ‘Thank you… For all the love you passed our way.’

Stevie’s AA speech had spoken of commitment and letting go; of his fears and his desire to help others. He was amazed and grateful to be alive since he’d never believed he’d even make it to 21. His final words to the gathering were heartfelt.

“I thank y’all for letting me be here with you. Whether I know what to say about it or not, it means a lot to me, and I thank you, okay?”

He was back on track. He was in step