It would probably be fair to say that things weren’t looking great for the remaining founder members of Free when the group parted ways in 1973. Their latter years had been marked by discord, much of it prompted by guitarist Paul Kossoff’s worsening addictions and increasing unreliability.

Bassist Andy Fraser had left in disgust the previous year, and there seemed to be little on the horizon for singer Paul Rodgers and drummer Simon Kirke. Yet before the year was out, they would record the first album with a new group that would make them more popular than Free had ever been.

“I was feeling a bit despondent because Free had broken up,” says Kirke. “I met a lady who was Brazilian and she said: ‘Come down and stay with me.’”

He ended up in Brazil for three months. But the itch to hit the drums had not disappeared. A call back home to Rodgers to see if anything was happening led to the discovery that the singer had hitched up with Mick Ralphs, newly departed from his position as guitarist with Mott The Hoople.

Rodgers asked Kirke if he was interested in playing with them. He was.

“When I got back I went over to Paul’s house,” Kirke recalls. “Mick was there, and that was three-quarters of Bad Company.”

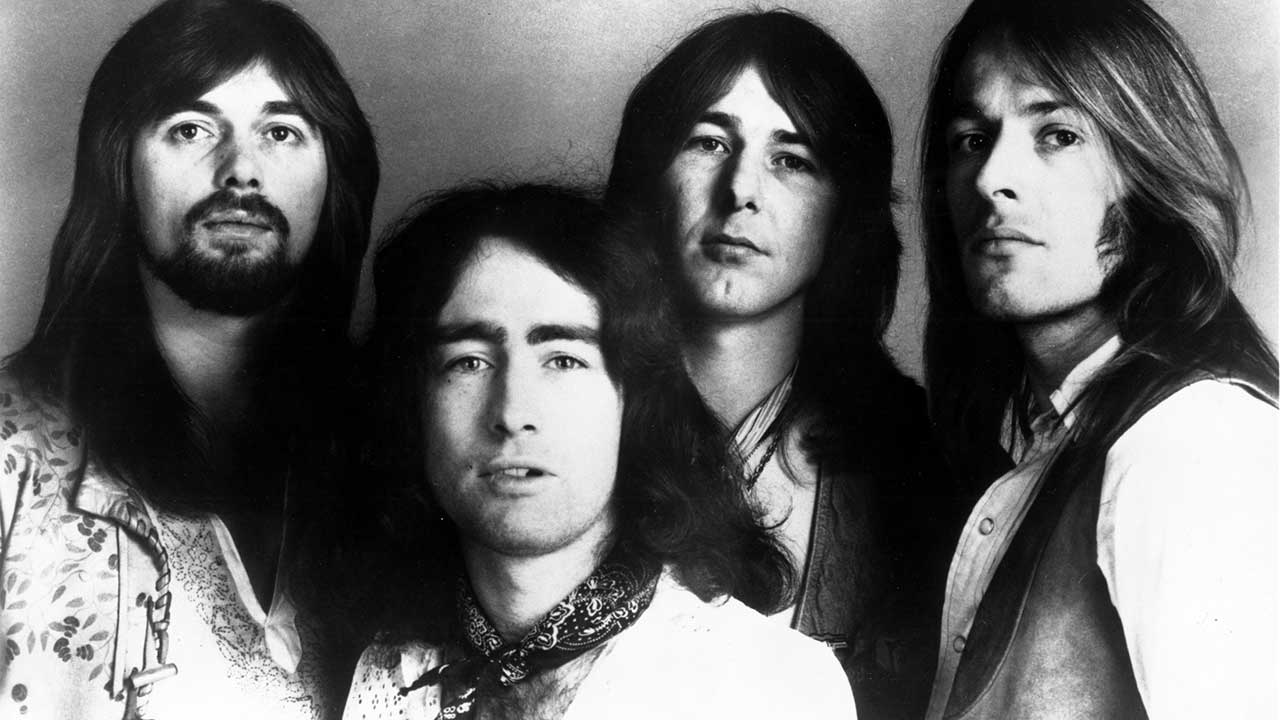

It took some months before they brought in bassist Boz Burrell to complete the line-up. As the band rehearsed, a sound emerged: loose-limbed, spacious and with a bluesy swagger that made their hard rock sound a little less hard than it really was.

Then came the name: it's meaning was either from a Victorian illustration warning of the perils of keeping bad company (according to Rodgers), or because the singer had seen a poster advertising the western Bad Company (according to Kirke). At which point Rodgers decided the band needed a theme tune. It ended up being one of Kirke’s rare writing credits.

“In late 1973 there was a Clint Eastwood western,” Kirke says, naming A Fistful Of Dollars, though he must mean High Plains Drifter, which came out in the second half of that year. “We had this idea about being what they called long riders, who rode across the plains in their long coats, with Winchesters in holsters and tumbleweed blowing across the plain. It was a very romantic image, and Paul was very much enamoured of that picture.”

One day, as Bad Company were working out what they were going to be, Kirke paid a visit to Rodgers’s cottage in Surrey.

“He had this huge Yamaha grand piano which dominated the living room. He was playing in E flat minor, which is quite a hypnotic scale. He had this piano phrase, and the lines ‘Company, always on the run/Destiny is the rising sun/I was born with a six-gun in my hand/Behind the gun I’ll make my final stand.’ That’s all he had.”

It might not have been much, but Kirke was smitten by what he heard. “I thought: ‘Wow.’ It’s not in C major, it’s not in G; it’s not in those everyday chords. I pitched in a line here and there, and we helped each other with the middle eight. I think it was done in about an hour. It was basically a spaghetti western set to music, and it’s been our theme song ever since. I still love playing it to this day, and I’ve played it about 675 times.”

E flat minor is not an easy key for a guitarist, and the group tried moving it to E minor, “but it didn’t have the same soul as in E flat. So Mick was stuck with it.”

The song was both a lament and a celebration, a haunting hymn to the power of the imagination to transport four young Englishmen 100 years back in time, and several thousand miles westward. When the first Bad Company album came out, the song resonated with their audience, too, and was quickly established as a staple of the band’s live show.

But why would people respond so strongly to a song whose meaning was about 19th-century outlaws? After all, send a Bad Company crowd to the old West and it’s highly unlikely than many of them would have been wearing black and rolling revolvers around their index fingers.

Kirke laughs. “Only an Englishman would ask that,” he says. “Most guys are closet outlaws: we wish we could have done this, done that. Certainly when you’re in your early to mid-twenties you could do that – we pushed the envelope now and then. [A pause.] As much as our wives or girlfriends would let us. And there’s something about the outlaw that’s quite romantic.

"Girls like bad guys. They don’t like abusive guys, but they like guys who are a little rough around the edges. So there’s something about being on the wrong side of the law, as long as it’s not too far on the other side of the law, that’s quite appealing to both sexes.”

Given the results when he did set out to write, it’s surprising Kirke didn’t contribute more to Bad Company.

“My songwriting – and I wish it could be a little more tough – has always been a little James Taylorish, a little more ballad-oriented,” he says. “I vent when I play drums – I’m a tough drummer, a hard-hitting drummer. But it tends to rid me of all the nasty attack that hard songs require. I’m a laid-back guy.

"When Mick and Paul took up the reins of songwriting, they did such a good job. I came on board with Weep No More, on the second album. My songs are very melodic, and Paul is a blues singer; he’s not a natural pop singer, and my songs are pop.”

These days, Bad Company’s theme song stirs mixed emotions in Kirke. On the one hand there’s the time-travel element of going back to his youth. On the other there’s the sadness that he will never again get to play it with Ralphs, who had to give up music after a stroke in 2016.

“It will be very strange to go on stage without him,” Kirke says. “I’m getting a bit emotional thinking about it now. But Bad Company’s an amazing band. We’ve been around a long time, and we’re not going anywhere yet."